18 April 2024: Articles

Potential Indicators of Intestinal Necrosis in Portal Venous Gas: A Case Report of an 82-Year-Old Woman on Long-Term Hemodialysis with Ascites and Pneumatosis Coli

Management of emergency care

Yoshio Hisata12AEF, Naoko E. Katsuki1AEF, Masaki Tago1AEG*, Tomoyo Nishi1E, Tomotaro Nakashima1E, Yoshimasa Oda13E, Shu-ichi Yamashita1EDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942966

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e942966

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Several factors have been reported as possible predictors of intestinal necrosis in patients with portal venous gas (PVG). We describe potential indicators of intestinal necrosis in PVG identified by contrasting 3 episodes of PVG in a patient on hemodialysis against previously verified factors.

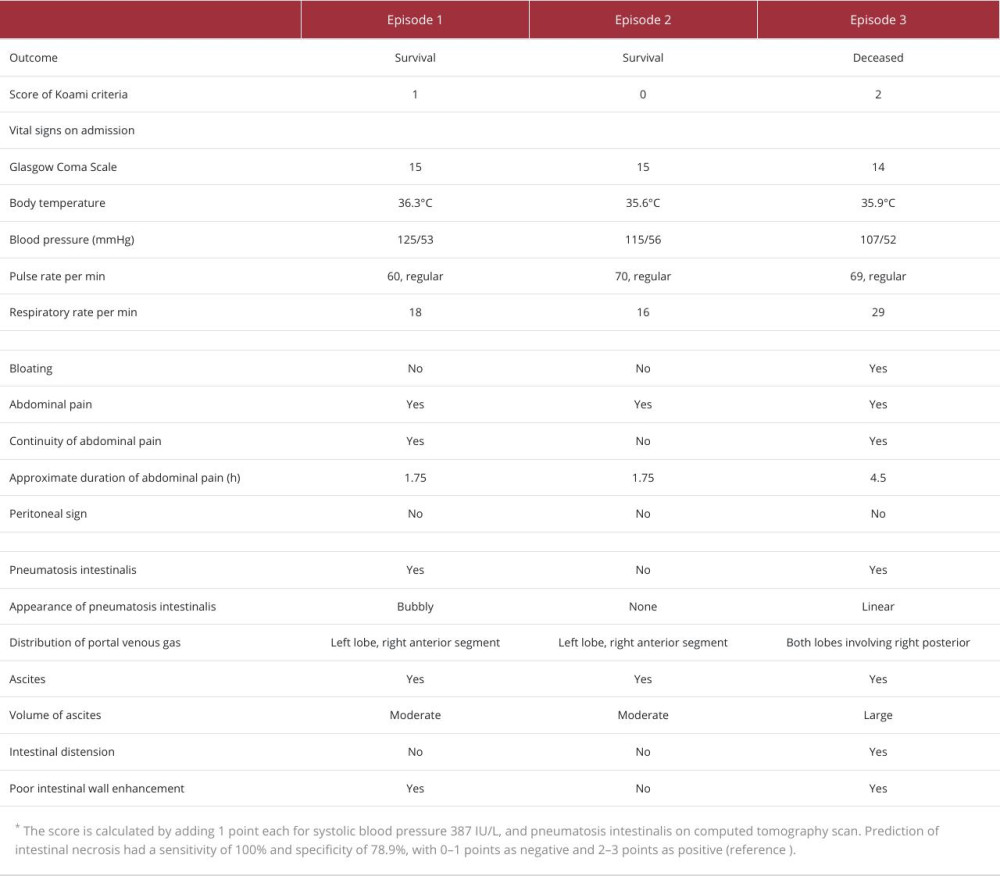

CASE REPORT: An 82-year-old woman undergoing hemodialysis was admitted to our hospital thrice for acute abdominal pain. On first admission, she was alert, with a body temperature of 36.3°C, blood pressure (BP) of 125/53 mmHg, pulse rate of 60/min, respiratory rate of 18/min, and 100% oxygen saturation on room air. Computed tomography (CT) revealed PVG, intestinal distension, poor bowel wall enhancement, bubble-like pneumatosis in the intestinal wall, and minimal ascites. PVG caused by intestinal ischemia was diagnosed, and she recovered after bowel rest and hydration. Three months later, she had a second episode of abdominal pain. BP was 115/56 mmHg. CT revealed PVG and a slight accumulation of ascites, without pneumatosis in the intestinal wall. She again recovered after conservative measures. Ten months later, the patient experienced a third episode of abdominal pain, with BP of 107/52 mmHg. CT imaging indicated PVG, considerable ascites, and linear pneumatosis of the intestinal walls. Despite receiving conservative treatment, the patient died.

