14 May 2023: Articles

Optic Neuritis Related to Chronic Sphenoid Sinusitis as an Uncommon Cause of Vision Loss: A Case Report and Literature Review

Mistake in diagnosis, Rare disease

Barbara Nowacka1ABCDEF, Wojciech Lubiński1ABCDEF*, Jakub Lubiński2BDDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.939267

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e939267

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Optic neuritis is a rare but possible complication of sphenoid sinusitis.

CASE REPORT: We present a case of a young woman with recurrent optic neuritis associated with chronic sphenoid sinusitis. A 29-year-old woman with visual impairment of the left eye to Snellen distance best-corrected visual acuity (DBCVA) of 0.5 and migraine headaches accompanied by vomiting and dizziness reported to the ophthalmic emergency room. The preliminary diagnosis was demyelinating optic neuritis. On head computed tomography, a polypoid lesion of the sphenoid sinus was found and qualified for elective endoscopic treatment. During a 4-year follow-up, evaluation of DBCVA, fundus appearance, visual field, ganglion cells layer (GCL), peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness, and ganglion cells and visual pathway function (pattern electroretinogram – PERG, pattern visual evoked potentials – PVEPs) were performed. Four years after the occurrence of the initial symptoms, surgical drainage of the sphenoid sinus was performed, which revealed a chronic inflammatory infiltrate and a sinus wall defect on the left side around the entrance to the visual canal. After surgery, headaches and other neurological symptoms resolved, but DBCVA deteriorated in the left eye to finger counting/hand motion, partial atrophy of the optic nerve developed, the visual field defect progressed to 20 central degrees, GCL and RNFL atrophy appeared, and deterioration of ganglion cells and visual pathway function were observed.

CONCLUSIONS: In patients with optic neuritis and atypical headaches, sphenoid sinusitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Delayed laryngological intervention can cause irreversible damage to the optic nerve.

Keywords: Headache, optic neuritis, Sphenoid Sinusitis, Female, Humans, Adult, Evoked Potentials, Visual, Vision Disorders, Chronic Disease, Tomography, Optical Coherence, Atrophy

Background

Optic neuritis related to chronic sphenoid sinusitis is an uncommon but a possible cause of vision loss due to the anatomical proximity of the optic nerve to the sphenoid sinus. The mechanisms of optic nerve damage include direct spread of infection, occlusive vasculitis, and osteomyelitis of the sinus wall secondary to chronic inflammation [1]. Optic neuritis as a result of sphenoid sinusitis should be considered in patients with clinical features of optic neuritis associated with atypical symptoms, including headache, nausea/vomiting, dizziness, fever, ophthalmoplegia, and deterioration of vision beyond 2 weeks, as well as with the history of sinus disease [2]. We present a case report of a young woman with recurrent optic neuritis associated with chronic sphenoid sinusitis and provide a literature review.

