31 March 2023: Articles

Multidrug-Resistant and Methicillin-Resistant Co-Infection in a Nigerian Patient with COVID-19: A Case Report

Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Muinah Adenike FoworaDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.938761

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e938761

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Bacterial Infections, especially, of the respiratory system, have been reported as one of the medical concerns in patients with the Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19), particularly those with multiple co-morbidities. We present a case of a diabetic patient with co-infection of multi-drug-resistant Kocuria rosea and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) who contracted COVID-19.

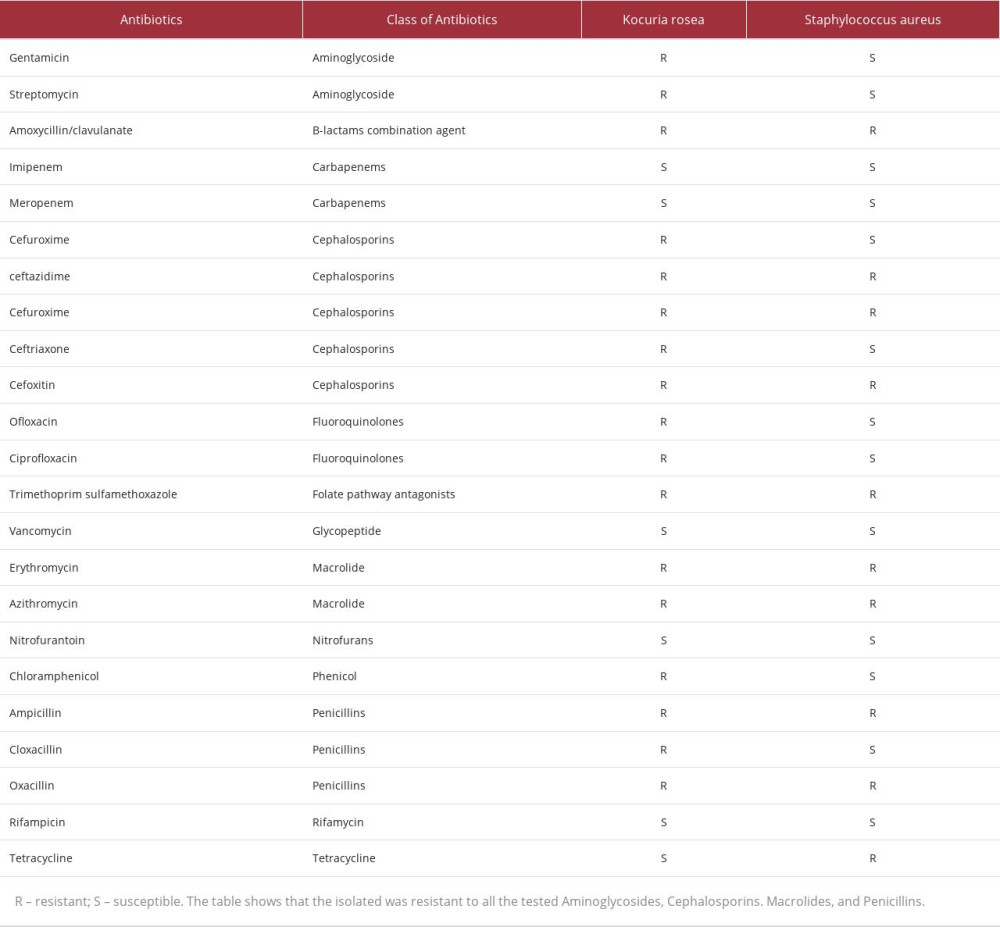

CASE REPORT: A 72-year-old man with diabetes presented with symptoms including cough, chest pain, urinary incontinence, respiratory distress, sore throat, fever, diarrhea, loss of taste, and anosmia and was confirmed to have COVID-19. At admission, he was also found to have sepsis. MRSA was isolated in conjunction with another organism, resembling coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, which was misidentified using commercial biochemical testing systems. The strain was finally confirmed to be Kocuria rosea by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Both strains were highly resistant to multiple classes of antibiotics, but the Kocuria rosea was resistant to all the cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and macrolides tested. The use of ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin did not improve his condition, which ultimately led to his death.

CONCLUSIONS: This case report shows that the presence of multi-drug-resistant bacteria infections can be fatal in patients with COVID-19, especially in patients with other co-morbidities like diabetes. This case report also shows that biochemical testing may be inadequate in identifying emerging bacterial infections and there is a need to include proper bacterial screening and treatment in the management of COVID-19, especially in patients with other co-morbidities and with indwelling devices.

Keywords: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, coinfection, COVID-19, Kocuria rosea, Sepsis, Male, Humans, Aged, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, RNA, Ribosomal, 16S, Staphylococcal Infections, COVID-19, Anti-Bacterial Agents

Background

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), an acute and highly infectious respiratory disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), continues to be a problem globally since its first report in 2019. Fatalities due to this disease has been reported worldwide, with a higher risk of severe infection and, consequently, mortality observed in the elderly, immunocompromised, and patients with co-morbidities and co-infections such as chronic kidney disease, pulmonary disease, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes [1–3]. The increased risk of mortality seen in this demographic has been associated with the onset of opportunistic infections, which further complicates COVID-19 treatment.

