21 July 2023: Articles

A Case of Hemorrhagic Cholecystitis in a Patient on Apixaban After COVID-19 Infection

Unknown etiology, Challenging differential diagnosis, Unusual or unexpected effect of treatment, Adverse events of drug therapy

Zohour AnouassiDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.939677

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e939677

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Hemorrhagic cholecystitis is a rare cause of abdominal pain, which can result from malignancy, bleeding, or trauma. The presentation, which includes right upper-quadrant pain, nausea, and vomiting, can overlap with other disease states, thereby rendering the diagnosis challenging.

CASE REPORT: We describe a patient taking apixaban wo had paroxysmal atrial fibrillation with history of joint pain on long-term steroids who developed hemorrhagic cholecystitis following an episode of pneumonia secondary to SARS-CoV-2 virus (COVID-19) infection. The hospital COVID-19 pneumonia protocol included the administration of steroids and symptomatic care. Following discharge, he presented to our hospital with a sudden onset of severe abdominal pain and distention accompanied by elevated liver enzymes and a low hemoglobin level of 78 g/L. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed a distended gallbladder and intraluminal layering, early subacute blood products, and increased wall thickness, which was thought to represent non-calcular hemorrhagic cholecystitis. Furthermore, a stable 18×16×20 mm cyst in the tail of the pancreas was also located posteriorly, with indentation to the splenic vein. The patient was managed conservatively, and the pain subsided on day 3 after admission.

CONCLUSIONS: Hemorrhagic cholecystitis is rarely reported with the use of the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). In our case the combination of a recent COVID-19 hospitalization, steroid use, and possible pancreatic cancer (CA 19-9 288.4 kU/L) may have contributed to such incidence in the setting of apixaban utilization; however, it is not possible to make definitive correlations. Investigating hemorrhagic cholecystitis in the setting of DOAC use in patients with multiple risk factors such as those that existed in our patient is imperative for proper diagnosis and management.

Keywords: Cholecystitis, COVID-19, Humans, Male, Abdominal Pain, Hemorrhage, Aged

Background

Hemorrhagic cholecystitis is a rare cause of abdominal pain, which can result from malignancy, bleeding, or trauma [1]. The incidence of hemorrhagic cholecystitis is estimated at 3.5% of all reported cholecystitis cases, with mortality rates of 15–20% [2]. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis in patients on apixaban is rare and limited to case reports. The presentation, which includes right upper-quadrant pain, nausea, and vomiting, can overlap with other disease states, thereby rendering the diagnosis challenging. Early diagnosis and management can reduce mortality and improve the clinical outcomes [1,3]. We present an unusual case of hemorrhagic cholecystitis after recent initiation of the direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) apixaban, as well as steroid treatment of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pneumonia in the setting of suspected pancreatic cancer.

Case Report

A 67-year-old non-smoker man, with a past medical history of lung sarcoidosis, interstitial lung disease (ILD), bronchial asthma, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, chronic kidney disease (CKD), controlled hypertension, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), was transferred from a rehabilitation center to our quaternary care hospital after a sudden onset of severe abdominal pain, distention, and jaundice for 3 consecutive days prior to hospital presentation. His vital signs on presentation were unremarkable (temperature 36.8ºC, blood pressure 109/66 mmHg, heart rate 87 bpm, respiratory rate 18). Three weeks earlier, he had been discharged on a steroid taper protocol after treatment for COVID-19 pneumonia; at which time he was also diagnosed with new-onset paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF) and started apixaban 5 mg twice daily. Anticoagulation with apixaban was continued until the morning he was admitted to our hospital. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was completed before the hospital transfer, which revealed fecal impaction.