Case Report

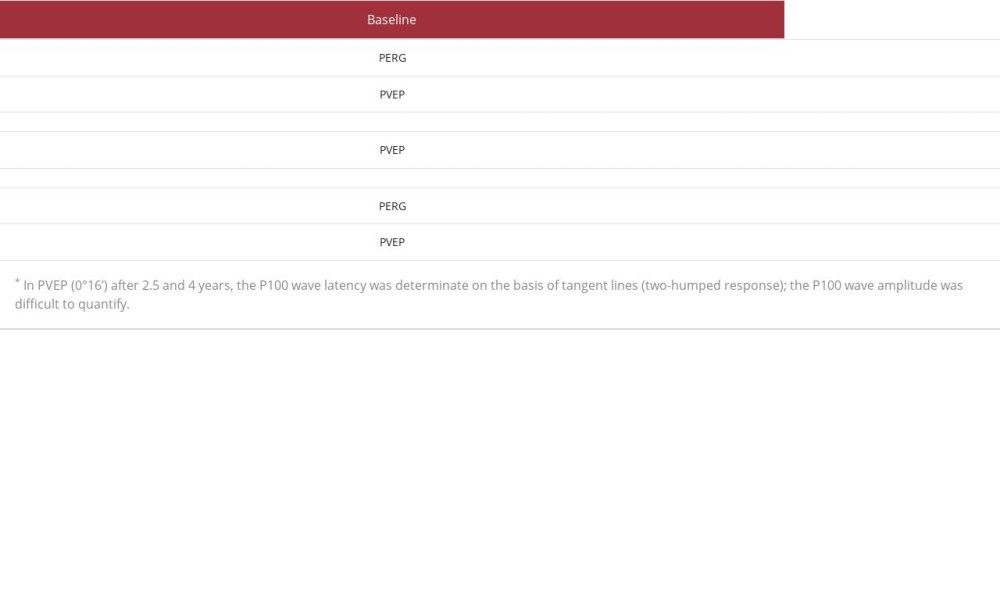

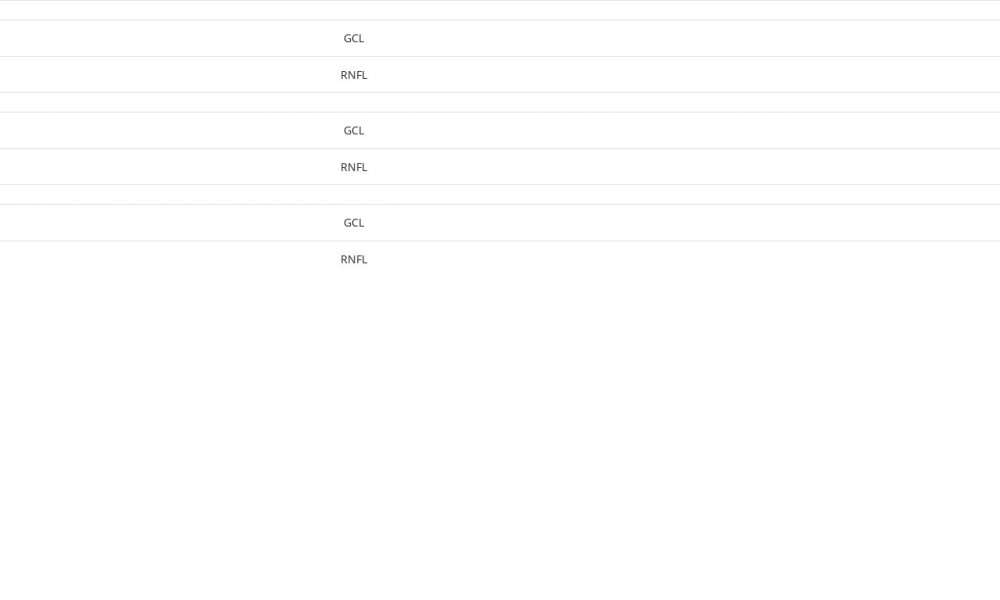

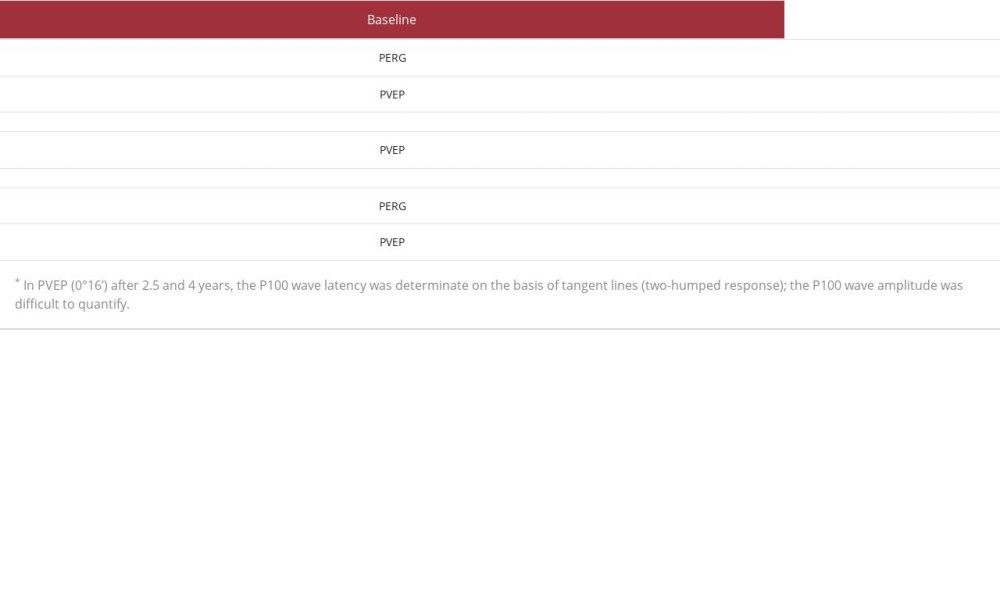

A 29-year-old woman reported to the clinical ophthalmic emergency room suspected to have demyelinating optic neuritis (ON) in her left eye. She reported having a visual field defect, recurrent dizziness, nausea, and frequent migraine headaches accompanied by vomiting for about 2 months. She said she was under neurological supervision for her headaches and was being treated with analgesics. The ophthalmological examination revealed: Snellen distance best-corrected visual acuity (DBCVA) of 1.0 in her right eye and 0.5 in her left eye, normal intraocular pressure in both eyes, normal pupil reactions, but slight relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) in the left eye, and normal anterior segment of both eyes and fundus of the right eye; however, the optic disc was slightly elevated with marked borders of the left eye (Figure 1). On static perimetry (Zeiss, HFA 24-2 W-W), upper arcuate scotoma in the left eye was observed (Table 1). Pattern electroretinogram (PERG, ISCEV Standard 2013 [3]) revealed slightly reduced amplitudes of P50 and N95 waves, while pattern visual evoked potentials (PVEPs, ISCEV Standard 2016 [4]) showed increased latencies of P100 waves for large (1°4’) and small (0°16’) checkerboards (Table 2) in the left eye. Electrophysiological examination findings regarding the right eye were normal. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed no ischemic or demyelinating lesions, and no pathological enhancement, but there was shadowing within the sphenoid sinus. Due to the revealed opacity, the patient was referred to laryngological consultation. On head computed tomography (CT), a polypoid lesion of the sphenoid sinus was identified and qualified for elective endoscopic treatment. The following day, the patient reported to the emergency room in another hospital due to a further decrease in DBCVA down to 0.3 in the left eye and dilated pupils non-responsive to light. She was referred for further neurological diagnostics with the suspicion of demyelinating ON. Physical examination did not provide evidence of neurological dysfunction. The was no history of multiple sclerosis in the patient’s family. The lumbar puncture was performed but oligoclonal bands were not detected. Also, MRI of the head and spine showed no demyelinating changes characteristic of multiple sclerosis. After a few days, the patient reported an improvement in DBVCA to 0.6 in her left eye and normal pupil responses. After 6 months, the patient came to our neuro-ophthalmological outpatient clinic. Distance best-corrected visual acuity was 1.0 in her left eye. On ophthalmological examination, the following abnormalities were revealed: slightly elevated and paler optic disc in the left eye with no cupping (cup-to-disc ratio of 0.2 in