28 October 2020: Articles

Suspected Levetiracetam-Induced Rhabdomyolysis: A Case Report and Literature Review

Unusual or unexpected effect of treatment, Unexpected drug reaction

Imran A. Moinuddin12BEF*DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.926064

Am J Case Rep 2020; 21:e926064

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Levetiracetam (LEV) is an anticonvulsant commonly used for treatment of generalized and partial seizure disorder. Some of the common side effects associated with levetiracetam include somnolence, dizziness, headaches, and mood changes. Rhabdomyolysis and increase in creatine kinase (CK) levels is one of the rarely reported effects of LEV.

CASE REPORT: We report a case of a 22-year-old man admitted for evaluation of new-onset generalized tonic-clonic seizures. The patient was started on levetiracetam 500 mg twice a day, after which his CK levels started to increase, with maximum level of 21 936 IU/L noted on day 5. No improvement in CK levels was observed even with aggressive intravenous hydration. In the absence of any other obvious cause, the persistent elevation in patient’s CK levels was suspected to be due to LEV. Our suspicion was supported by significant decrease in CK levels (from 21 936 IU/L to 11 337 IU/L) after about 30 h of discontinuation of LEV. We reviewed cases of LEV-induced rhabdomyolysis reported in the literature over the last decade and found 13 cases with almost similar correlation between initiation of LEV and increase in CK levels.

CONCLUSIONS: Our case report stresses the importance of close monitoring of CK levels and kidney functions after initiation of LEV, and to consider changing the anticonvulsant medication if CK levels are noted to be significantly high to avoid kidney injury.

Keywords: creatine kinase, rhabdomyolysis, Seizures, Anticonvulsants, Headache, Levetiracetam, young adult

Background

Levetiracetam (LEV) is a second-generation antiepileptic medication being used for the treatment of generalized and partial seizures either as monotherapy or in combination with other antiseizure medications, and for myoclonic seizures as adjunctive therapy [1]. Common adverse effects associated with LEV include fatigue, somnolence, behavioral changes such as irritability and nervousness, minor infections, and thrombocytopenia [2,3]. LEV has rarely been observed to cause elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels, and only a few cases of LEV-associated rhabdomyolysis have been reported in the literature. Rhabdomyolysis involves breakdown of skeletal muscle fibers leading to release of cellular contents including CK and myoglobin into the bloodstream [4]. The most sensitive serologic finding of rhabdomyolysis is an elevated serum CK level [5]. We report a case of 22-year-old man who developed significantly and persistently elevated CK levels after administration of LEV for new-onset generalized tonic-clonic seizure in the absence of any other known underlying cause.

