29 December 2023: Articles

Recurrent Temporal Infections: The Link to Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Unusual clinical course, Challenging differential diagnosis, Unusual or unexpected effect of treatment, Diagnostic / therapeutic accidents, Adverse events of drug therapy, Clinical situation which can not be reproduced for ethical reasons

Syafiqah Aina Shuhardi1BCEF, Mohd Shahrir Mohamed Said2BDE, Thean Yean Kew3BDE, Roszalina Ramli14ADE*DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942163

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e942163

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease with diverse manifestations. The involvement of the musculoskeletal system is very common, and infection is one of the manifestations, which can involve any part of the body. We report a case of a middle-aged woman with recurrent episodes of infection of her left temple.

CASE REPORT: A 51-year old woman was referred to our clinic following failures to eradicate infection on her left temple for 9 months. Examination revealed facial asymmetry, with diffuse non-tender swelling involving her left temple area, which extended to her cheek. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a periosteal reaction of the zygomatic bone. Left temporalis muscle thickening and residual osteomyelitis of the zygomatic bone were also shown by MRI. In view of the unresolved infection with incision and drainage and antibiotics, further blood investigations led to the discovery of SLE. The antinuclear antibody and anti-double-stranded DNA were positive. In addition, low nephelometry markers, C3 (26.7 mg/dL) and C4 (8.24 mg/dL), were observed. This patient was treated with 200 mg of oral hydrochloroquine once daily and 5 mg of oral prednisolone once daily. After 6 months of treatment, the infection subsided, and the structures involved showed remarkable healing. The patient is still taking the same dose and frequency of both drugs at the present time.

CONCLUSIONS: Temporalis pyomyositis and osteomyelitis of the zygomatic bone could be manifestation of SLE disease; however, the involvement of infection cannot be ruled out.

Keywords: Pyomyositis, osteomyelitis, Zygoma, Lupus Erythematosus, Systemic, Temporal Muscle

Background

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterized by multisystem microvascular inflammation with the generation of numerous autoantibodies, particularly the anti-double-stranded DNA antibody and anti-ribonucleic acid antibody (autoantibodies to the ribonucleoprotein, which represent Ro, La, Sm, RNP, Scl-70 and Jo1) [1–3].

The first symptoms of SLE are fatigue and cutaneous and musculoskeletal symptoms [4–9]. On the face, the classical features include generalized maculopapular rash and annular or psoriasiform cutaneous eruption [3].

SLE affects the immune system and predisposes patients to many types of infections. The most common infections involve the respiratory tract, urinary tract, and skin [10]. Infection of the facial skin and the surrounding musculoskeletal area is reported infrequently [11]. While diffuse myalgia is reported by up to 50% of patients with SLE, conditions such as inflammatory myositis are rarely observed [12]. The literature describes that the most commonly reported sites for myositis are the lower limbs [13]. Other possible musculoskeletal pathological conditions detectable in SLE include osteomyelitis [14].

In a recent systematic review including data from 23 countries, including Malaysia, the prevalence and incidence of SLE were shown to be from 3.2 to 159 per 100 000 and 0.3 to 8.7 per 100 000 persons, respectively [15].

While the literature on the prevalence and incidence of SLE are plenty, the opposite was observed in the literature of the incidence and prevalence of osteomyelitis among patients with SLE. A population-based study in Taiwan showed that the incidence rate of osteomyelitis for men with SLE was 255.02 per 100 000 person-years and for women with SLE, 164.41 per 100 000 person-years. When compared with the control group (osteomyelitis patients without SLE), the incidence rate ratio was 8.52 (95% confidence interval (CI) 7.24–10.05) [16].

Treatment of SLE differs based on the severity of the disease. For mild to moderate disease, treatment often involves antimalarial drugs, glucocorticosteroids, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (for arthritis and serositis) and often immunosuppressive therapy for treating persistent disease activity and decreasing glucocorticosteroids use [17]. For patients with severe SLE, immunosuppressive therapy is often initiated alongside the glucocorticosteroids and other drugs, particularly for lupus nephritis [17].