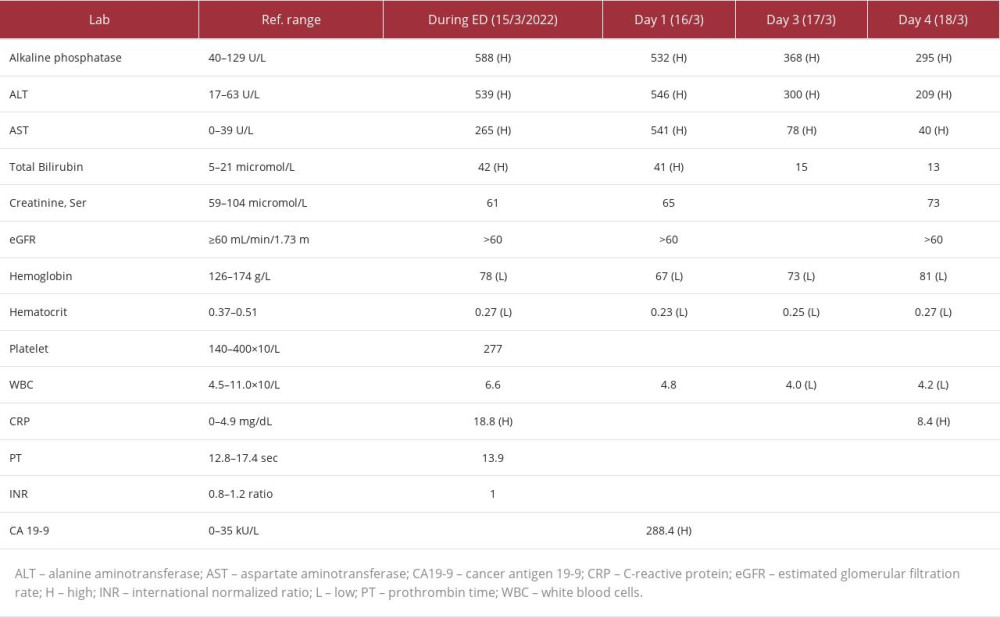

At the Emergency Department (ED) presentation, the patient described his abdominal pain as sudden-onset, severe (10/10 intensity), non-radiant, generalized in the right upper quadrant over the past 5 hours, and exacerbated by eating. He also reported having nausea and constipation, for which he was given hyoscine butylbromide, pantoprazole, and morphine intravenously. A gastroenterology examination revealed negative Murphy signs but with slight jaundice. Laboratory work revealed elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 539 U/L, an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 265 U/L, bilirubin of 42 micromole/L, alkaline phosphate (ALP) of 588, lipase 84 U/L; and a decline of hemoglobin (Hb) to 78 g/L, and a hematocrit (Hct) of 27%. At the same time, white blood cells (WBC), and international normalized ratio (INR) were within normal limits (Table 1). The patient was evaluated by the surgical team; apixaban was held and piperacillin/tazobactam was initiated. The CT of the patient’s abdomen and pelvis showed a diffusely distended hyperattenuating gallbladder (Figure 1). An ultrasound of the abdomen right upper quadrant (gallbladder, liver, and pancreas) showed non-shadowing echogenic material within the gallbladder lumen suggestive of sludge, and at that time hemorrhage and gallstones were excluded. There was no pathologic thickening or focal tenderness to suggest acute cholecystitis, although trace nonspecific pericholecystic fluid was likely present.

On day 1 of admission, in anticipation of any potential intervention, the patient was transitioned from apixaban to heparin intravenous (IV) infusion with aPTT goal of 60–85 seconds for continued stroke prevention given the patient’s high CHA2DS2-VASc score of 3 (age 65–74, hypertension, and diabetes mellites) and HASBLED score of 4 (hypertension, liver disease, age >65, on apixaban). Oral prednisolone 10 mg once daily was continued for his post-COVID-19 pneumonia sequalae. The patient was conservatively and symptomatically managed and continued to symptomatically improve in terms of nausea or vomiting, jaundice, and pain. However, on day 2 of admission, a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showed a distended gallbladder and intraluminal layering, early sub-acute blood products, and increased wall thickness, which was thought to likely represent a non-calcular hemorrhagic cholecystitis (Figures 2, 3). Furthermore, a stable 18×16×20 mm cyst in the tail of the pancreas was also located posteriorly with indentation to the splenic vein (Figure 4). Since imaging did not show gallbladder necrosis, emphysematous gallbladder, gallbladder perforation, or gallbladder stones, cholecystectomy was not pursued. Furthermore, considering his recent past medical history (sarcoidosis and prior ICU admission for COVID-19 pneumonia) and his relatively stable presentation without any signs of sepsis, no surgical intervention was pursued as part of his treatment. In addition, the patient’s laboratory parameters did not show a drop in platelets, prolonged PT, or thromboembolism symptoms to suggest disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Fibrinogen and D-dimer levels were not checked. The heparin infusion was discontinued and he was only provided with supportive care with IV fluid, pain control, electrolyte correction, prednisolone 10 mg daily, and IV antibiotic for a total of 4 days per the IDSA complicated intra-abdominal infection guideline recommendations [4].

