06 December 2021: Articles

When Zebras Collide: A Case of Synchronous Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome and Pheochromocytoma

Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Kaiwen ZhuDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.934137

Am J Case Rep 2021; 22:e934137

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Pheochromocytoma is a rare catecholamine-secreting tumor arising from chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla. Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) pattern is a rare congenital cardiac conduction disorder in which 1 or more accessory pathways connects the atria and ventricles, bypassing the atrioventricular (AV) node. Patients with this type of accessory pathway who also experience pre-excitation evoked arrhythmias have what is termed WPW syndrome. Here, we present a patient with a WPW pattern who underwent surgical resection of a pheochromocytoma, review considerations relating to the perioperative management, and briefly summarize the hormonal effects of pheochromocytoma in a patient with a WPW accessory pathway.

CASE REPORT: A man in his early 30’s with a history of hypertension developed shortness of breath with palpitations, was noted to have delta waves on electrocardiogram (ECG), and was given a diagnosis of WPW syndrome. Six years later, he developed headache, chest pain, and flank discomfort in addition to his daily palpitations and shortness of breath. Plasma catecholamine levels were measured and found to be elevated, and imaging studies noted the presence of a large right-sided adrenal mass, consistent with a pheochromocytoma. A decision was made to proceed with a laparoscopic right adrenalectomy, which was successful and uneventful. Through the 30-day postoperative period, he reported no further episodes of symptomatic palpitations for the first time in several years.

CONCLUSIONS: To the best of our knowledge, this is only the fourth case in the literature describing pheochromocytoma with co-existing WPW syndrome. In our case, resection of the pheochromocytoma ameliorated the patient’s chronic WPW-related tachyarrhythmia.

Keywords: Adrenalectomy, Perioperative Medicine, Pheochromocytoma, Tachycardia, Atrioventricular Nodal Reentry, Adrenal Gland Neoplasms, Animals, Electrocardiography, Equidae, Humans, Male, Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome

Background

Pheochromocytoma is a rare catecholamine-secreting tumor arising from chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla, with an incidence rate of 0.1–0.6% in patients with hypertension [1]. The WPW pattern is a finding identified on ECG by a shortened PR interval together with the presence of a delta wave, often described as a “slurring” of the upstroke in the QRS complex. This ECG observation is a consequence of a rare congenital cardiac conduction disorder in which 1 or more accessory pathways connect the atria and ventricles, bypassing the AV node [2]. Electrical impulse conduction through an accessory pathway may occur in 1 of 2 orientations: orthodromic (retrograde conduction from the ventricles up to the atria) or antidromic (antegrade conduction from the atria down to the ventricles). In either case, this rogue conduction can result in ventricular pre-excitation leading to re-entrant supraventricular tachyarrhythmias, described clinically as the WPW syndrome [2]. In rare cases, pheochromocytoma can co-exist with WPW pattern, but to the best of our knowledge there are only 3 cases reported in the literature [3–5]. Not surprisingly, there is likewise little evidence regarding peri-operative management and clinical outcomes of patients with these co-existing disease entities. Here, we describe the case of a patient with a previously identified WPW pattern who underwent a successful surgical resection of a pheochromocytoma.

Case Report

A 30-year-old man developed new-onset palpitations which he described as “racing” and were associated with shortness of breath. His past medical history prior to this was significant for a diagnosis of hypertension at age 15 years, for which he had not received any medical follow-up. At the onset of his palpitations, he sought the evaluation of a cardiologist, who identified a WPW pattern on his electrocardiogram and subsequently diagnosed him with the WPW syndrome. An accessory conduction bypass tract catheter ablation was recommended at that time, but the patient declined.