CONCLUSIONS: A large accumulation of ascites and linear pneumatosis in the intestinal walls could be potential indicators of intestinal necrosis in patients with PVG caused by intestinal ischemia. As previously reported, hypotension was further confirmed to be a reliable predictor of intestinal necrosis.

Keywords: Intestinal Diseases, Ischemia, Necrosis, Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis, Portal Vein, Renal Dialysis

Introduction

Sever causes of portal venous gas (PVG) have been reported in adult patients, including intestinal ischemia, diverticulosis, inflammatory bowel disease, acute pancreatitis, cholangitis, and appendicitis [1]. Intestinal ischemia accounts for 40% of PVG cases, and the most common cause of intestinal ischemia is non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) [2]. Since the presence of intestinal necrosis reduces the survival rate of NOMI [3,4], a prompt and accurate diagnosis of intestinal necrosis is crucial for prognostication and consideration of surgical intervention [3,5,6]. Patients with PVG and concomitant intestinal necrosis, including patients treated with surgical interventions, have a mortality rate of 59% to 71%, which is higher than that of patients without intestinal necrosis, at 6% to 39% [3,7,8].

Reported risk factors of NOMI include critical illness or significant comorbidities, especially cognitive heart failure, hypovolemia, administration of vasopressor agents, age older than 50 years, history of myocardial infarction, abdominal compartment syndrome, aortic regurgitation, hepatic or renal disease, cardiac or aortic surgeries, and shock states [9]. Especially among patients with renal diseases, the incidence of mesenteric ischemia in patients on hemodialysis has been reported to be 0.3% to 1.9% per patient per year, which is higher than that in individuals who do not undergo hemodialysis [10]. Therefore, predicting intestinal necrosis in patients on hemo-dialysis is important.

Predictors of intestinal necrosis include hypotension, abdominal pain, peritoneal signs, ascites, and elevated levels of serum aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), creatinine (Cr), C-reactive protein (CRP), arterial lactate, pH, and I-FABP [3]. Although bowel distension, pneumatosis intestinalis, poor bowel wall enhancement, porto-mesenteric venous gas, and arterial occlusion have been previously documented as radiological predictors [3,7,8,11–13], sample sizes of the studies were limited or various mesenteric ischemia were included. Herein, we report the case of an older woman on hemodialysis who had 3 consecutive episodes of PVG. Although the patient recovered from the first and second episodes of PVG with conservative treatment, suggestive of a low risk of intestinal necrosis, she unfortunately succumbed to intestinal necrosis after the third episode. Given that the patient exhibited different outcomes despite a similar risk of NOMI throughout the 3 episodes, we compared various factors associated with these instances to identify potential indicators of intestinal necrosis in patients. There have been no previous studies on factors contributing to intestinal necrosis in patients receiving hemodialysis. This report provides insights that can guide further research on factors leading to intestinal necrosis in patients on hemodialysis.

Case Report

EPISODE 1:

An 82-year-old woman, who had been bedridden and receiving hemodialysis for over 10 years for end-stage diabetic nephropathy, had nausea, lower abdominal pain, and acute hypotension (from 114/52 mmHg to 98/46 mmHg), 40 min after the start of a hemodialysis session. Ultrafiltration was terminated, but diffusion was still performed with intravenous etilefrine infused at 2 mg/h. Ultrafiltration was resumed 20 min later, as the patient’s blood pressure rose to 133/55 mmHg. Hemodialysis was again discontinued 10 min later because the patient had cold sweats and lower abdominal discomfort. At dehydration, with a blood flow of 150 mL/min, her symptoms appeared. The dehydration was discontinued, with a total dehydration volume of 0.31 L and a body weight unchanged from pre-dialysis, which was 1.1 kg more than her usual dry weight of 30.8 kg.