On day 3 of admission, the patient experienced a sudden drop in Hb, from 78 to 67 g/L in 8 hours. He received 1 unit of packed RBC and Hb increased to 73 g/L. The surgery team reevaluated the case and decided to manage conservatively given the lack of pain or other symptoms to indicate acute cholecystitis like cholelithiasis, particularly since liver function tests (LFTs) were trending down. The patient was started on a clear diet with a plan to progress to a fat-free/low-fat diet as tolerated. The treatment concern that persisted at that time was that of the pancreatic cysts in the setting of elevated cancer antigen (CA) 19-9 at 288.4 kU/L.

Four days after admission, the patient was clinically stable, ambulating with no abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting, and was deemed ready for discharge. LFTs (ALT 209 U/L, AST40 U/L, ALP 295 U/L, bilirubin 13 micromole/L) and Hb (81 g/L) had considerably improved. The patient was in sinus rhythm with a plan for further follow-up with Cardiology in the outpatient clinic for evaluation and management of atrial fibrillation. In addition to his diabetes medications (insulin glargine and sitagliptin-metformin), the patient was discharged on prednisolone 5 mg by mouth once daily, bisoprolol 2.5 mg daily, pantoprazole 40 mg daily, montelukast 10 mg once daily, fluticasone-salmeterol 250-50 mcg inhaler twice daily, and ipratropium 20 mcg HFA inhaler 3 times daily. He was scheduled with Gastroenterology for follow up on the hemorrhagic cholecystitis and suspected pancreatic cancer, along with a plan to perform an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS).

Discussion

Apixaban is a direct factor Xa inhibitor that is rapidly absorbed with a half-life of 12 hours. It is predominantly metabolized and inactivated hepatically via CYP3A4/5 and other enzymes. It is essential to have a functional liver to inactivate apixaban. During treatment, apixaban has been associated with a minimal incidence of serum aminotransferase level increases and infrequent occurrences of detectable liver injury [5]. Apixaban has the lowest renal excretion rate through urine (27%) and a lower bleeding rate compared to other direct-acting anticoagulants [6].

Hemorrhagic cholecystitis is a rare complication of apixaban and the time to onset of hemorrhagic cholecystitis from the day of anticoagulant initiation varies widely [7–9]. The pathophysiology includes transmural inflammation and ischemia, which can cause mucosal erosion and bleeding into the gall-bladder lumen [9]. Apixaban can worsen the mucosal damage and hemorrhage in this setting. Symptoms may overlap with other differential diagnoses due to similar presentations such as right upper-quadrant pain, nausea, and vomiting.

In our patient case, hemorrhagic cholecystitis occurred within 1 month after apixaban initiation. Other case reports showed a wide range of such occurrence, ranging from 24 hours [1], 27 days following initiation after cardiac surgery [8], and up to 6 weeks [7]. In the prior case reports, clinical presentations also varied, with some patients presenting with fever and pain radiating to the back, which was not observed in our patient. In addition, prior cases of hemorrhagic cholecystitis with apixaban did not overlap with potential malignancy, unlike the case of our patient with pancreatic tail cysts and elevated tumor markers. While there are limited studies and no strong evidence of the association between pancreatic cancer and hemorrhagic cholecystitis, and the fact that elevated CA19-9 is not necessarily indicative of cancer, the suspected malignancy in our case adds to the overall unique presentation of the hemorrhagic cholecystitis [10–15].

