09 June 2023: Articles

Cryptogenic Abdominal Pain: Recognizing False Leads

Challenging differential diagnosis, Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Amna Anees1ABCDEFF*DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.939504

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e939504

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Lead toxicity is a rare yet serious condition which can be difficult to diagnose due to vague presenting symptoms. Other pathologies can also mimic the symptoms of chronic lead toxicity, making an already difficult diagnosis more challenging. There are multiple environmental and occupational contributors to lead toxicity. A thorough history and an open differential is the key to diagnosing and treating this rare disease. With increasing diversity of our patient population, we should keep an open differential, as the epidemiological features of presenting concerns have diversified as well.

CASE REPORT: A 47-year-old woman presented with persistent nonspecific abdominal pain despite extensive prior work, surgeries and a prior diagnosis of porphyria. This patient was eventually diagnosed as having lead toxicity when her most recent work-up for abdominal pain revealed no urine porphobilinogen and a high lead level. The cause of lead toxicity was attributed to be an eye cosmetic called “Surma”, which can have variable lead levels. Chelation therapy was advised for the patient.

CONCLUSIONS: It is important to recognize the difficulty in this challenging diagnosis for nonspecific abdominal pain and to eliminate the mimickers. This case is interesting because the patient was initially diagnosed with porphyria, highlighting how heavy metals, lead in this case, can lead to a false-positive diagnosis of porphyria. Accurate diagnosis requires awareness of the role of urine porphobilinogen, checking lead levels, and an open differential. This case also emphasizes the importance of avoiding anchor bias to make a timely diagnosis of lead toxicity.

Keywords: Abdominal Pain, Lead Poisoning, Porphyrias, Female, Humans, Middle Aged, Lead, Porphobilinogen

Background

Lead poisoning is an uncommon diagnosis during hospitalizations. Lead exposure, occupational as well as environmental, occurs all over the world. Adult lead toxicity is defined as mean blood lead level (BLL) > 10 mcg/dL. Chronic lead toxicity is challenging to diagnose. It can present as fatigue, constipation, abdominal pain, irritability, myalgia, and insomnia, among other symptoms [1,2]. Overall, in the United States (US), there has been a decrease in the prevalence of elevated lead levels (BLLs ≥10 mcg/dL) from 1994 to 2016 [3]. The national prevalence rate has declined from 26.6 adults per 100 000 employed people in 2010 (among 37 states) to 15.8 in 2016 (among 26 reporting states) [4]. Due to the low incidence, it is often not considered in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting to the hospital with nonspecific symptoms, leading to unnecessary testing and delayed diagnosis. Another caveat is that other pathologies can mimic symptoms of lead toxicity, making the diagnosis more challenging [2].