The objective of this case report was to describe the clinical course of pyomyositis and osteomyelitis of the face in a middle-aged Malay woman.

Case Report

IMAGING:

A CT scan (TOSHIBA Aquilion One, Toshiba Medical Systems Co., Ltd, Japan) of the head with contrast was performed initially to rule out bony infection. CT showed focal thickening of the fascia adjacent to the left temporalis muscle (Figure 2). The temporalis muscle and both globes were normal, with no extraconal or intraconal lesions observed. The initial impression was a solid periosteal reaction of the zygoma secondary to chronic congestion, possibly from the previous trauma episode.

MRI (Siemens MRI 3.0 Tesla Verio, Germany) was performed when the initial incision and drainage provided was not successful. The intention was to evaluate the soft tissue adjacent to the zygomatic bone, as well as the bone marrow. Figure 3 shows the axial MR images in (Figure 3A) T1-weighted sequence, (Figure 3B) fat-suppressed post-gadolinium sequence, (Figure 3C) fat-suppressed T2-weighted sequence, and (Figure 3D) subsequent follow-up MRI (during SLE treatment) in T2-weighted sequence.

The findings of MRI included fatty marrow replacement within the left zygomatic bone, prominent periosteal reaction surrounding the left zygomatic bone, and swollen left temporalis muscle and fascia. The findings were suggestive of residual osteomyelitis changes within the left zygomatic bone, with surrounding myositis of the left temporalis muscle.

INCISIONAL BIOPSY:

Since the initial incision and drainage and antibiotic therapy did not resolve the swelling features, which remained similar to the past 9 months (Figure 4), an exploration and incisional biopsy under general anesthesia was performed. Intraoperatively, the left zygomatic body and frontal bone were identified, without any bony perforation or cavitation. Granulation tissue with a sinus tract was observed in the periosteal layer. No pus was observed during the biopsy. The biopsy samples were collected from (1) granulation tissue and (2) bone, including the periosteum and marrow.

The histopathological results from the specimens were not specified. The results showed an area of fibrosis interspersed with some lobules of adipocytes. The tissue was heavily infiltrated by chronic inflammatory cells, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils. This description was in accordance with chronic inflammation with granulation tissue formation.

LABORATORY BLOOD TESTS:

