28 December 2023: Articles

IgA Vasculitis as a Potential Complication of Fourth-Line Chemotherapy with Tegafur/ Gimeracil/Oteracil (S-1) in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Case Report

Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Ryotaro Yoneoka1ABCDEF, Hajime Kasai234ABCDEF*, Aoi Hino2ABCDE, Ayumi Hayashi5BCDE, Atsushi Sasaki2BCDE, Masayuki Ota6BCDE, Katsuhiko Asanuma5DE, Takuji Suzuki2DEDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.941826

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e941826

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis is a systemic vasculitis that involves the small vessels. It is mainly characterized by skin symptoms such as purpura, arthritis/arthralgia, abdominal symptoms, and nephropathy, which are caused by IgA adherence to the vessel walls. Herein, we report the case of an advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and a purpuric skin rash of the legs that developed during fourth-line chemotherapy with tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil (S-1).

CASE REPORT: A 68-year-old man diagnosed with NSCLC 2 years ago was undergoing S-1 as fourth-line chemotherapy when he developed purpura and edema on the lower extremities. Biopsy renal specimens were consistent with IgA vasculitis. Considering his medical history, both IgA vasculitis induced by S-1 and a paraneoplastic syndrome were considered, although the exact cause could not be identified. Subsequently, chemotherapy was discontinued because of his deteriorating general condition, and he received optimal supportive care. The purpura spontaneously disappeared; however, his ascites and renal function deteriorated. Systemic steroids improved renal function, but the ascites did not resolve. One month after being diagnosed with IgA vasculitis, the patient died due to deterioration of his general condition.

CONCLUSIONS: This case emphasizes the occurrence of IgA vasculitis during lung cancer treatment and its potential impact on the disease course of lung cancer. Moreover, the possible causes of IgA vasculitis in this case were paraneoplastic syndrome or S-1 adverse effects, but further case series are needed to gain a more comprehensive understanding. Refractory, steroid-unresponsive ascites may occur as an abdominal manifestation of IgA vasculitis.

Keywords: Tegafur, IgA Vasculitis, lung neoplasms, Paraneoplastic Syndromes, Purpura

Background

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis is a systemic blood vessel inflammation caused by adherence of IgA antibodies to the vessel walls [1]. It is characterized by purpura, arthritis/arthralgia, abdominal symptoms, and nephropathy [1]. IgA vasculitis is most frequently observed in children aged 3–10 years, with a male predominance [1]. IgA vasculitis rarely affects adults, and when it does, it is often associated with malignant tumors, including lung cancer, where it can occur as a paraneoplastic syndrome [1]. IgA vasculitis has been associated with small cell lung cancer and lung squamous cell carcinoma [2–9]. Adult patients with IgA vasculitis are often subsequently diagnosed with malignant tumors [3–11]. Despite this, there have been few case reports of IgA vasculitis-associated lung cancer [2–16]; further, its pathogenesis and clinical features remain unclear.

Tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil (S-1) is commonly used in systemic chemotherapy for various tumors, including lung cancer. Although there have been reports of patients with gastric cancer who developed thrombotic microangiopathy and presented purpura due to S-1 [17], no reports of purpura associated with vasculitis due to S-1 have been documented.

Herein, we present a case of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and a purpuric skin rash of the legs that developed during fourth-line chemotherapy with S-1.

Case Report

A 66-year-old male patient was referred to our hospital due to an abnormal shadow noted on a chest radiograph during a health checkup (Figure 1A). A transbronchial lung biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of left lung upper-lobe NSCLC (clinical T4N2M0, Stage IIIB) (Figure 2), along with pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. After undergoing 3 lines of chemotherapy, the patient received 7 cycles of fourth-line chemotherapy comprising S-1 (Figure 3). Following the S-1 chemotherapy, purpura and edema developed in his lower extremities. The patient’s age at this point was 68 years. Consequently, he was referred to our hospital (Figure 4).

