29 May 2023: Articles

A Rare Case of Primary Adrenal Epithelioid Angiosarcoma

Challenging differential diagnosis, Rare disease, Educational Purpose (only if useful for a systematic review or synthesis)

Komson WannasaiDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.939397

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e939397

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Primary adrenal epithelioid angiosarcoma (PAEA) is a very uncommon primary adrenal gland tumor that usually occurs around the age of 60 years and is more common among males. Owing to its rarity and histopathological features, PAEA could be misdiagnosed as adrenal cortical adenoma, adrenal cortical carcinoma, or other metastatic cancers, such as metastatic malignant melanoma and epithelioid hemangioendothelioma.

CASE REPORT: A 59-year-old male patient presented to our hospital with a complaint of abdominal bloating that started 2 months prior. His vital signs and the results of his physical and neurological examinations were unremarkable. A computed tomography scan showed a lobulated mass arising from the hepatic limb of the right adrenal gland but no evidence of metastasis to the chest or abdomen. The patient underwent right adrenalectomy, and the macroscopic pathological findings from a right adrenalectomy specimen revealed atypical tumor cells with an epithelioid appearance in the background of an adrenal cortical adenoma. Immunohistochemical staining was performed to confirm the diagnosis. The final diagnosis was epithelioid angiosarcoma involving the right adrenal gland with a background adrenal cortical adenoma. The patient had no postoperative complications, pain in the surgical wound, or fever. Therefore, he was discharged with a schedule for followup appointments.

CONCLUSIONS: PAEA may be misinterpreted as adrenal cortical carcinoma, metastatic carcinoma, or malignant melanoma radiologically and histologically. Immunohistochemical stains are essential for diagnosing PAEA. Surgery and strict monitoring are the main treatments. In addition, early diagnosis is essential for patient recovery.

Keywords: Adrenal Gland Diseases, Sarcoma, case reports, Abdominal Neoplasms, Abdominal Pain, Male, Humans, Middle Aged, Adrenocortical Adenoma, adrenocortical carcinoma, Hemangioendothelioma, Epithelioid, Hemangiosarcoma, Adrenal Gland Neoplasms, Melanoma, Adrenal Cortex Neoplasms

Background

Angiosarcoma is a rare tumor that accounts for less than 2% of all sarcomas [1]. It is typically found in the skin, head and neck, extremities, peritoneum, body wall, retroperitoneal area, breast, liver, spleen, heart, lung, bone, or adrenal glands [2,3], and rarely in the gastrointestinal tract, urinary bladder, penis, or testes [4]. Angiosarcomas can be subdivided into a number of subtypes based on differentiation. These subtypes range from well-differentiated tumors with numerous vascular channels to poorly differentiated tumors with solid sheets and no vascular formations [5]. Additionally, angiosarcomas can be subdivided based on the histopathology of the tumor cells, such as spindle, polygonal, epithelioid, round, or solid sheets [1].

Primary adrenal epithelioid angiosarcoma (PAEA) is an extremely rare primary adrenal gland tumor that typically occurs around the age of 60 years and is more common in men [6]. The tumor is composed of sheets of pleomorphic, atypical, endothelial cells that exhibit an epithelioid morphology [7]. Owing to its rarity and histopathological characteristics, PAEA may be misdiagnosed as adrenal cortical adenoma, adrenal cortical carcinoma, or other metastatic tumors, including metastatic malignant melanoma and epithelioid hemangioendothelioma [8], and can be diagnostically challenging with regard to both radiologic and pathologic findings. Herein, we report a case of PAEA diagnosed at our hospital and review previously reported cases of PAEA with a discussion on radiologic and pathologic findings with possible differential diagnoses to facilitate accurate diagnosis of the disease.

