08 September 2023: Articles

Complications of Transcatheter Arterial Chemoembolization for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Case Report of Bronchobiliary Fistula Development in a 68-Year-Old Man

Unusual or unexpected effect of treatment, Diagnostic / therapeutic accidents

Ta-Kai Fang1ABCDEF, Yung-Ning Huang1ABCDEF, Tung-Ying ChiangDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.939195

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e939195

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Bronchobiliary fistulas (BBFs) are abnormal communications between the biliary tract and bronchial tree. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) is a widely employed treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). While TACE is generally considered safe, there have been reports of severe complications. This case report is about a 68-year-old man who developed a BBF 6 months after undergoing TACE for HCC.

CASE REPORT: A 68-year-old man was diagnosed with HCC and underwent TACE at a local medical department. Two months after TACE, he presented with a liver abscess, which was drained and catheterized. Subsequently, the patient was transferred to our hospital. Initial MRI revealed abscesses in the right hepatic lobe extending into the lung cavity. Intrahepatic catheter replacement was performed. Six months after TACE, the patient developed cough and yellow sputum. Subsequent MRI confirmed smaller lung and liver abscesses, along with a BBF. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and percutaneous catheter replacement were conducted, closing the BBF with a covered stent. Despite drainage, antibiotics, and nutritional support, the patient’s condition deteriorated. Transition to hospice care was initiated, and the patient died due to sepsis and multiple organ failure.

CONCLUSIONS: This case highlights the importance of obtaining a comprehensive patient history when a patient has bile in the sputum, and discusses the rare but previously reported BBF as a complication of TACE for HCC. The presence of bile collections in the lungs and liver can result in tissue necrosis, potentially leading to chronic infection, emphasizing the need for early diagnosis and management.

Keywords: Biliary Fistula, Bronchial Fistula, Carcinoma, Hepatocellular, Chemoembolization, Therapeutic, Male, Humans, Aged, Liver Neoplasms

Background

Bronchobiliary fistula (BBF) is a rare condition that involves abnormal communication between the biliary tract and the bronchial tree [1]. Most BBFs are congenital disorders or complications of hydatid disease; only a few reports have discussed BBFs as complications of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [2]. Cancer is the leading cause of BBF. This may be related to the severe inflammation of the primary lesion, and, at the same time, compression by the tumor leads to narrowing of the bile duct [3]. HCC is a common malignant disease of the liver and is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [4]. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) is a well-established treatment technique for advanced HCC [5]. Although TACE is considered to be safe, numerous studies have reported TACE-related complications, such as postembolization syndrome, acute cholecystitis, pulmonary embolisms, hepatic abscesses, and bile duct injury [6]. This report is of a 68-year-old man who developed a BBF 6 months after undergoing TACE for HCC.

Case Report

A 68-year-old male patient initially underwent a whole-body positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scan, which showed 1 lesion located at the S8 segment of the liver, with the diagnosis of HCC. Subsequently, he underwent TACE at the local medical department. A follow-up laboratory examination revealed elevated bilirubin and abdominal computed tomography (CT) indicated a malignant biliary stricture. To address the biliary obstruction and hilar stenosis, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed, and a plastic stent was placed.

One month before admission to our hospital (2 months after TACE), the patient presented with fever and weakness, and an abdominal CT scan revealed the formation of a liver abscess at the primary tumor site. Ultrasound-guided drainage and pigtail catheter placement were performed at the local medical department. However, as the patient’s condition did not improve, he was transferred to our hospital.

Upon admission, the patient exhibited clinical signs of sepsis: body temperature was 38.1°C, pulse was 112 beats/min; respiration was 20/min, and blood pressure was 110/59 mmHg. A pigtail catheter was seen in the upper right abdomen. Physical examinations indicate the abdomen was soft and non-tender, with audible bowel sounds. Mild edema was present in both lower extremities. His ECOG performance status was 3.

At the time of admission, the patient’s laboratory test results revealed the AFP level was 0.97ng/mL, with an elevated white blood cell count of 14 000 with a segment neutrophil percentage of 81.3%. Additionally, the levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (Hs-CRP), lactate, and procalcitonin were 49.3 mg/L, 2.6 mmol/L, and 0.17 ng/L, respectively. These findings, along with the patient’s clinical signs, raised the suspicion of sepsis. Further investigations, including an upper-abdominal MRI, revealed multiple liver abscesses in the right hepatic lobe, with the largest abscess measuring 7.2×5.4×5.9 cm in the S8 segment. This abscess extended into the lung cavity, resulting in formation of a lung abscess in the right lower lobe and the accumulation of pleural effusion (Figure 1). The MRI also revealed moderate intrahepatic bile duct dilation, hilar biloma, and viable portal vein tumor thrombus, but no signs of intrahepatic HCC.