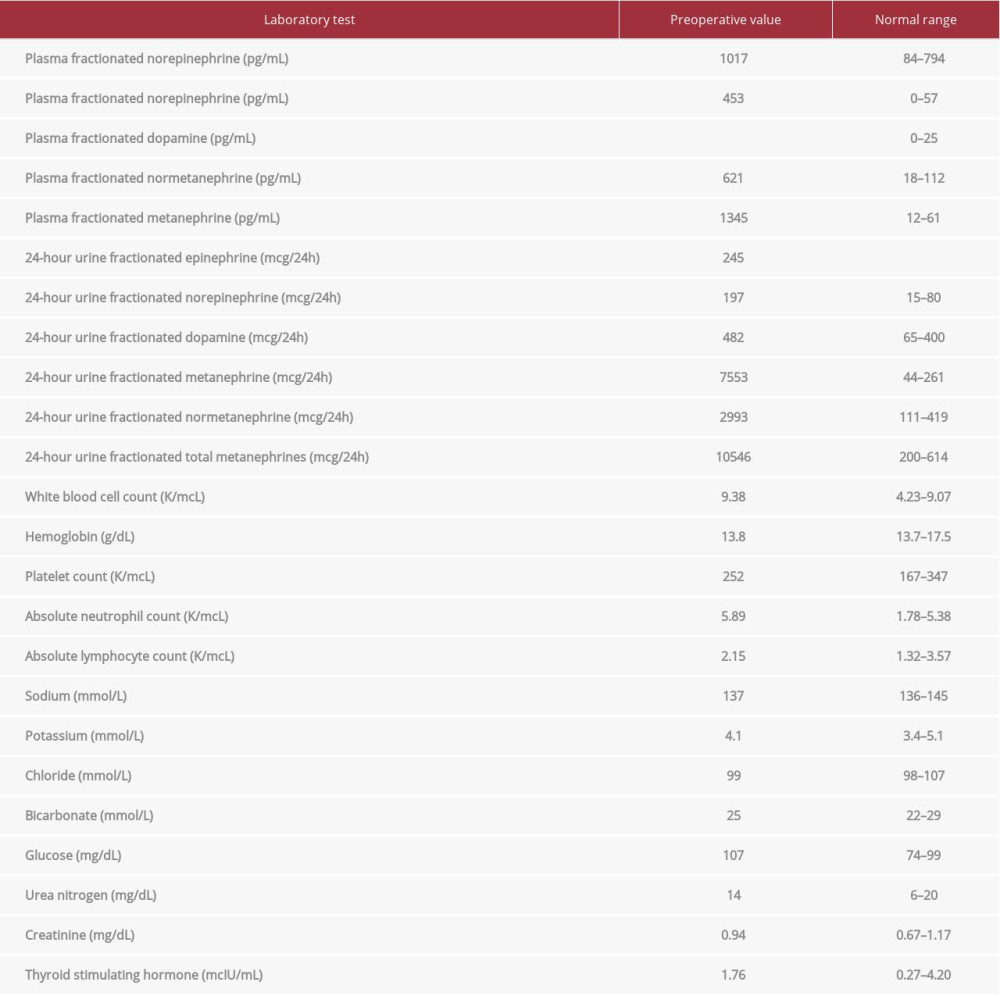

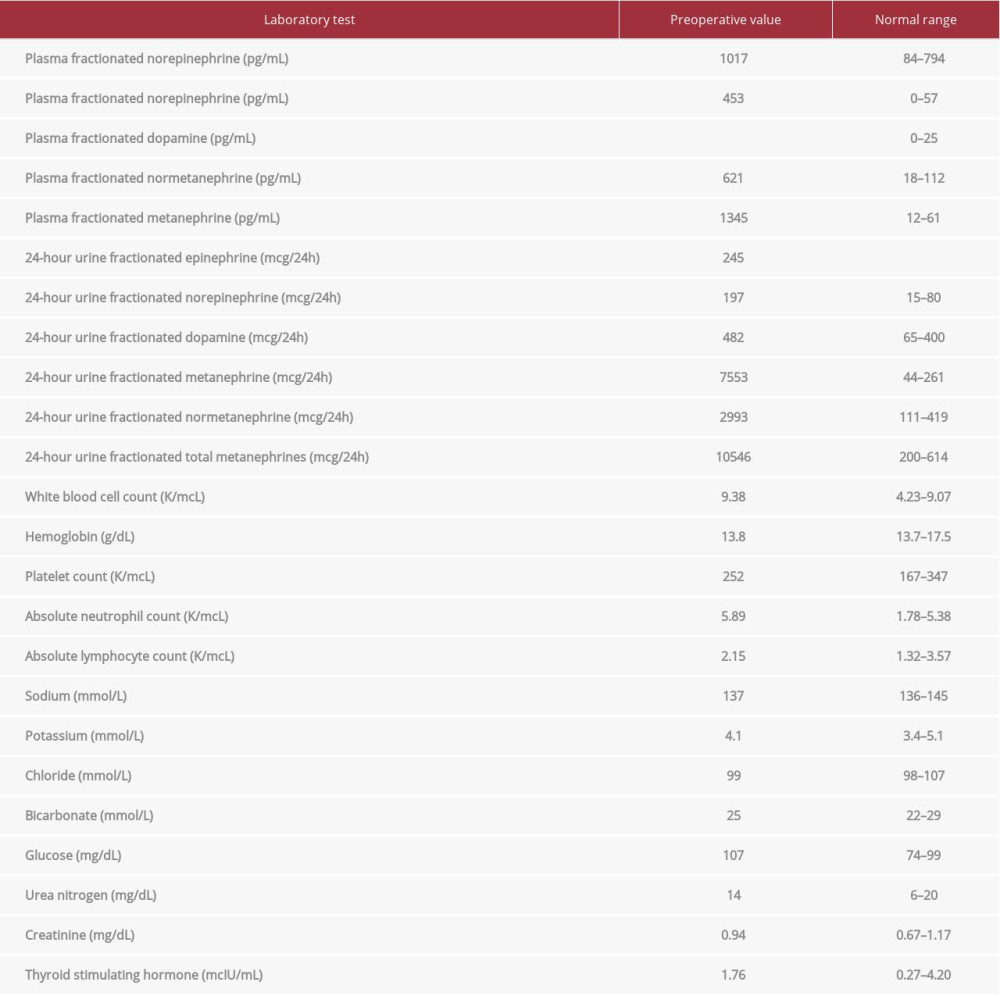

Over the next few years his symptoms persisted, but as he felt that they did not interfere significantly with his daily life, he was lost to cardiology follow-up. Six years after his original presentation, he began to experience what he described as “adrenaline attacks” characterized by palpitations, vertigo, anxiety, sweating, blurred vision, and occasional chest pain. These episodes occurred multiple times a day, lasting a few minutes each time. Several months later he developed an acute-onset right flank pain and flu-like symptoms and went to a local emergency room for evaluation. A computerized tomography scan with contrast was performed of his abdomen, which revealed the presence of a 6×5.7 cm solid mass in the right adrenal gland (Figure 1). Plasma and urinary fractionated meta-nephrines were elevated (Table 1). He was diagnosed with a pheochromocytoma and subsequently started on alpha blockade with doxazosin, followed by the addition of beta blockade with atenolol 3 months later. The patient’s symptoms initially subsided, but recurred during the following 12 months, at which point he was referred to our facility for surgical management.

During the preoperative visit, his blood pressure was 123–130/57–69 mmHg and pulse was regular at 60 bpm. His cardiac exam showed a regular heart rate and rhythm, with normal heart tones and the absence of a murmur. His abdomen was soft with normal bowel sounds and no palpable masses. The remainder of his exam was normal and non-focal. Routine complete blood count and biochemical panels were unremarkable (Table 1). An ECG was notable for the presence of diffuse delta waves (Figure 2). The patient’s estimated perioperative cardiac risk using the New Index for Preoperative Cardiovascular Evaluation was low for likelihood of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke at 30 days [6].