The patient’s pertinent medical history included severe constipation, stroke, and spinal stenosis, which were alleviated by taking daily laxatives, clopidogrel, tramadol hydrochloride, and acetaminophen, respectively. Moreover, she had underlying hypertension and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, which were untreated.

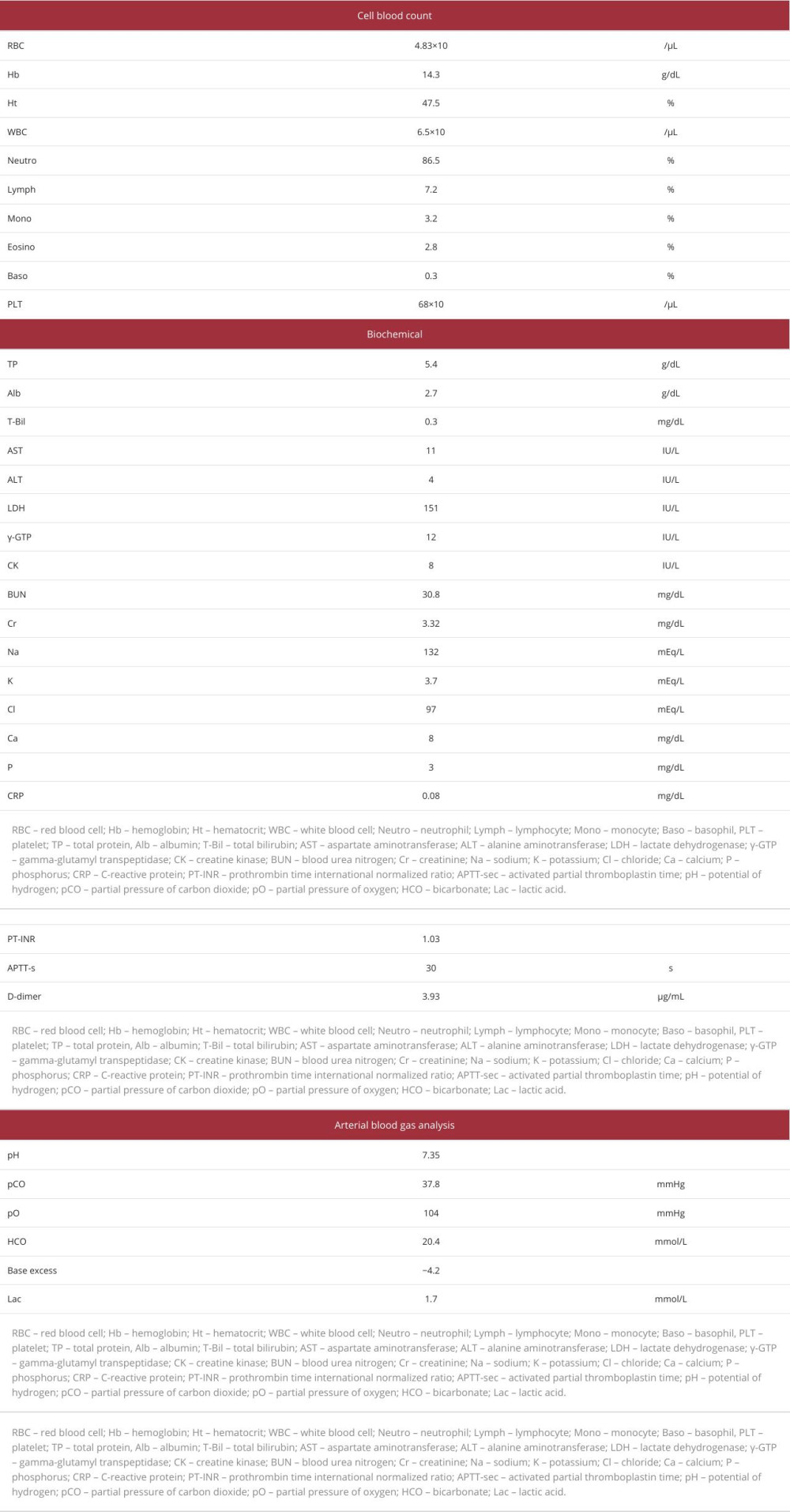

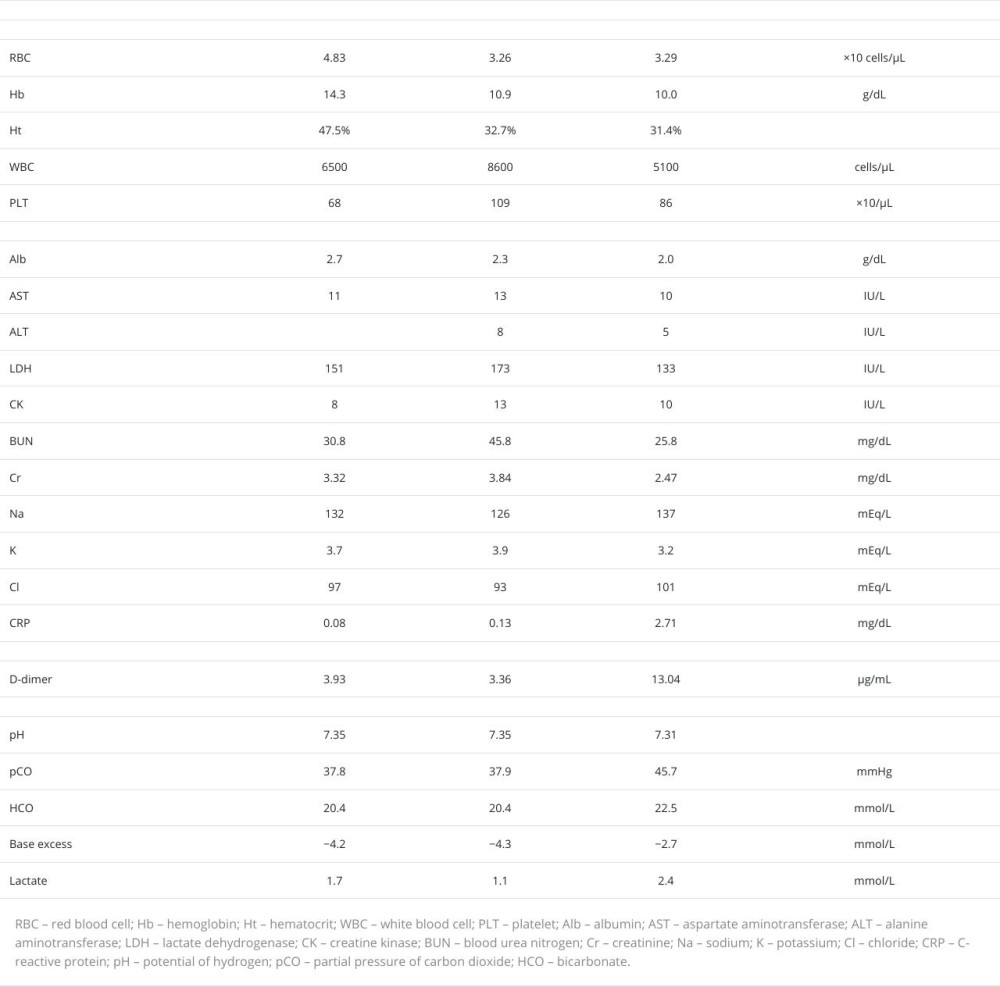

Because a subsequent abdominal CT with contrast enhancement revealed the presence of PVG, the patient was transferred to our hospital. On admission, she was alert, with a body temperature of 36.3°C, blood pressure of 125/53 mmHg, pulse rate of 60 beats/min, regular, respiratory rate of 18 breaths/min, and 100% oxygen saturation on room air. Upon physical examination, the abdomen was noted to be flat and soft without pain, tenderness, or tympany on percussion, although a few bowel sounds were heard (Table 1). Laboratory test results showed a white blood cell count of 6500/μL (neutrophils 86.5%), hemoglobin of level 14.3 g/dL, platelet count of 68×103/μL, D-dimer level of 3.93 μg/mL, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 11 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase level of 4 IU/L, LDH level of 151 IU/L, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level of 30.8 mg/dL, Cr level of 3.32 mg/dL, and CRP level of 0.08 mg/dL. Arterial blood gas analysis showed a pH of 7.35, partial pressure of oxygen of 104 mmHg, partial pressure of carbon dioxide of 37.8 mmHg, and bicarbonate of 20.4 mmol/L (Table 2). Electrocardiography revealed no findings of atrial fibrillation or acute coronary syndrome. Abdominal CT with contrast enhancement revealed some low-density areas, indicative of air in the portal veins of the peripheral and ventral segments of the left hepatic lobe, anterior segment of the right hepatic lobe (Figure 1A), and wall of the small intestine, which were not linear but circular and bubble-like (Figure 1B, 1C). While the enhancement of some parts of the small intestine wall was poor, the amount of ascites was scarce, without intestinal dilatation (Figure 1B). No occlusive lesions due to thrombus or embolism were detected in the abdominal arteries. No findings suggestive of liver cirrhosis, hemorrhage, or infectious disease were observed.