Case Report

A 59-year-old male patient presented to our hospital with a complaint of abdominal bloating that started 2 months prior. He reported that the severity of his symptoms increased after eating, particularly after eating fatty foods, and that he experienced intermittent pain on the right side of his abdomen. The patient reported that he had no diarrhea, anorexia, weight loss, fever, palpitations, or headaches. However, he had a 30-year history of alcohol consumption and smoking, both of which he had quit 1 year prior to his visit. On physical examination, the patient was fully conscious, cooperative, and oriented. His vital signs were unremarkable. The patient did not have pale conjunctivae, icteric sclerae, an irregular heartbeat, heart murmurs, or abnormal respiration, and except for a right intra-abdominal mass, there was no evidence of hepatosplenomegaly. The results of his neurological examination were unremarkable.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the patient’s abdomen (Figure 1) showed an 8.7×7.5×6.3 cm lobulated mass arising from the right adrenal gland. The tumor compressed the surrounding right lobe of the liver, right kidney, and inferior vena cava without any apparent invasion. No evidence of metastasis to the chest or abdomen was detected. Several punctate calcifications were visible. On contrast-enhanced images, there were a few peripheral arterial enhancing foci with progressive enhancement in later-phase images. However, inhomogeneous enhancement persisted, representing necrosis. As these CT findings were not indicative of a specific tumor, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed.

MRI (Figure 2) revealed that the mass was heterogeneously enhanced, with non-enhanced areas of necrosis, similar to those observed on CT. Additionally, MRI revealed T1-hyperintense regions in fat-suppressed images, indicating intra-tumoral hemorrhages. A small area of intracytoplasmic fat was observed as T1-signal drop on the opposed-phase T1-weighted image. However, no gross fat component was detected on MRI or CT images. Despite the indeterminate nature of the mass as revealed by the MRI, imaging exhibited a notable absence of vascular invasion, lymphadenopathy, or distant metastases, thereby implying the likelihood of surgical resectability.

