13 July 2022: Articles

Esophagopericardial Fistula and Pneumopericardium as a Complication of Pulmonary Vein Isolation in a 62-Year-Old Man with Atrial Fibrillation: A Case Report

Mistake in diagnosis, Diagnostic / therapeutic accidents, Management of emergency care, Rare disease, Educational Purpose (only if useful for a systematic review or synthesis)

Ndausung Udongwo1ABCDEF*, Dhaval Desai2ABCD, Ann Kozlik1ABEF, Justin Ilagan1CEF, Saira Chaughtai1ACDFG, Eran S. Zacks2ACFDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.936315

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936315

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Pulmonary vein isolation is a method of cardiac ablation therapy used to treat irregular heart rhythm, including atrial fibrillation (AF). This report presents a case of esophagopericardial fistula (EPF) and pneumopericardium as a complication of pulmonary vein isolation in a 62-year-old man with AF.

CASE REPORT: We report the rare case of a 62-year-old man with a medical history of persistent atrial fibrillation status after ablation 3 days prior to his initial Emergency Department visit for chest pain. Acute coronary syndrome was ruled out with normal electrocardiogram, echocardiography, and troponin tests. Fluid overload and sotalol adverse effects were presumed to be the cause of his symptoms. We discontinued sotalol with diuresis and he was discharged home when his chest pain subsided. Nine days later, he returned to the Emergency Department with worsening similar symptoms and was eventually diagnosed with EPF and pneumopericardium on a computed tomography scan of the chest with contrast. He was managed with esophagogastroduodenoscopy and stent placement along with subxiphoid pericardial window and pericardial drain placement. The patient was discharged in stable condition after removing the pericardial drain. At 10-day and 1-month follow-up, he had no recurrent symptoms.

CONCLUSIONS: This report shows that although EPF with pneumopericardium is a rare complication of pulmonary vein isolation, it should be rapidly diagnosed and treated as a life-threatening emergency.

Keywords: Atrial Fibrillation, Chest Pain, Esophageal Fistula, Pneumopericardium, radiofrequency ablation, Fistula, Humans, Male, Middle Aged, Pulmonary Veins, Sotalol

Background

The method of pulmonary vein isolation involves either a single-shot or point-by-point ablation of the 4 pulmonary veins by linear lesions around their antrum [1]. It is indicated in symptomatic patients with paroxysmal/persistent atrial fibrillation (AF) who failed antiarrhythmic drug therapy (class I or III), those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and AF medicated tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy [1]. Several complications associated with this procedure range from life-threatening complications (eg, cardiac tamponade, periprocedural death, esophagopericardial fistula [EPF]) to those of unknown significance (eg, asymptomatic cerebral embolism) [1,2]. EPF is 10 times rarer than atrioesophageal fistula. Its presentation varies and can include chest pain, dysphagia, fever, nausea, vomiting, and hematemesis. Only a few cases of this unusual defect have been reported in the literature [3–5]. We report a case of EPF and pneumopericardium as a complication of pulmonary vein isolation in a 62-year-old man with AF.

Case Report

A 62-year-old mane with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, class 1 obesity, coronary artery disease with 40% left anterior descending artery stenosis, atrial flutter and persistent atrial fibrillation status after ablation 6 years prior, and recent ablation (12 days prior) presented to the Emergency Department with worsening pleuritic chest pain at rest that started 2 days before admission. It was 10/10 in severity, pressure-like, non-radiating, worse when lying supine, and mildly alleviated by sitting upright. It was associated with cough and dyspnea on exertion. He denied any fever, diaphoresis, nausea/vomiting, recent travel history, or sick contacts. Of note, he presented to the Emergency Department with similar concerns about 3 days after ablation. At that time, after acute coronary syndrome was ruled out and his symptoms were attributed to an adverse effect from sotalol and fluid overload. Electrocardiogram, chest X-ray, and echocardiography (2D-ECHO) results were unremarkable. He received scheduled furosemide, sotalol was discontinued, and he was discharged after his symptoms improved. His family history was remarkable for myocardial infarction in his mother and brother at age 65 and 54, respectively. He denied any use of tobacco or illicit drugs in the past and drank alcohol occasionally. Home medications were atorvastatin 10 mg daily, apixaban 5 mg twice daily, metoprolol tartrate 12.5 mg twice daily, and quinapril 10 mg daily.

