03 July 2023: Articles

An 81-Year-Old Man Presenting with Asthenia and Anorexia After an Alcohol-Induced Hypoglycemic Coma and a Diagnosis of Central Adrenal Insufficiency: A Case Report

Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Nobumasa Ohara1ABCDEF*, Naoko Hirota2B, Toshinori TakadaDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.939840

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e939840

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Alcohol abuse inhibits the ability of the liver to release glucose into the bloodstream, primarily by inhibiting gluconeogenesis, so chronic alcohol abusers exhibit hypoglycemia after drinking alcohol without eating; this is called alcohol-induced hypoglycemia. Central adrenal insufficiency (AI) is characterized by cortisol deficiency due to a lack of adrenocorticotropic hormone. It is challenging to diagnose central AI, as it usually presents with nonspecific symptoms, such as asthenia, anorexia, and a tendency toward hypoglycemia. Here, we report a rare case of central AI that presented with AI symptoms shortly after an alcohol-induced hypoglycemic coma.

CASE REPORT: An 81-year-old Japanese man who had been a moderate drinker for >40 years developed a hypoglycemic coma after consuming a large amount of sake (alcohol, 80 g) without eating. After the hypoglycemia was treated with a glucose infusion, he rapidly recovered consciousness. After stopping alcohol consumption and following a balanced diet, he had normal plasma glucose levels. However, 1 week later, he developed asthenia and anorexia. The endocrinological investigation results indicated central AI. He was started on oral hydrocortisone (15 mg/day), which relieved his AI symptoms.

CONCLUSIONS: Cases of central AI associated with alcohol-induced hypoglycemic attacks have been reported. Our patient developed AI symptoms following an alcohol-induced hypoglycemic attack. His alcohol-induced hypoglycemic attack likely occurred in combination with a developing cortisol deficiency. This case highlights the importance of considering central AI in chronic alcohol abusers presenting with nonspecific symptoms, including asthenia and anorexia, especially when patients have previously experienced alcohol-induced hypoglycemic attacks.

Keywords: adrenal insufficiency, Alcohol Drinking, Hydrocortisone, Hypoglycemia, Hyponatremia, Male, Humans, Aged, 80 and over, Anorexia, Asthenia, Coma, Glucose, Ethanol, Hypoglycemic Agents

Background

Alcohol abuse is a major risk factor for disease and disability [1]. Alcohol abuse inhibits the ability of the liver to release glucose into the bloodstream, primarily by inhibiting gluconeogenesis, so chronic alcohol abusers with or without liver disease exhibit hypoglycemia (typically within 6–36 h) after drinking a moderate-to-large amount of alcohol without eating food; this is called alcohol-induced (fasting) hypoglycemia [2,3].

Central adrenal insufficiency (AI) is an endocrine disorder characterized by cortisol deficiency that is caused by a lack of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) due to an impaired hypothalamic-pituitary axis [4]. It is challenging to diagnose central AI, as it usually presents with nonspecific symptoms, such as asthenia, anorexia, body weight loss, and a tendency toward hypoglycemia [5,6]. Blood tests may also reveal mild anemia, lymphocytosis, eosinophilia, and hyponatremia.

Several cases of central AI associated with alcohol-induced hypoglycemic attacks have been reported [7–9]. There was a case report of a Japanese patient with a long history of undiagnosed central AI who developed an alcohol-induced hypoglycemic coma, which led to the diagnosis of AI [10]. Here, we report a rare case of a chronic alcohol abuser who presented with AI symptoms shortly after an alcohol-induced hypoglycemic coma and was diagnosed with central AI. The aim of this report is to describe the rare clinical course and discuss clues to early diagnosis of central AI in chronic alcohol abusers.