The patient underwent laparoscopic right adrenalectomy. Doxazosin and atenolol were administered orally on the morning of surgery and he was given midazolam intravenously just prior to induction. General anesthesia was induced with intravenous fentanyl, propofol, and rocuronium. Sevoflurane was used for maintenance of anesthesia. One intraoperative hypertensive episode occurred with a peak mean arterial pressure of 150 mmHg during manipulation of the tumor, which was managed with intravenous nitroprusside. No episodes of arrhythmia occurred during the surgery or in the immediate postoperative period. The patient was monitored in the intensive care unit for 24 h, after which he was transferred to the floor and discharged from the hospital on postoperative day 2. An electrocardiogram after surgery detailed delta waves, but for the remaining duration of the hospital stay the patient did not report any of his usual daily palpitations for the first time in 6 years. At a 1-month subsequent outpatient clinic follow-up visit, the patient remained asymptomatic, normotensive, and was off all medications.

Discussion

CLINICAL CO-MANAGEMENT OF WPW SYNDROME AND PHEOCHROMOCYTOMA:

Both WPW syndrome and biochemically active pheochromocytomas are rare conditions characterized by episodic hemodynamic instability. In WPW this is characterized by symptomatic tachyarrhythmia due to accessory pathway pre-excitation. Sympathetic stimulation is an important trigger to this type of event. In pheochromocytoma, patients can experience accelerated hypertension and tachyarrhythmia from sympathetic stimulation due to catecholamine surge from the tumor. These simultaneous presentations present a potential additive risk for both simultaneous uncontrolled supraventricular tachyarrhythmia and hypertensive crisis. Each entity has specific management considerations with respect to minimizing and managing these hemodynamic effects if they occur during the perioperative period.

In the preoperative setting, patients with pheochromocytoma are placed on an alpha-adrenergic antagonist with set blood pressure and pulse goals of 130/80 mmHg and 60–70 beats per min, respectively, to be met and maintained up through the 24 h before surgery [1,7]. Beta-adrenergic antagonists may be added for pulse control, but it is imperative that the patient be appropriately alpha-blocked first to avoid a hypertensive crisis.

In WPW, while there is no specific preoperative pharmacologic preparation, there must be a strategy in place to manage malignant arrhythmia if it occurs. In patients who develop narrow complex tachyarrhythmia (the more common orthodromic variant), adenosine or verapamil are both appropriate fast-acting and short-lasting choices for pulse management. In the case of a wide complex tachyarrhythmia, procainamide is the first-line option [2].

For a patient with both WPW and pheochromocytoma, additional multidisciplinary planning is warranted to ensure proper medication management choices are available for each possible clinical scenario, and should include strategies that can further reduce the likelihood of unintended sympathetic stimulation. These may include the preoperative use of anxiolytics and avoidance of light planes of anesthesia. Also recommended is avoidance of medications that can precipitate histamine release, and a focus on maintaining adequate preload [2,7,8].

Our patient underwent a multidisciplinary assessment by Internal Medicine, Cardiology, and Anesthesia services, and medications known to be safe in both WPW and pheochromocytoma were selected. Among these, doxazosin and atenolol were continued uninterrupted for preoperative blockade, midazolam was administered on the morning of surgery to reduce anxiety, induction was performed with fentanyl, propofol, and rocuronium, and sevoflurane was used for maintenance of anesthesia. As per usual practice at our facility during pheochromocytoma resections, nitroprusside (a potent vasodilator) and esmolol (a short-acting beta blocker) were each given briefly at the time of tumor manipulation for proactive control of blood pressure and tachycardia, respectively. Lastly, a plan was in place for adenosine or procainamide to be given in the event of WPW-related tachyarrhythmia.

Of note, during the planning period it was briefly considered that this patient should undergo an electrophysiology study in advance of surgery to risk-stratify arrhythmic events, and undergo ablation therapy if indicated [9]. However, the final consensus was that the risk of delaying his pheochromocytoma resection outweighed the benefit of an ablation therapy at this point in the clinical course.