Upon presentation to our hospital, the patient’s weight and height were 71.1 kg and 172.5 cm, respectively. His vital signs were stable, except for a pulse oximetry reading of 92% in ambient air. Physical examination revealed soft, non-tender, and flat abdomen. Palpable purpura and edema in multiple locations were present in his lower extremities. He did not exhibit joint deformity or arthralgia. Chest radiography revealed the presence of lung cancer, which appeared larger than that observed at the start of the fourth-line chemotherapy (Figure 1B, 1C). Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed a mass measuring 54×60 mm in the left upper lobe, which was larger than that observed at the start of the fourth-line chemotherapy. However, abdominal CT revealed no organic bilateral renal abnormalities. His hematologic and blood chemical values were as follows: 9.0 g/dL hemoglobin and 872 mg/dL IgA. Urine analysis revealed proteinuria at 6.34 g/gCre and hematuria with >100 erythrocytes per high-power field. The findings were negative for all autoantibodies (Table 1). After confirmation of the purpura, S-1 was discontinued due to the possibility of drug-induced purpura. A bone marrow biopsy did not reveal significant findings. Fourteen days after the appearance of purpura, the patient visited a dermatologist, at which time the purpura had slightly faded. The dermatologist did not perform a skin biopsy in this case because the skin rash was deemed unsuitable for biopsy. Although the purpura remitted, abdominal bloating appeared and progressively worsened. Subsequently, he was hospitalized and underwent a renal biopsy. Histopathological examination revealed proliferation of the mesangial areas, which is characteristic of IgA vasculitis. Moreover, immuno-fluorescent staining showed IgA (2+) and C3 (3+) (Figure 5). The diagnosis of IgA vasculitis was made based on the presence of palpable purpura and renal pathology, satisfying 2 of the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology/ Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation/ Paediatric Rheumatology European Society (EULAR/PRINTO/ PRES) criteria [18,19]. Considering his deteriorating general condition, chemotherapy was discontinued, and he received optimal supportive care. The abdominal bloating was attributed to ascites caused by IgA vasculitis. Peritoneal puncture was performed; additionally, the ascites was determined to be transudative according to Light’s criteria [20]. After admission, serum creatinine levels continued to rise. Steroids (betamethasone 8 mg/day) were administered to alleviate these symptoms and treat IgA vasculitis. Although renal function improved with steroid therapy, the ascites progressed.

Goreisan, a type of Kampo medicine, was administered in addition to steroids (Figure 3A). However, despite these interventions, the ascites continued to progress, and renal function deteriorated. The patient’s general condition gradually worsened, and he succumbed to his illness 3 months after the onset of purpura.