Case Report

An 81-year-old Japanese man was sent to a regional hospital due to coma after drinking a large amount of alcohol without eating. His medical and family histories were unremarkable. He had never experienced brain surgery, radiation exposure, or head trauma, and had never received corticosteroid therapy. He had been drinking moderate amounts of alcohol (approximately 50 g/day) for more than 40 years and drank large amounts of alcohol (80–120 g/day) several times a year. He had weighed approximately 41~43 kg since the age of 40 years. He had never experienced a hypoglycemic episode or coma until 81 years of age, when he consumed a large amount of sake (alcohol, 80 g) in a single afternoon without adequate food intake and went to sleep without eating dinner. The next morning, his family found him unconscious, and he was immediately taken to the hospital by ambulance.

On arrival, the patient was in a coma without seizures: his body temperature was 36.7°C, blood pressure 183/88 mmHg, and pulse rate 87 beats/min. His skin was slightly moist. His mouth was not dry. No heart murmur, chest rales, abdominal tenderness, or peripheral edema were observed. A blood test showed a low plasma glucose (PG) level (34 mg/dL) and low serum levels of sodium (127 mEq/L), potassium (3.3 mEq/L), and chloride (90 mEq/L). He was immediately treated with an intravenous glucose infusion for hypoglycemia. After his PG level increased to above 100 mg/dL, he woke rapidly. The patient was admitted to the hospital the same day.

