28 December 2023: Articles

Early Diagnosis of Late-Onset Below-Level Neuropathic Pain in an 83 Year-Old Incomplete Tetraplegic Patient: A Charcot Spinal Neuro-Arthropathy Case Report

Unusual clinical course, Challenging differential diagnosis, Congenital defects / diseases

Giulio BerteroDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.940830

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e940830

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Charcot spine (CS), also called neuropathic arthropathy, appears to be triggered by damage to the nervous system (either central or peripheral) impairing proprioception and pain/temperature sensation in the vertebral column. Therefore, the defense mechanisms of altered joints lead to a progressive degeneration of the vertebral joint and surrounding ligaments, which can provoke major spinal instability. Beyond the sensory aspects, mechanic factors are identified as risk factors. While its etiology and pathophysiology remain contested, CS represents a rare and difficult pathology to diagnose at an early stage, owing to its nonspecific clinical symptoms. The diagnosis of CS is probably still underestimated and often occurs only quite late in the disease course.

CASE REPORT: An 83-year-old male patient who had a history of a post-traumatic tetraplegia was diagnosed with CS after 3 years, after describing a recent progressive worsening of neuropathic pain. The diagnosis was earlier than the majority of cases described in the literature. Indeed, in a recent review, the mean time lag between the onset of neurological impairment and the diagnosis of CS was 17.3±10.8 years.

CONCLUSIONS: This case report demonstrates the benefits of early diagnosis of CS when confronted by the clinical and radiological criteria. Therefore, it seems important to be able to evoke this neuropathic spinal arthropathy sufficiently in time to prevent its disabling consequences in patients with spinal cord injury, in terms of quality of life and independence.

Keywords: Arthropathy, Neurogenic, Spinal Cord Injuries, chronic pain, Low Back Pain, Quadriplegia, case reports

Background

Charcot spine (CS), also called neuropathic arthropathy, was initially described by Charcot in patients with tertiary syphilis [1]. The first patient with spinal neuroarthropathy was then reported in 1884 [2]. By definition, CS appears to be a result of any damage to the nervous system (either central or peripheral) causing impaired proprioception and pain/temperature sensation in the vertebral column. Therefore, the defense mechanisms of altered joints ultimately lead to a progressive degeneration of the vertebral joint and surrounding ligaments, which in turn can provoke major spinal instability. Reports in the literature also suggest a contribution of the sitting imbalance consequent to the spinal cord injury (SCI) as one of the risk factors for CS [3–5].

Beyond the sensory aspects, mechanic factors are also identified as risk factors. In patients with SCI, particularly if they are active paraplegic patients, the hinge junctions (thoracolumbar and lumbosacral spine) are areas susceptible to developing CS lesions. For those areas in particular, repetitive and excessive loads are exerted even more when spinal fusion or laminectomy have been performed [6]. Moreover, in patients with SCI, other potential impacts include reduced lumbar lordosis, and therefore kyphosis can develop, as well as scoliosis, which can exacerbate the degenerative process [7]. While its etiology and pathophysiology continue to be debated, CS represents a rare and difficult pathology to diagnose at an early stage, such as in the present case, owing to its nonspecific clinical symptoms.

The purpose of this article is to highlight the possibility of diagnosing CS earlier than it is commonly done. In writing this case report, we reviewed the literature about diagnostic criteria, clinical and radiological, and differential diagnoses of CS. Improving knowledge of this pathology will make it possible to care for patients at an early stage. Early diagnoses will be useful in preventing the sometimes devastating consequences that come with the progression of CS.

Case Report

An 83-year-old male patient who had an history of a post-traumatic tetraplegia with a neurologic level C3 American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale D [8] for 3 years was admitted to our unit. He presented with neuropathic pain that developed insidiously in the previous year in both legs, without any other deficit. The patient described a recent progressive worsening of pain. However, no history of trauma had been reported during the past year. The pain had a negative impact on the patient’s daily quality of life. The patient had normal vital signs, and the laboratory test results were unre-markable, except for an already known chronic renal failure (mild), which was stable.