her right eye) and ganglion cell layer (GCL) reduction in the left eye on SD-OCT (Table 3). Due to persistent symptoms such as headache, tinnitus, dizziness and nausea, the patient was referred again to a neurologist to exclude intracranial hypertension, but she did not report for the visit, initially explaining that the headaches resolved on their own after stress reduction, but eventually admitted that she was afraid of another lumbar puncture. In the meantime, she reported to different ophthalmic emergency rooms several times due to DBCVA deterioration down to 0.4–0.5 in her left eye. Episodes of recurrent demyelinating optic neuritis were re-suspected. The patient came once again to neuro-ophthalmological outpatient clinic after 2.5 years. The ophthalmological examination revealed the following abnormalities in the left eye: DBCVA=0.5, fundus appearance as at the baseline, reduction in GCL and borderline RNFL on SD-OCT (Table 3) and prolongation of P100 wave latency on PVEPs (Table 2) (PERG was not performed). Findings regarding the right eye were normal. Brain MRI revealed a small amount of mucous content in the sphenoid sinus, and increased fluid signal in the left optic nerve with a slight reduction in its thickness compared to the right side, possibly chronic demyelinating changes (Figure 2). The patient was referred to a neurologist again for further diagnosis. In the meantime, 4 years after the occurrence of the initial symptoms, elective surgical drainage of the sphenoid sinus (Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery – FESS) was performed, which revealed chronic inflammatory infiltrate and a sinus wall defect on the left side averaging 1–2 mm around the entrance to the visual canal (not present on the previous CT scan) (Figure 3). The cytology of the drainage was sterile, and the histopathological examination revealed fragments of the mucous membrane with chronic inflammation. There were no other complications of sphenoid sinusitis, including cavernous sinus thrombosis. After the surgery, her headaches and other neurological symptoms resolved, but DBCVA deteriorated in the left eye to finger counting/hand motion, partial atrophy of the optic nerve developed, the visual field defect had progressed to 20 central degrees on static perimetry 24-2 W-W (Table 1), GCL and RNFL atrophy appeared (Table 3), and deterioration of ganglion cells and visual pathway function were observed (Table 2), probably as a result of optic nerve damage by recurrent inflammation and/or iatrogenic injury possible by osteomyelitis of the sinus wall. Findings regarding the right eye remained normal. To date (nearly 6 years after the first symptoms), the patient remains under the care of a neurologist and further neurological examination and MRI are being performed, but she still does not meet the criteria for the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis.

