11 December 2023: Articles

The Silent Threat: Endocarditis Unveiling Heart Failure and Severe Pulmonary Hypertension

Challenging differential diagnosis, Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Daniel BoctorDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942160

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e942160

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Bartonella quintana is a slow-growing gram-negative bacterium that can cause severe culture-negative endocarditis. In many cases, its insidious onset can be difficult to diagnose given the variable symptoms in the early phases of the disease. This delay in detection and thus treatment can cause advanced consequences of the disease, including heart failure and severe pulmonary hypertension.

CASE REPORT: A 51-year-old man presented to the Emergency Department with signs and symptoms indicating an acute stroke. Further investigation showed that the source was cardioembolic, and despite negative blood cultures, endocarditis was suspected due to echocardiogram findings. Bartonella endocarditis was diagnosed based on serology results. Further testing indicated severe pulmonary hypertension, a sequelae of chronic heart failure in the setting of endocarditis. This caused a significant delay in valvular repair surgery. This case illustrates the progression from acute to chronic infection, the sequelae of this disease process, and the considerations involved in management.

CONCLUSIONS: Bartonella is an under-appreciated cause of endocarditis and can evolve into chronic disease with clinical consequences requiring nuanced management. We described a case of chronic culture-negative endocarditis that presented with acute embolic stroke and the sequelae of severe multi-valvular disease in a patient with recent incarceration and unstable housing. This case provides clinicians with valuable insight into the recognition of Bartonella endocarditis, the variable clinical presentations of this pathology, the nuanced and multifactorial approaches to medical management, and the indications for surgery.

Keywords: Bartonella quintana, embolic stroke, Endocarditis, Heart Failure, Hypertension, Pulmonary

Background

Case Report

A 51-year-old man with no significant past medical history presented to the hospital with acute aphasia and confusion. He was recently incarcerated in the central valley of California for 2 years and previously was unstably housed in the San Francisco Bay area.

On arrival, he was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. His cardiovascular examination revealed a II/VI holosystolic murmur at the apex, a II/VI diastolic murmur at the right upper sternal border, distended jugular veins, and pulmonary crackles. He was disoriented and aphasic but had no other localizing neurological findings. Laboratory studies were significant for a hematocrit level of 30.2% (baseline 40% two years prior) and a white blood cell count of 7.0 k/uL (reference range 3.9–11.7 k/uL). No inflammatory markers were collected on admission, given his acute stroke presentation. Computed tomography of the head revealed an intracranial hemorrhage in the left parieto-occipital region with mild local mass effect. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain with gadolinium contrast showed a 5-mm pseudoaneurysm in the M4 parietal branch of the middle cerebral artery (Figure 1). The patient underwent urgent coil embolization of the pseudoaneurysm, and the source of the intracranial hemorrhage was secured. Given its distal location, a mycotic pseudoaneurysm was suspected [5].

Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography showed concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricle, with an ejection fraction of 66%, vegetations on the aortic and mitral valves (Figures 2, 3) associated with moderate-to-severe regurgitation, and elevated estimated right ventricular systolic pressure (100 mmHg). The estimated size of the vegetation on the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve was 0.3×0.4 cm (by transesophageal echocardiography) and on the aortic valve was 1.2×0.5 cm (by transthoracic echocardiography). Although blood cultures remained negative, empiric antibiotic therapy was initiated with intravenous ceftriaxone, doxycycline, and rifampin. Indirect immunofluorescent antibody testing (ARUP laboratories) revealed

In agreement with guidelines from the American Association of Thoracic Surgery (AATS), the patient was considered for urgent surgical replacement of his aortic and mitral valves. Given the medical complexity, a multidisciplinary team, including the cardiology, cardiothoracic surgery, neurology, and infectious disease services, was enlisted to balance the significant peri-operative risks against the hemodynamic and microbiologic benefits of valvular intervention [6]. Consensus was reached to treat for 4 weeks with antibiotics, after which the patient was transferred to another hospital and underwent successful aortic (23-mm Inspiris, bioprosthetic) and mitral (31-mm Mitris, bioprosthetic) valve replacements. No further molecular testing of the explanted valve was performed, as it was deemed unlikely to change management. The patient completed a total of 12 weeks of doxycycline 100 mg twice daily (4 weeks before surgery, 8 weeks after surgery) and 6 weeks of rifampin 300 mg twice daily (4 weeks before surgery, 2 weeks after surgery) at the recommendation of the infectious disease team. To summarize the timeline, the patient was initially admitted for aphasia, endocarditis was diagnosed, and the patient was noted to have positive