On initial assessment, vitals were blood pressure of 143/85 mmHg, heart rate of 87 beats per minute, temperature of 36.6°C, respiratory rate of 21 breaths per minute, heart rate of 83 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation of 98% on ambient air. Although he appeared uncomfortable due to chest pressure, his cardiopulmonary examinations were unremarkable, with no murmurs, rubs, gallops, Kussmaul sign, jugular venous distention, bilateral lower extremity edema, wheezes, or rales.

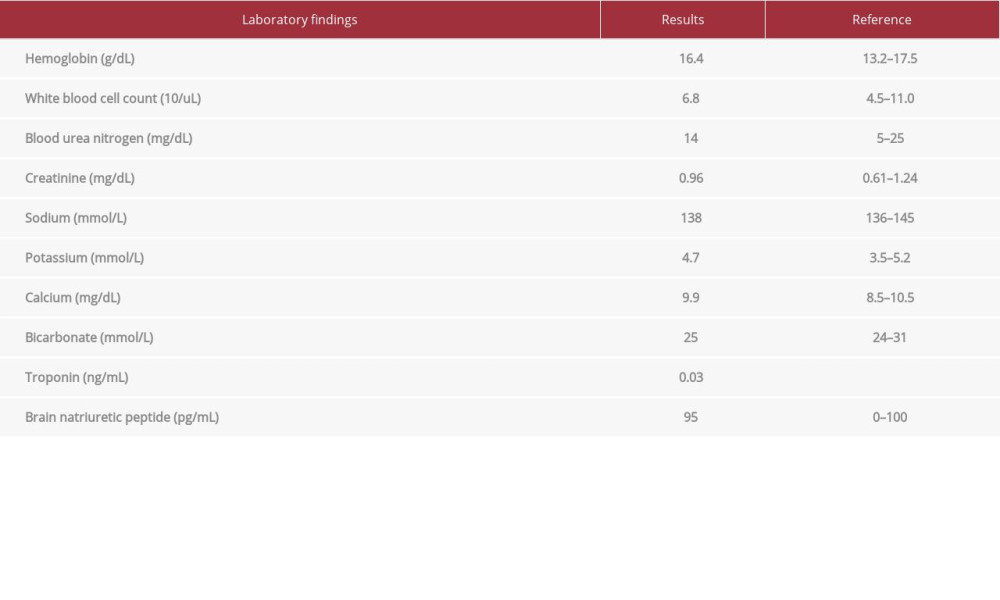

An electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm, rate of 75 beats per minute, premature atrial complexes, right bundle branch block with no ST/T wave abnormalities, unchanged from prior. A chest X-ray showed a moderately enlarged cardiac silhouette with focal left basilar opacity. Initial troponin was normal, as shown in Table 1. Laboratory results, including brain natriuretic peptide level, were unremarkable (Table 1). Due to his recent symptoms following a recent pulmonary vein isolation done 12 days prior, a computed tomography angiogram of the chest was performed and demonstrated a moderatesize focus of gas anteriorly within the pericardial sac, confirming pneumopericardium (Figure 1A–1D). Limited 2D-ECHO also confirmed pneumopericardium with no tamponade physiology. EPF as a sequela of radiofrequency ablation was suspected.

He was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics (vancomycin/piperacillin-tazobactam). The patient was immediately taken to the operating room. Using fluoroscopic guidance, a 1.5-cm mid-esophageal perforation was noted, and an esophageal stent was placed via esophagogastroduodenoscopy (Figure 2). Furthermore, a subxiphoid pericardial window with drain/tube was placed and he was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit for monitoring.

The patient tolerated the procedure with no complications. His hospital course was complicated with intermittent episodes of mild chest pain, leukocytosis, and a small leakage along the upper aspect of the distal esophageal stent that was managed conservatively (Figure 3). An antifungal was added to his regimen while his cultures remained negative. He tolerated oral intake well, the pericardial drain was removed, and he was discharged in stable condition on post-operative day 7. Our patient did not have a follow-up 2D-ECHO or computed tomography angiography done after recovery. There were no new concerns in his outpatient follow-up visits on postoperative days 10 and 31.

