07 June 2023: Articles

A Patient with Class III Obesity and a Body Mass Index of 70.1 kg/m Requiring Pulmonary Artery Catheterization to Confirm the Diagnosis of Pulmonary Hypertension

Management of emergency care

Hiroya Hagiwara1ABE, Masayuki AkatsukaDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.939383

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e939383

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Intensive care management of patients with morbid obesity has been linked to a higher mortality rate than that of the normal population and can be challenging. Obesity is a recognized risk factor for pulmonary hypertension, but it can prevent cardiac imaging. This report presents the case of a 28-year-old man with class III (morbid) obesity, a body mass index (BMI) of 70.1 kg/m², and heart failure, requiring pulmonary artery catheterization (PAC) to confirm the diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension.

CASE REPORT: A 28-year-old male patient with a a body mass index (BMI) of 70.1 kg/m² was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for the management of respiratory and cardiac failure. The patient had class III obesity (BMI >50 kg/m²) and heart failure. Due to the difficulties in evaluating hemodynamic status via echocardiography, a pulmonary artery catheter (PAC) was placed, revealing a mean pulmonary artery pressure of 49 mmHg, and a diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension was made. The alveolar partial pressures of oxygen and carbon dioxide were optimized by ventilatory management to reduce pulmonary vascular resistance. The patient was extubated on day 23 and was discharged from the ICU on day 28.

CONCLUSIONS: Pulmonary hypertension should be considered in the evaluation of obese patients. Using a PAC during the intensive care management of a patient with obesity could aid in the diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension as well as cardiac dysfunction, determine treatment strategies, and evaluate hemodynamic responses to various therapies.

Keywords: Catheterization, Swan-Ganz, Heart Failure, Obesity, pulmonary hypertension, Respiratory Insufficiency, Male, Humans, Adult, Hypertension, Pulmonary, Body Mass Index, Obesity, Morbid, Pulmonary Artery

Background

The management of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients with obesity is a clinical challenge for physicians, from diagnosis through to long-term treatment, as patients with obesity have a complex, multifaceted, and progressive prognosis [1].

Obesity and pulmonary hypertension (PH) are known to be closely associated. One study has shown a significant association between subclinical right ventricular dysfunction and increased body mass index (BMI) [2], stating that idiopathic and secondary PHs are associated with obesity. Another study found that the prevalence of secondary PH was 38% in post-menopausal women with obesity [3]. Mechanisms of pulmonary hypertension in obese individuals include: obstructive sleep apnea, obesity hypoventilation syndrome, anorexia, cardiomyopathy, thromboembolism, endothelial dysfunction, and hyperuricemia [4]. Pulmonary hypertension is a potentially life-threatening disease resulting from a variety of pathophysiologic mechanisms, making early diagnosis and treatment necessary. While these findings suggest that obesity can influence PH, data on the prevalence of PH in individuals with obesity are lacking and are mostly from retrospective single-center studies. One study has shown that 5% of healthy subjects with a BMI >30 kg/m2 had moderate to severe PH [5].

Moreover, severely obese patients are prone to developing PH and right-sided heart failure as a result of respiratory acidosis due to obesity hypoventilation syndrome, hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction, and vascular remodeling [4]. Obesity reduces transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) image quality, which can result in the misclassification and misleading assessment of ventricular function, difficult quantification of hemodynamics, and a greater incidence of non-diagnostic studies [6,7]. This report presents the case of a 28-year-old man with class III (morbid) obesity and a body mass index (BMI) of 70.1 kg/m2 requiring pulmonary artery catheterization (PAC) to confirm the diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension.

