19 September 2022: Articles

Concurrent Bell’s Palsy and Facial Pain Improving with Multimodal Chiropractic Therapy: A Case Report and Literature Review

Unusual or unexpected effect of treatment, Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Eric Chun-Pu ChuDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.937511

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e937511

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Bell’s palsy, also called facial nerve palsy, occasionally co-occurs with trigeminal neuropathy, which presents as additional facial sensory symptoms and/or neck pain. Bell’s palsy has a proposed viral etiology, in particular when occurring after dental manipulation.

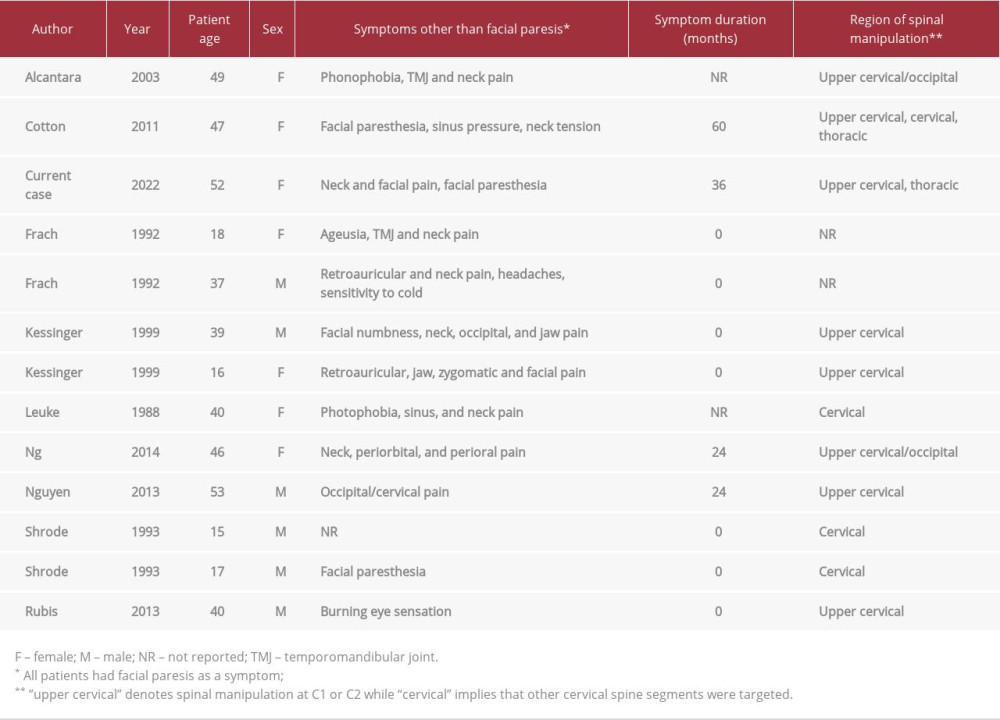

CASE REPORT: A 52-year-old Asian woman presented to a chiropractor with a 3-year history of constant neck pain and left-sided maxillary, eyebrow, and temporomandibular facial pain, paresis, and paresthesia, which began after using a toothpick, causing possible gum trauma. She had previously been treated with antiviral medication and prednisone, Chinese herbal medicine, and acupuncture, but her recovery plateaued at 60% after 1 year. The chiropractor ordered cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging, which demonstrated cervical spondylosis, with no evidence of myelopathy or major pathology. Treatment involved cervical and thoracic spinal manipulation, cervical traction, soft-tissue therapy, and neck exercises. The patient responded positively. At 1-month follow-up, face and neck pain and facial paresis were resolved aside from residual eyelid synkinesis. A literature review identified 12 additional cases in which chiropractic spinal manipulation with multimodal therapies was reported to improve Bell’s palsy. Including the current case, 85% of these patients also had pain in the face or neck.

CONCLUSIONS: This case illustrates improvement of Bell’s palsy and concurrent trigeminal neuropathy with multimodal chiropractic care including spinal manipulation. Limited evidence from other similar cases suggests a role of the trigeminal pathway in these positive treatment responses of Bell’s palsy with concurrent face/neck pain. These findings should be explored with research designs accounting for the natural history of Bell’s palsy.