In comparison with the previous year’s American Spinal Injury Association examination, an improvement of the assessment of the key muscles of the lower limbs was noticed (Lower Extremity Motor Score: right side 24/25; left side 22/25). The examination of the sensitivity in key sensory points revealed impaired sensitivities in L4, L5, and S1 of the right side, which were previously normal. The neuropathic pain was localized on the L4, L5, and S1 dermatomes in both sides. The patellar (L4) and Achilles (S1) reflexes were reduced in both sides but predominantly on the right side. The plantar reflex was indifferent in both sides. The rest of the examination was otherwise strictly similar to the one conducted 2.5 years before, when the patient did not have neuropathic pain in the legs. Functionally, the patient walked without aid but still had an ataxic gait and a decrease of his balance functions.

The lumbar spine anteroposterior projection X-ray, complemented by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine, showed a sinistroconvex scoliosis centered in L4, associated with below-level multi-level significant disc degenerations (Figures 1, 2). Complete findings were as follows: (1) At L3–L4 level: posterior circumferential bulge (predominantly on the right side) resulting in moderate foraminal narrowing and extraforaminal conflict with the right L3 emerging root; degenerative damage to the facet joints; and hypertrophic osteophytosis within paravertebral soft tissue. (2) At the L4–L5 level: Modic I type alteration (edema) of the vertebral endplates due to significant disc degeneration and important intersomatic pinching; presence of a disco-osteophytic crown predominantly on the right

Discussion

The diagnosis of CS is most likely still underestimated and often occurs only quite late in the course of the disease. Our case was diagnosed earlier than the majority of cases described in the literature. Indeed, in a recent review, the mean time lag between the onset of neurological impairment and the diagnosis of CS was 17.3±10.8 years [9]. This is due to the relatively non-specific symptoms. Even if this case appears to still be a moderate stage, many clinical signs and radiological criteria of CS described in the literature can be distinguished.

We listed the diagnostic criteria found in the literature in a tabular format [9] (Table 1).

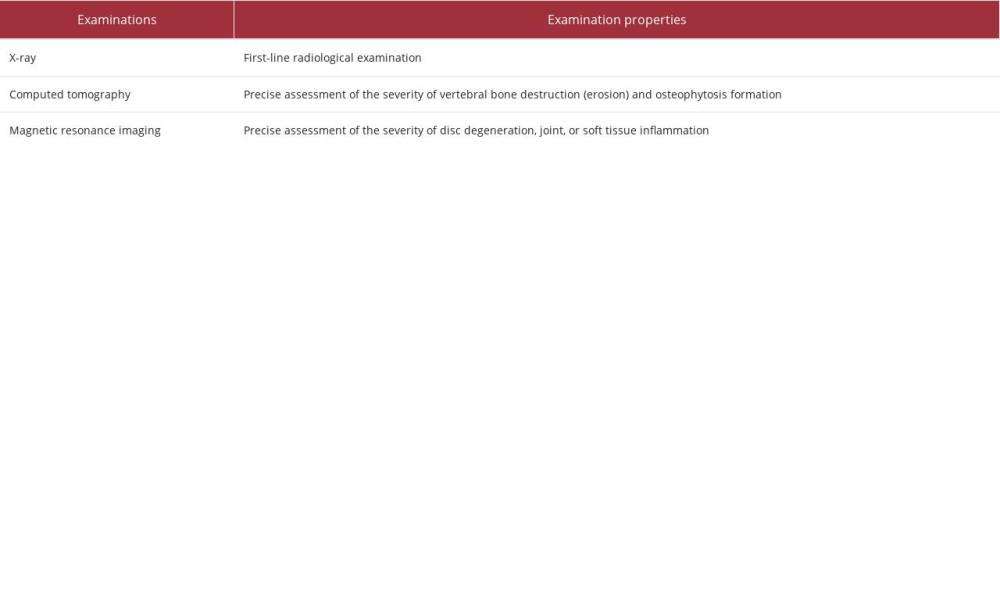

The first para-clinical step is to perform a radiological examination of the spinal column; based on the result, it will be decided whether to proceed to a second level examination (Table 2).

