18 August 2021: Articles

A 55-Year-Old Japanese Man with Multiple Sclerosis Diagnosed with Disseminated Tuberculosis Identified by Liver Function Abnormalities: A Case Report

Challenging differential diagnosis, Diagnostic / therapeutic accidents, Management of emergency care, Rare disease, Adverse events of drug therapy, Educational Purpose (only if useful for a systematic review or synthesis)

Akio Miyasaka1ABCDEF*, Shinichirou Sato2BCD, Tomoyuki Masuda3CD, Yasuhiro Takikawa1ADOI: 10.12659/AJCR.931369

Am J Case Rep 2021; 22:e931369

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Reactivation of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) is a recognized complication of immunosuppressive treatment. However, immunosuppressed patients are also at risk of hematogenous disseminated spread from a primary infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. This report presents the case of a 55-year-old Japanese man with a 12-year history of multiple sclerosis who was hospitalized with worsening neurological symptoms and was diagnosed with disseminated tuberculosis identified by abnormalities on liver function test results.

CASE REPORT: A 55-year-old Japanese man was admitted to our hospital for the treatment of multiple sclerosis with worsening symptoms. He showed mild liver dysfunction at the time of admission. A laparoscopy and biopsy were performed to identify the cause of the liver dysfunction, which was the only positive finding. The liver surface was studded with yellowish-white nodular lesions. Histological examination of a liver biopsy specimen revealed a granuloma without caseous necrosis. The patient was suspected of having tuberculosis. Although the results of an interferon-γ-releasing assay were indeterminate, asymptomatic disseminated tuberculosis was diagnosed from the serum adenosine deaminase levels, a caseating granuloma in the cervical lymph node, detection of acid-fast bacilli DNA in the cervical lymph nodes on polymerase chain reaction, and tuberculin skin test findings. Anti-tuberculosis treatment led to improvement in the liver function test findings.

CONCLUSIONS: This case has highlighted that tuberculosis may have an atypical presentation in the immunosuppressed patient. In addition to the reactivation of LTBI, hematogenous spread of primary tuberculosis may result in disseminated disease involving multiple organs and requiring emergency treatment.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Tuberculosis, Hepatic, Tuberculosis, Miliary, Granuloma, Japan, Liver Diseases, Multiple Sclerosis

Background

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by

In addition, the reactivation of LTBI is a recognized complication of immunosuppressive treatment; however, immunosup-pressed patients are also at risk of hematogenous disseminated spread from primary infection with

Case Report

A 55-year-old Japanese man had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) and started receiving azathioprine and prednisolone 12 years previously. On this occasion, he was admitted to our hospital to receive interferon (IFN) treatment for his MS because of worsening symptoms.

On admission, his body temperature was 36.8°C. A chest and abdominal physical examination revealed no remarkable changes, and the patient had a lymphadenopathy in his neck. A neurological examination revealed paraplegia and sensory disturbance of both lower limbs. The chest radiography (Figure 1A, 1B) and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings were unremarkable, but a spinal MRI scan showed a demyelinating lesion in the second and third cervical spinal cords and dorsal column of the thoracic spinal cord.