Keywords: Bell Palsy, Chiropractic, Manipulation, Spinal, Musculoskeletal Manipulations, Neck Pain, Trigeminal Nerve Diseases, Antiviral Agents, Drugs, Chinese Herbal, facial pain, Facial Paralysis, Female, Humans, Middle Aged, Prednisone

Background

Bell’s palsy, also called cranial nerve VII or facial nerve palsy, is a sudden-onset facial weakness with several potential triggers. Co-occurrence of facial nerve palsy with another cranial neuropathy, termed cranial polyneuritis, may be relatively common, with the trigeminal nerve potentially being the most common comorbid cranial neuropathy [1]. While cranial nerve VII is predominantly a motor nerve, co-involvement of the trigeminal nerve, which has a broad sensory distribution, may lead to pain and/or sensory deficits [1–3].

While an overt presentation of trigeminal neuralgia (ie, brief shock-like paroxysmal pain) is rarely reported among those with Bell’s palsy [4], varying degrees of more subtle involvement of the trigeminal pathway in the form of neuropathy may be relatively common. In 1 study, 28% of patients with Bell’s palsy had deficits in trigeminal evoked potentials, suggestive of a dysfunctional trigeminal pathway [2]. In 2 other studies, 25% of patients with Bell’s palsy had evidence of hypoesthesia in the trigeminal distribution [3,5]. In yet another, electro-diagnostic evidence of blink reflex impairment was common among patients with Bell’s palsy, which was suggestive of trigeminal nerve deficits [6].

Bell’s palsy with trigeminal involvement has also been associated with dental procedures [7,8]. It has been suggested that dental manipulation can trigger herpesvirus reactivation, which in turn activates the immune system and can trigger cranial nerve demyelination [7,8]. It has also been proposed that Bell’s palsy patients can develop pain referral to the face, ear, or neck through a central mechanism in which nociceptive signals are transmitted from the facial nerve to the trigeminocervical nucleus in the brainstem [9,10]. While many cases of Bell’s palsy begin to improve within 1 month [11], some are slower to improve, thus patients may seek care from complementary and alternative medical practitioners [4].

The differential diagnosis for facial pain is broad [12,13]. Paroxysmal pain is most suggestive of neuralgia, such as trigeminal neuralgia, although other nerves are rarely involved, such as the supraorbital nerve [12]. When cranial nerve findings are present, such as facial palsy, facial pain is almost always secondary to another condition [12]. Examples include multiple sclerosis and other inflammatory or infectious etiologies such as herpesvirus infections [12]. Facial pain with focal autonomic signs is typically suggestive of trigeminal autonomic cephalgia [12,13]. However, facial pain may also be related to sinus or temporomandibular joint pathology, or be idiopathic [12,13].

In Hong Kong, the setting of the current case, and the United States, chiropractors are portal-of-entry providers that commonly treat neuromusculoskeletal disorders [14–16]. According to a survey conducted in the United States in 2014, chiropractors reported encountering patients with a cranial nerve disorder about 1–6 times per year [17]. In addition, chiropractors often treat patients with neck pain, which can occur in Bell’s palsy, and is the second most common condition chiropractors treat after low back pain [15].

Given that Bell’s palsy can co-occur with symptoms of trigeminal neuropathy such as face and neck pain, and chiropractors may encounter these patients whose symptoms fail to self-resolve, we present an illustrative case of such a patient improving with multimodal chiropractic care including spinal manipulation.