Discussion

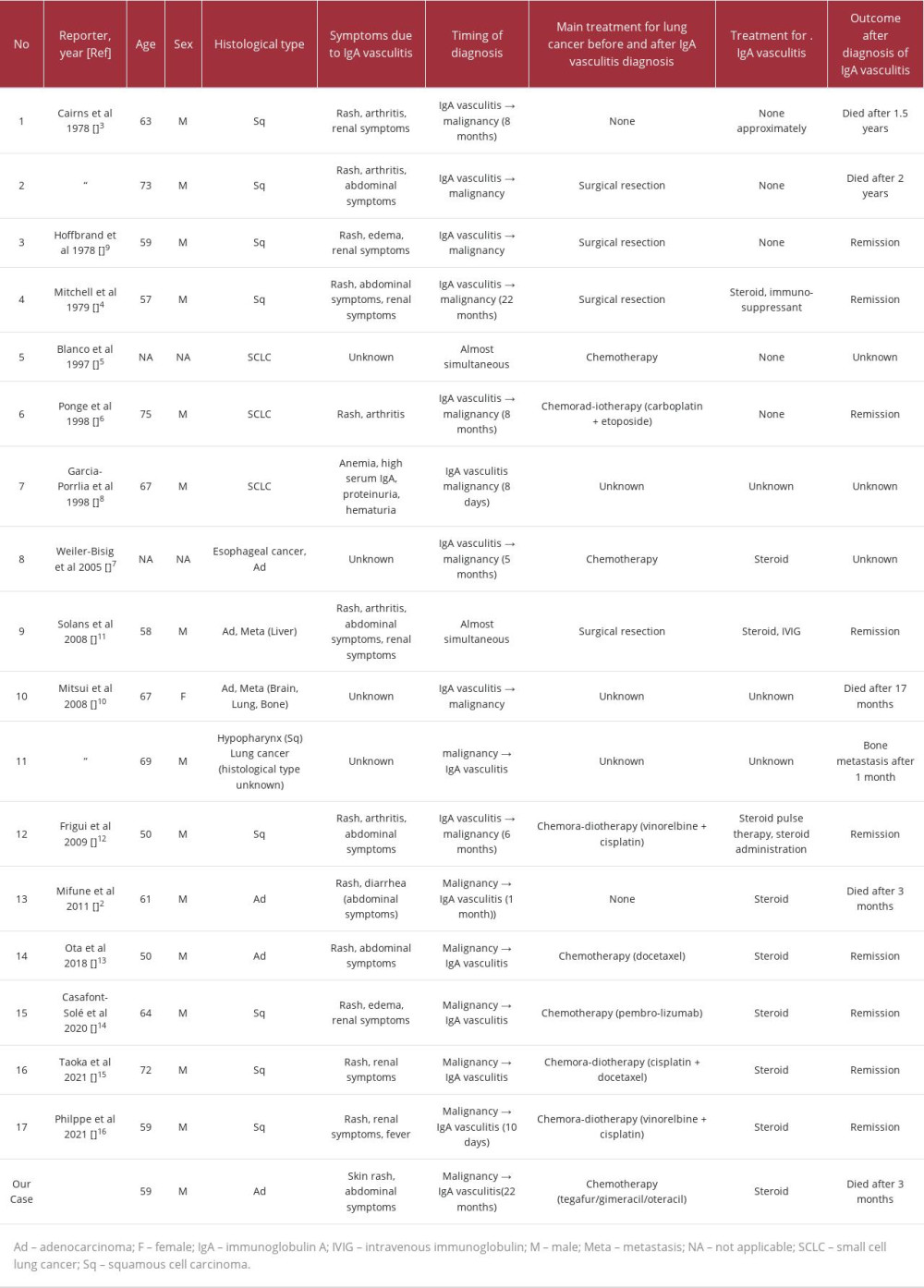

This case report presents the notable clinical finding that IgA vasculitis may develop during chemotherapy as the tumor progresses, suggesting a possible association with paraneoplastic syndromes. Additionally, the abdominal manifestations of IgA vasculitis can include massive ascites, which may be refractory. IgA vasculitis can develop even during long-term chemotherapy following a lung cancer diagnosis. We carefully reviewed previously reported similar cases and extracted the following information: age, sex, histological type, IgA vasculitis symptoms, timing of diagnosis, treatment for lung cancer, treatment for IgA vasculitis, and outcome [2–16]. We identified 14 reports of 17 cases of IgA vasculitis-associated lung cancer (Table 2), with the first report being published in 1978. Including our case, the mean patient age was 62.3 years (range 50–73 years), with 16 male and 2 female patients. The most common lung cancer histological type was squamous cell carcinoma (n=8; 44.4%), followed by adenocarcinoma (n=6; 33.3%) and small cell lung cancer (n=2; 11.1%). Purpura were present in all cases (100%), and the most common complication other than purpura was abdominal symptoms (n=8; 44.4%), followed by renal involvement (n=7; 38.9%). From the 1970s to the 2010s, most cases involved malignant tumors diagnosed as a result of vasculitis. Subsequently, there has been an increasing number of cases of vasculitis caused by tumor progression. The present case is characterized by 2 distinct aspects: (1) IgA vasculitis developed at an advanced stage of diagnosis of lung cancer, and (2) the emergence of refractory ascites was due to poor responsiveness to steroids. While the purpura did not improve after the drug was discontinued, the possibility of chemotherapy-induced IgA vasculitis cannot be completely ruled out. In contrast, the uncontrolled and deteriorating progression of the lung cancer after 6 courses of S-1 chemotherapy also suggested the possibility of IgA vasculitis due to paraneoplastic syndrome. In any case, IgA vasculitis can occur during the long-term treatment of lung cancer. Therefore, IgA vasculitis should be considered as a differential diagnosis in cases of symptoms such as rash and abdominal pain, when they occur during the treatment of lung cancer.