Case Report

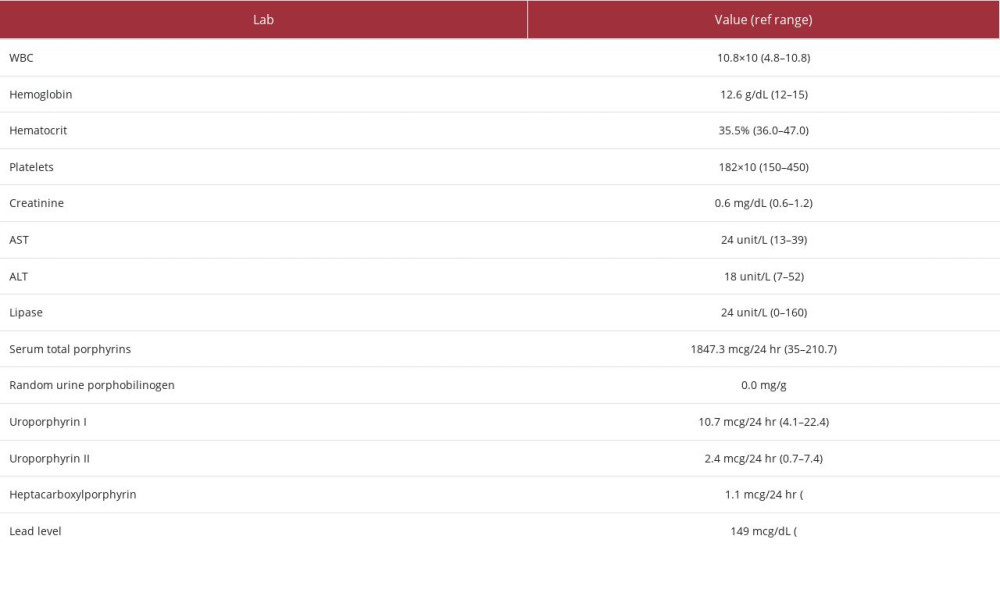

A 47-year-old woman visiting the US from Iran presented with diffuse, severe abdominal pain. It was colicky in nature. Her past medical history included hypertension and acute porphyria, diagnosed 3 years prior in Iran, and cholecystectomy. Her initial basic blood work was unremarkable (Table 1). She had an initial CT scan done in the Emergency Department (ED), which showed some thickening of the colon wall (Figure 1). She was treated for nonspecific colitis and her pain responded with medications. She tolerated an oral diet the next day and was discharged home. Unfortunately, she was readmitted 2 weeks later with the same symptoms. Her complete blood count was unremarkable and a peripheral blood smear did not show any abnormal findings. Her complete metabolic panel was also within normal limits except for mild hyponatremia (sodium 134 mEq/L). This time, she had a repeat abdomen and pelvis CT scan, which showed resolving colitis. Upper-endoscopy and colonoscopy were both negative. With no apparent cause found for her abdominal pain, the focus was shifted to her prior diagnosis of porphyria. Hematology was consulted and treatment was recommended with hemin, which she refused because of the cost. Her total porphyrin level was high. However, her urine porphobilinogen level was negative (Table 1). With this discrepancy, her lead level was checked, and was found to be 149 mg/dL. Her ALA level was not checked during her admission. The prior diagnosis of porphyria was made in Iran around 3 years before, shortly after she had her gallbladder removed because of persistent abdominal pain. She reported multiple hospital admissions with abdominal pain while in Iran during that time. After providing an extensive history to pinpoint the cause of lead toxicity, she recalled using “Surma”, an eye cosmetic with variable and sometimes unregulated ingredients, including lead. With an extremely high lead level, she was advised to be admitted to the hospital to undergo chelation therapy. However, because of the cost, she refused any further treatment. Against medical advice she travelled back to Iran and was admitted there for chelation therapy. A 3-month follow-up call was made to her closest relative living in the US, and he reported she was doing well after chelation treatment in Iran.

Discussion

Lead toxicity is a rare yet potentially serious and sometimes fatal disease, which should be kept in the differential of nonspecific and vague concerns, especially abdominal pain. Failure to make the proper diagnosis can result in multiple admissions, extensive testing, unnecessary surgeries, and a high economic burden for the patient and health care system. Occupational exposure may be easier to pinpoint, but environmental exposure is particularly difficult to identify. Sources of lead include gasoline, paint, lead-glazed cookware [5], herbal remedies, bullets, and cosmetics. Lipstick is a known source of lead. Another cosmetic used in eyes, “Surma”, also contains high levels of lead [6]. This is even more concerning as it is unregulated, with variable levels of lead and widely available worldwide [6]. In our patient, we could not ascertain another cause of lead to explain her high levels, but she admitted to having used “Surma” frequently. “Surma” is used as an eyeliner in multiple cultures as a cosmetic and to ward off “evil eye” and is used for both adults and children, including infants. It is applied to the conjunctival surface of the eye, which increases the chance of mucosal absorption, increasing the risk of lead toxicity [7].

The initial diagnosis of acute porphyria in our patient is interesting, as a false-positive urine porphyrin test is possible with heavy metal poisoning such as lead [8–10]. Unfortunately, because of her initial care in Iran, it was not possible to obtain information on how the initial diagnosis was made, but she did have recurrent abdominal pain at that time, resulting in cholecystectomy, as well as the diagnosis of acute porphyria. Lead inhibits most enzymes in the heme synthesis pathway; however, ALA dehydratase is affected the most. This results in normal porphobilinogen levels as seen in our patient despite an initial positive porphyrin test. The degree of effect on heme synthesis depends on the severity of exposure to lead. Common findings with lead toxicity include increased excretion of delta-aminolevulinic acid and coproporphyrin III in urine. [11].

A challenging component in this case is that the patient had normal hemoglobin levels and normal kidney and liver function test results. Also, having a prior diagnosis of porphyria could result in potential bias in attributing abdominal pain to porphyria and not searching for an additional source. Thus, it is very important to avoid premature closure and anchor bias, and to delve into other differentials in cases of diagnostic uncertainty [12]. It is also crucial to keep in mind that with diversifying patient populations, and patients from different backgrounds with different cultural or religious practices, it is important to obtain a good history to arrive at the correct diagnosis. Treatment of lead toxicity is largely dependent on the presence of symptoms, as well as lead levels.

Conclusions

Lead poisoning is a rare but serious cause of abdominal pain. In high-risk patients with multiple negative test results for presenting symptoms like abdominal pain and fatigue, exploring the history and checking the lead level can prove beneficial in establishing a diagnosis. Failure to diagnose and treat lead toxicity can lead to complications, as well as unnecessary diagnostic testing and healthcare expenditures.

References:

1.. Frith D, Yeung K, Thrush S, Lead poisoning – a differential diagnosis for abdominal pain: Lancet, 2005; 366(9503); 2146

2.. Young S, Chen L, Palatnick W, Led astray: N Engl J Med, 2020; 383(6); 578-83

3.. Alarcon WA, Elevated blood lead levels among employed adults – United States, 1994–2013: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2016; 63(55); 59-65

4.. , Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Available at: (accessed online on 7/28/2022)https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/lead/ables.html

5.. , Childhood lead poisoning from commercially manufactured French ceramic dinnerware – New York City, 2003: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2004; 53(26); 584-86

6.. Filella M, Martignier A, Turner A, Kohl containing lead (and other toxic elements) is widely available in Europe: Environ Res, 2020; 187; 109658

7.. Goswami K, Eye cosmetic ‘surma’: Cidden threats of lead poisoning: Indian J Clin Biochem, 2013; 28(1); 71-73

8.. Akshatha LN, Rukmini MS, Shenoy MT, Lead poisoning mimicking acute porphyria!: J Clin Diagn Res, 2014; 8(12); CD01-2

9.. McEwen J, Paterson C, Drugs and false-positive screening tests for porphyria: Br Med J, 1972; 1(5797); 421

10.. Tsai MT, Huang SY, Cheng SY, Lead poisoning can be easily misdiagnosed as acute porphyria and nonspecific abdominal pain: Case Rep Emerg Med, 2017; 2017; 9050713

11.. Lubran MM, Lead toxicity and heme biosynthesis: Ann Clin Lab Sci, 1980; 10(5); 402-13

12.. Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R, Diagnostic error in internal medicine: Arch Intern Med, 2005; 165(13); 1493-99

In Press

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943370

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943803

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943467

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943376

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250