Given the severity of the abscess and clinal suspicion of sepsis, appropriate management was initiated. The patient received antibiotics (Meropenem, 1 g Q8H) to target the infection, and symptomatic treatments were also provided to alleviate the patient’s symptoms. Considering the moderate intrahepatic bile duct dilation and hilar biloma observed on the MRI, retrograde biliary infection of the hepatic ablation zone and impaired catheter function for abscess and biliary tract drainage was suspected. To address the large liver abscess, an intrahepatic catheter replacement was performed under percutaneous guidewire guidance along with an additional pigtail catheter in the lung cavity for drainage. Pus collected during the catheter replacement was subjected to culture, which revealed extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) production by

Subsequent follow-up imaging showed a reduction in size of the liver abscess, and the patient’s clinical condition improved. He was discharged from the hospital and advised to undergo systemic anticancer therapy, including targeted therapy, after complete resolution of the infection.

However, 3 months later (6 months after TACE), he presented with an intermittent cough and yellow sputum. Imaging, including MRI, revealed smaller lung and liver abscesses, stable viable portal vein tumor thrombus, and the development of a bronchobiliary fistula (BBF). ERCP was performed for hilar stent change and routine percutaneous catheter replacement. The cholangiography revealed the resolution of the contrast extravasation from the biliary system (S8 of the liver) to the bronchial system (right lung lobe; Figure 2). During bronchoscopy, the BBF was identified, and bile was gushing from the right lower segment of the bronchial tree (Figure 3). The BBF was closed through endoscopic implantation of a covered stent.

Despite multiple interventional drainage sessions, long-term antibiotic treatment, and nutritional support, the patient’s condition continued to deteriorate. Months later, he transitioned to hospice care and ultimately died due to sepsis and multiple organ failure. Figure 4 illustrates the chronological order of the patient’s disease and progression.

Discussion

The unfavorable outcome in the present case study demonstrates that although TACE is generally considered a minimally invasive and effective approach to treating liver cancer, healthcare providers must attentively monitor patients who undergo TACE for potential postoperative complications that may lead to adverse outcomes. BBFs are characterized by abnormal communication between the biliary and bronchial systems [1]. Most reported BBFs are congenital disorders or complications of hydatid disease. Some reports have also mentioned that BBFs may result from iatrogenic or postoperative complications, such as those associated with RFA or hepatobiliary surgery [2]. RFA-induced thermal injury is the most common type of diaphragmatic injury and the most common etiology of BBFs after liver cancer treatments [2]. Herein, we presented a rare case of a BBF following TACE. To the best of our knowledge, few cases of BBF following TACE for liver cancer have been reported.

The most common hypothesis regarding the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the formation of BBFs involves an elevation of the biliary system pressure, which may be caused by mechanical obstruction of the biliary tract due to intragenic injury; this elevated pressure produces an inflammatory reaction in the subdiaphragmatic space and subsequent rupture into the bronchial tree [7] after locally aggressive processes, such as tumor infiltration or liver dome abscess rupture through the diaphragm [2]. Pleural effusion and atelectasis may play another role in bacterial transmission for this location in liver patients. In our patient’s case, the mechanism underlying the formation of the BBF is consistent with the aforementioned hypothesis because the hilar biliary stricture and biloma increased the biliary tract pressure, inducing an inflammatory response, producing an abscess in the subdiaphragmatic area, and driving bile and pus into the lung cavity via the injured diaphragm. Rupture of the S8 segment liver abscess might have led to the subphrenic abscess and consequent injury to the diaphragm.

Liver abscess formation is a rare but severe complication of TACE. The mortality rates of patients with TACE-induced liver abscesses reported in previous studies have been high, ranging from 13.3% to 50% [8,9]. Most liver abscesses are caused by biliary injury after TACE. In our case, a liver abscess and a BBF were observed in multiple radiological image examinations.