Case Report

A 22-year-old man with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of a new-onset single episode of generalized tonic-clonic seizure at home lasting for about 2–3 min, followed by fall and brief syncopal episode. In the ED, the patient was found to be completely oriented and neurologically intact without postictal confusion. He was administered 1 dose of 500 mg intravenous (IV) LEV in the ED and was admitted for further evaluation and management. The patient was started on oral LEV at 500 mg twice a day. Imaging studies, including computed tomography of the head and magnetic resonance imaging of the head, were unremarkable. Electroencephalogram (EEG) was un-remarkable and did not show any focus of epileptiform activity. Neurology consultation was requested and although this was the patient’s first seizure episode in his lifetime, continuation of LEV was recommended because of previously suspected seizurelike symptoms in the patient’s history. The CK level obtained 10 h after hospital admission (and 8 h after first LEV dose) was found to be slightly elevated at 771 IU/L. The patient’s mildly elevated CK level was presumed to be due to rhabdomyolysis secondary to the seizure episode. IV fluids were initiated and CK levels were monitored. Despite aggressive IV hydration at 150–200 mL/h for almost 72 h, CK levels continued to rise and reached a level above 20 000 IU/L on day 5. The patient’s serum myoglobin was elevated at 594 ng/mL (normal: 28–72 ng/mL), but there was no evidence of acute kidney injury or myoglobinuria. In the absence of any obvious reason to explain this unexpected and persistent increase in CK level, LEV was then considered to be the cause of rhabdomyolysis in this patient. LEV was discontinued on day 5, with CK levels peaking to 21 936 IU/L about 12 h after the last LEV dose, followed by significant decrease in CK level to 11 337 IU/L the next day (Figure 1). Our suspicion of LEV-induced rhabdomyolysis was strongly supported by the following facts: (1) the patient was not on any other medications; (2) he remained seizure free since his hospital admission; (3) he had no known underlying musculoskeletal disorder; (4) the patient denied any recent viral respiratory tract or gastrointestinal infection; (5) the patient’s serum electrolytes, including phosphorus, calcium, and potassium, were within normal limits and his urine drug screen was negative for cocaine/amphetamines; (6) his CK levels declined significantly from 21 936 IU/L to 11 337 IU/L within 24 h of discontinuation of LEV. Throughout his hospital stay, the patient did not complain of myalgias; he remained neurologically intact and seizure free. We did not check the patient for genetic musculoskeletal or mitochondrial disorders as the patient declined family history of musculoskeletal disorders. The patient was discharged home in stable condition on day 6 without antiepileptic medication. The neurologist’s decision to monitor the patient off antiepileptic medication was based on the fact that this was the patient’s first seizure episode, in addition to having a normal EEG during his hospital stay. The patient was advised to follow up with the neurologist an as outpatient within 1–2 weeks of discharge, and he reported no further seizure episodes. Repeat EEG after 14 days of hospital discharge also did not show any epileptiform activity. The CK level was repeated 8 days after hospital discharge (9 days after discontinuation of LEV) and it was found to be 330 IU/L, further supporting our provisional diagnosis.