Case Report

A 28-year-old man with a BMI of 70.1 kg/m2 was admitted to a local hospital after gaining approximately 80 kg in weight during a 1-year period. Moreover, he had worsening edema in both lower legs and dyspnea on exertion 1 week prior to admission. He was transferred to our hospital for the management of respiratory failure complicated by super-obesity. Supplemental oxygen was delivered via a face mask at 3 L/min (FIO2 of 0.3) and an arterial blood gas showed a pH of 7.21, PaCO2 78 mmHg, PaO2 105 mmHg, and HCO3− 30.7 mmol/L. A provisional diagnosis of acute cardiac failure complicated by obesity hypoventilation syndrome was made based on clinical examination, chest X-ray, and an elevated brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) level. The patient was started on noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation therapy and furosemide. On the second day of admission, he developed worsening hypercapnia and impaired consciousness and was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

Results from the physical examination upon admission to the ICU were as follows: GCS 14 (E4V4M6), blood pressure 128/74 mmHg, heart rate 90 bpm, SpO2 90% (spontaneous/timed mode), FIO2 0.45, expiratory positive airway pressure was 6 cmH2O, inspiratory positive airway pressure was 18 cmH2O with a Ti of 2 s and a rise time of 0.3 s. Facial and leg edema were prominent, and he wheezed on expiration. No heart murmur was detected. As he had a short neck, we failed to locate and evaluate the jugular vein.