Case Report

PATIENT INFORMATION:

A 52-year-old Asian woman presented to a chiropractor with a 3-year history of constant axial, bilateral, and non-radicular neck pain, and pain, weakness, a subjective sensation of stiffness, and paresthesia of the left side of her face (Figure 1), with pain rated a 4 out of 10 on the numeric rating scale. Symptoms began after cleaning her left maxillary molars with a toothpick, which resulted in an episode of bleeding. Over the span of a few days, her pain and paresthesia spread to the left eyebrow and maxillary and temporomandibular regions (Figure 2), and she also noted the onset of left-sided facial palsy and tinnitus during this period. Her sensory symptoms were constant yet varied depending on activity, with temporomandibular region pain being worsened by talking. She described having an increased sensitivity of left side of her face, with localized tenderness to touch in the region of symptoms. She had no symptoms of dysphonia, dysphagia, or dysarthria and denied having any brief, paroxysmal attacks of facial pain. Her World Health Organization Quality of Life scale (WHOQOL-100) was rated as 72%.

She noted difficulty with drinking water, even with a straw, due to difficulty in grasping the straw with her lips or forming a seal around the edge of a cup, and accordingly could spill liquid when drinking. The patient reported a limited ability to make facial expressions such as smiling due to weakness of the left side of the face and reported a slight drooping of the left eyelid at rest, which was worsened when attempting facial expressions. She also had difficulty with raising the left eyelid and eyebrow, and fully closing the left eye.

The patient denied having any overt infection or fever at the onset of her symptoms but did endorse occasional cold sores around her lips. She denied having any loss of balance, 53-year-old Asian woman presents to chiropractor with a 3-year history of constant neck pain and left facial pain and paresis

Patient’s gums are irritated when cleaning mouth with toothpick; neck pain, face pain and paresthesia, and facial palsy ensue over a few days weakness in the extremities, vision problems, photophobia, hearing problems, cognitive difficulties, loss of taste or smell, pain elsewhere in the head, upper-extremity symptoms, or history of neck or head trauma. She had no history of hyper-tension, diabetes, or seizures, did not smoke or drink alcohol, and was otherwise healthy. The patient denied having a family history of neurological disorders or cancer.

She previously consulted her primary care medical doctor, a dentist, and Chinese medicine practitioner prior to presenting to our office and was diagnosed with Bell’s palsy by all 3 providers. In addition, the dentist diagnosed her with gingivitis, but there was no other significant dental pathology and no sign of caries on dental radiography. She was initially treated by her medical provider with a combination of oral acyclovir and prednisone. The Chinese medicine practitioner then prescribed a combination of herbal medicine (Pueraria 20 g, Ephedra 6 g, Guizhi 10 g, Chinese peony 10 g, silkworm 12 g, white aconite 9 g, whole scorpion 9 g, jujube 6 g, licorice 6 g, ginger 10 g). The patient also received multiple acu-puncture sessions. She had not been recommended botulinum toxin injection.

The patient reported that her symptoms overall had improved by about 60% during the first year of her condition, with the treatments described above, before reaching a plateau. Her symptoms then remained unchanged for 2 years until she presented to the chiropractor. Over-the-counter oral analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs did not provide any relief. The patient was then referred by a family member to the chiropractic office for a second opinion.

CLINICAL FINDINGS:

On physical examination by the chiropractor, the cranial nerve examination was unremarkable, including the corneal reflex, except for the facial paresis. The patient had a drooping of the left eyelid at rest, which was worsened when attempting other facial expressions (ie, synkinesis). She also could not pucker or purse her lips, puff her cheeks, fully close her left eye, fully elevate the left eyebrow, or fully smile on the left side of the face. Given the facial asymmetry at rest and other deficits, the patient was graded IV on the House-Brackmann Facial Paralysis Scale, in which grade VI is total paralysis.

There was no balance abnormality on Romberg’s test, dysdiadochokinesia, intention tremor, or past pointing. Upper-extremity muscle strength and muscle stretch reflexes were normal, and no pathologic reflexes were noted (eg, Babinski sign). The patient noted tenderness with palpation of the left medial eyebrow and maxilla, and the erector spinae were hypertonic bilaterally throughout the cervical spine. There were no physical signs of a functional facial weakness, such as an active contraction of muscles on the lower part of the left side of the face. Further, there were no signs of excessive muscle activity in the left side of the face such, as may be found in blepharospasm or hemifacial spasm.