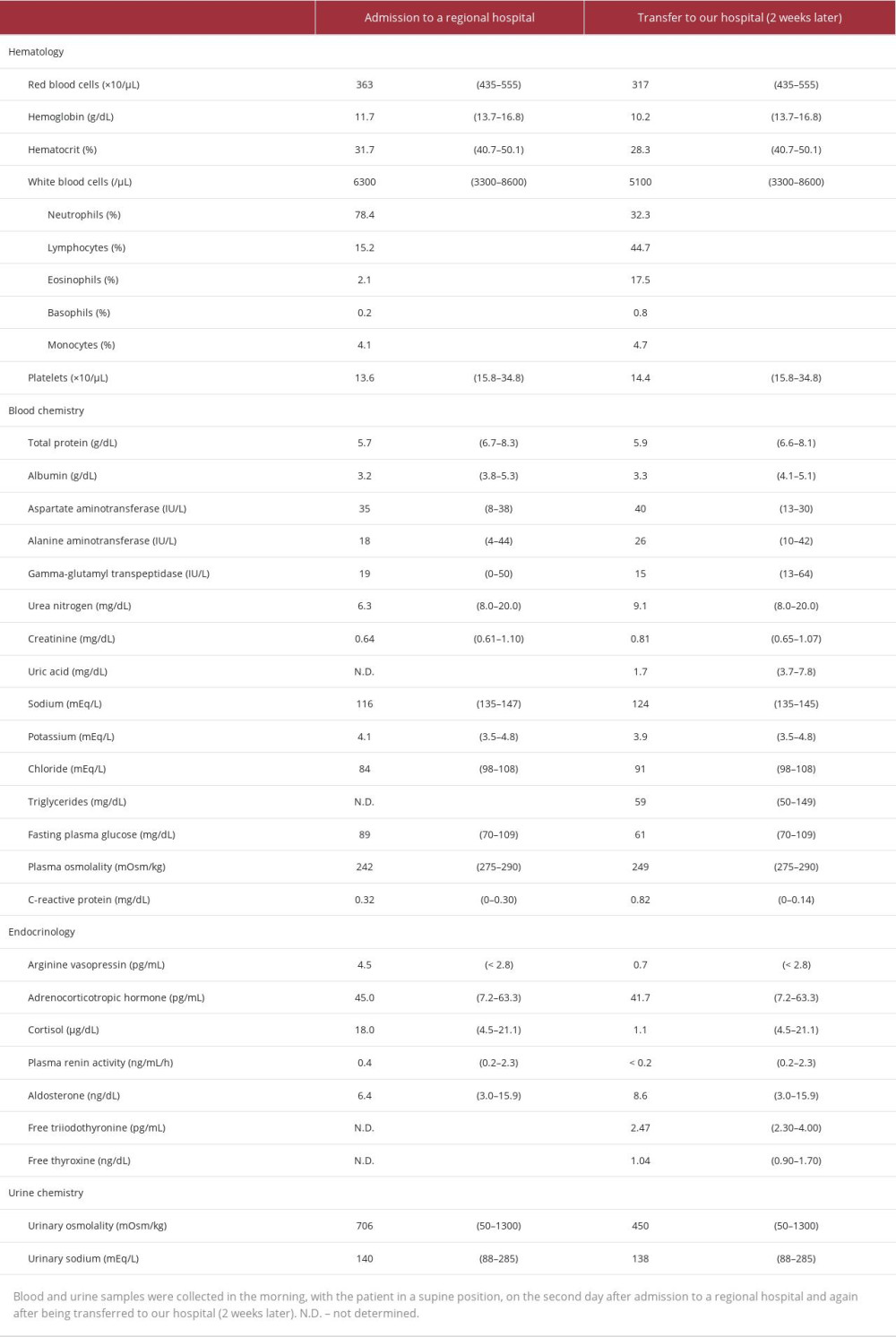

The patient did not have appetite loss and consumed adequate food; his PG levels were 90~130 mg/dL after discontinuing the glucose infusion. His hyponatremia was initially treated with a normal saline infusion. The next morning, he had a normal fasting PG (89 mg/dL) (Table 1), while his hyponatremia worsened (serum sodium level, 116 mEq/L). The plasma arginine vasopressin (AVP) level was high (4.5 pg/mL) [11], while the plasma cortisol level was within the reference range (18.0 μg/dL).

To correct the hyponatremia, 3% hypertonic saline was administered, and the patient’s serum sodium level gradually increased to 130 mEq/L (Figure1). However, 1 week after admission, he developed asthenia and anorexia. His fasting PG levels decreased to 60~70 mg/dL. He was initially suspected to have pneumonia, a urinary tract infection, or gastric ulcer. However, a urinalysis detected no sign of infection or inflammation. Chest and abdominal computed tomography revealed no abnormalities of the lungs, liver, spleen, pancreas, kidneys, or adrenal glands. Gastroscopy revealed no abnormalities of the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum. The patient was transferred to our hospital 15 days after the initial admission for further investigation and management.

Upon arrival at our hospital, the patient’s height, body weight, temperature, blood pressure, and pulse rate were 160 cm, 39.3 kg (body mass index, 15.4 kg/m2), 36.5°C, 99/58 mmHg, and 59 beats/min, respectively. He was conscious but lethargic. He had no symptoms or signs of alcohol withdrawal, such as anxiety, headache, sweating, and tremors, or of Wernicke’s encephalopathy, such as ophthalmoparesis, ataxia, and confusion. A morning blood test revealed mild anemia, lymphocytosis, eosinophilia, and a low cortisol (1.1 μg/dL) level (Table 1).

We suspected AI and performed a detailed endocrinological investigation. A rapid ACTH stimulation test revealed low cortisol release (Table 2A), whereas a prolonged ACTH stimulation test revealed normal cortisol release (Table 2B).

Provocative pituitary function testing (Table 2C) indicated low ACTH and cortisol release after the administration of corticotropin-releasing hormone. The secretory reserves of growth hormone, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and prolactin were normal. The release of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone were mildly decreased, but this finding was not considered clinically significant for his age. Based on these results, central AI was diagnosed.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 2) detected no abnormality in the pituitary or hypothalamus. Therefore, his central AI was considered to be idiopathic.

To treat the central AI, the patient was started on corticosteroid replacement therapy (oral hydrocortisone 15 mg/day) immediately after the endocrinological investigation. His asthenia and anorexia resolved within 1 week (Figure 1). His anemia, lymphocytosis, eosinophilia, mild hypoglycemia, and hyponatremia also improved. The patient was instructed to refrain from alcohol abuse and was discharged.