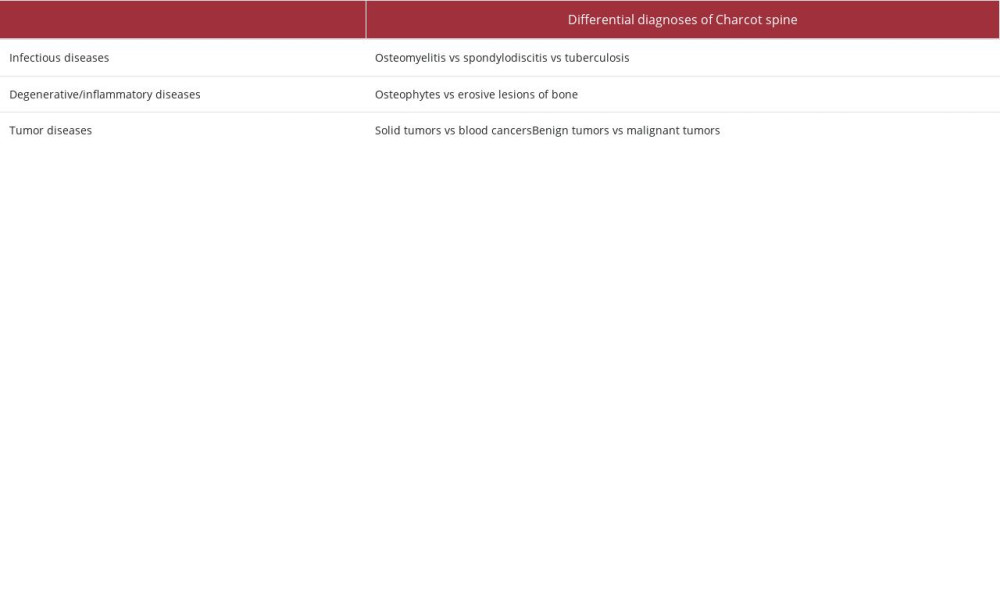

Differential diagnoses of CS are divided into 3 major groups: infectious diseases, degenerative/inflammatory diseases, and tumor diseases. Infectious pathologies can be osteomyelitis, spondylodiscitis, and tuberculosis. The clinical presentation is usually typical of an infection in the case of osteomyelitis and spondylodiscitis, and is more nuanced in the case of tuberculosis. Infectious diseases are detectable with laboratory investigations aimed at finding infectious markers. In these cases, a computed tomography scan finds typical and easily recognizable signs of collection. Degenerative/inflammatory diseases often present an evolution similar to CS, but they are not related to nervous system damage. Also in inflammatory diseases, laboratory tests can find inflammatory markers. Radiologically, osteophytes are frequently found in degenerative diseases, erosive lesions of bone are found in inflammatory diseases. Tumor diseases present great variability in clinical presentation, which must correlate with an anamnestic history suggestive of this pathology. Laboratory examinations can identify alterations in the blood formula and platelets and non-specific signs of inflammation. Certain tumor markers can be sought in cases of possible suspicion. On radiological examinations, masses of various shapes and topographical location (soft tissue, bone, or cavity) can appear, depending on the origin of the disease. A biopsy may be indicated [10,11] (Table 3).

Our patient showed characteristic clinical (spinal pain, walking imbalance, changes in neurological status) and radiological signs (important disc degeneration, vertebral degeneration that mirrors the disc space, destruction of facet joints, and osteophytosis within paravertebral soft tissues) of the CS. He also had an early radiological scoliosis. No other differential diagnosis was considered, and there were no criteria for suspecting an infection.

We have identified 3 main limitations in this case report. The first limitation is the impossibility of generating statistical information, owing to an insufficient sample. The second limitation is the impossibility of identifying a possible cause that interfered with the patient’s clinical course and accelerated the evolution of CS. The third limitation is the difficulty of generalizing what we present in this case report, which is a situation of uncommon disease progression, to the CS population [12].

The fact that more cases of early presentation of CS may be reported in the future will enable the identification of predisposing factors for the rapid development of CS. In addition, this will allow researchers to determine whether there are any differences in prognosis compared with CS cases with a classic course.