Motion palpation of the spine revealed restriction with tenderness at the C2–C4 and T2–T5 levels. Her active cervical range of motion was full and pain-free in all directions. While the patient’s neurological examination was unremarkable aside from the facial paresis, her symptoms were atypical enough and had resisted prolonged conservative care; therefore, the chiropractor preferred to order a cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at the initial consultation which was performed on the same day.

The cervical spine MRI revealed low-lying cerebellar tonsils, loss of the cervical lordosis, and degenerative spondylosis (Figure 3). Disc desiccation and mild disc bulges were evident at C2/3, C3/4, C4/5, C5/6, and C6/7, with a posterior annular fissure noted at the C3/4 and C6/7 levels. There was no evidence of myelopathy or other serious pathology on the cervical spine MRI. Accordingly, the chiropractor considered there to be no contraindications to spinal manipulation or other manual therapies directed to the cervical spine.

The patient was placed on a trial schedule of conservative treatment 3 times per week for the first week. All manipulations were performed manually and involved a high-velocity, low-amplitude thrust as part of chiropractic diversified technique [18], and were performed with the use of a cushioned treatment table (Elite, Canada). Manipulations targeted C2 (Figure 4), the upper thoracic segments T2 and T3 (Figure 5), and mid-thoracic segments T4 and T5 (Figure 6), which were levels identified as having hypomobility and tenderness on examination.

Intermittent mechanical cervical traction (Spine MT series, Shinhwa Medical, Korea) was applied for 20-min sessions at each visit. Traction was administered as a means of providing a gentle axial distractive force to alleviate neck pain, relax hypertonic neck muscles, and potentially improve degenerative disc-related symptoms [19]. According to a recent systematic review, cervical spine traction provides a short-term pain-relieving effect [20]. In contrast, spinal manipulation was provided in the regions surrounding these areas of disc degeneration and focused on areas of reduced intervertebral motion and pain on motion palpation.

After the first week of care, the patient reported a reduction in her face and neck pain to a 2/10 on the numeric rating scale, and reported being able to talk without an increase in jaw pain. As the patient had improved, the visit frequency was subsequently reduced to once per week for an additional 3 weeks. Further treatments also included instrument-assisted soft-tissue manipulation (Massage instrument, Strig, Korea) to alleviate hypertonic cervical paraspinal muscles. She was also instructed to perform repeated active cervical retraction exercises in sets of 10, and a gentle upper trapezius stretch (lateral flexion with slight rotation for 10 s, performed bilaterally), each 3 times per day. The patient’s compliance with home exercises was not objectively tracked.

At the 1-month follow-up visit after initial presentation, her WHOQOL-100 score had improved to 98%. Her only residual symptom was mild left eyelid drooping when making other facial expressions (Figure 7). However, her other facial movements were restored. Her face pain, neck pain, and other symptoms were also completely gone. There were no adverse outcomes related to any of the treatments, including spinal manipulation and other therapies. The patient provided written consent for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Discussion

LIMITATIONS:

As an individual case report, our findings may not be broadly generalizable. As the patient had seen several providers over multiple years, some of her previous testing was unavailable or was unclear if it had been conducted altogether, such as brain MRI or viral titers for herpesviruses. Regardless, it did not seem likely that the patient suffered from brain pathology such as a tumor or vascular lesion, given her lack of widespread neurological deficits, limited ability to raise the left eyebrow, which diminishes the likelihood of central nervous system pathology [45], and in retrospect, her rapid response to spinal manipulation. In addition, many of her clinical features and history of cold sore outbreaks were classic for a viral etiology of Bell’s palsy. It is entirely possible that the Bell’s palsy resolved due to natural history. The patient’s response to treatment could have related to a combination of therapies beyond chiropractic spinal manipulation, as cervical traction, soft-tissue treatment, and neck exercises were also implemented. However, these therapies likewise targeted the cervical spine, which we suggest was key to the patient’s improvement.

Conclusions

Patients with Bell’s palsy may also develop symptoms of trigeminal neuropathy. The current case as well as those previously published suggest that these patients may respond to chiropractic multimodal therapy including spinal manipulation, possibly because of the effect of these therapies on the afferents of the trigeminal pathway and accompanying symptoms such as neck pain. Although individual cases show the promise of chiropractic management for these patients, more rigorously designed studies are needed to evaluate the utility of this therapy in Bell’s palsy with or without concurrent trigeminal neuropathy.