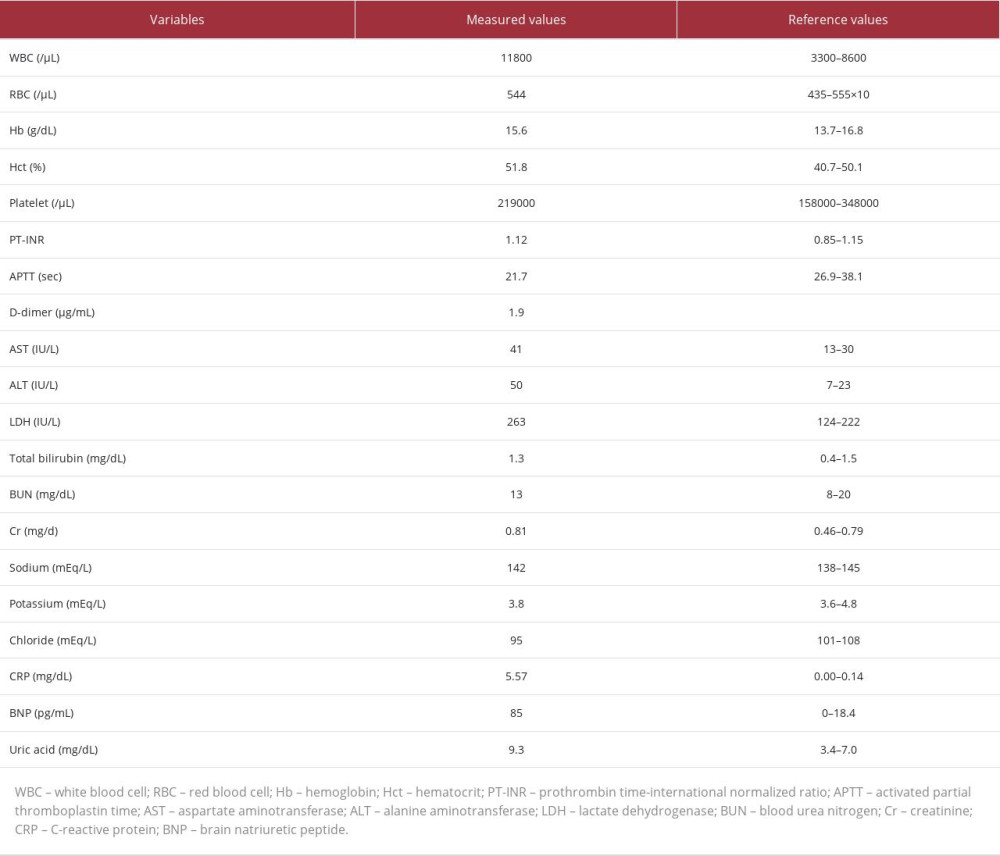

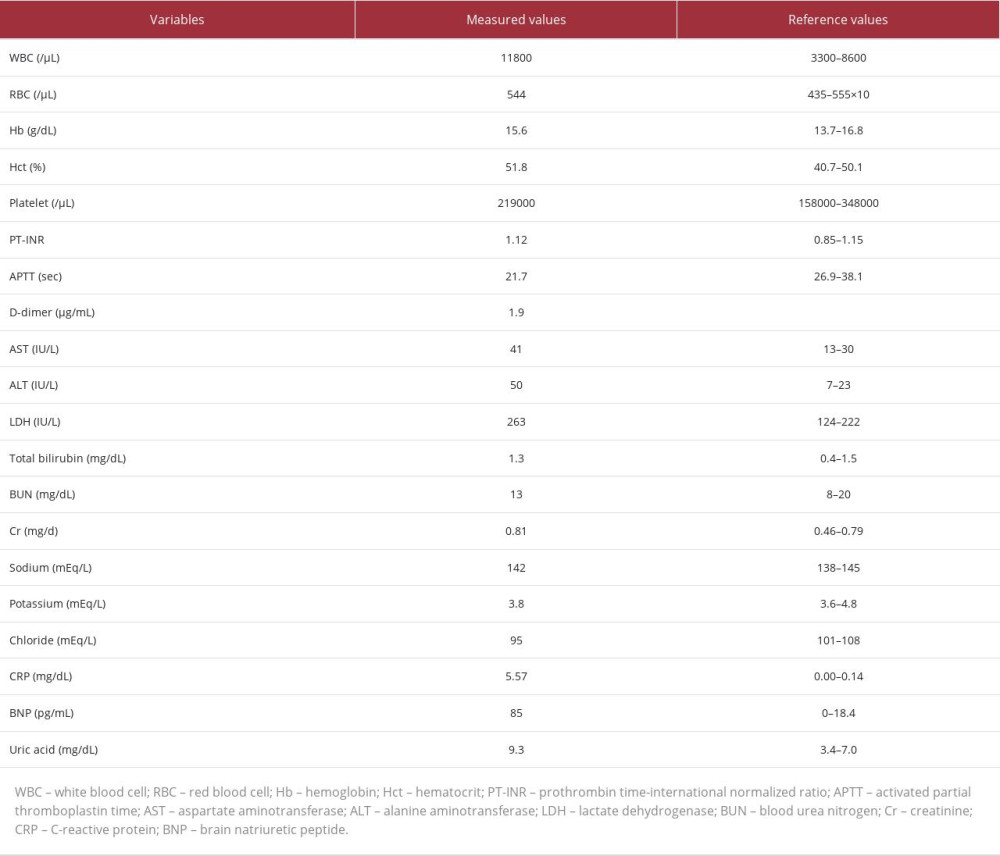

A blood test showed a mildly elevated inflammatory response and BNP level (Table 1). The results of arterial blood gas analysis on ICU admission were pH 7.236, PaCO2 94 mmHg, PaO2 78 mmHg, HCO3 39.1 mmol/L, and lactate 4.9 mmol/L, indicating respiratory acidosis.

A chest radiograph showed marked cardiomegaly (cardiothoracic ratio 66.2%) and enhanced pulmonary vasculature (Figure 1). The electrocardiogram showed a heart rate of 80 bpm with sinus rhythm. Chest computed tomography showed that there was no infiltrative shadow, pleural effusion, or atelectasis (Figure 2A). Contrast-enhanced CT showed no thrombus in the pulmonary artery (Figure 2B).