Bacterial co-infection has been reported as a substantial impediment to the management of viral respiratory tract infections, resulting to a large increase in morbidity and mortality [4]. In the early cases of COVID-19, attention was not paid to bacterial co-infection in COVID-19 mortality. This may be because most reports do not focus on the prevalence and etiology of bacterial co-infection in COVID-19 patients. However, bacteria co-infection with COVID-19 has been linked to an increased risk of shock, respiratory failure, and longer hospital stay. About 3.5% of patients have been reported to have bacterial co-infection at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis, while 14.3% are classified as secondary bacterial co-infections (SBI), which are bacterial infections contracted after admission with COVID-19 [5]. Most of the bacterial co-infection seen in COVID-19 cases are secondary bacterial co-infections. However,

Case Report

On August 20, 2021, during the third COVID-19 wave in Nigeria, a 72-year-old male Nigerian presented with symptoms of cough, chest pain, urinary incontinence, respiratory distress, sore throat, fever, diarrhea, loss of taste, and anosmia (loss of smell), all characteristics of COVID-19. The patient was confirmed and diagnosed with COVID-19 at the Infectious Diseases Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria. This hospital is a renowned hospital where the index case of COVID-19 was detected in Nigeria.

The hospital uses the Sansure Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Nucleic Acid Diagnostic Kit for COVID-19 diagnosis coupled with symptoms. The kit has been reported to have high sensitivity and has also been endorsed for the diagnosis of COVID-19 [9].

A review of the medical history of the patient showed that he had hypertension and diabetes mellitus but did not have a record of any indwelling devices. He had received a dose of the COVID-19 vaccine 1 week before admission. However, information was not available on which brand of the vaccine and how many doses of the vaccine he had received. There was also no information on how well the patient managed his diabetes, his travel history, or if he had been in contact with someone who travelled into Nigeria.

Physical examination at the time of admission showed he had an oxygen saturation level of 94% with a non-rebreathing face mask (NRFM) at 15 liters per minute (L/min), blood pressure of 170/89 millimeter mercury (mmHg), pulse rate of 108 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 22 cycles per minute, temperature of 37°C, and elevated fasting blood and random blood sugar values of 257 milligram per deciliter (mg/dL) and 365 nanogram per deciliter (ng/dL), respectively. Apart from this, blood examination showed that he also had septicemia, with an elevated white blood cell count of 17×109/L, a neutrophil percentage of 83%, lymphocytes 12%, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) level of 98 mm/h, but all other blood parameters, including platelet counts, were normal. He also had normal electrolytes, urea, and creatinine levels. The patient was catheterized on admission, but it was indicated in the case note that this was later removed. A blood sample was collected for blood culture; however, the results of the blood culture were not available before treatment commenced.

Upon admission, the patient was managed for COVID-19 and associated symptoms with IV ceftriaxone 1g every 12 hours; IV metronidazole 500 milligrams (mg) every hour; IV dexamethasone 8 mg and then 4 mg every 12 hours; subcutaneous enoxaparin 40 mg every 12 hours; Ivermectin tablet 12 mg on days 1, 3, 6, and 7; Zinc tablet 100 mg daily; vitamin C Tablet 1000 mg daily; and vitamin D Tablet 1000 International units (IU) daily. For other co-morbidities, the patient received subcutaneous insulin 10 IU every 8 hours a day and a tablet of amlodipine 10 mg daily. The treatment regimen was well adhered to as the nurses were responsible for instituting the intervention and frequent checks were done on the patients in the isolation wards by the health team to assess tolerability to the interventions. No significant adverse effects were reported throughout the patient’s management.

Follow-up tests during his stay at the center included regular monitoring of vital signs and fasting and random blood sugar level evaluation. At follow-up, the white blood cell count had increased to 19.23×109/L, the neutrophil percentage increased to 89.2%, and the ESR level increased to 105 mm/h.

The fasting and random blood sugars also remained elevated, but all other hematological parameters remained normal. Due to poor glycemic and blood pressure control, the dosage of the subcutaneous insulin was increased, and Glucophage, glibenclamide, Moduretic, and losartan tablets were added to the patient’s regimen. Also, due to the increasing WBC counts and the blood culture results that showed the presence of a presumptive

On September 9, 2021, as part of an on-going study on the nasal bacteria carriage among COVID-19 patients, the nasopharyngeal sample of the patient was collected. The swabs were placed in a tryptone soy broth (TSB) enriched with sodium chloride and a skimmed milk, tryptone soy broth, glycerol, and glucose (STGG) transport medium. The sample in the sodium chloride-enriched TSB was incubated aerobically overnight at 37°C, while the sample in the STGG was incubated microaerophilically overnight at 37°C. The broth was plated on mannitol salt agar, MacConkey agar, blood agar, and nutrient agar. The isolated growth showed a mixed culture of

Based on the exhibited morphological characteristics as identified in the literature [10], the second bacterial isolate was suspected to be a

The isolate presented as non-mannitol fermenting, pale-cream growth on mannitol salt (Figure 1A, 1B), small, smooth, pale-cream colonies on nutrient agar that were indistinguishable from

The suspected

After bacterial identification, both the MRSA strain and the

However, 5 days after collection of the specimen and while bacteria characterization was still on-going, the patient died of complications on September 14, 2021.