Figures

References:

1.. Spector RH, Schwartzman RJ, Benign trigeminal and facial neuropathy: Arch Intern Med, 1975; 135; 992-93

2.. Hanner P, Badr G, Rosenhall U, Edström S, Trigeminal dysfunction in patients with Bell’s palsy: Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh), 1986; 101; 224-30

3.. Benatar M, Edlow J, The spectrum of cranial neuropathy in patients with Bell’s palsy: Arch Intern Med, 2004; 164; 2383-85

4.. Bruton A, Fuller L, Course of concomitant Bell’s palsy and trigeminal neuralgia shortened with a multi-modal intervention: A case report: Explore, 2019; 15; 425-28

5.. Adour KK, Bell DN, Hilsinger RL, Herpes simplex virus in idiopathic facial paralysis (Bell palsy): JAMA, 1975; 233; 527-30

6.. Lee KB, Kim JH, Park YA, Evaluation of trigeminal nerve involvement using blink reflex test in Bell’s palsy: Korean Journal of Audiology, 2011; 15; 129-32

7.. Miles PG, Facial palsy in the dental surgery. Case report and review: Aust Dent J, 1992; 37; 262-65

8.. Gaudin RA, Remenschneider AK, Phillips K, Facial palsy after dental procedures – Is viral reactivation responsible?: J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg, 2017; 45; 71-75

9.. De Seta D, Mancini P, Minni A, Bell’s palsy: Symptoms preceding and accompanying the facial paresis. Sci World J: Hindawi, 2014; 2014; e801971

10.. Han D-G, Pain around the ear in Bell’s palsy is referred pain of facial nerve origin: The role of nervi nervorum: Med Hypotheses, 2010; 74; 235-56

11.. Jowett N, Hadlock TA, Contemporary management of Bell palsy: Facial Plast Surg, 2015; 31; 93-102

12.. Siccoli MM, Bassetti CL, Sándor PS, Facial pain: Clinical differential diagnosis: Lancet Neurol, 2006; 5; 257-67

13.. Zakrzewska J, Differential diagnosis of facial pain and guidelines for management: Br J Anaesth, 2013; 111; 95-104

14.. Leung KY, Chu E: Hong Kong chiropractic survey: Analysis of data, 2021

15.. Beliveau PJH, Wong JJ, Sutton DA, A scoping review of utilization rates, reasons for seeking care, patient profiles, and care provided: Chiropr Man Ther, 2017; 25; 35

16.. Chang M, The chiropractic scope of practice in the United States: A cross-sectional survey: J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 2014; 37; 363-76

17.. Himelfarb I, Hyland J, Ouzts N: National board of chiropractic examiners: Practice analysis of chiropractic 2020 [Internet], 2020, Greeley, CO, NBCE [cited 2020 Nov 7]. Available from: https://www.nbce.org/practice-analysis-of-chiropractic-2020/

18.. Bergmann TF, Peterson DH, Principles of adjustive technique: Chiropr Tech Princ Proced, 2010; 84-142, St. Louis, Mo, Mosby

19.. Graham N, Gross AR, Goldsmith C, Mechanical traction for mechanical neck disorders: A systematic review: J Rehabil Med, 2006; 38; 145-52

20.. Yang J-D, Tam K-W, Huang T-W, Huang , Intermittent cervical traction for treating neck pain: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials: Spine, 2017; 42; 959-65

21.. Chu ECP, Lin AFC, Neck-tongue syndrome: BMJ Case Rep, 2018; 11; e227483

22.. Samim F, Epstein JB, Orofacial neuralgia following whiplash-associated trauma: Case reports and literature review: SN Comprehensive Clininical Medicine, 2019; 1; 627-32

23.. van Dellen JR, Chiari malformation: An unhelpful eponym: World Neurosurg, 2021; 156; 1-3