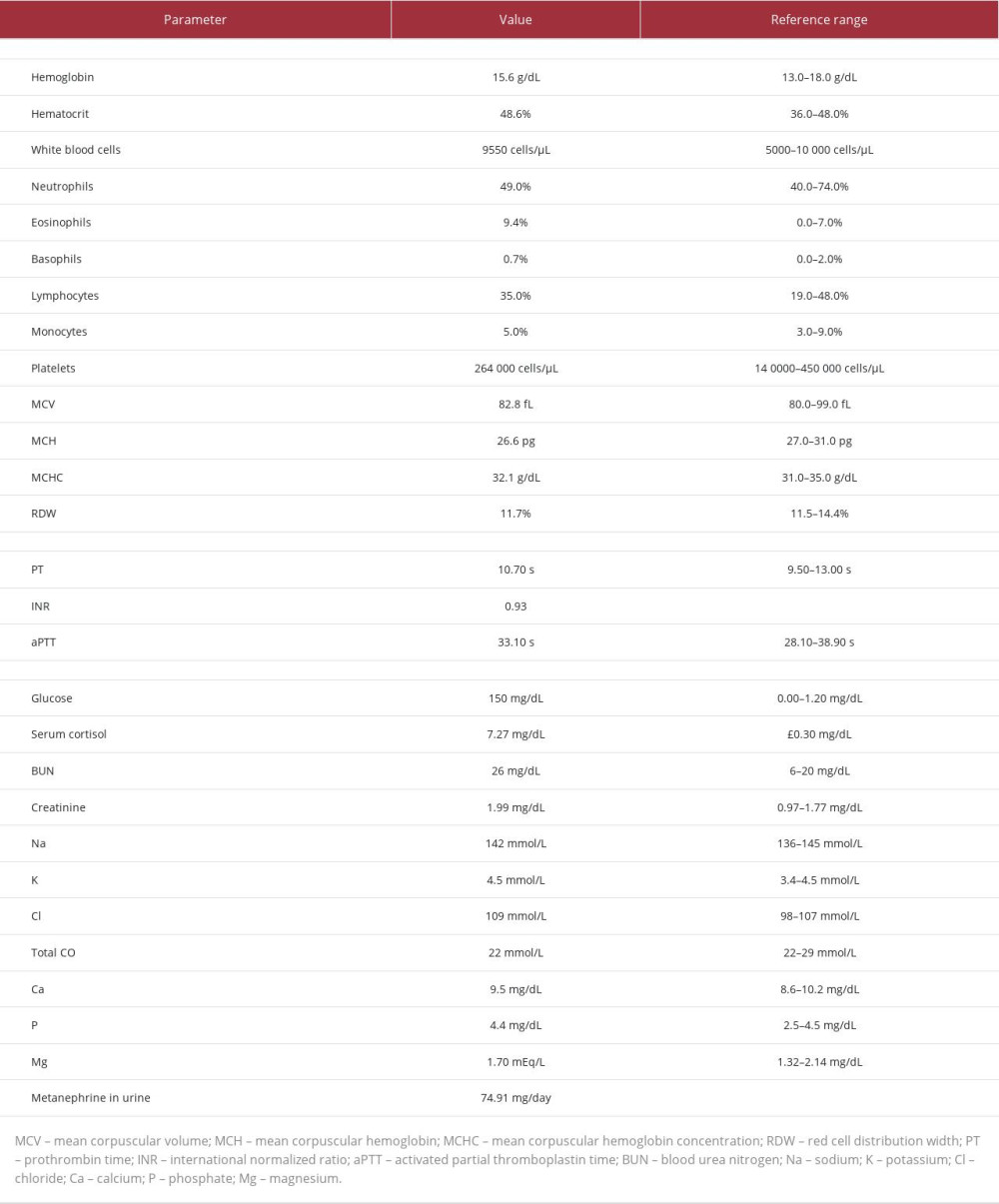

Preoperative laboratory analysis (Table 1) revealed eosinophilia with no anemia and normal blood electrolyte levels and renal function. The metanephrine and vanillylmandelic acid levels in the patient’s urine were unremarkable.

The patient underwent right adrenalectomy. The gross specimen (Figure 3) revealed the presence of a well-circumscribed encapsulated adrenal tumor measuring 8.5×6×6.5 cm. Cut surfaces of the tumor showed 3 yellow-tan nodules with hemorrhagic areas. On microscopic examination (Figure 4), the tumor demonstrated anastomosing vascular channels with atypical neoplastic cells in the background of an adrenal cortical adenoma. The tumor cells were characterized by large, atypical epithelioid appearance with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. The mitotic count was 7/10 high-power fields. Immunohistochemistry showed that the tumor cells were strongly positive for CD31 (Figure 5), CD34, and Factor VIII but only partially positive for cytokeratin (CK) (Figure 5). These features suggested a vascular origin of the tumor cells. To confirm the diagnosis of angiosarcoma, immunohistochemical staining for FLI1 and INI1 was performed, which showed positive results (Figure 5). However, we needed to exclude other malignant tumors, such as adrenal cortical carcinoma, metastatic malignant melanoma, neuroendocrine tumor, or germ cell tumor. Thus, additional immunohistochemical stains for inhibin, calretinin, melan-A, synaptophysin, S-100, and HMB45 were performed. All the stains returned negative results. The final diagnosis was epithelioid angiosarcoma involving the right adrenal gland with a background adrenal cortical adenoma. The surgical margins of the specimen were free of malignancy.

The patient had no postoperative complications, pain in the surgical wound, or fever. In a multidisciplinary team conference, the oncologist decided against chemotherapy or radiotherapy owing to complete (R0) resection of the tumor. Thus, the patient was discharged by the surgeon with a followup appointment for imaging 4 months from discharge. Unfortunately, the patient did not visit for a postoperative examination and was eventually lost to followup.

Discussion

We report a 59-year-old male patient who presented with abdominal bloating. Radiologic examinations revealed a right adrenal mass. A diagnosis of PAEA was made according to pathologic findings.