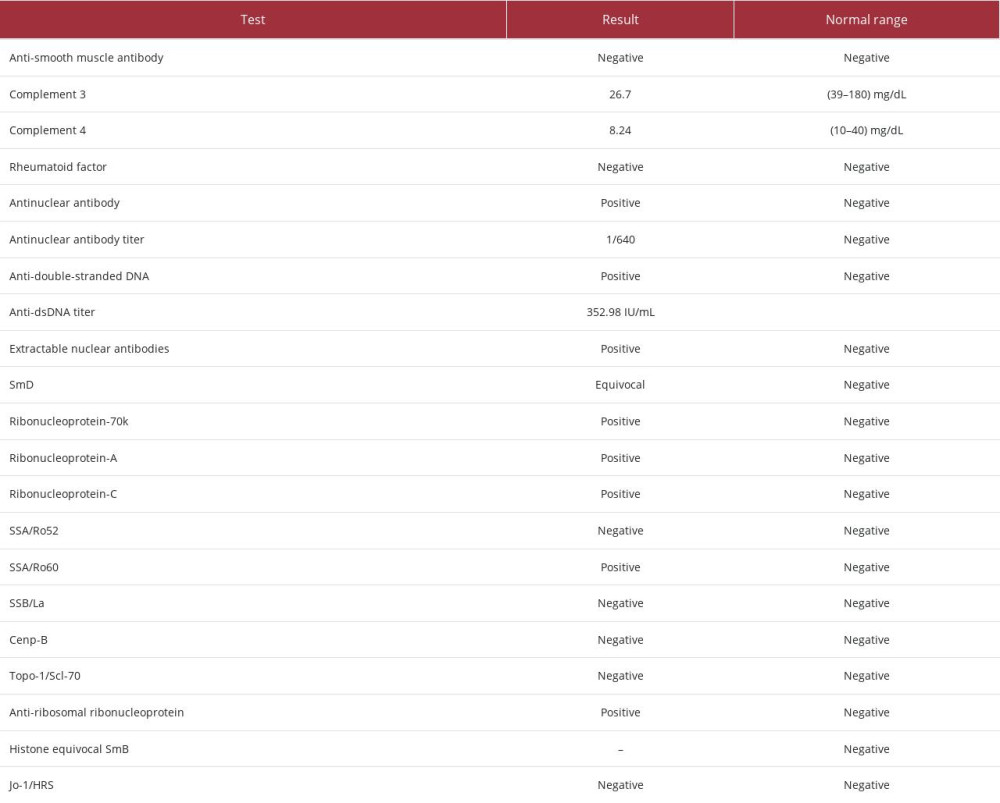

Apart from the routine blood tests, we performed other blood investigations to rule out autoimmune disease. This was performed following the patient’s report of the dry eyes and dry mouth, as well as the unresolved infection issue. The antinu-clear antibodies, complement 3 and 4, anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), extractable nuclear antigen, and rheumatoid factor were investigated alongside the full blood count, renal profile, liver function test, fasting blood glucose, C-reactive protein, and alkaline phosphatase. Urine full examination microscopy examination and urine protein creatinine index were also performed.

The renal profile and fasting blood glucose results were unre-markable. The total protein was slightly raised, at 85 g/L (reference range: 64–83 g/L). The urine full examination microscopy examination and urine protein creatinine index were normal. The results of the immunologic investigation are shown in Table 1. The antinuclear antibodies result was positive, with 1/640 titer, a high titer that indicated high susceptibility for autoimmune diseases. In addition, the titer for the anti-dsDNA was 352.98 IU/mL, indicating the disease was in an active phase. High anti-dsDNA is especially exhibited in patients with musculoskeletal involvement [18].

The positivity of the SSA/Ro60 alone indicated the diagnosis of Sjogren syndrome with the association of SLE [19]. The full blood count results showed chronic mild anemia with hypochromic features and neutropenia and lymphopenia, which are common hematological features in SLE (Table 2).

TREATMENT:

Following the immunological blood investigation, we referred this patient to the SLE team for further treatment. The SLE team confirmed the diagnosis of SLE with Sjogren syndrome. She was referred to the ophthalmology team, and both teams co-managed her condition. She was started on 200 mg oral hydrochloroquine once daily and 5 mg oral prednisolone, also once daily. The ophthalmology team prescribed eye drops for the dryness.

Following a 6-month review, another MRI was performed. The post-treatment MRI showed remarkable improvement, compared with the initial imaging (Figure 3D). The left temporalis muscle and fascia were back to normal size. The surrounding subcutaneous fat was no longer streaky. The periosteal reaction of the adjacent left zygomatic bone remained, but to a lesser degree. The left extraconal inflammatory lesions were significantly reduced in size.

At present, she is continuing the medical treatment of 200 mg oral hydrochloroquine and 5 mg oral prednisolone, both taken once daily, and the eye drops.

Discussion

SIGNIFICANCE:

The significance of myositis in SLE in this patient has yet to be observed. At the time of this writing, this patient remained healthy without any morbidity. It has been shown that myositis in SLE responds well to corticosteroids. This patient is closely monitored for SLE-myositis overlap syndrome, as this could lead to poor prognosis, especially when there is evidence of pulmonary involvement [41].

LIMITATIONS:

One of the most important investigations that could have been performed is a muscle biopsy to confirm the diagnosis of myositis. Following that, immunohistochemical and immunopathological analyses would be performed on the muscle to ascertain the most accurate myositis type [42]. We performed an incisional biopsy of the affected site, and the histopathological examination reported non-specific chronic inflammation.

We did not specify the muscle examination, as myositis was not in our differential diagnoses at that time.