Discussion

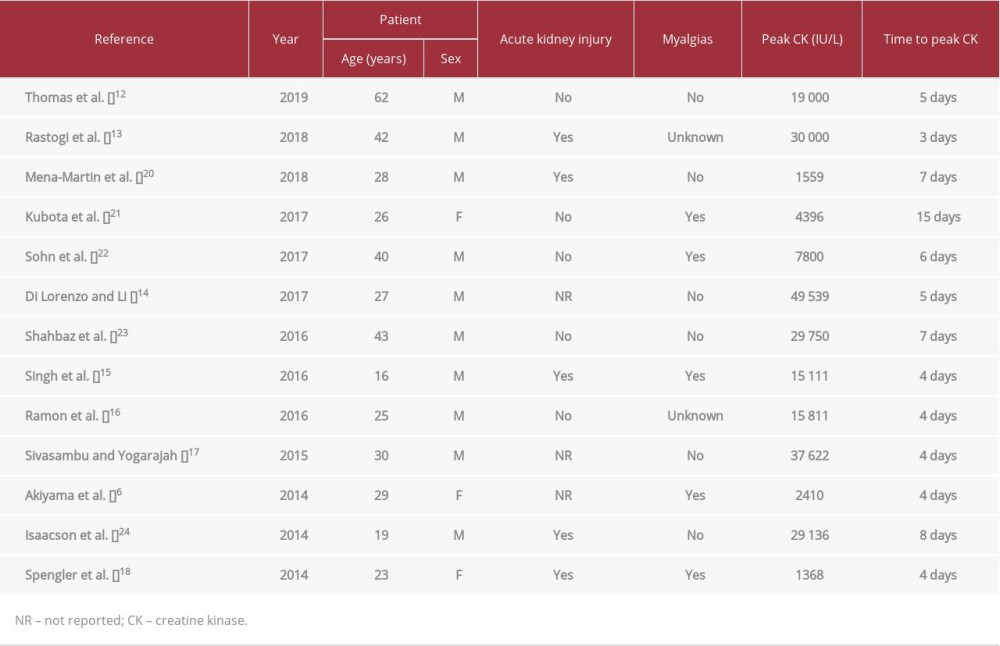

LEV is a second-generation antiepileptic medication that was approved in the United States in late 1990s and is currently being used for the treatment of generalized and partial seizures [6]. LEV promotes the release of synaptic neurotransmitter by binding to synaptic vesicle 2A (SV2A) protein [7] that is expressed widely in the brain and selectively in slow muscle fiber motor nerve terminals [8]. It does not possess cyto-chrome P-450 activity and therefore has minimal interaction with other drugs and has been reported to be fairly well tolerated [9]. Rhabdomyolysis is one of the rarely observed/reported side effects of LEV despite its widespread use. Some of the common causes of rhabdomyolysis include trauma (motor vehicle accident, crush injuries), strenuous exercise, seizures, hypothermia, malignant hyperthermia, electrolyte imbalances (hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, hypophosphatemia), autoimmune disorders such as polymyositis and dermatomyositis, and certain genetic disorders such as McArdle disease, Tarui disease, Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies, mitochondrial disorders, and certain drugs [10]. In addition to LEV, Kaufman and Choy in 2012 reported another anticonvulsant, pregabalin, as a cause of rhabdomyolysis when used in combination with simvastatin [11]. The patient in our case demonstrated a temporal relationship between exposure to LEV and onset of elevated CK levels followed by improvement in CK levels upon discontinuation of the medication. We reviewed cases of LEV-induced rhabdomyolysis reported in the literature over the last decade (Table 1).

Of interest, most of the reported cases of LEV-induced rhabdomyolysis were observed in young and adolescent patients between the ages of 19 and 30 years, with only 1 patient being above the age of 60 years [12]. Peak CK levels observed in these cases were highly variable and ranged between 1368 IU/L and 49 539 IU/L. The difference in observed peak CK levels among the reported cases could likely be related to difference in muscle mass of the patients. Our patient weighed 64 kg and had a muscular body, which likely explains the significant increase in CK levels. In almost all of the cases included in our literature review, elevation in CK level was observed within 12–36 h of initiation of LEV, suggesting the need for close observation, particularly during the initial treatment phase. In most of the reported cases [6,12–18], the time elapsed from initiation of LEV to peak CK elevation was noted to be 3–5 days, after which the medication was discontinued, leading to improvement in CK levels. Symptomatic rhabdomyolysis (back pain, muscle aches) was reported in 5 of 13 cases; our patient, however, did not develop any symptoms of rhabdomyolysis.

The patient reported in our case continued to have increasing CK levels up to 5 days after his single seizure episode, which further supported our presumptive diagnosis of LEV-induced rhabdomyolysis as opposed to seizure-related rhabdomyolysis. Brigo et al. suggested that seizure-related rhabdomyolysis is usually associated with slight elevation of CK levels, with peak level noted at 36–40 h [19].

The exact mechanism by which LEV causes rhabdomyolysis is not clear. One proposed theory is the interaction of LEV with SV2A protein in motor nerve terminals of slow muscle fibers, causing enhanced cholinergic neurotransmission and increased stress in muscles, leading to rhabdomyolysis [8].

Conclusions

Although LEV has been known to be well tolerated, it has the potential to cause rhabdomyolysis in some patients. Therefore, clinicians need to be aware and vigilant about this rare side effect of LEV, particularly during the early phase of treatment.

We recommend close monitoring of CK levels and kidney functions after initiation of LEV, and to consider changing the anti-convulsant medication if CK levels are noted to be significantly high to avoid kidney injury. Our case report also emphasizes that rhabdomyolysis may be totally asymptomatic (as in our patient), and therefore close monitoring of CK levels should be considered while in the hospital and as an outpatient if the patient is discharged home on day 3–5 of initiation of LEV.