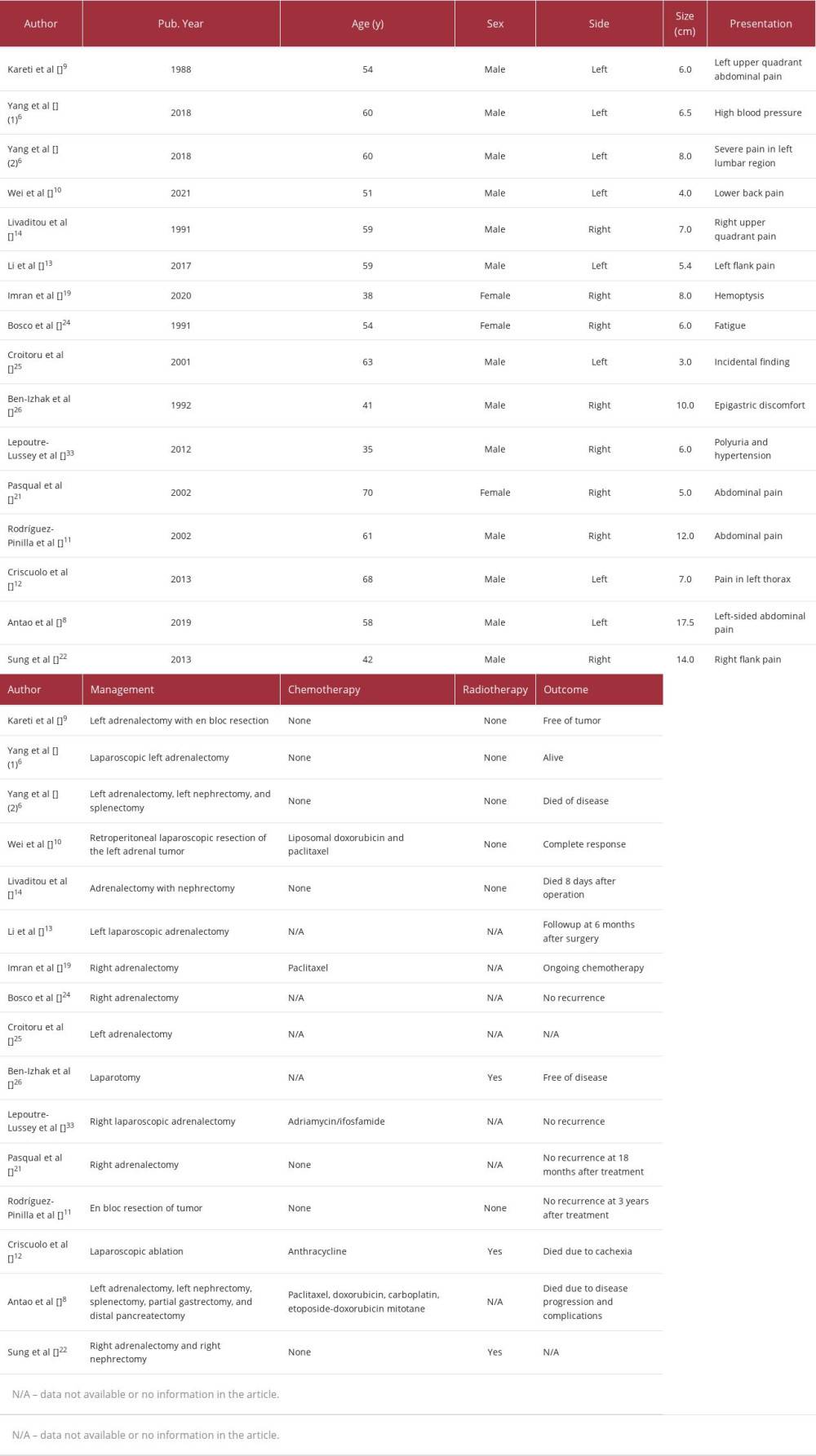

PAEA is a very rare malignant vascular tumor of the adrenal gland [6]. In 1988, Kareti et al [9] first described PAEA in a 54-year-old male patient who presented with abdominal pain and a left adrenal mass. Although the tumor – showing characteristics of an epithelioid angiosarcoma – was surgically removed, the patient experienced recurrence and died 7 months after surgery. In 2018, Yang et al [6] reviewed 37 cases of PAEA, including the case reported by Kareti et al, while Wei et al [10] reported 1 case of PAEA in 2021.

The cause of PAEA remains unknown [11]. However, it has been reported that PAEA is linked to exposure to insecticides containing arsenic [12]. PAEA may also be found in patients with a history of vinyl chloride exposure [13]. Livaditou et al [14] described a 59-year-old male patient who presented with abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant and had a history of exposure to an insecticide containing arsenic, for over 20 years. A mass was detected in the upper pole of the kidney, and pathological examination confirmed that it was an epithelioid angiosarcoma.

Patients with PAEA typically present with an adrenal mass and non-specific symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, and fatigue. However, some patients may be asymptomatic and the tumor may be discovered incidentally through imaging [8].