24.. Peker S, Sirin A, Primary trigeminal neuralgia and the role of pars oralis of the spinal trigeminal nucleus: Med Hypotheses, 2017; 100; 15-18

25.. Das A, Shinde PD, Kesavadas C, Nair M, Teaching neuroimages: Onion-skin pattern facial sensory loss: Neurology, 2011; 77; e45-46

26.. Paulsen F, Waschke J: Sobotta atlas of anatomy: Head, neck and neuro-anatomy, 2019, Elsevier Health Sciences

27.. Ralli M, Greco A, Cialente F, Somatic tinnitus: Int Tinnitus J, 2017; 21; 112-21

28.. Trager RJ, Dusek JA, Chiropractic case reports: A review and bibliometric analysis: Chiropr Man Ther, 2021; 29; 17

29.. Ng SY, Chu MHE, Treatment of Bell’s palsy using monochromatic infrared energy: A report of 2 cases: J Chiropr Med, 2014; 13; 96-103

30.. Rubis LM, Chiropractic management of Bell palsy with low level laser and manipulation: A case report: J Chiropr Med, 2013; 12; 288-91

31.. Cotton BA, Chiropractic care of a 47-year-old woman with chronic Bell’s palsy: A case study: J Chiropr Med, 2011; 10; 288-93

32.. Alcantara J, Plaugher G, Van Wyngarden DL, Chiropractic care of a patient with vertebral subluxation and Bell’s palsy: J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 2003; 26; 253

33.. Shrode LW, Treatment of facial muscles affected by Bell’s palsy with high-voltage electrical muscle stimulation: J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 1993; 16; 347-52

34.. Frach JP, Osterbauer PJ, Fuhr AW, Treatment of Bell’s palsy by mechanical force, manually assisted chiropractic adjusting and high-voltage electro-therapy: J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 1992; 15; 596-98

35.. Leuke CH, Johnson BW, Evaluation of a treatment plan for Bell’s palsy: A case report: Int Rev Chiropr, 1988; 44; 46-47

36.. Kessinger RC, Boneva DV, Vertigo, tinnitus, and hearing loss in the geriatric patient: J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 2000; 23; 352-62

37.. Nguyen AT, Rose K, Hwang S, Integrated chiropractic and acupuncture treatment for a patient with persistent symptoms of Bell’s palsy: A case report: Top Integr Health Care, 2013; 4; 56224933

38.. Hinkeldey N, Okamoto C, Khan J, Spinal manipulation and select manual therapies: Current perspectives: Phys Med Rehabil Clin, 2020; 31; 593-608

39.. Castien R, De Hertogh W, A neuroscience perspective of physical treatment of headache and neck pain: Front Neurol, 2019; 10; 276

40.. Storbeck F, Schlegelmilch K, Streitberger K-J, Delayed recognition of emotional facial expressions in Bell’s palsy: Cortex, 2019; 120; 524-31

41.. Breckenridge JD, Ginn KA, Wallwork SB, McAuley JH, Do people with chronic musculoskeletal pain have impaired motor imagery? A meta-analytical systematic review of the left/right judgment task: J Pain, 2019; 20; 119-32

42.. Haavik H, Kumari N, Holt K, The contemporary model of vertebral column joint dysfunction and impact of high-velocity, low-amplitude controlled vertebral thrusts on neuromuscular function: Eur J Appl Physiol, 2021; 121; 2675-720

43.. McCormick ZL, Burnham T, Cunningham S, Effect of low-dose lido-caine on objective upper extremity strength and immediate pain relief following cervical interlaminar epidural injections: A double-blinded randomized controlled trial: Reg Anesth Pain Med, 2020; 45; 767-73

44.. Zhang R, Wu T, Wang R, Compare the efficacy of acupuncture with drugs in the treatment of Bell’s palsy: Medicine (Baltimore), 2019; 98; e15566

45.. Patel DK, Levin KH, Bell palsy: Clinical examination and management: Cleve Clin J Med, 2015; 82; 419

Figures

In Press

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942032

06 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942937

12 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943244

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943275

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250