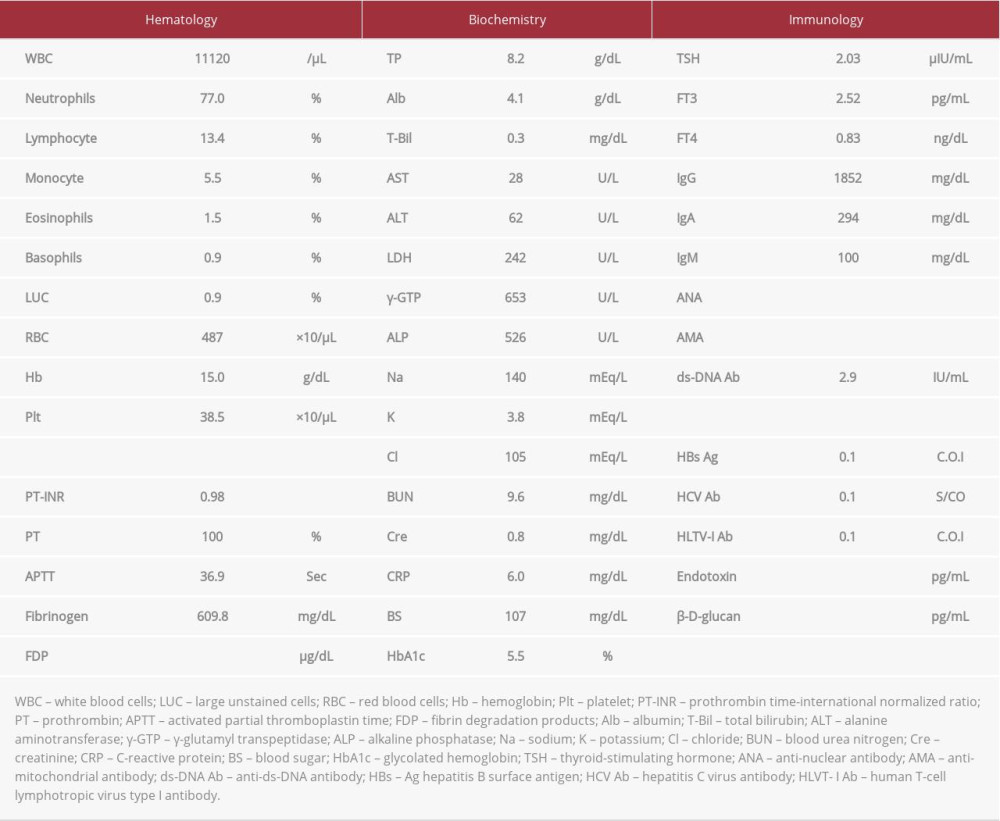

Laboratory testing at admission revealed mild elevations in the serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels (Table 1). After admission, it was revealed that the patient had stopped taking azathioprine and prednisolone at his own decision 5 years previously. The administration of the drugs was restarted, and the IFN treatment was postponed.

The patient also consulted our division for further examination of his hepatic dysfunction. The serologic findings for hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C virus antibody, human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I antibody, Epstein-Barr virus marker, and cytomegalovirus marker were all negative. Antinuclear and antimitochondrial antibodies were also negative. No hepatic masses were observed on ultrasonography (US) or computed tomography (CT) (Figure 1C, 1D). Furthermore, no findings were observed in the imaging examination (CT and US) of the biliary tract and gall bladder.

Laparoscopy was performed on the 19th hospital day to search for causes of the liver dysfunction. The findings showed that the surface of the liver was studded with yellowish-white nodular lesions (Figure 2A, 2B). Histological examination of a liver biopsy specimen revealed a granuloma without caseous necrosis (Figure 2C). Ziehl-Neelsen staining was negative for acid-fast bacilli. We searched for diseases that could cause granulomas, particularly sarcoidosis. However, the ophthalmologic, thoracic, and abdominal lymph node findings, as well as the serum angiotensin-converting enzyme and lysozyme evaluation findings failed to suggest a diagnosis of sarcoidosis. The patient was therefore strongly suspected as having TB.