The patient’s progress after ICU admission is shown in Figure 3. The patient was intubated, and the ventilator was set to assist/control mode, FIO2 0.6, ventilation frequency 16/min, pressure control 16 cmH2O, and positive end-expiratory pressure 10 cmH2O. Since it was difficult to evaluate cardiac function by TTE, a PAC was placed to monitor the hemodynamic status at the bedside with the use of ultrasound [8], revealing a mean pulmonary artery pressure of 49 mmHg, central venous pressure of 10 mmHg, pulmonary artery wedge pressure of 18 mmHg, and cardiac output of 7.8 L/min (cardiac index 2.8 L/min/m2). A diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension was made [9,10]. The alveolar partial pressure of oxygen and carbon dioxide was optimized by ventilatory management to decrease pulmonary vascular resistance. Transoesophageal echocardiography was performed at the bedside on the fifth day. There was no abnormal left ventricular wall motion, significant valvular disease, or patent foramen ovale. During the ventilatory management, positional changes and tracheal aspiration triggered an increase in systolic pulmonary artery pressure to 80–90 mmHg, a decrease in systolic pressure to 60–70 mmHg, and a decrease in SpO2 to <80%. To prevent circulatory collapse caused by reactions to external stimuli, deep sedation management and continuous administration of muscle relaxants were started on the fifth day. On the tenth day, the catheter was removed due to suspicion of catheter infection. The mean pulmonary artery pressure was 31 mmHg. After removal of the PAC, we continued to manage the patient using the rapid decrease in blood pressure and SpO2 as an indicator of a circulatory collapse. Considering septic shock due to catheter infection, noradrenaline (NAd) was continued for hemodynamic maintenance. Conversely, muscle relaxants were discontinued, and spontaneous respiration was restored. The patient’s condition gradually improved, and by the fifteenth day, NAd administration was discontinued because of hemodynamic stability. The patient was extubated on the twenty-third day. He was discharged from the ICU on the twenty-eighth day and was discharged from the hospital based on his request on the eighty-fifth day.

Discussion

In this report, we used a PAC during the intensive care management of a patient with class III obesity, which could aim to make a diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension and cardiac dysfunction, guide treatment decisions, and evaluate the hemodynamic responses to various therapies. The patient’s severe obesity limited our ability to perform TTE. Therefore, PAC implantation was required to monitor the hemodynamics. During the treatment course, the patient had frequent circulatory collapse, which was thought to be related to factors such as increased sympathetic activity caused by positional changes and tracheal suctioning [11], rapid pulmonary vasoconstriction caused by hypoxemia and acidosis [12], and sepsis. Therefore, we decided to induce deep sedation to control the sympathetic nerve stimulation associated with external stimuli. In addition, because transpulmonary pressure is unlikely to cause pulmonary contusion in severely obese patients, even with high intra-airway pressure due to high chest wall elastance, elevated plateau pressure, and driving pressure were tolerated to maintain an adequate ventilation volume. This suggests that a PAC is useful for hemodynamic evaluation of the right heart system.

Various factors contribute to the pathogenesis of PH in severely obese patients. Fat deposition in the neck and thoracic subcutaneous tissue results in decreased thoracic compliance, and increased abdominal visceral fat causes diaphragmatic elevation and narrowing of the upper airways, contributing to decreased ventilation [13]. Respiratory acidosis caused by hypoxemia and hypercarbia associated with alveolar hypoventilation triggers pulmonary vasoconstriction and increases pulmonary arterial pressure. When the upper airway is compressed and obstructed, breathing appears labored, intrathoracic pressure becomes negative, venous perfusion increases and the right heart system becomes capacitively loaded, leading to an increase in pulmonary artery pressure [14]. Moreover, the following causes of PH were identified: genetic mutations, drugs/toxins, congenital heart disease, hypoventilation syndromes, and hematological disorders [9].

Furthermore, at the time of admission, the patient had marked edema throughout the body and cardiac enlargement, suggesting cardiac failure. The patient was then treated for cardiac failure with special attention to fluid management. His weight decreased by 24 kg, allowing him to be weaned off the ventilator.

Regarding the classification of PH, we ruled out pulmonary arterial hypertension because the highest pulmonary artery wedge pressure was 18 mmHg, and we did not conduct a close examination for connective tissue disease or HIV infection. The patient’s rapid weight gain and chronic exposure to hypoxia may have led to PH. This would be classified as PH associated with pulmonary disease and/or hypoxemia (Group 3) [15].

A previous report showed that extracorporeal life support was required to manage the refractory respiratory failure of the patient with obesity and pulmonary hypertension [16]. In our case, PAC was used to identify the patient’s condition early and prevent further progression of respiratory and circulatory failure. As a result, we could avoid the use of extracorporeal life support.