In our case, several differential diagnoses, including immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), hemolytic uremic syndrome, leukemia, and coagulopathy, were considered for the purpura. Certainly, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and mild coagulopathy were present in this case, when the purpura occurred. In our case, since a bone marrow biopsy revealed no significant findings, ITP and leukemia were ruled out. Since skin biopsies were not performed, these diagnoses cannot be completely ruled out. However, the renal involvement was consistent with IgA nephritis, and other clinical findings were suggestive of IgA vasculitis. In addition, other clinical symptoms and laboratory findings were not more suggestive of these differential diagnoses than of IgA vasculitis.

Additionally, IgA nephropathy can be asymptomatic or idiopathic, thus it is possible that this patient originally had IgA nephritis. However, renal function was normal before diagnosis, and no abnormality was seen in the urinalysis. Therefore, the existence of IgA nephropathy prior to the diagnosis of lung cancer could be ruled out.

Although the association of IgA vasculitis with lung cancer has been reported for squamous and small cell carcinoma in the 20th century, there has been an increase in the number of lung adenocarcinoma cases involving IgA vasculitis since the beginning of the 21st century. Ten cases have been reported from the 21st century. This could be attributed to the prolonged prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma resulting from medical advancements allowing for early detection and treatment, leading to an increase in the number of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. It is important to consider IgA vasculitis during the treatment of lung cancer, regardless of its histologic type.

Abdominal manifestations of IgA vasculitis may include massive ascites, which exhibit poor responsiveness to steroids. Moreover, abdominal symptoms of IgA vasculitis generally include abdominal pain, vomiting, hematochezia, and hemorrhagic stool [1]. According to Japanese guidelines, standard treatments for these abdominal symptoms include antihista-mines, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroids, and dried concentrated human factor XIII blood coagulation products [21]. As mentioned above, among the case series we examined, 8 cases (44.4%) presented with abdominal symptoms, with one reporting diarrhea, although the details of the other 7 cases could not be ascertained. In our case, the patient experienced massive ascites refractory to steroids, which led to continuous abdominal pain and loss of appetite, significantly reducing the patient’s quality of life. The ascites was considered to be caused by IgA vasculitis because there was no other fluid accumulation, such as pleural effusions, despite the presence of hypoalbuminemia and renal impairment. After admission, the patient underwent steroid treatment for symptomatic palliation and IgA vasculitis; however, no improvement was observed in ascites accumulation. Taken together, massive as-cites caused by IgA vasculitis can significantly reduce quality of life, even in the terminal stages of lung cancer.

Some manifestations of IgA vasculitis, including ascites, may be refractory to steroids, depending on the condition of the underlying disease. As shown in Table 2, 9 out of 18 (50.0%) patients who received chemotherapy exhibited a good response to steroid treatment for IgA vasculitis [3–11]. This could be attributed to the fact that their lung cancer was well-controlled. In contrast, chemotherapy was discontinued in our case since the lung cancer continued to worsen. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the pathophysiological mechanism underlying IgA vasculitis and to inform development of therapeutic interventions for paraneo-plastic IgA vasculitis, even in patients with poorly controlled cancer.

Conclusions

IgA vasculitis can develop in advanced stages of lung cancer and may be involved in the disease course of lung cancer. The causes of IgA vasculitis in this case could have been paraneoplastic syndrome or adverse effects of S-1 chemotherapy. Further case series are needed to understand the details of IgA vasculitis associated with lung cancer. Clinicians should be aware that the abdominal manifestations of IgA vasculitis may include ascites, which may be unresponsive to steroids and challenging to treat.