The patient’s prediction score for the risk of intestinal necrosis, based on a report by Koami et al, was 1 point for pneumatosis intestinalis, indicating a low risk [8]. Subsequently, NOMI and PVG induced by hemodialysis, without intestinal necrosis, was diagnosed. Since the patient’s abdominal pain had resolved on admission and the possibility of intestinal necrosis was low, the risk of surgical complication was considered higher than its benefits. The patient rapidly recovered after bowel rest and intravenous fluid rehydration. A fluid infusion of 720 mL/day was administered on hospitalization day 1 and day 2 and 690 mL/day was administered on day 3. Sulbactam sodium 3 g/day was administered since admission. On day 2, the patient was dehydrated 0.3 kg slowly over 3.5 h, with a blood flow of 150 mL/min by hemodialysis with an extra-corporeal ultrafiltration method. After dehydrating 0.7 kg on day 3, she underwent dialysis 3 times a week to maintain her weight on admission, a target weight which was 1.3 kg higher than her previous dry weight.

An abdominal CT taken on day 5 showed the disappearance of low-density areas in the portal vein. The patient was not treated with anticoagulation therapy, because she had a high risk of serious bleeding due to hypertension, hemodialysis, history of stroke, old age, and use of antiplatelet medication [14]. Her electrocardiogram during hospitalization showed sinus rhythm, and enhanced CT showed no occlusive thrombus. The cause of thrombocytopenia was not pursued, because the level of thrombocytopenia did not require a blood transfusion, she had normal coagulation function on hemodialysis, and she was bedridden and unable to perform activities of daily living. The thrombocyte count remained stable at 74×103/μL, and the ratio of reticulum platelets was 1.7% on day 3. The patient’s abdominal pain resolved and did not recur, despite advancing to oral food intake, and she was discharged on day 9.

EPISODE 2:

Three months after episode 1, the patient was again transferred to our hospital because of nausea and epigastric pain, immediately before undergoing percutaneous transcatheter angioplasty for a dialysis shunt. All symptoms resolved upon admission. The patient was alert, with a blood pressure of 115/56 mmHg and a regular pulse. Other vital signs were un-remarkable. The abdomen was noted to be flat and soft, without pain, tympany on percussion, or tenderness, although a few bowel sounds were heard (Table 1). Laboratory investigations revealed an AST level of 13 IU/L, LDH level of 173 IU/L, Cr level of 3.84 mg/dL, and CRP level of 0.13 mg/dL (Table 3). Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT imaging revealed low-density areas, with values consistent with air in the portal veins of the left hepatic lobe and anterior segment of the right hepatic lobe (Figure 2A). Although a minimal amount of ascites was noted, neither a low-density area in the intestinal wall nor distension of the small intestine was observed (Figure 2B). No occlusive lesions due to thrombus or embolism were detected in the abdominal arteries, and NOMI was diagnosed. The predictive score for intestinal necrosis was 0, indicating a negative probability of intestinal necrosis [8]. Subsequently, PVG without intestinal necrosis was diagnosed and determined to be triggered by dehydration from fasting before percutaneous transcatheter angioplasty. Since the patient’s abdominal pain had resolved by the time of arrival at the hospital and the possibility of intestinal necrosis was low, the risk of surgical complications was considered higher than its benefits. The patient recovered after conservative treatment alone.