Discussion

The Duke criteria, published in 1994 (and later modified) have guided the management of infectious endocarditis for the past 3 decades. However, our understanding of the epidemiology and diagnostics for infectious endocarditis has since evolved. Earlier this year, the International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases proposed modified ISCVID-Duke criteria to include specific microbiological testing for

Infectious endocarditis is one the most common etiologies of acute aortic regurgitation of the native valve [9], with the other being aortic dissection. Infectious endocarditis drives aortic regurgitation via 2 potential mechanisms. First, vegetations can directly disrupt the leaflets, causing either malcoaptation or frank perforation. Second, vegetations can perturb the mechanical integrity of the aortic annulus, leading to leaflet prolapse. Retrograde flow of blood across the aortic valve during diastole increases left ventricular volume. Acutely, this rapidly increases end-diastolic pressure and, in severe cases, causes clinical heart failure. However, because the symptoms of heart failure are nonspecific (eg, dyspnea and fatigue), nonfulminant cases can be difficult to identify. Such cases progress over time, as the ventricle remodels and dilates to accommodate the increased volume. This compensatory remodeling does not produce symptoms per se, but as the left ventricle dilates, its compliance decreases, causing filling pressures to rise. The subsequent left heart failure and pulmonary congestion can then raise pulmonary pressures and precipitate right heart failure. The rise in filling pressures leads to progressive symptoms of congestion, which often sparks the clinical presentation.

The timing of surgical intervention in this case posed a challenge. The American Heart and Stroke Associations (AHA/ASA) recommend deferring elective surgery for at least 6 months from the time of a stroke [10]. However, in cases of infectious endocarditis complicated by major stroke or intracranial hemorrhage requiring valve surgery, the recommendation is shorter: a delay of at least 4 weeks [11]. This difference, based on higher observational mortality rates for surgery performed during this 4-week window [12], attempts to balance the risk of the high-dose anticoagulation required for cardiopulmonary bypass with definitive source control for further cardioembolic events. In this case, a delay would also risk further deterioration in cardiac function, particularly if the disease could not be medically stabilized. However, expedient surgery would fix the proximal cause of heart failure but would still pose high perioperative risk.

In addition to intracranial hemorrhage progression, the other major risk consideration was the pulmonary hypertension, as severe pulmonary hypertension of any etiology is associated with perioperative mortality rates up to 25% [13]. This is in part because high pulmonary pressures limit the capacity of the right ventricle to weather hemodynamic shifts. Perioperatively, right ventricular preload can fluctuate from blood loss, fluid administration, or reduced venous return from positive pressure ventilation. Similarly, right ventricular afterload can vary as changes in alveolar oxygen tension modulate hypoxic vasoconstriction and pulmonary vascular resistance. Under the stress of severe pulmonary hypertension, these acute hemo-dynamic changes can reduce cardiac output and precipitate cardiogenic shock, arrhythmias, or sudden cardiac death [13]. Thus, efforts to maintain the systemic blood pressure (ie, mean arterial pressure) must be finely balanced against the pulmonary hemodynamics.

The etiology of pulmonary hypertension is important to consider, as reversible causes of pulmonary hypertension offer an opportunity for risk reduction. Pulmonary hypertension due primarily to left-sided heart disease (WHO group II) can be greatly improved with diuresis, which decreases pulmonary pressures provided that the pulmonary vasculature has not yet remodeled. Practically speaking, this can be assessed with a repeat right heart catheterization to reassess the filling pressures and pulmonary vascular resistance after diuresis, with the aim to reduce both, as done and observed in the present case.