Discussion

Optic neuritis is an acute inflammatory disorder of the optic nerve that is clinically manifested by a temporary but severe unilateral visual loss. In a typical case, impaired color vision, visual field defects and a relative afferent pupillary defect can also be observed in the affected eye. In approximately 90% of all cases, the patients have pain, particularly during eyeball movements, for about 3–5 days. Vision recovery lasts over the subsequent 3–6 weeks [5,6]. Optic neuritis may be a complication of many diseases. The most common is demyelination secondary to multiple sclerosis or neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders [5,6]. However, optic neuritis has also been reported in association with hypertension and hyperthyroidism [7], infectious diseases such as rubella, mumps, measles and mononucleosis [8], systemic neoplasia [9], lead, arsenic, and methanol poisoning [7,10], and paranasal sinus diseases [1,2,11,12]. Because of the anatomical proximity of the optic canal to the sphenoid sinus, the optic nerve is vulnerable to the direct spread of infection or inflammation from the latter [1]. A cadaveric study revealed a dehiscent bony wall of the optic canal in 6% of patients, and the defect measure was as little as 0.1 mm in some cases [13]. Moreover, in rare cases, the optic nerve may pass through the lumen of the sphenoid sinus in some part of its course [13]. Beyond direct spread, the mechanisms of optic nerve damage due to sinusitis include occlusive vasculitis and bone loss in the sinus wall [1]. Acute isolated sphenoid sinusitis occurs in 3–7% of cases of all paranasal sinus infections [14,15]. The most common sign of ON related to sphenoid sinusitis is headache, which can be retrobulbar (different from discomfort acceptable as a feature of demyelinating ON), parietal, or frontal. In addition, systemic symptoms such as nausea/vomiting, dizziness, fever, or ophthalmoplegia may be reported [1,16]. The pathological diagnosis usually involves bacterial infection, but it may also be fungal infections such as aspergillosis, sinus tumor, or polyps [1,16].