EPISODE 3:

Ten months after episode 2, the patient experienced severe vomiting and diarrhea lasting for 5 days. Because her symptoms improved after fasting and intravenous fluid administration, an oral diet was resumed on day 6. However, on the following day, she was re-admitted to our hospital because of severe, persistent, generalized abdominal pain that was accompanied by cold sweats. Upon arrival, her Glasgow Coma Scale score was 14, with an eye response of 4, verbal response of 4, and motor response of 6. Her blood pressure was 107/52 mmHg, pulse rate was 69 beats/min and regular, and respiratory rate of 29 breaths/min. Her abdomen was slightly distended and tympanitic on percussion, a finding not observed in episodes 1 or 2. There were no signs of peritoneal irritation. Laboratory tests showed the following levels: BUN of 25.8 mg/dL, Cr of 2.47 mg/dL, LDH of 133 IU/L, D-dimer of 13.04 μg/mL, and CRP of 2.71 mg/dL (Table 3).

Abdominal CT with contrast enhancement revealed low-density areas, with CT values consistent with air in the portal veins that were widely distributed in both hepatic lobes, including the right posterior segment (Figure 3A). Linear low-density areas with the same CT values in the intestinal wall and a dis-tended small intestine indicated linear pneumatosis intestinalis (Figure 3B–3D). Further, a large amount of ascites was observed on the surface of the liver and in the Douglas pouch (Figure 3A). Because these findings yielded a prediction score of 2 points [8], positively indicating intestinal necrosis, the patient consequently received a diagnosis of PVG and intestinal necrosis caused by intestinal ischemia. No occlusive lesions due to thrombus or embolism were detected in the abdominal arteries, and NOMI was diagnosed. Although surgery was indicated, her family members declined to give consent due to the significant risks involved and the patient’s impaired ability to perform daily activities, caused by her chronic bedridden state. She died 5 h after admission despite conservative treatment that involved intravenous administration of a significant amount of fluid and vasopressors.

Discussion

Hemodialysis is a major risk factor for mesenteric ischemia [10]. Because our patient had undergone dialysis for many years, it is probable that all 3 episodes of abdominal pain were caused by secondary intestinal ischemia [7]. In the present case, in addition to her renal disease, requiring hemodialysis, several events, including multifactorial hypovolemia, advanced age observed in all 3 episodes, and the use of vasopressor agents in episode 1, were identified as general risks for NOMI [9]. Specifically, advanced age and duration of hemodialysis have been reported as risks for NOMI, with the duration of hemo-dialysis also noted as a risk for the recurrence of NOMI in patients undergoing hemodialysis [15].

Predicting the presence of intestinal necrosis in patients with intestinal ischemia is crucial for determining the need for surgical intervention. Evidence suggests that patients with intestinal necrosis have a much higher mortality rate if surgery is unsuccessful than do those without intestinal necrosis [7,8]. Based on the Koami criteria [8], it is reasonable to assume that this patient had intestinal necrosis only in the third episode, as the previous 2 episodes of PVG resulted in survival, but the last one in death. Furthermore, the risk of intestinal necrosis was low in the first 2 episodes yet high in the final episode.

Variations in CRP levels, base excess, and lactate levels were observed in all 3 episodes, as shown in Table 3. Variations in the amount of ascites, presence of pneumatosis intestinalis on abdominal CT, and blood pressure on admission were also observed in all 3 episodes, as shown in Table 1. Ascites was observed in all 3 episodes, although in small amounts on the liver surface in episodes 1 and 2, contrasting with the massive quantity surrounding the liver and pelvis in episode 3 (Figure 3A). Moreover, the span of water density areas on the liver surface, indicative of ascites, notably increased from episode 1 (23 mm) to episode 2 (31 mm) and to episode 3 (91 mm), indicating a much larger amount of ascites in episode 3 than in the previous episodes. Whether the amount of ascites can predict intestinal necrosis in patients with PVG is debated in studies [7,8]. Research on patients with upper gastrointestinal perforation revealed that conservative treatment is a viable option for ascites ≤5 mm thick on the liver surface or as-cites ≤60 mL in the bladder-rectal fossa or Douglas pouch [16]. However, it is important to note that the above study did not include patients with PVG and intestinal ischemia. In our patient, the amount of ascites in episode 3 was substantially larger than that in episodes 1 or 2. Moreover, the combined amount of ascites from all 3 episodes was larger than that in the study mentioned above