In addition, during the first presentation, a microbiology examination of the pus revealed normal flora. More investigation should be conducted to confirm whether it was aseptic osteomyelitis or whether the bacteria had been eliminated from previous antibiotic treatment.

Conclusions

Chronic facial musculoskeletal infection, such as myositis and osteomyelitis, must be investigated thoroughly in patients with SLE to determine whether the condition is explicitly related to infection or to the disease itself.

Figures

References:

1.. Cozzani E, Drosera M, Gasparini G, Parodi A, Serology of lupus erythematosus: Correlation between immunopathological features and clinical aspects: Autoimmune Dis, 2014; 2014; 321359

2.. Lisnevskaia L, Murphy G, Isenberg D, Systemic lupus erythematosus: Lancet, 2014; 384(9957); 1878-88

3.. Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus: Ann Rheum, 2019; 71(9); 1400-12

4.. Maddison PJ, Is it SLE?: Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol, 2002; 16; 167-80

5.. Hopkinson ND, Doherty M, Powell RJ, Clinical features and race-specific incidence/prevalence rates of systemic lupus erythematosus in a geographically complete cohort of patients: Ann Rheum Dis, 1994; 53; 675-80

6.. Jacobsen S, Petersen J, Ullman S, A multicentre study of 513 Danish patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. II. Disease mortality and clinical factors of prognostic value: Clin Rheumatol, 1998; 17; 478-84

7.. Ozbek S, Sert M, Paydas S, Soy M, Delay in the diagnosis of SLE: The importance of arthritis/arthralgia as the initial symptom: Acta Med Okayama, 2003; 57(4); 187-90

8.. Alonso MD, Martinez-Vazquez F, de Teran TD, Late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in Northwestern Spain: Differences with early-onset systemic lupus erythematosus and literature review: Lupus, 2012; 21; 1135-48

9.. Heinlen LD, McClain MT, Merrill J, Clinical criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus precede diagnosis, and associated autoantibodies are present before clinical symptoms: Arthritis Rheum, 2007; 56; 2344-51

10.. Cojocaru M, Cojocaru IM, Silosi I, Vrabie CD, Manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: Maedica (Bucur), 2011; 6(4); 330-36

11.. Chan AJ, Rai AS, Lake S, Orbital myositis in systemic lupus erythematosus: A case report and literature review: Eur J Rheumatol, 2020; 7(3); 135-37

12.. Bertsias G, Cervera R, Boumpas D, Systemic lupus erythematosus: Pathogenesis and clinical features: EULAR textbook on rheumatic diseases, 2012; 476-505, London, BMJ Group

13.. Sudoł-Szopińska I, Żelnio E, Olesińska M, Update on current imaging of systemic lupus erythematous in adults and juveniles: J Clin Med, 2022; 11(17); 5212

14.. Di Matteo A, Smerilli G, Cipolletta E, Imaging of joint and soft tissue involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: Curr Rheumatol Rep, 2021; 23(9); 73

15.. Fatoye F, Gebrye T, Mbada C, Global and regional prevalence and incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus in low-and-middle income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis: Rheumatol Int, 2022; 42(12); 2097-107

16.. Huang YF, Chang YS, Chen WS, Incidence and risk factors of osteomyelitis in adult and pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus: A nationwide, population-based cohort study: Lupus, 2019; 28(1); 19-26

17.. Tunnicliffe DJ, Singh-Grewal D, Kim S, Diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines: Arthritis Care Res, 2015; 67; 1440-52

18.. Gheita TA, Abaza NM, Hammam N, Anti-dsDNA titre in female systemic lupus erythematosus patients: relation to disease manifestations, damage and antiphospholipid antibodies: Lupus, 2018; 27(7); 1081-87

19.. Yoshimi R, Ueda A, Ozato K, Ishigatsubo Y, Clinical and pathological roles of Ro/SSA autoantibody system: Clin Dev Immunol, 2012; 2012; 606195

20.. Rostić G, Paunić Z, Vojvodić D, Systemic lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis – case report: Srp Arh Celok Lek, 2005; 133(Suppl. 2); 137-40