Discussion

The incidence of esophagopericardial fistula (EPF) ranges is 0.016–0.04% [3,6]. It has protean clinical presentations, but chest pain with/without fever is common [7,8]. Abnormal laboratory findings, particularly leukocytosis, have also been reported to be a common diagnostic sign in patients with this iatrogenic defect [8,9]. EPF is about 10 times rarer than atrioesophageal fistula as a complication [7]. Due to its rarity, there are limited data available on its common clinical presentations and specific management [7].

Our patient initially presented with chest pain and shortness of breath 3 days after RFA. The workup, including electrocardiogram, troponin levels, chest X-ray, and echocardiogram, ruled out acute coronary syndrome or pulmonary pathologies. Sotalol was discontinued and he was only treated with furosemide and analgesics. There were no concerns for sepsis during his short visit to the hospital, and he was discharged when his symptoms subsided. Nine days later, he presented with worse symptoms and was then diagnosed with EPF with concomitant pneumopericardium. Misdiagnosis of this rare complication could have been fatal. Our patient already had radiofrequency ablation (RFA) done in the past, which could have increased the risk for these complications, yet it was missed on his initial visit.

Veseli et al presented a case of a 59-year-old man with persistent atrial fibrillation who was admitted to another hospital with severe chest pain radiating to the back, 24 days after undergoing pulmonary vein isolation. An initial chest tomography scan ruled out aortic dissection, but echocardiography revealed a small amount of pericardial fluid [3]. The patient’s hospital course became worse and he even required mechanical circulatory support (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and intra-aortic balloon pump [IABP]) [3]. The patient was discharged to a rehabilitation center after 50 days, while ours was discharged home after 7 days [3]. Although symptoms can present in ≤2 months, there should be a high index of suspicion for esophageal rupture and EPF in patients with similar presentations between 3–35 days after RFA [6,7].

In addition to RFA, several risk factors, including infections (eg, syphilis, candida, herpes), caustic agents, trauma, and malignancy, can lead to EP with progression to EPF and concomitant pneumopericardium [10,11]. There are several proposed pathophysiologic mechanisms associated with this defect, including thermal injury to the esophagus, anatomical proximity of the esophagus to the left atrium, a history of gastric reflux prior to RFA, and a lack of protective layer (serosa) in the esophageal lining may contribute to EP with progression to EPF [3,7,12].

RFA can lead to mutilation of surrounding esophageal vessels (arteries/nerves), which can result in ischemic esophageal ulcerations from acid reflux due to decreased motility and inflammatory response [7]. Over the years, some modalities have been recommended for prevention, including mapping techniques such as Carto®, a temperature probe, Intracardiac Echocardiography (ICE), or barium paste [3,13]. Of note, Carto® was utilized during our patient’s recent pulmonary vein isolation, but unfortunately did not stop the occurrence of EPF.

In a non-randomized prospective cohort study published by Koruth et al comparing the effects of biphasic pulsed-field ablation (PFA) versus RFA on esophageal injury, 10 female Yorkshire swine were euthanized 25 days after catheter ablation; 60% (6) underwent PFA and 40% underwent RFA [14]. Histological examination on all 6 of the PFA porcine group showed no esophageal injury on autopsy (0/6). However, all 4 (4/4, 100%) of the RFA porcine group had esophageal injury [14]. In addition, in a prospective clinical trial (first-in-human pilot study) known as the Pulsed Field Ablation to Irreversibly Electroporate Tissue and Treat AF (PULSED AF), there were no serious adverse events, including esophageal injury, cerebrovascular accident, or death, with the use of biphasic PFA in 38 participants at 30-day follow-up [15]. We hope that with advances in medicine, the PFA approach will help reduce the incidence of complications associated with catheter ablation.