In the presented case, we observed osteomyelitis of the sinus wall secondary to chronic inflammation caused by a polyp. Beyond decreased visual acuity, the most prominent symptom was headaches. The symptoms recurred despite the lack of conservative laryngological treatment of chronic sphenoid sinusitis, but during the exacerbation of the disease, she was taking oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that could temporarily reduce the inflammation to some extent. In the beginning, the optic disc was elevated with normal average RNFL thickness on OCT. However, with subsequent attacks of inflammation, we observed progressive RNFL reduction in the affected eye, which suggested degeneration of the optic nerve fibers. After surgical drainage, the patient reported having occasional slight headaches, but neuropathy of the left optic nerve resulted in permanent vision loss. A causal relationship between sphenoid sinusitis and optic neuritis has been reported several times in the available literature. Moorman et al [1] described 10 cases of acute optic neuritis with isolated opacity of the sphenoid sinus. The underlying disease ranged from sinus infection to polyp and tumor, but all patients reported accompanying atypical headaches. It is worth noting that episodes of optic neuritis were recurrent over a couple of years, as in the presented case. The ophthalmological examination revealed normal or swollen optic disc appearance, besides 1 case where it was pale. Patients were treated with surgical drainage and broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics. Most patients recovered their normal vision after treatment. In patients with permanent vision loss, osteomyelitis of the sphenoid sinus wall was observed in 1 case, widespread aspergillosis that extended posteriorly to the cavernous sinus in another case, and invasive squamous cell carcinoma in yet another. These findings suggest the importance of initiating treatment when sinus walls are still intact to preserve vision. Gallagher et al [11] described 2 cases of optic neuropathy related to sinus disease. In the first, a 36-year-old man had a 3-day history of worsening vision and headache. He was taking oral antibiotics for a “sinus infection” without symptomatic improvement. The optic nerve head of the affected eye appeared normal. Computed tomography showed opacification of the sphenoid and ethmoid sinuses. The patient declined exploratory sinus surgery, so he was treated with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid at 500/125 mg orally 3×daily, clarithromycin at 500 mg orally 2×daily, betamethasone at 0.1% w/v, 2 drops nasally, 3×daily, fluticasone at 100 µg nasally daily and saline nasal rinses 2×daily with the improvement of visual acuity to normal level within 3 days. The second case was a 20-year-old man with a 3-month history of blurred vision in one eye. He was lethargic, felt nauseous, and had been vomiting. On examination, visual acuity of the affected eye decreased to light perception, and the optic nerve was grey with the neuroretinal rim almost completely absent. Polyps were noted on nasendoscopy, and computed tomography identified an extensive paranasal sinus disease causing osteomyelitis of the sphenoid sinus wall and involving the orbital apex and the chiasm on the affected side. The patient underwent endoscopic sinus surgery 3 times, which confirmed aspergillosis, and was treated with antibiotics intravenously: vancomycin at 15 mg/kg 2×daily, cefotaxime 2 g 6×daily, amphotericin B at 0.5 mg/kg daily, and metronidazole at 7.5 mg/kg 2×daily. As a maintenance treatment, he received oral voriconazole 400 mg 2×daily for 12 months. He did not recover vision in the affected eye, which made him yet another case where the destruction of the sphenoid sinus bone led to permanent loss of vision. Two other cases of optic neuritis secondary to sphenoid sinusitis were reported by Chafale et al [2]. The first case was a 65-year-old woman a 3-month history of progressive visual impairment in the right eye and after 2 months from the beginning of the symptoms also in the left eye. Visual acuity was at the level of finger counting at 3 feet in the right eye and 6/36 in the left eye. The optic nerve heads appeared normal in both eyes, but VEPs showed increased latency and reduced amplitudes on both sides, more prominent on the right side. A review of history revealed a breast carcinoma 3 years ago, while MRI led to the diagnosis of metastases with direct compression and infiltration of the optic nerves. The second case was a 65-year-old female with acute visual loss to light perception in the left eye for to 2 months and left-sided frontal headache. The fundus was normal in both eyes, but VEPs showed absent response on the left side. Radiological imaging revealed optic neuropathy caused by an isolated mucocele in a sphenoethmoidal air cell, commonly known as the Onodi air cell. The patient did not agree to rhinological surgery and was treated conservatively with antibiotics, mucolytics, and decongestants. Vision improved only to the level of finger counting at 3 feet after a month of follow-up. The Onodi air cell is an anatomical variant of the paranasal sinuses. It is the most posterior ethmoid air cell that lies superolateral to the sphenoid sinus. It is important due to closely associated structures: the optic nerve and internal carotid artery [17]. As in the last presented case, mucocele in the Onodi air cell was shown as a cause of optic neuropathy several times; it was mostly reversible when treated with prompt surgical drainage in the acute phase [18–20].

Conclusions

In patients with loss of vision due to atypical ON, isolated opacity of the sphenoid sinus should not be overlooked and should be considered an otolaryngological emergency. With immediate proper conservative treatment or surgical drainage, if necessary, ON associated with sphenoid sinusitis can be reversible, but delay in diagnosis and inappropriate treatment, such as with steroids, leads to permanent impairment of vision.

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Progression of static perimetry scotoma of the left eye of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up. Table 2.. Evaluation of pattern electroretinogram (PERG) and visual evoked potentials (PVEP) in the left eye of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up.

Table 2.. Evaluation of pattern electroretinogram (PERG) and visual evoked potentials (PVEP) in the left eye of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up. Table 3.. Evaluation of ganglion cell layer (GCL) and retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) in optical coherence tomography (OCT) of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up.

Table 3.. Evaluation of ganglion cell layer (GCL) and retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) in optical coherence tomography (OCT) of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up.