Our patient has a past medical history of T2DM, and CKD stage 2 with previous follow up in our nephrology clinic advising against the use of IV contrast, and this is the reason it was not pursued, as the risks of kidney damage may have exceeded the benefits, and similar outcomes have been reported with or without the use of IV contrast [16]. This same medical history which also included atherosclerosis and hypertension likely did not directly cause the bleeding in the gallbladder, but it may have been a contributing factor through atherosclerotic lesions, although these were not observed in our imaging. There was no evidence of cholangitis in our patient given the lack of a dilated common bile duct or inflammation on presentation. The Tokyo guidelines (TG18) do not specify a definitive criterion for diagnosis, but if cholangitis existed in our case, the severity would have been Grade I (mild) according to the TG18 guidelines [17].

Hasegawa et al previously reported a patient presenting with obstruction and clots in the gallbladder, unlike our patient who did not have these manifestations [3]. The main treatment for hemorrhagic cholecystitis is cholecystectomy to avoid further life-threatening and fatal complications [8,9]. In our patient, surgery was not pursued as a treatment option given the lack of gallstones and need for cholecystectomy, as well as the severity of presentation, which did not necessitate surgical intervention. It is important to note that all the experience with hemorrhagic cholecystitis is based on case reports, with some cases even being diagnosed at the pathology desk. Therefore, surgery in these patients is not a standard of care. Given the circumstance surrounding our patient’s case presentation, absence of gallstones or a septic picture, cholecystectomy or a cholecystectomy tube was not pursued but would have been a first-line consideration had the presentation or severity been different.

Our patient was diagnosed with COVID-19 3 weeks prior to his current admission with an unknown treatment regimen for COVID-19. There are few studies addressing the association between AF and CV events in COVID-19 [18], incidence of AF in COVID-19 [19,20], and mortality rate with pre-existing AF in COVID-19 [21]. We cannot definitely correlate AF with his COVID-19 infection, but we cannot rule it out given the vast incidences of not previously known post-COVID-19 complications [22–25]. Our patient was still on a steroid taper post-COVID-19 pneumonia upon presentation to our institution. A study by Tavernaraki et al showed that chronic use of steroids can be a predisposing factor for gallbladder perforation [26]. In addition, the use of steroids can contribute to a delay in tissue repair, which can also contribute to development of hemorrhagic cholecystitis [27]. Moreover, there have been few cases of hemorrhagic cholecystitis in patients who had COVID-19 infection, even though it is very uncommon, and data are scarce.

Conclusions

Hemorrhagic cholecystitis is rarely reported with the use of the DOAC. Hypertension, T2DM, CKD, in the presence of a recent COVID-19 hospitalization, steroid use, and possible pancreatic cancer may all have contributed to such incidence in the setting of apixaban utilization. Investigating hemorrhagic cholecystitis in the setting of DOAC use in patients with multiple risk factors such as those that existed in our patient is imperative for the proper diagnosis and management.

Figures

References:

1.. Sakharuk I, Martinez P, Laub M, Anticoagulant-induced hemorrhagic cholecystitis with hemobilia after deceased donor kidney transplant and literature review: Int J Surg Case Rep, 2021; 84; 106027

2.. Rahesh J, Anand R, Ciubuc J, Atraumatic spontaneous hemorrhagic cholecystitis.: Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent)., 2020; 34(1); 107-8 [Erratum in: Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2021;34(6): i]

3.. Hasegawa T, Sakuma T, Kinoshita H, A case of hemorrhagic cholecystitis and hemobilia under anticoagulation therapy.: Am J Case Rep, 2021; 22; e927849

4.. Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Bradley JS, Diagnosis and management of complicated intra-abdominal infection in adults and children: Guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.: Clin Infect Dis., 2010; 50(2); 133-64 [Erratum in: Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(12):1695]

5.. : LiverTox: Clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury [Internet], 2012, Bethesda (MD), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Apixaban. [Updated 2023 Feb 16]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548281/

6.. Guo WQ, Chen XH, Tian XY, Li L, Differences in gastrointestinal safety profiles among novel oral anticoagulants: Evidence from a network meta-analysis.: Clin Epidemiol, 2019; 11; 911-21

7.. Azam MU, Ibrahim MA, Perry I, It’s the bloody gallbladder! Apontaneous gallbladder hemorrhage following factor Xa inhibition: J Natl Med Assoc, 2021; 113(3); 252-54