The patient had persisting central AI and continued oral hydrocortisone (15 mg/day). His subsequent clinical course during follow-up for more than 4 years has been uneventful, without hypoglycemia or hyponatremia.

Discussion

The patient, who had been a moderate drinker for >40 years, experienced an alcohol-induced hypoglycemic coma accompanied by hyponatremia. After treating the hypoglycemia with a glucose infusion, he rapidly recovered consciousness. After stopping alcohol consumption and following a balanced diet, he had normal PG levels. However, 1 week later, he developed asthenia and anorexia and was diagnosed with central AI.

Reported cases of central AI associated with alcohol-induced hypoglycemic attacks followed a variety of clinical courses [7–10]. A 54-year-old male heavy drinker experienced 3 alcohol-induced hypoglycemic comas over 14 months; 1 year later, he lost weight and had repeated hypoglycemic attacks on an empty stomach without drinking alcohol and was then diagnosed with central AI [7]. A 45-year-old man with a 2-month history of anorexia, weight loss, and weakness was diagnosed with central AI and started on oral cortisone acetate (37.5 mg/day) with improved symptoms; however, 2 years later, he began drinking alcohol heavily and stopped taking cortisone and then fell into an alcohol-induced hypoglycemic coma [8]. A 43-year-old male intermittent heavy drinker had repeated alcohol-induced hypoglycemic attacks, including 6 hospitalizations for coma, over 2 years and was started on oral prednisone (5 mg/day) or cortisol (15~30 mg/day) for a therapeutic diagnosis of AI; although he continued to drink alcohol, the number of hypoglycemic attacks decreased significantly; subsequently central AI was diagnosed based on endocrinological examinations [9]. A 48-year-old male heavy drinker who had a 10-year history of AI symptoms, including appetite loss and weight loss, developed an alcohol-induced hypoglycemic coma and was then diagnosed with central AI [10]. In our patient, AI symptoms first appeared soon after an alcohol-induced hypoglycemic attack. This case highlights the importance of considering central AI in chronic alcohol abusers presenting with nonspecific symptoms, including asthenia and anorexia, especially in patients who have previously experienced alcohol-induced hypoglycemic attacks.

It is unclear why our patient developed symptoms of AI after an alcohol-induced hypoglycemic attack. We diagnosed the patient with central AI based on his positive result on the standard-dose rapid ACTH test. The adrenal cortex of patients with central AI can still respond to exogenous ACTH if the test is performed during the first 4–6 weeks after a hypothalamic or pituitary insult [12]. However, in the present case, the test was performed 2 weeks after the appearance of AI symptoms, and the response was extremely low (Table 2A). In addition, the morning cortisol level, which was measured within a day after the hypoglycemic coma, might have exceeded the top of the reference range if the patient’s hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis activity had been intact. These findings suggest that our patient had already suffered from impaired hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis activity with a developing cortisol deficiency when the alcohol-induced hypoglycemic coma occurred. Because deficient cortisol activity inhibits gluconeogenesis [13,14], his alcohol-induced hypoglycemic coma likely occurred in combination with a developing cortisol deficiency, followed by asthenia and anorexia.

The patient had hyponatremia with a high plasma AVP level when he entered an alcohol-induced hypoglycemic coma. Syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone is a common cause of hyponatremia characterized by impaired water excretion and dilutional hyponatremia, but the diagnosis can be made only after excluding other conditions leading to excessive AVP secretion, such as cortisol deficiency [11,15]. Although acute alcohol ingestion induces diuretic effects by inhibiting AVP release, chronic alcohol abuse can cause hyponatremia due to unsuppressed AVP secretion [16]. Additionally, mineralocorticoid-responsive hyponatremia of the elderly (MRHE) is a mildly hypovolemic type of hyponatremia caused by renal sodium loss [17]. In the present case, dehydration or MRHE was deemed unlikely after the patient’s hyponatremia deteriorated after normal saline infusion. His hyponatremia resolved after stopping alcohol consumption and commencing hydrocortisone therapy for central AI. Our patient had likely been suffering from hyponatremia with unsuppressed AVP secretion induced by both chronic alcohol abuse and a developing cortisol deficiency.