References:

1.. Moorman CM, Anslow P, Elston JS, Is sphenoid sinus opacity significant in patients with optic neuritis?: Eye, 1999; 13; 76-82

2.. Chafale VA, Lahoti SA, Pandit A, Retrobulbar optic neuropathy secondary to isolated sphenoid sinus disease: J Neurosci Rural Pract, 2015; 6; 238-40

3.. Bach M, Brigell MG, Hawlina M, ISCEV standard for clinical pattern electroretinography (PERG) – 2012 update: Doc Ophthalmol, 2013; 126; 1-7

4.. Odom JV, Bach M, Brigell M, ISCEV standard for clinical visual evoked potentials – (2016 update): Doc Ophthalmol, 2016; 133; 1-9

5.. , Experience of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Optic Neuritis Study Group: Arch Ophthalmol, 1991; 109; 1673-78

6.. Ormerod IE, McDonald WI, du Boulay GH, Disseminated lesions at presentation in patients with optic neuritis: J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 1986; 49; 124-27

7.. Rothstein J, Maisel RH, Berlinger NT, Wirtschafter JD, Relationship of optic neuritis to disease of the paranasal sinuses: Laryngoscope, 1984; 94; 1501-8

8.. Selbst RG, Selhorst JB, Harbison JW, Myer EC, Parainfectious optic neuritis. Report and review following varicella: Arch Neurol, 1983; 40; 347-50

9.. Boghen D, Sebag M, Michaud J, Paraneoplastic optic neuritis and encephalomyelitis. Report of a case: Arch Neurol, 1988; 45; 353-56

10.. Naeser P, Optic nerve involvement in a case of methanol poisoning: Br J Ophthalmol, 1988; 72; 778-81

11.. Gallagher D, Quigley C, Lyons C, McElnea E, Fulcher T, Optic neuropathy and sinus disease: J Med Cases, 2018; 9; 11-15

12.. Kim YH, Kim J, Kang MG, Optic nerve changes in chronic sinusitis patients: Correlation with disease severity and relevant sinus location: PLoS One, 2018; 13; e0199875

13.. Yeoh KH, Tan KK, The optic nerve in the posterior ethmoid in Asians: Acta Otolaryngol, 1994; 114; 329-36

14.. Deans JA, Welch AR, Acute isolated sphenoid sinusitis: A disease with complications: J Laryngol Otol, 1991; 105; 1072-74

15.. Digre KB, Maxner CE, Crawford S, Yuh WT, Significance of CT and MR findings in sphenoid sinus disease: Am J Neuroradiol, 1989; 10; 603-6

16.. Hadar T, Yaniv E, Shvero J, Isolated sphenoid sinus changes-history, CT and endoscopic finding: J Laryngol Otol, 1996; 110; 850-53

17.. Gaillard F, Qaqish N, Botz B, Sphenoethmoidal air cell Reference article, [serial online] 2022 Nov 27. Available from: URL: Radiopaedia.org

18.. Klink T, Pahnke J, Hoppe F, Lieb W, Acute visual loss by an Onodi cell: Br J Ophthalmol, 2000; 84; 801-2

19.. Yoshida K, Wataya T, Yamagata S, Mucocele in an Onodi cell responsible for acute optic neuropathy: Br J Neurosurg, 2005; 19; 55-56

20.. Kitagawa K, Hayasaka S, Shimizu K, Nagaki Y, Optic neuropathy produced by a compressed mucocele in an Onodi cell: Am J Ophthalmol, 2003; 135(2); 253-54

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Progression of static perimetry scotoma of the left eye of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up.

Table 1.. Progression of static perimetry scotoma of the left eye of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up. Table 2.. Evaluation of pattern electroretinogram (PERG) and visual evoked potentials (PVEP) in the left eye of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up.

Table 2.. Evaluation of pattern electroretinogram (PERG) and visual evoked potentials (PVEP) in the left eye of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up. Table 3.. Evaluation of ganglion cell layer (GCL) and retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) in optical coherence tomography (OCT) of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up.

Table 3.. Evaluation of ganglion cell layer (GCL) and retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) in optical coherence tomography (OCT) of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up. Table 1.. Progression of static perimetry scotoma of the left eye of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up.

Table 1.. Progression of static perimetry scotoma of the left eye of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up. Table 2.. Evaluation of pattern electroretinogram (PERG) and visual evoked potentials (PVEP) in the left eye of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up.

Table 2.. Evaluation of pattern electroretinogram (PERG) and visual evoked potentials (PVEP) in the left eye of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up. Table 3.. Evaluation of ganglion cell layer (GCL) and retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) in optical coherence tomography (OCT) of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up.

Table 3.. Evaluation of ganglion cell layer (GCL) and retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) in optical coherence tomography (OCT) of a patient with optic neuritis associated with sphenoid sinus disease during 4-year follow-up. In Press

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943687

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943070

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943370

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943803

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250