As PAEA is uncommon and has histopathological characteristics similar to those of many other types of tumors, including adrenal carcinoma, metastatic carcinoma, malignant melanoma, and other types of tumors with epithelioid morphology characteristics, its diagnosis is challenging. However, imaging and pathological studies with immunohistochemical staining can aid in the accurate diagnosis of the disease [6].

Given that CT and MRI of PAEA reveal peripheral hypervascularity with intratumoral hemorrhages, necroses, scant punctate calcifications, and minute intracytoplasmic fat, its differential diagnoses include benign or malignant pheochromocytoma, cortical carcinoma, bleeding adenoma, bleeding hemangioma, metastasis, and mesenchymal tumors such as sarcomas or neurogenic tumors, as well as collision, which have been reported to show heterogeneous enhancement with possible calcifications [15–17]. The clinical manifestations and laboratory findings of PAEA are usually benign. Imaging cannot be used to precisely diagnose the mass; therefore, surgical resection and histopathological analysis are required. However, in surgical planning, the size of the adrenal mass obtained from imaging can be used as another essential factor [16,17].

Some previous case reports indicate that the imaging findings of adrenal angiosarcoma include a circumscribed mass with T1-hyperintensity, which is likely an intratumoral hemorrhage, punctate calcifications, heterogeneous enhancement, and delayed enhancement [18–21]. However, a greater proportion of cystic components in adrenal angiosarcoma has been reported in other case reports [22,23]. Considering the present case and previous reports, adrenal lesions with these characteristics have numerous differential diagnoses; thus, their diagnosis is inconclusive. The purpose of imaging is to determine the resectability of the tumor and search for other indicators, such as intratumoral fat or a primary tumor that has spread to the adrenal gland. Surgical resection and histopathological examination are required in the absence of other indicators.

Bosco et al [24] described a case of PAEA in the right adrenal gland of a 54-year-old patient and reported that the tumor cells tested positive for factor VIII and cytokeratin. In another case of PAEA in the right adrenal gland of a 63-year-old patient reported by Croitoru et al [25], the tumor cells tested positive for CD34, vimentin, and factor VIII but negative for S-100, chromogranin, HMB 45, and CAM 5.2. Ben-Izhak et al [26] also reported positive results for FVIII-RA, UEA-I, vimentin, CAM 5.2, and broad-spectrum CK in the cells of a PAEA in a male patient aged 41 years.

In the present case, the differential diagnoses included adrenal cortical carcinoma, metastatic carcinoma, and metastatic melanoma because the tumor cells exhibited characteristics similar to those of these tumors, such as enlarged nuclei, distinct nucleoli, a high N/C ratio, and abundant cytoplasm. Therefore, immunohistochemical staining was necessary to aid in accurate diagnosis. The stains returned positive results for cytokeratin and negative results for inhibin, calretinin, melan-A, HMB45, synaptophysin, and S-100. The negative results for calretinin, inhibin, and melan-A indicated that the tumor cells did not originate from the adrenal cortex or exhibit adrenal cortical differentiation [6,27]. Additionally, the negative results for HMB-45 and S-100 excluded metastatic melanoma. We performed additional immunohistochemical staining for endothelial markers (CD31, CD34, and factor VIII), FLI-1, and INI1. The results revealed that the tumor cells were positive for all 3 endothelial markers, exhibited a focally positive effect on FLI-1, and expressed INI1. The fact that the tumor cells expressed CD31, CD34, and factor VIII indicated that endothelial cells were indeed the source of the tumor cells [28] and that metastatic carcinoma could be ruled out since carcinomas are negative for endothelial markers [1]. Additionally, the fact that the tumor cells expressed FLI1 and INI1 confirmed that the tumor was an epithelioid angiosarcoma [29,30].

PAEA is a malignant and aggressive tumor with a poor prognosis. The 5-year survival rate for patients with PAEA ranges from 24% to 31% [31]. Wenig et al [32], who studied 9 patients with PAEA, revealed that 3 patients had disease-free stages for 6, 11, and 13 years following surgery. Two patients died of unrelated causes 2 and 4 months after surgery; they had not experienced any recurrence. Another patient was diagnosed with a diffuse spread of the disease in the abdomen 6 months after the surgery. Extensive surgery to remove the metastatic lesions was performed and chemotherapy was administered but the patient died of unidentified causes with no evidence of tumors. Three of the patients with metastatic adrenal epithelioid angiosarcoma died.