We believe one of the factors that enabled us to manage the PH and cardiac failure in our patient was the placement of the PAC, which allowed us to monitor his hemodynamic status.

Conclusions

Herein, we reported a patient with class III obesity complicated by PH and cardiac failure using a PAC during intensive care management. PH should be considered in the intensive care of patients with severe obesity, and management with a PAC could be useful to monitor hemodynamic status when TTE is not possible.

Figures

References:

1.. Bianchettin RG, Lavie CJ, Lopez-Jimenez F, Challenges in cardiovascular evaluation and management of obese patients: JACC state-of-the-art review: J Am Coll Cardiol, 2023; 81(5); 490-504

2.. Wong CY, O’Moore-Sullivan T, Leano R, Association of subclinical right ventricular dysfunction with obesity: J Am Coll Cardiol, 2006; 47(3); 611-16

3.. Taraseviciute A, Voelkel NF, Severe pulmonary hypertension in postmenopausal obese women: Eur J Med Res, 2006; 11; 198-202

4.. Friedman SE, Andrus BW, Obesity and pulmonary hypertension: A review of pathophysiologic mechanisms: J Obes, 2012; 2012; 505274

5.. McQuillan BM, Picard MH, Leavitt M, Weyman AE, Clinical correlates and reference intervals for pulmonary artery systolic pressure among echocardiographically normal subjects: Circulation, 2001; 104; 2797-802

6.. Singh M, Sethi A, Mishra AK, Echocardiographic imaging challenges in obesity: Guideline recommendations and limitations of adjusting to body size: J Am Heart Assoc, 2020; 9; e014609

7.. Ellenberger K, Jeyaprakash P, Sivapathan S, The effect of obesity on echocardiographic image quality: Heart Lung Circ, 2022; 31; 207-15

8.. Rodriguez Ziccardi M, Khalid N, Pulmonary artery catheterization.: StatPearls [Internet] Aug 29, 2022, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls

9.. Oldroyd SH, Manek G, Sankari A, Bhardwaj A, Pulmonary hypertension. 2022 Nov 3: StatPearls [Internet] Jan, 2022, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing

10.. McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, ACCF/AHA ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association: Developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, Inc., and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association.: Circulation, 2009; 119(16); 2250-94

11.. Hickey PR, Hansen DD, Wessel DL, Blunting of stress responses in the pulmonary circulation of infants by fentanyl.: Anesth Analg, 1985; 64; 1137-42

12.. Rudolph AM, Yuan S, Response of the pulmonary vasculature to hypoxia and H+ ion concentration changes: J Clin Invest, 1966; 45; 399-411

13.. Piper AJ, Grunstein RR, Obesity hypoventilation syndrome: Mechanisms and management: Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2011; 183; 292-98

14.. Friedman SE, Andrus BW, Obesity and pulmonary hypertension: A review of pathophysiologic mechanisms: J Obes, 2012; 2012; 505274

15.. Simonneau G, Gatzoulis MA, Adatia I, Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension: J Am Coll Cardiol, 2013; 62; D34-D41

16.. Park MH, Lee MJ, Kim JS, Veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation rescue for pulmonary hypertension and hypoxemic respiratory failure to obesity hypoventilation syndrome: a case report: Ann Palliat Med, 2022; 11(10); 3341-45

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Blood test on ICU admission. There was a mild elevation of WBC, CRP, BNP, and uric acid. There were no significant abnormalities in other variables.

Table 1.. Blood test on ICU admission. There was a mild elevation of WBC, CRP, BNP, and uric acid. There were no significant abnormalities in other variables. Table 1.. Blood test on ICU admission. There was a mild elevation of WBC, CRP, BNP, and uric acid. There were no significant abnormalities in other variables.

Table 1.. Blood test on ICU admission. There was a mild elevation of WBC, CRP, BNP, and uric acid. There were no significant abnormalities in other variables. In Press

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942770

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943214

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943010

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943687

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250