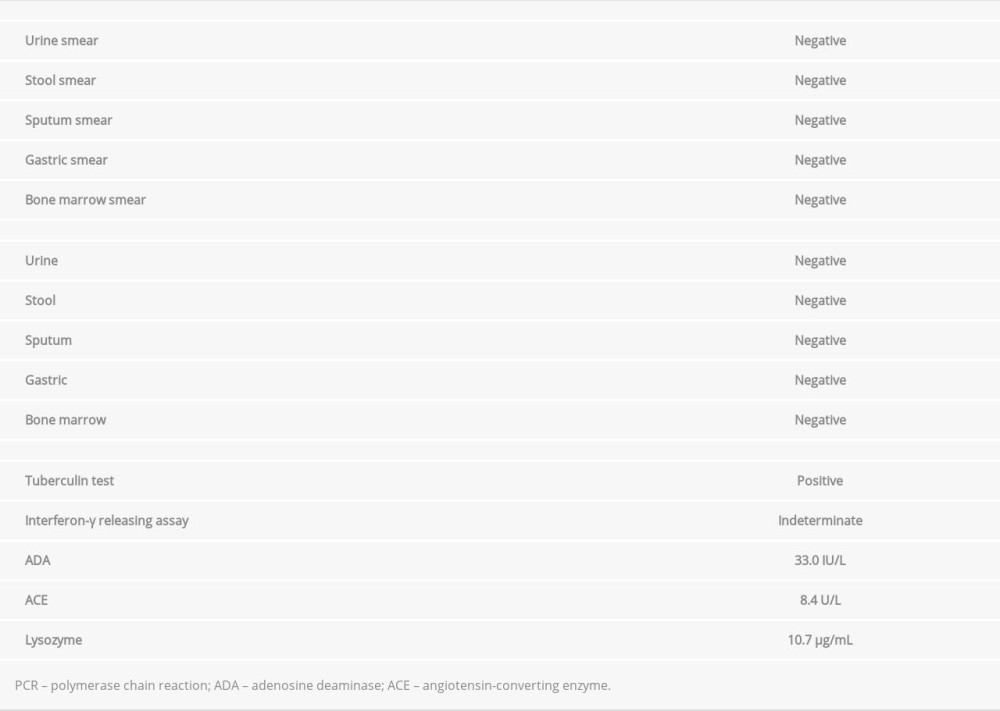

The IFN-γ releasing assay results were inconclusive. Sputum, urine, gastric, and bone-marrow smear specimens were negative for acid-fast bacilli, although serum adenosine deaminase (ADA) level was high (Table 2). Therefore, to further examine and confirm the presence of disseminated TB, a cervical lymph node biopsy was performed on the 70th hospital day. On histological examination, the cervical lymph node showed no evidence of malignancy or lymphoma but a granuloma with caseous necrosis was found (Figure 2D). Ziehl-Neelsen staining showed no acid-fast bacilli, but acid-fast bacilli were detected in the cervical lymph nodes by PCR. In addition, the result of a tuberculin skin test was positive, with a 46-mm wheal. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of disseminated TB. In particular, the diagnosis was based on the finding of a granuloma with caseous necrosis in the cervical lymph node and the detection of acid-fast bacilli DNA in the cervical lymph node by PCR. Furthermore, a granuloma without caseous necrosis in the liver tissue, elevation in ADA levels, and a positive tuberculin skin test supported the diagnosis of disseminated TB.

The patient was initially given a regimen of isoniazid (300 mg/day), rifampicin (450 mg/day), pyrazinamide (1 g/day), and streptomycin (0.75 g intramuscular injection, 3 times a week). Twenty days after the administration of this treatment regimen, his serum ALT, γ-GTP, and ALP levels had decreased to normal. After 1 month, streptomycin was replaced with ethambutol due to concerns regarding an auditory disorder. After 2 months of undergoing the 4-drug antituberculotic therapy, pyrazinamide and ethambutol were discontinued, and treatment with isoniazid and rifampicin only was continued. Approximately 6 months after the initiation of the therapy, the patient’s liver function test results (ALT, 33 U/L) showed improvement (Figure 3).

Discussion

Disseminated TB accounts for <2% of all TB cases [5]. Moreover, hepatic TB is considered a rare clinical entity. It is classified into 5 forms as follows: secondary to disseminated, granulomatous hepatitis, nodular, ductal, and nodal [7]. The disseminated form is the most common, and the present case was categorized as secondary to disseminated TB without pulmonary TB.

The patient had no history of diabetes mellitus or the use of azathioprine and corticosteroids prior to the present illness. No apparent risk factors of TB were observed [8] with the exception of MS, an autoimmune condition, which can be considered an immunocompromised state. In particular, the reactivation of LTBI can be triggered by therapy for MS [9], but it was observed in the patient regardless of MS treatment. Therefore, monitoring for LTBI should be implemented in patients with MS. Furthermore, the patient’s systematic symptoms were less severe than would be expected in patients with disseminated TB, which is typically associated with a fever and more marked night sweats and weight loss [10–12]. In addition, disseminated TB has a characteristic pattern on chest radiography [13], but all chest radiography findings in this patient were normal. Generally, making a diagnosis of disseminated TB without pulmonary involvement is difficult because of the lack of a localizing sign and the presence of normal chest radiography. However, disseminated TB should be suspected in immunocompromised patients [6]. ALP is usually disproportionately elevated in hepatic TB [7]. In the present case, although biliary tract enzyme levels (ALP and γ-GTP) were elevated, no findings were observed on radiologic examination (CT and US) of the biliary tract and gall bladder. Only the liver function test after admission revealed an abnormality, so we performed a laparoscopy to identify the etiology of the liver dysfunction. The characteristic laparoscopic findings of hepatic TB are a cheesy white or sometimes chalky white color on the liver surface, with irregular nodules of varying sizes [14], to which the present patient’s laparoscopic findings were strikingly similar. Histologically, most granulomas are usually located near the portal tract, with only mild hepatic function perturbation, so most patients are minimally symptomatic or asymptomatic [15]. In the liver biopsy specimens in this case, the granuloma was found in the central venous area. A discrepancy between the location of the granuloma and the symptoms was observed. However, other granulomas may be present near the portal tract.

As for the diagnosis of hepatic TB, in liver biopsy specimens, an epithelioid granuloma with caseous necrosis must be present or

We selected a 6-month regimen (2 months of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and streptomycin/ethambutol, followed by 4 months of isoniazid and rifampicin) as the initial treatment for disseminated TB [22]. This anti-TB treatment was effective in our patient and led to the improvement of the liver function test findings. Thus, although we found no histological evidence of treatment efficacy at the end of the regimen, the improvement of the liver function test findings led us to presume the absence of granulomas.