Computed tomography scan of the chest with contrast (oral/intravenous) is the most reliable imaging test recommended in diagnosing pneumopericardium and EPF [2–7]. In 33 of 39 EPF cases reported in the literature, 85% survived without major adverse effects [7], 34 out of 40 with the present patient. The management of EPF is dependent on the clinical presentation, making it a non-specific approach. Surgical explorations, esophageal stenting, pericardial drains, and conservative management (eg, antibiotics) are some of the reported management strategies associated with this defect [7]. In summary, early detection and treatment of this unusual defect may help reduce morbidity/mortality.

Conclusions

Esophagopericardial fistula (EPF) is 10 times rarer, with decreased prognosis and mortality, than atrioesophageal fistula. Computed tomography scan of the chest with contrast (oral/intravenous) remains the most reliable imaging modality for diagnosing EPF. Biphasic pulsed-field ablation has been shown to have better follow-up outcomes in patients receiving catheter ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation when compared to radiofrequency ablation. A delay in recognizing EPF could have been fatal in our patient. However, it was caught in a timely fashion and addressed, with an excellent outcome. This report has shown that although EPF with pneumopericardium is a rare complication of pulmonary vein isolation, it should be rapidly diagnosed and treated as a life-threatening emergency.

Figures

References:

1.. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC: Eur Heart J, 2021; 42(5); 373-498 [Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021;42(5):507; Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021;42(5):546–47; Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021;42(40):4194]

2.. Weinmann K, Aktolga D, Pott A, Impact of re-definition of paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation in the 2012 and 2016 European Society of Cardiology atrial fibrillation guidelines on outcomes after pulmonary vein isolation: J Interv Card Electrophysiol, 2021; 60(1); 115-23

3.. Veseli G, Iwai S, Jacobson JT, Survival of a patient with an esophagopericar-dial fistula after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: a case report and literature review: J Innov Card Rhythm Manag, 2020; 11(5); 4091-98

4.. Chavez P, Messerli FH, Casso Dominguez A, Atrioesophageal fistula following ablation procedures for atrial fibrillation: Systematic review of case reports: Open Heart, 2015; 2(1); e000257

5.. Zakaria A, Hipp K, Battista N, Fatal esophageal-pericardial fistula as a complication of radiofrequency catheter ablation: SAGE Open Med Case Rep, 2019; 7; 2050313 X19841150

6.. Seo JM, Park JS, Jeong SS, Pericardial-esophageal fistula complicating atrial fibrillation ablation successfully resolved after pericardial drainage with conservative management: Korean Circ J, 2017; 47(6); 970-77

7.. Deneke T, Sonne K, Ene E, Esophagopericardial fistula: The Wolf in sheep’s clothing: JACC Case Rep, 2021; 3(8); 1136-38

8.. Dagres N, Kottkamp H, Piorkowski C, Rapid detection and successful treatment of esophageal perforation after radiofrequency ablation of atrial fibrillation: Lessons from five cases: J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol, 2006; 17(11); 1213-15

9.. Cummings JE, Schweikert RA, Saliba WI, Brief communication: Atrial-esophageal fistulas after radiofrequency ablation: Ann Intern Med, 2006; 144(8); 572-74

10.. Mitchell-Brown F, McPherrin M, Radiofrequency ablation-induced esophageal perforation: Nursing, 2018; 48(10); 58-62

11.. Bowman AW, DiSantis DJ, Frey RT, Esophagopericardial fistula causing pyopneumopericardium: Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging, 2020; 2(6); e200417

12.. Halbfass P, Pavlov B, Müller P, Progression from esophageal thermal asymptomatic lesion to perforation complicating atrial fibrillation ablation: A single-center registry: Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol, 2017; 10(8); e005233

13.. Tops LF, Schalij MJ, den Uijl DW, Image integration in catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: Europace, 2008; 10(Suppl. 3); iii48-56

14.. Koruth JS, Kuroki K, Kawamura I, Pulsed field ablation versus radiofrequency ablation: Esophageal injury in a novel porcine model: Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol, 2020; 13(3); e008303

15.. Verma A, Boersma L, Haines DE, First-in-human experience and acute procedural outcomes using a novel pulsed field ablation system: The PULSED AF pilot trial: Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol, 2022; 15(1); e010168

Figures

In Press

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943214

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943010

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943687

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943070

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250