The occurrence of pneumatosis intestinalis in patients with PVG, as documented in episodes 1 and 3 in our patient, can be useful in predicting the presence of intestinal necrosis [8]. Pneumatosis intestinalis is pathologically classified into 2 types: cystic and non-cystic [12]. While cystic forms naturally tend to appear bubble-like, the linear appearance of gas indicates the presence of non-cystic forms [12]. The cystic form is characterized by a thin wall surrounding hydrogen gas generated by intestinal bacteria, which does not communicate with the intestinal lumen. In contrast, pneumatosis usually communicates with the intestinal lumen, indicating the presence of transmural lesions or irreversible gastrointestinal necrosis in the non-cystic form [12]. The mechanisms and pathophysiology of pneumatosis intestinalis related to intestinal ischemia have not been established; however, chemical and bacterial theories have been reported [12]. One theory is that gas enters the gastrointestinal mucosa, leading to detachment from the mucosa and increased local intraluminal pressure, secondary to gastrointestinal obstruction. Another theory is that gas, formed by breeding anaerobic bacterial growth, penetrates the intestinal wall because of increased mucosal permeability [12]. The theories suggesting that pneumatosis intestinalis reflects the condition of the disease support our case findings. We consider the possibility that the cystic pneumatosis gas pattern progressed from bubbly to linear as a result of a longer clinical course or severity of the disease. A case series reported bubbly intestinal pneumatosis intestinalis as benign, although there was no strong evidence [17]. Considering the pathological characteristics of pneumatosis intestinalis, a linear configuration could potentially predict the presence of intestinal necrosis on CT [12]. Although our patient had gas lesions in the intestinal wall in 2 episodes, their bubble-like appearance in the first episode was associated with survival, while their linear appearance in the final episode was associated with mortality. No study has examined the association between intestinal pneumatosis and intestinal necrosis with NOMI in patients on hemodialysis. However, in light of the fatal outcome of the last episode and a study suggesting that the presence of a linear or ring appearance of pneumatosis intestinalis in patients with PVG necessitates surgical intervention [18], it can be inferred that a linear appearance of pneumatosis intestinalis could indicate the presence of intestinal necrosis. Additionally, a previous case report documented intestinal necrosis presenting as a linear appearance of pneumatosis intestinalis in a patient on hemodialysis [19].

A past investigation that reported hypotension as a predictive factor of intestinal necrosis showed that patients with PVG complicated by intestinal necrosis had lower systolic blood pressure than those without (91.5 mmHg vs 112.4 mmHg) [8]. Multivariate analysis also indicated that a decrease in blood pressure increases the probability of intestinal necrosis [8], consistent with our patient’s outcome. However, in an observational study, all patients with NOMI on hemodialysis had lower blood pressure than before the onset [15], suggesting caution in setting a cutoff point to differentiate the presence of intestinal necrosis. Although in episodes 1 and 2, the patient was normotensive on admission, despite a history of hypertension, in episode 3, our patient had a systolic blood pressure of 107 mmHg, which was lower than the prior 2 episodes, meeting the Koami criteria for intestinal necrosis, a systolic blood pressure <108 mmHg [8]. Thus, our case report affirms that the cutoff point of 108 mmHg for blood pressure in the study by Koami et al is reasonable [8]. The decrease in blood pressure during and after hemodialysis certainly leads to a decrease in mesenteric circulating blood volume, thereby increasing the risk of mesenteric ischemia [20]. Paradoxically, the endotoxic shock brought about by intestinal necrosis can cause hypotension [21]. The patient’s blood pressure reading should be reviewed during each admission to investigate its potential to predict intestinal necrosis.

Focusing on the vital signs and image findings from the factors varied in the 3 episodes, we discussed blood pressure, amounts of ascites, and gas images of pneumatosis as candidate indicators for intestinal necrosis. However, these suggestions are based on a single case report, so further research is required for generalization and confirmation.

Conclusions

The presence of a large amount of ascites and linear pneumatosis intestinalis on CT imaging may serve as novel indicators of intestinal necrosis in patients with PVG caused by probable intestinal ischemia. A study focusing on the volume of ascites and the appearance of intestinal pneumatosis is required for confirmation. Previous studies have verified hypo-tension as a useful predictor of intestinal necrosis. Including imaging findings, such as properties of ascites and pneumatosis intestinalis, with clinical findings would support the differentiation between ischemia and necrosis of the bowel wall, facilitating prognostication or consideration of surgical intervention.