Conclusions

This case report points to the interest of diagnosing CS early when confronted by the clinical and radiological criteria. In fact, a recent literature review has emphasized how orthopedic treatment, including physical therapy and possible brace, can have a positive effect on stabilization and pain [13,14]. Early diagnosis can allow patients to benefit from orthopedic and rehabilitation treatment without waiting for the situation to evolve, as the patient will then necessarily be directed toward surgical treatment [14,15]. This also underlines the importance of conducting regular clinical and radiological follow-up of patients with SCI and focusing on their entire cervico-thoracolumbar spine, not only the initial site of injury [16]. Finally, it seems important to be able to evoke this neuropathic spinal arthropathy sufficiently in time to prevent its disabling consequences in patients with SCI, in terms of quality of life and independence [17].

Figures

References:

1.. Charcot JM, Sur quelques arthropathies qui paraissant dependre dune lesion du cerveau ou de la modelle epiniere: Arch Physiol Norm Pathol, 1868; 1; 161

2.. Kroning G, Spondylolisthese bei einem Tabiker: Zeit Klin Med, 1884(Suppl. 7); 165 [in German]

3.. Abou L, de Freitas GR, Palandi J, Ilha J, Clinical instruments for measuring unsupported sitting balance in subjects with spinal cord injury: A systematic review: Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil, 2018; 24(2); 177-93

4.. Serra-Añó P, Pellicer-Chenoll M, Garcia-Massó X, Sitting balance and limits of stability in persons with paraplegia: Spinal Cord, 2013; 51(4); 267-72

5.. De Iure F, Chehrassan M, Cappuccio M, Amendola L, Sitting imbalance cause and consequence of post-traumatic Charcot spine in paraplegic patients: Eur Spine J, 2014; 23(Suppl. 6); 604-9

6.. Vora D, Schlaff CD, Rosner MK, Surgical management of a complex case of Charcot arthropathy of the spine: A case report: Spinal Cord Ser Cases, 2019; 5; 73

7.. Grassner L, Geuther M, Mach O, Charcot spinal arthropathy: An increasing long-term sequel after spinal cord injury with no straightforward management: Spinal Cord Ser Cases, 2015; 1; 15022

8.. Kirshblum S, Snider B, Rupp R, Read MS, Updates of the international standards for neurologic classification of spinal cord injury: 2015 and 2019: Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am, 2020; 31(3); 319-30

9.. Barrey C, Massourides H, Cotton F, Charcot spine: Two new case reports and a systematic review of 109 clinical cases from the literature: Ann Phys Rehabil Med, 2010; 53(3); 200-20

10.. Ledbetter LN, Salzman KL, Sanders RK, Shah LM, Spinal neuroarthropathy: Pathophysiology, clinical and imaging features, and differential diagnosis: Radiographics, 2016; 36(3); 783-99

11.. Farrugia PR, Bednar D, Oitment C, Charcot arthropathy of the spine: J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 2022; 30(21); e1358-e65

12.. Nissen T, Wynn R, The clinical case report: A review of its merits and limitations: BMC Res Notes, 2014; 7; 264

13.. Del Arco Churruca A, Vázquez Bravo JC, Charcot arthropathy in the spine. Experience in our centre. About 13 cases. Review of the literature: Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol (Engl Ed), 2021 [Online ahead of print]

14.. Urits I, Amgalan A, Israel J, A comprehensive review of the treatment and management of Charcot spine: Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis, 2020; 12; 1759720 X20979497

15.. Lee D, Dahdaleh NS, Charcot spinal arthropathy: J Craniovertebr Junction Spine, 2018; 9(1); 9-19

16.. Abramoff BA, Sudekum VL, Wuermser LA, Ahmad FU, Very early Charcot spinal arthropathy associated with forward bending after spinal cord injury: A case report: Spinal Cord Ser Cases, 2019; 5; 19

17.. Staloch MA, Hatem SF, Charcot spine: Emerg Radiol, 2007; 14(4); 265-69

Figures

In Press

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943174

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943136

21 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943645

21 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942921

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250