Discussion

This case report presents an interesting case of bacterial co-infection in a COVID-19 patient who was living with diabetes as a comorbidity. The 2 bacteria identified in this case were Methicillin-resistant

The association of

One important feature of the case in this report was that the patient was initially catheterized, and the catheter was later removed at admission.

The MRSA and

It is believed that one of the problems that affected the management of this patient was the identification process after blood culture. This is because

The main limitation of this study was that the case record and health history of the patient were not available to the clinicians. The Infectious Disease Hospital (IDH) was the first isolation center for COVID-19 patients in Lagos, Nigeria, and most of the patients admitted at the hospital did not use the hospital as their primary healthcare provider; therefore, their case records may not be available at the IDH. Hence, only information from COVID-19 diagnosis until discharge or otherwise are available.

Conclusions

This case report shows that the presence of multi-drug-resistant bacterial infections can be fatal in patients with COVID-19, especially in patients with other co-morbidities like diabetes. This case report also shows that biochemical testing may be inadequate in identifying rare and emerging bacterial infections and there is a need to include proper bacterial screening and treatment in the management of COVID-19, especially in those with other co-morbidities like diabetes, and for patients with indwelling devices.

Figures

References:

1.. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study: Lancet, 2020; 395(10229); 1054-62

2.. Kenarkoohi A, Maleki M, Ghiasi B, Prevalence, and clinical presentation of COVID-19 infection in hemodialysis patients: J Nephropathol, 2022; 11(1); e07

3.. Mumcuoğlu İ, Çağlar H, Erdem D, Secondary bacterial infections of the respiratory tract in COVID-19 patients: J Infect Dev Ctries, 2022; 16(7); 1131-37

4.. Lai CC, Wang CY, Hsueh PR, Co-infections among patients with COVID-19: The need for combination therapy with non-anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents?: J Microbiol Immunol Infect, 2020; 53(4); 505-12

5.. Russell CD, Fairfield CJ, Drake TM, Co-infections, secondary infections, and antimicrobial use in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 during the first pandemic wave from the ISARIC WHO CCP-UK study: A multicentre, prospective cohort study: Lancet Microbe, 2021; 2(8); 354-65

6.. Abdoli A, Falahi S, Kenarkoohi A, COVID-19-associated opportunistic infections: A snapshot on the current reports: Clin Exp Med, 2022; 22(3); 327-46

7.. Westblade LF, Simon MS, Satlin MJ, Bacterial coinfections in coronavirus disease 2019: Trends Microbiol, 2021; 29(10); 930-41

8.. Elabbadi A, Turpin M, Gerotziafas GT, Bacterial coinfection in critically ill COVID-19 patients with severe pneumonia: Infection, 2021; 49(3); 559-62

9.. Freire-Paspuel B, Garcia-Bereguiain MA, Clinical performance and analytical sensitivity of three SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid diagnostic tests: Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2021; 104(4); 1516-18

10.. Purty S, Saranathan R, Prashanth K: Emerg Microbes Infect, 2013; 2(10); e71 [Erratum: Emerg Microbes Infect. 2013;2(12):e91]

11.. , Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI): Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 2020(CLSI Suppl M100)

12.. Nudelman BG, Ouellette T, Nguyen KQ: Cureus, 2022; 14(9); 28870

13.. Lee MK, Choi SH, Ryu DW: BMC Infect Dis, 2013; 13; 475

14.. Haddadin Y, Annamaraju P, Regunath H, Central line associated blood stream infections: StatPearls [Internet] Nov 26, 2022, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing

15.. Fattorini L, Creti R, Palma C, Pantosti A, Bacterial coinfections in COVID-19: An underestimated adversary: Ann Ist Super Sanita, 2020; 56(3); 359-64

16.. Dudeja M, Tewari R, Das AK, Nandy S: J Clin Diagnostic Res, 2013; 7(8); 1692-93

17.. Páez TP, Parra GG, Bastidas AR: Pneumologia, 2019; 68(1); 37-40

18.. Dotis J, Printza N, Papachristou F: Perit Dial Int, 2012; 32(5); 577-78

19.. Savini V, Catavitello C, Masciarelli G, Drug sensitivity and clinical impact of members of the genus Kocuria: J Med Microbiol, 2010; 59(12); 1395-402

Figures

In Press

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943687

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943070

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943370

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943803

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250