Recovery from PAEA has been reported in some cases. In the report by Bosco et al [24], the patient showed symptoms of paraneoplastic syndrome (anemia, fever, cough, and headache); however, no tumor recurrence was detected after surgery. In the report by Ben-Izhak et al [26], a patient with PAEA of the right adrenal gland reported anemia and abdominal pain 2 weeks after surgery due to hematoma and a residual tumor. However, the patient underwent a second operation and radiation therapy, and was subsequently cured.

There are currently no clear treatment guidelines for PAEA [6]. In addition, the positive effects of chemotherapy on PAEA are still debated [6]. The chemotherapy agents, adriamycin and ifosfamide, were administered to a patient with PAEA in a previously reported case [33]. The patient responded well to treatment and exhibited no recurrence. In a study by Cornejo et al [34], 4 patients underwent surgery for tumor removal but did not receive chemotherapy. Two of them died from recurrence at 5 and 16 months after surgery, one showed recurrence of the disease but was still alive 19 months after surgery, and one was cured of the disease. Regarding the patient in the present case, the treatment consisted of surgical removal of the tumor, with recommended followup examinations 4 months later. Table 2 summarizes the cases of PAEA published in the literature with essential information including that of chemoradiation therapy and outcomes of the patients.

Conclusions

We report a case of PAEA arising from an adrenal cortical adenoma with a favorable clinical course. PAEA may be misdiagnosed radiologically and histologically as adrenal cortical carcinoma, metastatic carcinoma, or malignant melanoma. Immunohistochemical stains play a crucial role in establishing a definitive diagnosis of PAEA. Surgical removal of the tumor is the primary treatment, followed by close monitoring. However, early detection of the tumor is crucial for the patient’s recovery.

Figures

References:

1.. Cao J, Wang J, He C, Fang M, Angiosarcoma: A review of diagnosis and current treatment: Am J Cancer Res, 2019; 9; 2303-13

2.. Young RJ, Brown NJ, Reed MW, Angiosarcoma: Lancet Oncol, 2010; 11; 983-91

3.. Khan JA, Maki RG, Ravi V, Pathologic angiogenesis of malignant vascular sarcomas: Implications for treatment: J Clin Oncol, 2018; 36; 194-201

4.. Gaballah AH, Jensen CT, Palmquist S, Angiosarcoma: Clinical and imaging features from head to toe: Br J Radiol, 2017; 90; 20170039

5.. Fomete B, Samaila M, Edaigbini S, Primary oral soft tissue angiosarcoma of the cheek: A case report and literature review: J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg, 2015; 41; 273-77

6.. Yang F, Yang Y, Yu J, Primary epithelioid angiosarcoma of the adrenal gland: Aggressive histological features and clinical behavior: Int J Clin Exp Pathol, 2018; 11; 2721-27

7.. Lang J, Chen L, Chen B, Epithelioid angiosarcoma of the spine: A case report of a rare bone tumor: Oncol Lett, 2014; 7; 2170-74

8.. Antao N, Ogawa M, Ahmed Z, Adrenal angiosarcoma: A diagnostic dilemma: Cureus, 2019; 11; e5370

9.. Kareti LR, Katlein S, Siew S, Blauvelt A, Angiosarcoma of the adrenal gland: Arch Pathol Lab Med, 1988; 112; 1163-65

10.. Wei H, Mao J, Wu Y, Zhou Q, Case report: Postoperative recurrence of adrenal epithelioid angiosarcoma achieved complete response by combination chemotherapy with liposomal doxorubicin and paclitaxel: Front Oncol, 2021; 11; 791121

11.. Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Benito-Berlinches A, Ballestin C, Usera G, Angiosarcoma of adrenal gland report of a case and review of the literature: Rev Esp Patol, 2002; 35(2); 227-32

12.. Ladenheim A, Tian M, Afify A, Primary angiosarcoma of the adrenal gland: Report of 2 cases and review of the literature: Int J Surg Pathol, 2022; 30(1); 76-85

13.. Criscuolo M, Valerio J, Gianicolo ME, A vinyl chloride-exposed worker with an adrenal gland angiosarcoma: A case report: Ind Health, 2014; 52; 66-70