21.. Liang Y, Leng RX, Pan HF, Ye DQ, Associated variables of myositis in systemic lupus erythematosus: A cross-sectional study: Med Sci Monit, 2017; 23; 2543-49

22.. Bitencourt N, Solow EB, Wright T, Bermas BL, Inflammatory myositis in systemic lupus erythematosus: Lupus, 2020; 29(7); 776-81

23.. Maazoun F, Frikha F, Snoussi M, Systemic lupus erythematosus myositis overlap syndrome: Report of 6 cases: Clin Pract, 2011; 1(4); 189-92

24.. Santosa A, Vasoo S, Orbital myositis as manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus – a case report: Postgrad Med J, 2013; 89(1047); 59

25.. Meesiri S, Pyomyositis in a patient with systemic lupus erythaematosus and a review of the literature: BMJ Case Rep, 2016; 2016; 10.1136/bcr-2016-214809

26.. El Baaj M, Tabache F, Modden K, Pyomyositis: An infectious complication in systemic lupus erythematous: Rev Med Interne, 2010; 31; e4-6

27.. Wasserman PL, Way A, Baig S, Gopireddy DR, MRI of myositis and other urgent muscle-related disorders: Emerg Radiol, 2021; 28(2); 409-21

28.. Bires AM, Kerr B, George L, Osteomyelitis: An overview of imaging modalities: Crit Care Nurs Q, 2015; 38(2); 154-64

29.. Lee YJ, Sadigh S, Mankad K, The imaging of osteomyelitis: Quant Imaging Med Surg, 2016; 6(2); 184-98

30.. Gupta V, Singh I, Goyal S, Osteomyelitis of maxilla – a rare presentation: Case report and review of literature: Int J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2017; 3(3); 771

31.. Jung JY, Suh CH, Infection in systemic lupus erythematosus, similarities, and differences with lupus flare: Korean J Intern Med, 2017; 32(3); 429-38

32.. Wang J, Niu R, Jiang L, The diagnostic values of C-reactive protein and procalcitonin in identifying systemic lupus erythematosus infection and disease activity: Medicine (Baltimore), 2019; 98(33); e16798

33.. Luo KL, Yang YH, Lin YT, Differential parameters between activity flare and acute infection in pediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: Sci Rep, 2020; 10(1); 19913 16

34.. Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, Systemic lupus erythematosus: Clinical and immunologic patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. The European Working Party on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Medicine (Baltimore), 1993; 72(2); 113-24

35.. Apostolopoulos D, Hoi AY, Systemic lupus erythmatosus – when to consider and management options: Aust Fam Physician, 2013; 42(10); 696-700

36.. Shaharir SS, Kadir WDA, Nordin F, Systemic lupus erythematosus among male patients in Malaysia: How are we different from other geographical regions?: Lupus, 2019; 28(1); 137-44

37.. Jasmin R, Sockalingam S, Cheah TE, Goh KJ, Systemic lupus erythematosus in the multiethnic Malaysian population: Disease expression and ethnic differences revisited: Lupus, 2013; 22(9); 967-71

38.. Wu X, Li ZF, Brooks R, Autoantibodies in canine masticatory muscle myositis recognize a novel myosin binding protein-C family member: J Immunol, 2007; 179(7); 4939-44

39.. Hengstman GJ, van Engelen BG, Vree Egberts WT, Myositis-specific autoantibodies: Overview and recent developments: Curr Opin Rheumatol, 2001; 13(6); 476-82

40.. Targoff IN, Idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: Autoantibody update: Curr Rheumatol Rep, 2002; 4; 431-41

41.. Dey B, Rapahel V, Khonglah Y, Jamil M, Systemic lupus erythematosusmyositis overlap syndrome with lupus nephritis: J Family Med Prim Care, 2020; 9(4); 2104-6 30

42.. Vattemi G, Mirabella M, Guglielmi V, Muscle biopsy features of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and differential diagnosis: Auto Immun Highlights, 2014; 5(3); 77-85

Figures

In Press

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943174

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943136

21 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943645

21 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942921

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250