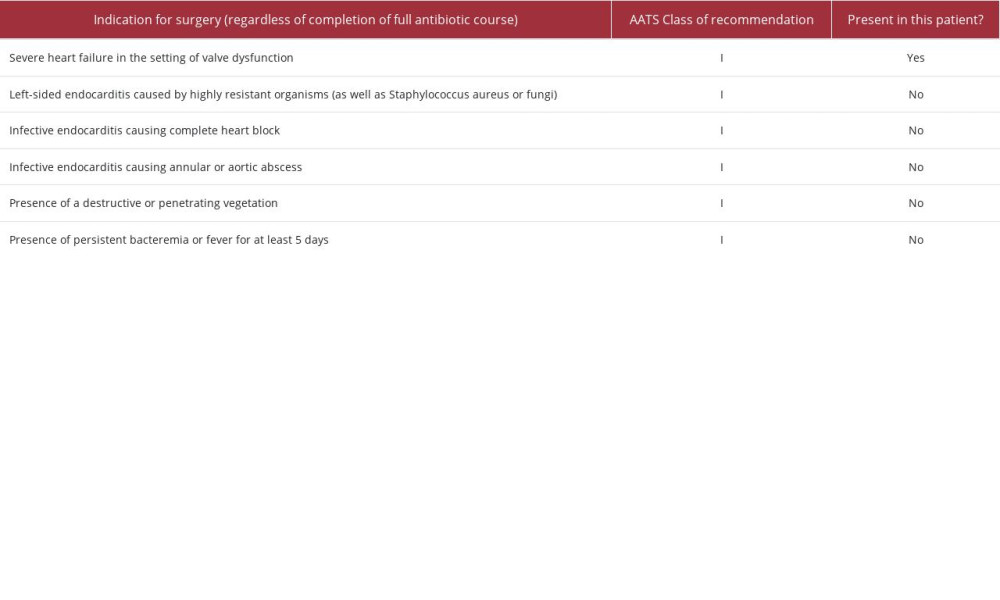

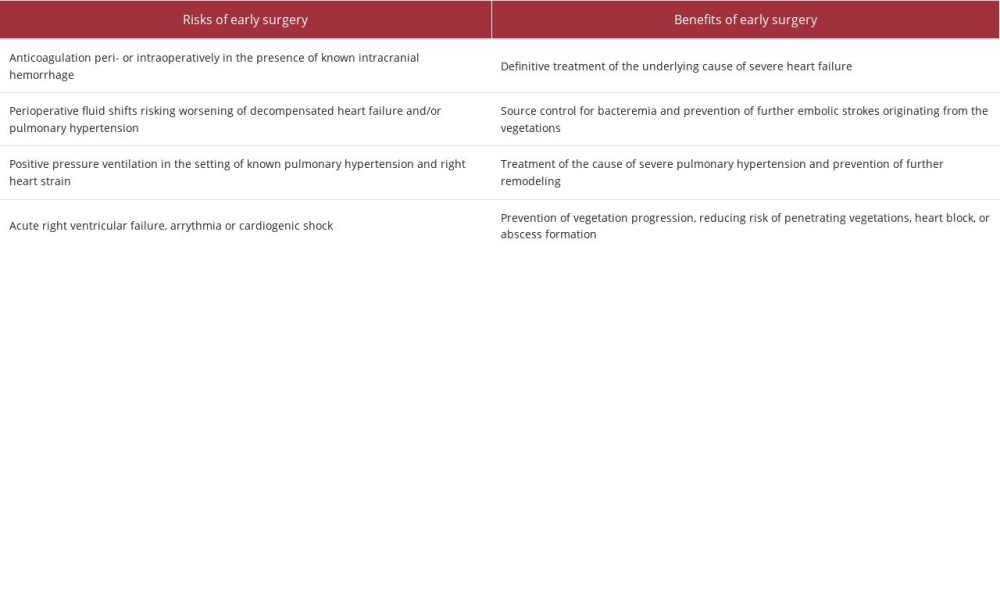

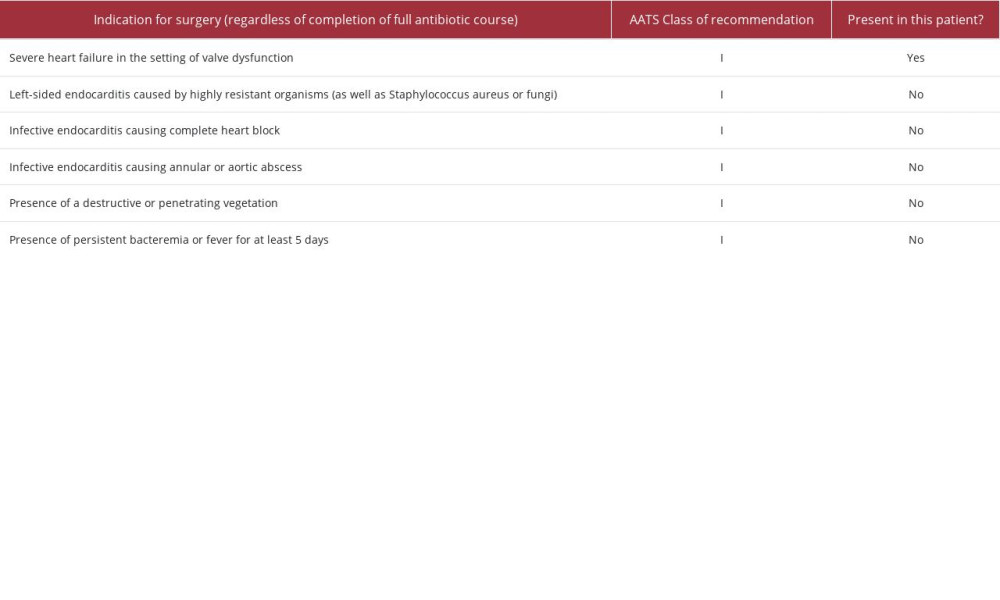

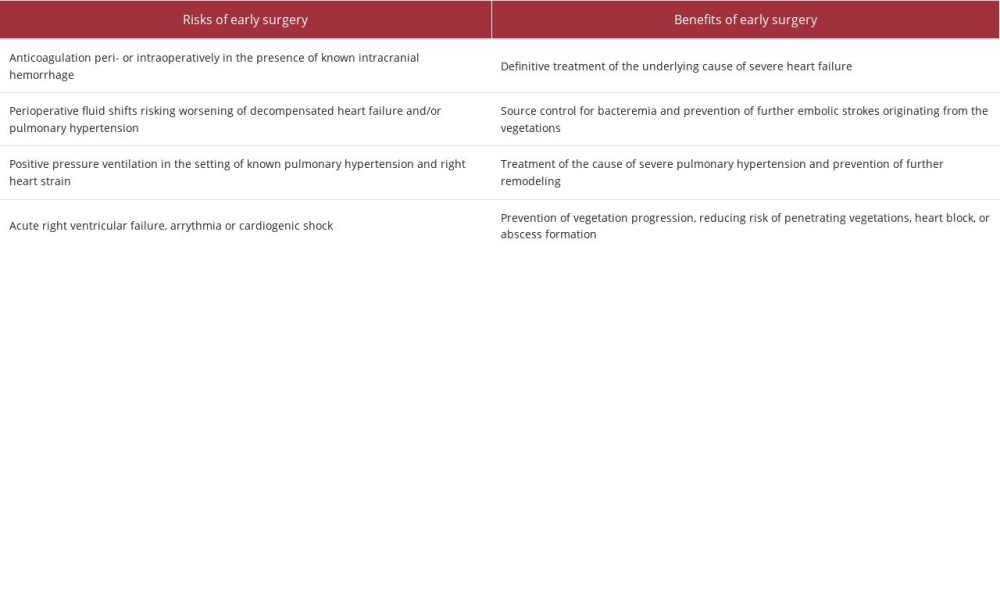

To the extent possible, early identification of infectious endocarditis-induced aortic regurgitation, before the emergence of pulmonary hypertension, decreases perioperative complications. Accordingly, AATS guidelines (Table 1) suggest timing of surgery “within days” when indicated, but this should be weighed against potential complications of early intervention [14], as described above. In our patient, the class I AATS indication was severe heart failure in the setting of valve dys-function, and the complications of both severe pulmonary hypertension and intracranial hemorrhage required multidisciplinary input to determine the optimal timing for valve intervention. After 4 weeks of antibiotics and hemodynamic optimization, given the risks and benefits discussed (Table 2), the patient underwent aortic and mitral valve replacement, with a complication presumed to be atrial flutter. Notably, the management of this case was limited by a diagnostic delay from the incomplete history caused by the aphasia and a prolonged search for next of kin. Further, the patient’s socially complex situation, including a lack of stable housing, created barriers to post-hospital follow-up.

Conclusions

Cases of probable

Figures

References:

1.. Alsmark CM, Frank AC, Karlberg EO: Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2004; 101(26); 9716-21

2.. Chaloner GL, Harrison TG, Birtles RJ: Epidemiol Infect, 2013; 141(4); 841-46