Figures

References:

1.. Abboud B, Hachem JE, Yazbeck T, Doumit C, Hepatic portal venous gas: Physiopathology, etiology, prognosis and treatment: World J Gastroenterol, 2009; 15; 3585-90

2.. Fujii M, Yamashita S, Tanaka M, Clinical features of patients with hepatic portal venous gas: BMC Surg, 2020; 20; 300

3.. Bourcier S, Ulmann G, Jamme M, A multicentric prospective observational study of diagnosis and prognosis features in ICU mesenteric ischemia: The DIAGOMI study: Ann Intensive Care, 2022; 12; 113

4.. Verdot P, Calame P, Winiszewski H, Diagnostic performance of CT for the detection of transmural bowel necrosis in non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia: Eur Radiol, 2021; 31; 6835-45

5.. Nelson AL, Millington TM, Sahani D, Hepatic portal venous gas: The ABCs of management: Arch Surg, 2009; 144; 575-81

6.. Trenker C, Görg C, Dong Y, Portal venous gas detection in different clinical situations: Med Ultrason, 2023; 25; 296-303

7.. Higashizono K, Yano H, Miyake O, Postoperative pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) and portal venous gas (PVG) may indicate bowel necrosis: A 52-case study: BMJ Surg, 2016; 16; 42

8.. Koami H, Isa T, Ishimine T, Risk factors for bowel necrosis in patients with hepatic portal venous gas: Surg Today, 2015; 45; 156-61

9.. Gnanapandithan K, Feuerstadt P, Review article: Mesenteric ischemia: Curr Gastroenterol Rep, 2020; 22; 17

10.. Bassilios N, Menoyo V, Berger A, Mesenteric ischaemia in haemodialysis patients: A case/control study: Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2003; 18; 911-17

11.. Okada M, Sato M, Kimura A, Evaluation of elderly patients with abdominal pain in an Emergency Department: Factors associated with emergency surgery: Journal of Japanese Association for Acute Medicine, 2006; 17; 45-52

12.. Soyer P, Martin-Grivaud S, Boudiaf M, Linear or bubbly: A pictorial review of CT features of intestinal pneumatosis in adults: J Radiol, 2008; 89; 1907-20

13.. Zeng Y, Yang F, Hu X, Radiological predictive factors of transmural intestinal necrosis in acute mesenteric ischemia: Systematic review and meta-analysis: Eur Radiol, 2023; 33; 2792-99

14.. Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: The Euro Heart Survey: Chest, 2010; 138; 1093-100

15.. Quiroga B, Verde E, Abad S, Detection of patients at high risk for nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia in hemodialysis: J Surg Res, 2013; 180; 51-55

16.. Sasaki R, Karasaki T, Nomura Y, [Quantitative risk assessment of as-cites in patients with perforation of the upper gastrointestinal tract using computed tomography.]: Nihon Hukubu Kyukyu Igakukai Zassi, 2015; 35; 383-88 [in Japanese]

17.. Sassi C, Pasquali M, Facchini G, Pneumatosis intestinalis in oncologic patients: When should the radiologist not be afraid?: BJR Case Rep, 2016; 3; 20160017

18.. Muratsu A, Muroya T, Yui R, Factors associated with bowel necrosis in patients with hepatic portal venous gas and pneumatosis intestinalis: Acute Med Surg, 2020; 7; e432

19.. Francés CG, Tamayo Rodriguez ME, Marín-Blázquez AA, Non-oclusive mesenteric ischemia as a complication of dialysis: Rev Esp Enferm Dig, 2021; 113; 731-32

20.. Seong EY, Zheng Y, Winkelmayer WC, The relationship between intradialytic hypotension and hospitalized mesenteric ischemia: A case-control study: Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2018; 13; 1517-25

21.. Marshall JC, Foster D, Vincent JL, Diagnostic and prognostic implications of endotoxemia in critical illness: results of the MEDIC study: J Infect Dis, 2004; 190; 527-34

Figures

In Press

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943467

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943376

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942853

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942660

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250