References:

1.. Lyseng-Williamson KA, Levetiracetam: A review of its use in epilepsy: Drugs, 2011; 71(4); 489-514

2.. Trinka E, Dobesberger J, New treatment options in status epilepticus: A critical review on intravenous levetiracetam: Ther Adv Neurol Disord, 2009; 2(2); 79-91

3.. Verrotti A, Prezioso G, Di Sabatino F, The adverse event profile of levetiracetam: A meta-analysis on children and adults: Seizure, 2015; 31; 49-55

4.. Zutt R, van der Kooi AJ, Linthorst GE, Rhabdomyolysis: Review of the literature: Neuromuscul Disord, 2014; 24(8); 651-59

5.. Huerta-Alardín AL, Varon J, Marik PE, Bench-to-bedside review: Rhabdomyolysis – an overview for clinicians: Crit Care, 2005; 9(2); 158-69

6.. Akiyama H, Haga Y, Sasaki N, A case of rhabdomyolysis in which levetiracetam was suspected as the cause: Epilepsy Behav Case Rep, 2014; 2; 152-55

7.. Lynch BA, Lambeng N, Nocka K, The synaptic vesicle protein SV2A is the binding site for the antiepileptic drug levetiracetam: Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2004; 101(26); 9861-66

8.. Carnovale C, Gentili M, Antoniazzi S, Levetiracetam induced rhabdomyolysis: Analysis of reports from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database: Muscle Nerve, 2017; 56(6); E176-78

9.. Patsalos PN, Pharmacokinetic profile of levetiracetam: Toward ideal characteristics: Pharmacol Ther, 2000; 85(2); 77-85

10.. Torres PA, Helmstetter JA, Kaye AM, Kaye AD, Rhabdomyolysis: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment: Ochsner J, 2015; 15(1); 58-69

11.. Kaufman MB, Choy M, Pregabalin and simvastatin: First report of a case of rhabdomyolysis: P T, 2012; 37(10); 579-95

12.. Thomas L, Mirza MMF, Shaikh NA, Ahmed N, Rhabdomyolysis: A rare adverse effect of levetiracetam: BMJ Case Rep, 2019; 12(8); e230851

13.. Rastogi V, Singh D, Kaur B, Rhabdomyolysis: A rare adverse effect of levetiracetam: Cureus, 2018; 10(5); e2705

14.. Di Lorenzo R, Li Y, Rhabdomyolysis associated with levetiracetam administration: Muscle Nerve, 2017; 56(1); E1-2

15.. Singh R, Patel DR, Pejka S, Rhabdomyolysis in a hospitalized 16-year-old boy: A rarely reported underlying cause: Case Rep Pediatr, 2016; 2016; 7873813

16.. Ramon M, Tourteau E, Lemaire N, HyperCKemia induced by levetiracetam: Presse Med, 2016; 45(10); 943-44

17.. Sivasambu B, Yogarajah M, Levetiracetam induced rhabdomyolysis: Crit Care, 2015; 148(4); 277A

18.. Spengler DC, Montouris GD, Hohler AD, Levetiracetam as a possible contributor to acute kidney injury: Clin Ther, 2014; 36(8); 1303-6

19.. Brigo F, Igwe SC, Erro R, Postictal serum creatine kinase for the differential diagnosis of epileptic seizures and psychogenic non-epileptic seizures: A systematic review: J Neurol, 2015; 262(2); 251-57

20.. Mena-Martin FJ, Gutierrez-Garcia A, Martin-Escudero JC, Fernandez-Arconada O, Acute kidney injury and creatine kinase elevation after beginning treatment with levetiracetam: Eur Neurol Rev, 2018; 13(2); 113-15

21.. Kubota K, Yamamoto T, Kawamoto M, Levetiracetam-induced rhabdomyolysis: A case report and literature review: Neurol Asia, 2017; 22(3); 275-78

22.. Sohn SY, Kim JG, Kim DH, Repeated occurrence of hyperCKemia after levetiracetam administration: EC Neurol, 2017; 8(5); 150-54

23.. Shahbaz N, Khan SA, Younus SM, Levetiracetam induced increase in creatine phosphokinase levels: J Coll Physicians Surg Pak, 2017; 27(3); S63-64

24.. Isaacson JE, Choe DJ, Doherty MJ, Creatine phosphokinase elevation exacerbated by levetiracetam therapy: Epilepsy Behav Case Rep, 2014; 2; 189-91

In Press

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943010

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943687

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943070

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943370

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250