BBFs are diagnosed based on clinical suspicion and radiological examinations. The typical symptoms of BBFs include an intermittent cough with yellowish sputum. Laboratory analysis of the sputum of patients with BBFs often reveals a bile component. ERCP and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) are used to determine the exact anatomy of a fistula. Chest and upper-abdominal CT or MRI with enhancement may be required to determine the precise location of the fistula and surrounding lesions. The identification of the underlying fistula is useful for optimizing the treatment strategy, which may involve either resection of the fistula or endoscopic embolization with minimally invasive techniques [10]. BBF management strategies may include antibiotics, systemic supportive care, and surgical or nonsurgical (PTC or ERCP) treatments. Surgical treatment is common but is associated with high rates of morbidity (14.3%) and mortality (12.7%) [11]. Nonsurgical management strategies for BBFs include percutaneous drainage or placement of a biliary drain or stent during ERCP to relieve the intrahepatic biliary trace pressure by draining the bile. Such techniques are less invasive than surgery and can provide favorable results with a lower risk of morbidity [11]. In our case, surgical resection was contraindicated because the patient’s ECOG performance status was poor, and drainage was performed using PTC and ERCP. After the patient’s condition improved, we performed a bronchoscopy and attempted endoscopic embolization. However, the procedure failed because of the unobserved intrabronchial opening of the BBF.

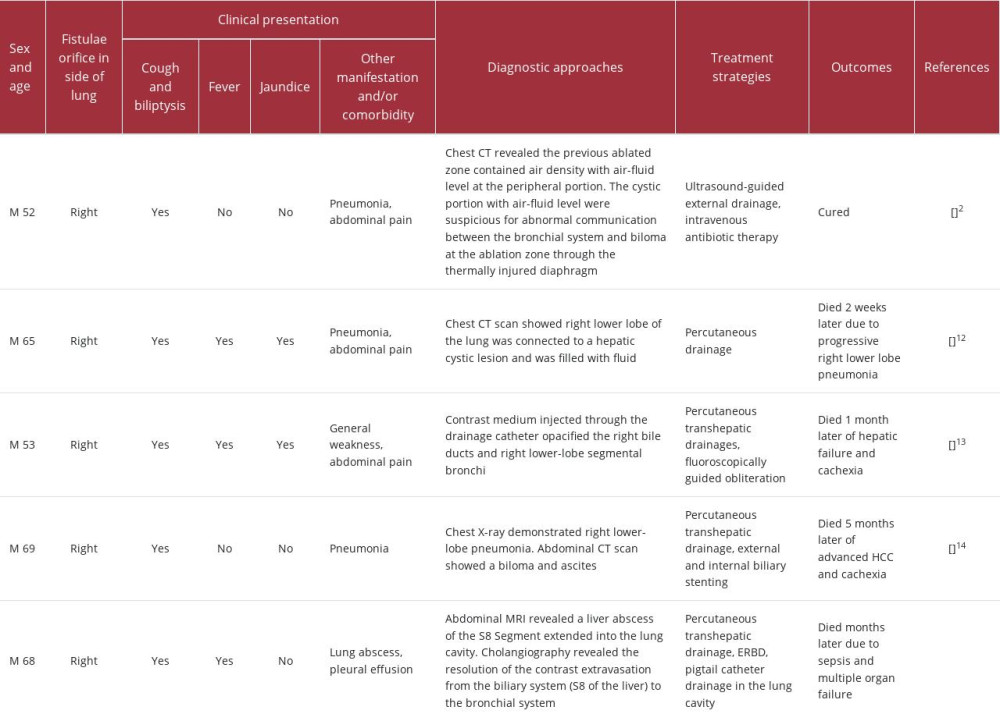

In comparison to the case mentioned in the background section [2], our patient experienced a similar occurrence of bronchobiliary fistula (BBF) following treatment for a liver tumor, whether it was through TACE or radiofrequency ablation (RFA). Both cases involved the placement of catheters for drainage. However, unlike our patient, who unfortunately died due to cachexia and infection despite external and internal drainage, the previously mentioned case had relief of symptoms and controlled infection. Furthermore, when comparing our patient’s case with previously published case reports [12–14], a similarity arises in that all patients including our patient died due to cachexia and infection after TACE. However, there are notable differences. In some of the previously reported cases, HCC had progressed, while in our patient, multiple MRI examinations did not reveal tumor recurrence, and the portal vein tumor thrombus remained stable. We compared these case report in terms of clinical presentation, diagnostic approaches, treatment strategies, and outcomes (Table 1). These distinctions highlight the significance of BBF as a complication with a high fatality rate, emphasizing the importance of proactive measures to prevent its occurrence, particularly in cases where tumors are located close to the top of the diaphragm.