8.. Myers PO, Nguyen-Tang T, Alibegovic-Zaza J, Inan I, Spontaneous haemorrhage on apixaban masquerading as obstructive cholangitis after heart surgery: Eur Heart J, 2019; 40(36); 3066

9.. Kinnear N, Hennessey DB, Thomas R, Haemorrhagic cholecystitis in a newly anticoagulated patient.: BMJ Case Rep., 2017; 2017 bcr2016214617

10.. Gomes AF, Fernandes S, Martins J, Coutinho J, Carcinoma of the gallbladder presenting as haemorrhagic cholecystitis.: BMJ Case Rep, 2020; 13(3); e232953

11.. Kubota H, Kageoka M, Iwasaki H, A patient with undifferentiated carcinoma of gallbladder presenting with hemobilia: J Gastroenterol, 2000; 35(1); 63-68

12.. Takenaka M, Okabe Y, Kudo M, Hemorrhage from metastasis of a 5-mm renal cell carcinoma lesion to the gallbladder detected by contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography: Dig Liver Dis, 2019; 51(5); 743

13.. Sadamori H, Fujiwara H, Tanaka T, Carcinosarcoma of the gallbladder manifesting as cholangitis due to hemobilia: J Gastrointest Surg, 2012; 16(6); 1278-81

14.. Shah R, Klumpp LC, Craig J, Hemorrhagic cholecystitis in a patient with cirrhosis and rectal cancer: Cureus, 2020; 12(4); e7882

15.. Haring MPD, de Cort BA, Nieuwenhuijs VB, [Elevated CA19-9 levels; Not always cancer.]: Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd, 2021; 164; D4048 [in Dutch]

16.. Kang SK, Heacock L, Doshi AM, Comparative performance of non-contrast MRI with HASTE vs. contrast-enhanced MRI/3D-MRCP for possible choledocholithiasis in hospitalized patients.: Abdom Radiol (NY), 2017; 42(6); 1650-58

17.. Yokoe M, Hata J, Takada T, Tokyo Guidelines 2018: Diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos): J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci, 2018; 25(1); 41-54

18.. Cutler MJ, May HT, Bair TL, Atrial fibrillation is a risk factor for major adverse cardiovascular events in COVID-19: Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc, 2022; 43; 101127

19.. Gawałko M, Kapłon-Cieślicka A, Hohl M, COVID-19 associated atrial fibrillation: Incidence, putative mechanisms and potential clinical implications: Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc, 2020; 30; 100631

20.. Slipczuk L, Castagna F, Schonberger A, Incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation in COVID-19 is associated with increased epicardial adipose tissue: J Interv Card Electrophysiol, 2022; 64(2); 383-91

21.. Zuin M, Rigatelli G, Bilato C, Pre-existing atrial fibrillation is associated with increased mortality in COVID-19 patients: J Interv Card Electrophysiol, 2021; 62(2); 231-38

22.. Kramer PJ, Sediqe SA, Giddings OK, A rare case of hemorrhagic cholecystitis in a patient with severe coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19): Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2021; 203(9); A2452

23.. Cirillo B, Brachini G, Crocetti D, Acalcolous hemorrhagic cholecystitis and SARS-CoV-2 infection: Br J Surg, 2020; 107(11); e524

24.. Futagami H, Sato H, Yoshida R, Acute acalculous cholecystitis caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection: A case report and literature review: Int J Surg Case Rep, 2022; 90; 106731

25.. Ying M, Lu B, Pan J, COVID-19 with acute cholecystitis: A case report.: BMC Infect Dis, 2020; 20(1); 437

26.. Tavernaraki K, Sykara A, Tavernaraki E, Massive intraperitoneal bleeding due to hemorrhagic cholecystitis and gallbladder rupture: CT findings: Abdom Imaging, 2011; 36(5); 565-68

27.. Vijendren A, Cattle K, Obichere M, Spontaneous haemorrhagic perfo-ration of gallbladder in acute cholecystitis as a complication of anti-platelet, immunosuppressant and corticosteroid therapy.: BMJ Case Rep., 2012; 2012 bcr1220115427

Figures

In Press

27 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943725

28 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942881

28 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943590

29 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943843

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250