14.. Livaditou A, Alexiou G, Floros D, Epithelioid angiosarcoma of the adrenal gland associated with chronic arsenical intoxication?: Pathol Res Pract, 1991; 187; 284-89

15.. Albano D, Agnello F, Midiri F, Imaging features of adrenal masses: Insights Imaging, 2019; 10; 1

16.. Mayo-Smith WW, Boland GW, Noto RB, Lee MJ, State-of-the-art adrenal imaging: Radiographics, 2001; 21; 995-1012

17.. Guerrisi A, Marin D, Baski M, Adrenal lesions: Spectrum of imaging findings with emphasis on multi-detector computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging: J Clin Imaging Sci, 2013; 3; 61

18.. Li XM, Yang H, Reng J, A case report of primary adrenal angiosarcoma as depicted on magnetic resonance imaging: Medicine (Baltimore), 2017; 96; e8551

19.. Imran S, Allen A, Saeed DM, Adrenal angiosarcoma with metastasis: Imaging and histopathology of a rare adrenal cancer: Radiol Case Rep, 2020; 15; 460-66

20.. Fuletra JG, Ristau BT, Milestone B, Angiosarcoma of the adrenal gland treated using a multimodal approach: Urol Case Rep, 2016; 10; 38-41

21.. Pasqual E, Bertolissi F, Grimaldi F, Adrenal angiosarcoma: Report of a case: Surg Today, 2002; 32; 563-65

22.. Sung JY, Ahn S, Kim SJ, Angiosarcoma arising within a long-standing cystic lesion of the adrenal gland: A case report: J Clin Oncol, 2013; 31; e132-36

23.. Ferrozzi F, Tognini G, Bova D, Hemangiosarcoma of the adrenal glands: CT findings in two cases: Abdom Imaging, 2001; 26; 336-39

24.. Bosco PJ, Silverman ML, Zinman LM, Primary angiosarcoma of adrenal gland presenting as paraneoplastic syndrome: Case report: J Urol, 1991; 146; 1101-3

25.. Croitoru AG, Klausner AP, McWilliams G, Unger PD, Primary epithelioid angiosarcoma of the adrenal gland: Ann Diagn Pathol, 2001; 5; 300-3

26.. Ben-Izhak O, Auslander L, Rabinson S, Epithelioid angiosarcoma of the adrenal gland with cytokeratin expression. Report of a case with accompanying mesenteric fibromatosis.: Cancer, 1992; 69; 1808-12

27.. Jorda M, De MB, Nadji M, Calretinin and inhibin are useful in separating adrenocortical neoplasms from pheochromocytomas: Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol, 2002; 10; 67-70

28.. Jo VY, Fletcher CD: Pathology, 2014; 46; 95-104

29.. Stockman DL, Hornick JL, Deavers MT, ERG and FLI1 protein expression in epithelioid sarcoma: Mod Pathol, 2014; 27; 496-501

30.. Maňáková T, Hojný J, Sedlář M, Epithelioid sarcoma with retained INI1 expression as a cause of a chronic leg ulcer: SAGE Open Med Case Rep, 2022; 10 2050313X221106259

31.. Takizawa K, Kohashi K, Negishi T, A exceptional collision tumor of primary adrenal angiosarcoma and non-functioning adrenocortical adenoma: Pathol Res Pract, 2017; 213; 702-5

32.. Wenig BM, Abbondanzo SL, Heffess CS, Epithelioid angiosarcoma of the adrenal glands. A clinicopathologic study of nine cases with a discussion of the implications of finding “epithelial-specific” markers.: Am J Surg Pathol, 1994; 18; 62-73

33.. Lepoutre-Lussey C, Rousseau A, Al Ghuzlan A, Primary adrenal angiosarcoma and functioning adrenocortical adenoma: An exceptional combined tumor: Eur J Endocrinol, 2012; 166; 131-35

34.. Cornejo KM, Hutchinson L, Cyr MS, MYC analysis by fluorescent in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry in primary adrenal angiosarcoma (PAA): A series of four cases: Endocr Pathol, 2015; 26; 334-41

Figures

In Press

06 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942937

12 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943244

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943275

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943411

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250