Conclusions

We treated a chronic alcohol abuser who presented with asthenia and anorexia 1 week after an alcohol-induced hypoglycemic coma and was diagnosed with central AI. Prompt detection and treatment of hypoglycemia with a glucose infusion, discontinuation of alcohol abuse, and corticosteroid replacement therapy saved his life. This case highlights the need to consider central AI in chronic alcohol abusers presenting with nonspecific symptoms, such as asthenia and anorexia, especially when patients have previously experienced alcohol-induced hypoglycemic attacks.

Figures

References:

1.. Hendriks HFJ, Alcohol and human health: What is the evidence?: Annu Rev Food Sci Technol., 2020; 11; 1-21

2.. Marks V, Wright JW, Endocrinological and metabolic effects of alcohol: Proc R Soc Med, 1977; 70; 337-44

3.. Tetzschner R, Nørgaard K, Ranjan A, Effects of alcohol on plasma glucose and prevention of alcohol-induced hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes – a systematic review with GRADE.: Diabetes Metab Res Rev., 2018; 34 dmrr.2965

4.. Husebye ES, Pearce SH, Krone NP, Kämpe O, Adrenal insufficiency: Lancet, 2021; 397; 613-29

5.. Andrioli M, Pecori Giraldi F, Cavagnini F, Isolated corticotrophin deficiency: Pituitary, 2006; 9; 289-95

6.. Ceccato F, Scaroni C, Central adrenal insufficiency: Open issues regarding diagnosis and glucocorticoid treatment.: Clin Chem Lab Med, 2019; 57; 1125-35

7.. Woeber KA, Arky R, Hypoglycaemia as the result of isolated corticotrophin-deficiency.: Br Med J, 1965; 2; 857-58

8.. Abramson EA, Arky RA, Coexistent diabetes mellitus and isolated ACTH deficiency: Report of a case.: Metabolism, 1968; 17; 492-95

9.. Steer P, Marnell R, Werk EE, Clinical alcohol hypoglycemia and isolated adrenocorticotrophic hormone deficiency.: Ann Intern Med, 1969; 71; 343-48

10.. Baba S, Takase S, Uenoyama R, Isolated corticotrophin-deficiency found through alcohol-induced hypoglycemic coma: Horm Metab Res, 1976; 8; 274-78

11.. Spasovski G, Vanholder R, Allolio B, Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatraemia.: Eur J Endocrinol, 2014; 170; G1-47

12.. Charmandari E, Nicolaides NC, Chrousos GP, Adrenal insufficiency: Lancet, 2014; 383; 2152-67

13.. Exton JH, Regulation of gluconeogenesis by glucocorticoids: Monogr Endocrinol, 1979; 12; 535-46

14.. Kuo T, McQueen A, Chen TC, Wang JC, Regulation of glucose homeostasis by glucocorticoids: Adv Exp Med Biol, 2015; 872; 99-126

15.. Garrahy A, Thompson CJ, Hyponatremia and glucocorticoid deficiency: Front Horm Res, 2019; 52; 80-92

16.. Palmer BF, Clegg DJ, Electrolyte disturbances in patients with chronic alcohol-use disorder: N Engl J Med, 2017; 377; 1368-77

17.. Katayama K, Tokuda Y, Mineralocorticoid responsive hyponatremia of the elderly: A systematic review.: Medicine (Baltimore)., 2017; 96

Figures

In Press

27 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942126

27 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943098

27 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943725

28 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942881

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250