Figures

References:

1.. Maritati F, Canzian A, Fenaroli P, Vaglio A, Adult-onset IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein): Update on therapy: Presse Med, 2020; 49; 104035

2.. Mifune D, Watanabe S, Kondo R, Henoch Schönlein purpura associated with pulmonary adenocarcinoma: J Med Case Rep, 2011; 5; 226

3.. Cairns SA, Mallick NP, Lawler W, Williams G, Squamous cell carcinoma of bronchus presenting with Henoch-Schönlein purpura: Br Med J, 1978; 2; 474-75

4.. Mitchell DM, Hoffbrand BI, Relapse of Henoch-Schönlein disease associated with lung carcinoma: J R Soc Med, 1979; 72; 614-15

5.. Blanco R, González-Gay MA, Ibáñez D, Henoch-Schönlein purpura as a clinical presentation of small cell lung cancer: Clin Exp Rheumatol, 1997; 15; 545-47

6.. Ponge T, Boutoille D, Moreau A, Systemic vasculitis in a patient with small-cell neuroendocrine bronchial cancer: Eur Respir J, 1998; 12; 1228-29

7.. Weiler-Bisig D, Ettlin G, Brink T, Henoch-schonlein purpura associated with esophagus carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the lung: Clin Nephrol, 2005; 63; 302-4

8.. García-Porrúa C, González-Gay MA, Cutaneous vasculitis as a paraneoplastic syndrome in adults: Arthritis Rheum, 1998; 41; 1133-35

9.. Hoffbrand BI, Carcinoma of bronchus presenting with Henoch-Schönlein purpura: Br Med J, 1978; 2; 831

10.. Mitsui H, Shibagaki N, Kawamura T, A clinical study of Henoch-Schönlein purpura associated with malignancy: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2009; 23; 394-401

11.. Solans-Laqué R, Bosch-Gil JA, Pérez-Bocanegra C, Paraneoplastic vasculitis in patients with solid tumors: Report of 15 cases: J Rheumatol, 2008; 35; 294-304

12.. Frigui M, Kechaou M, Ben Hmida M, [Adult Schönlein-Henoch purpura associated with epidermoid carcinoma of the lung.]: Nephrol Ther, 2009; 5; 201-4

13.. Ota S, Haruyama T, Ishihara M, Paraneoplastic IgA vasculitis in an adult with lung adenocarcinoma: Intern Med, 2018; 57; 1273-76

14.. Casafont-Solé I, Martínez-Morillo M, Camins-Fàbregas J, IgA vasculitis and polymyalgia rheumatica induced by durvalumab: Transl Lung Cancer Res, 2020; 9; 421-23

15.. Taoka M, Ochi N, Mimura A, IgA vasculitis in a lung cancer patient during chemoradiotherapy: Ther Clin Risk Manag, 2021; 17; 571-75

16.. Philippe É, Barnier A, Menguy J, Henoch-Schönlein purpura associated with lung cancer: When paraneoplastic manifestations impede oncological management: Case Rep Immunol, 2021; 2021; 8847017

17.. Muto J, Kishimoto H, Kaizuka Y, Thrombotic microangiopathy following chemotherapy with S-1 and cisplatin in a patient with gastric cancer: A case report: In Vivo, 2017; 31; 439-41

18.. Ruperto N, Ozen S, Pistorio A, EULAR/PRINTO/PRES criteria for HenochSchönlein purpura, childhood polyarteritis nodosa, childhood Wegener granulomatosis and childhood Takayasu arteritis: Ankara 2008. Part I: Overall methodology and clinical characterisation: Ann Rheum Dis, 2010; 69; 790-97

19.. Reamy BV, Williams PM, Lindsay TJ, Henoch-Schönlein purpura: Am Fam Physician, 2009; 80; 697-704

20.. Light RW, Macgregor MI, Luchsinger PC, Ball WC, Pleural effusions: The diagnostic separation of transudates and exudates: Ann Intern Med, 1972; 77; 507-13

21.. Isobe M, Amano K, Arimura Y, JCS 2017 guideline on management of vasculitis syndrome – Digest Version: Circ J, 2020; 84; 299-359

Figures

In Press

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942853

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942660

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943174

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943136

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250