Conclusions

This case demonstrates that TB may have an atypical presentation in immunosuppressed patients. In addition to the reactivation of LTBI, immunosuppressed patients may also present with a hematogenous spread of primary TB, which may result in disseminated disease involving multiple organs and requiring emergency treatment.

Figures

References:

1.. : World Health Organization (WHO) Global tuberculosis report 2019, 2019, Geneva, WHO https://www.who.ito/tb/publications/global_report/en/

2.. Epstein DJ, Dunn J, Deresinski S, Infectious complications of multiple sclerosis therapies: Implications for screening, prophylaxis, and management: Open Forum Infect Dis, 2018; 5(8); 174

3.. Fanning A, Tuberculosis: 6. Extrapulmonary disease: Can Med Assoc J, 1999; 160(11); 1597-603

4.. Cunha BA, Krakakis J, McDermott BP, Fever of unknown origin (FUO) caused by miliary tuberculosis: diagnostic significance of morning temperature spikes: Heart Lung, 2009; 38(1); 77-82

5.. Sharma SK, Mohan A, Miliary tuberculosis: Microbiol Spectr, 2017; 5(2); 10

6.. Khan FY, Review of literature on disseminated tuberculosis with emphasis on the focused diagnostic workup: J Family Community Med, 2019; 26(2); 83-91

7.. Evans PR, Mourad MM, Dvorkin L, Bramhall SR, Hepatic and Intra-abdominal Tuberculosis: 2016 Update: Curr Infect Dis Rep, 2016; 18(12); 45-52

8.. Davies PD, Risk factors for tuberculosis: Monaldi Arch Chest Dis, 2005; 63(1); 37-46

9.. Sirbu CA, Dantes E, Plesa CF, Active pulmonary tuberculosis triggered by interferon beta-1b therapy of multiple sclerosis: Four case reports and a literature review: Medicina (Kaunas), 2020; 56(4); 202

10.. Bofinger JJ, Schlossberg D, Fever of unknown origin caused by tuberculosis: Infect Dis Clin North Am, 2007; 21(4); 947-62

11.. Goto M, Koyama H, Takahashi O, Fukui T, A retrospective review of 226 hospitalized patients with fever: Intern Med, 2007; 46(1); 17-22

12.. Mert A, Arslan F, Kuyucu T, Miliary tuberculosis: Epidemiological and clinical analysis of large-case series from moderate to low tuberculosis endemic country: Medicine, 2017; 96(5); e5875

13.. Ray S, Talukdar A, Kundu S, Diagnosis and management of miliary tuberculosis: Current state and future perspectives: Ther Clin Risk Manag, 2013; 9; 9-26

14.. Alvarez SZ, Hepatobiliary tuberculosis: J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 1998; 13(8); 833-39

15.. Wu Z, Wang WL, Zhu Y, Diagnosis and treatment of hepatic tuberculosis: Report of five cases and review of literature: Int J Clin Exp Med, 2013; 6(9); 845-50

16.. Guckian JC, Perry JE, Granulomatous hepatitis: An analysis of 63 cases and review of the literature: Ann Intern Med, 1966; 65(5); 1081-100

17.. Lamps LW, Hepatic granulomas: A review with emphasis on infectious causes: Aech Pathol Lab Med, 2015; 139(7); 867-75

18.. Diaz ML, Herrera T, Lopez-Vidal Y, Polymerase chain reaction for the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in tissue and assessment of its utility in the diagnosis of hepatic granulomas: J Lab Clin Med, 1996; 127(4); 359-63

19.. , [Guidelines for the use of interferon-γ release assay by Prevention Committee, the Japanese Society for Tuberculosis.]: Kekkaku, 2014; 89; 717-25 [in Japanese]

20.. Bélard E, Semb S, Ruhwald M, Prednisolone treatment affects the performance of the QuantiFERON Gold In-tube test and the tuberculin skin test in patients with autoimmune disorders screened for latent tuberculosis infection: Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2011; 17(11); 2340-49

21.. Shovman O, Anouk M, Vinnitsky N, QuantiFERON-TB Gold in the identification of latent tuberculosis infection in rheumatoid arthritis: A pilot study: Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2009; 13(11); 1427-32

22.. , Review of “Standards for tuberculosis care” – 2018: Kekkaku, 2018; 93(1); 61-68

Figures

In Press

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943010

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943687

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943070

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943370

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250