According to the updated Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) guidelines, advanced-stage HCC is characterized by the presence of portal vein invasion. Numerous systemic treatments, including targeted therapies and immunotherapies, are available for patients with advanced-stage HCC. The BCLC guidelines indicate that the median expected survival time of patients with advanced-stage HCC should be over 2 years [5]. However, most of the therapies listed in the guidelines are only recommended for patients with ECOG performance status (PS) of 1 to 2; a higher PS score contraindicates systemic therapy. In our case, the patient had advanced-stage HCC with portal vein tumor thrombus, and although his liver function was preserved, his ECOG PS of 3 and comorbidity were contraindications for systemic therapy. Even if the portal vein tumor thrombus was stable without anticancer treatments from the patient’s initial admission until the final MRI examination before the patient, the duration of the patient’s survival was much shorter than the median survival duration because of the complications associated with TACE.

Conclusions

BBFs are rare complications that are associated with high mortality and morbidity rates. The present report describes a case of liver and lung abscesses with a BBF occurring months after TACE. To the best of our knowledge, only a few reports of this condition have been published. This report emphasizes the significance of obtaining a thorough history of patients presenting with bile in the sputum. BBF is a rare but previously reported complication of TACE. Bile collections in the lungs and liver cause tissue necrosis that can lead to chronic infection. These observations underscore the critical importance of early detection and proactive management strategies for improved patient outcomes.

Figures

References:

1.. Johnson MM, Chin R, Haponik EF, Thoracobiliary fistula: South Med J, 1996; 89(3); 335-39

2.. Kim Y-S, Rhim H, Sung JH, Bronchobiliary fistula after radiofrequency thermal ablation of hepatic tumor: J Vasc Interv Radiol, 2005; 16(3); 407-10

3.. Liao G-Q, Wang H, Zhu G-Y, Management of acquired bronchobiliary fistula: A systematic literature review of 68 cases published in 30 years: World J Gastroenterol, 2011; 17(33); 3842

4.. Yang JD, Roberts LR, Epidemiology and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: Infect Dis Clin North AM, 2010; 24(4); 899-919

5.. Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update: J Hepatol, 2022; 76(3); 681-93

6.. Tu J, Jia Z, Ying X, The incidence and outcome of major complication following conventional TAE/TACE for hepatocellular carcinoma: Medicine, 2016; 95(49); e5606

7.. Ferguson TB, Burford TH, Pleurobiliary and bronchobiliary fistulas: Surgical management: Arch Surg, 1967; 95(3); 380-86

8.. Lv W-F, Lu D, He Y-S, Liver abscess formation following transarterial chemoembolization: Clinical features, risk factors, bacteria spectrum, and percutaneous catheter drainage: Medicine, 2016; 95(17); e3503

9.. Huang S-F, Ko C-W, Chang C-S, Chen G-H, Liver abscess formation after transarterial chemoembolization for malignant hepatic tumor: Hepatogastroenterology, 2003; 50(52); 1115-18

10.. Wang C, Yang Z, Xia J, Bronchobiliary fistula after multiple transcatheter arterial chemoembolizations for hepatocellular carcinoma: A case report: Mol Clin Oncol, 2018; 8(4); 600-2

11.. Kabiri H, Chafik A, Al Aziz S, El Maslout A, Benosman A, [Treatment of hydatid bilio-bronchial and bilio-pleuro-bronchial fistulas by thoracotomy.]: Ann Chir, 2000; 125(7); 954-59 [in French]

12.. Lo Y-C, Hsu P-W, Chew F-Y, Chen H-Y, Special presentation of bronchobiliary fistula after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization: A case report: Medicine, 2022; 101(46); e31596

13.. Kim HY, Kwon SH, Oh JH, Percutaneous transhepatic embolization of a bronchobiliary fistula developing secondary to a biloma after conventional transarterial chemoembolization in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma: Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol, 2016; 39; 628-31

14.. Akazawa S, Omagari K, Amenomori M, Bronchobiliary fistula associated with intrahepatic biloma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: J Hepatol, 2004; 40(6); 1045-46

Figures

In Press

28 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942881

28 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943590

29 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943843

30 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943577

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250