3.. Daly JS, Worthington MG, Brenner DJ: J Clin Microbiol, 1993; 31(4); 872-81

4.. Drancourt M, Mainardi JL, Brouqui P: N Engl J Med, 1995; 332(7); 419-23

5.. Ducruet AF, Hickman ZL, Zacharia BE, Intracranial infectious aneurysms: A comprehensive review: Neurosurg Rev, 2010; 33(1); 37-46

6.. Paciaroni M, Agnelli G, Micheli S, Efficacy and safety of anticoagulant treatment in acute cardioembolic stroke: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials: Stroke, 2007; 38(2); 423-30

7.. Fowler VG, Durack DT, Selton-Suty C, The 2023 Duke-International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases criteria for infective endocarditis: Updating the modified Duke criteria: Clin Infect Dis, 2023; 77(4); 518-26 [Erratum in: Clin Infect Dis. 2023;77(8):1222]

8.. Boodman C, Gupta N: Open Forum Infect Dis, 2023; 10(8); ofad436

9.. Bekeredjian R, Grayburn PA, Valvular heart disease: aortic regurgitation: Circulation, 2005; 112(1); 125-34 [Erratum in: Circulation. 2005;112(9):e124]

10.. Benesch C, Glance LG, Derdeyn CP, Perioperative neurological evaluation and management to lower the risk of acute stroke in patients undergoing noncardiac, nonneurological surgery: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association: Circulation, 2021; 143(19); e923-e46

11.. Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, Infective endocarditis in adults: Diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association: Circulation, 2015; 132; 1435-86

12.. García-Cabrera E, Fernández-Hidalgo N, Almirante B, Neurological complications of infective endocarditis: risk factors, outcome, and impact of cardiac surgery: A multicenter observational study: Circulation, 2013; 127; 2272-84

13.. Minai OA, Yared JP, Kaw R, Perioperative risk and management in patients with pulmonary hypertension: Chest, 2013; 144(1); 329-40

14.. Pettersson GB, Hussain ST, Current AATS guidelines on surgical treatment of infective endocarditis: Ann Cardiothorac Surg, 2019; 8(6); 630-44

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Class I American Association of Thoracic Surgery (AATS) recommendations for early valve replacement in infective endocarditis [14].

Table 1.. Class I American Association of Thoracic Surgery (AATS) recommendations for early valve replacement in infective endocarditis [14]. Table 2.. Summary of the risks and benefits of early surgery in our case.

Table 2.. Summary of the risks and benefits of early surgery in our case. Table 1.. Class I American Association of Thoracic Surgery (AATS) recommendations for early valve replacement in infective endocarditis [14].

Table 1.. Class I American Association of Thoracic Surgery (AATS) recommendations for early valve replacement in infective endocarditis [14]. Table 2.. Summary of the risks and benefits of early surgery in our case.

Table 2.. Summary of the risks and benefits of early surgery in our case. In Press

21 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942921

22 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943346

24 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943560

26 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943893

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250