PHEOCHROMOCYTOMA CAN EXACERBATE THE SYMPTOMS ASSOCIATED WITH THE WPW SYNDROME:

Isoproterenol, a selective β1 agonist, is used widely in electrophysiology studies to increase the sinus rate and shorten the anterograde refractory period of the accessory pathway. It is reasonable to speculate that excessive catecholamines secreted by pheochromocytomas could also increase the conduction in known accessory pathways [5] and unmask otherwise hidden ones [10–12]. Moreover, catecholamines also increase the risk of sinus tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia (SVT), atrial fibrillation (AF) and atrial flutter [13,14]. As shown by Honda et al, increased plasma norepinephrine and epinephrine concentration is associated with AF in WPW syndrome [15]. Those catecholamines secreted by a pheochromocytoma may pose an increased risk in WPW syndrome by facilitating the conduction in the accessory pathway and precipitating SVT and AF. Furthermore, pheochromocytoma also increases the risk of prolonged QTc interval and increased vagal tone in hypertensive episodes, possibly also contributing to nodal escape rhythms [14,16].

While generally thought to be rare synchronous diagnoses, interestingly, 1 of the 11 WPW syndrome patients first described by Louis Wolff, Sir John Parkinson, and Paul Dudley White in 1930 was found to have pheochromocytoma 20 years after his initial diagnosis of WPW syndrome [3]. This patient, like ours, was also reported to have become asymptomatic after resection of the pheochromocytoma. In another case, reported by Gurlek et al [5], after pheochromocytoma resection, the patient’s electrocardiogram no longer showed the WPW pattern. It is possible that in each of these cases initial symptoms attributed to WPW syndrome alone were actually due to pheochromocytoma. However, it is also possible that resection of the tumor may have had an unknown therapeutic effect on limiting conduction through the accessory pathway, beyond the resolution of a chronic hyperadrenergic state.

Conclusions

In this report we present a case of a young man with a pheochromocytoma and WPW pattern, previously misdiagnosed as an isolated WPW syndrome, who became asymptomatic through the immediate postoperative period following surgical resection of the pheochromocytoma. Pheochromocytoma patients with co-existing WPW accessory pathway have higher risk of hemodynamic complications; however, with careful perioperative planning we have demonstrated that these 2 entities can be safely managed in tandem through a perioperative course. The apparent early postoperative quiescence of palpitations in this patient is important, suggesting that his pheochromocytoma resection may have provided some degree of therapeutic management of our patient’s chronic debilitating tachyarrhythmia.

While there are few cases reported of these 2 diseases occurring in tandem, the actual incidence is unknown. It is reasonable to consider the possibility of pheochromocytoma in any patient with early-onset hypertension and episodic tachyarrhythmia, as this case illustrates. Likewise, the identification of a WPW pattern on ECG, albeit rare, is noteworthy and cannot be overlooked. These distinctions have an important impact on patient management when these 2 conditions co-exist. This includes avoiding an unintended dangerous use of unop-posed beta-adrenergic blockade in the case of an occult pheochromocytoma, as well as awareness of the risk of malignant tachyarrhythmia and sudden death associated with the presence of an accessory pathway. As in the case of our patient, the full identification of his underlying pathology, coupled with the careful crafting of a perioperative clinical strategy, resulted in the safe and successful co-management of these 2 diseases through his planned hospitalization.

Figures

References:

1.. Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M, Pacak K, Phaeochromocytoma: Lancet, 2005; 366; 665-75

2.. Bengali R, Wellens HJ, Jiang Y, Perioperative management of the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth, 2014; 5; 1375-86

3.. Hollman A, The Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: A very long follow-up: Am J Cardiol, 2014; 10; 1751-52

4.. Channappa M, Nagaraj , Bevinaguddaiah Y, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome and pheochromocytoma: Anaesthesia Case, 2013; 1; 1-4

5.. Gurlek A, Erol C, Pheochromocytoma with asymmetric septal hypertrophy and Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: Int J Cardiol, 1991; 32; 403-5

6.. Dakik HA, Chehab O, Eldirani M, A new index for pre-operative cardiovascular evaluation: J Am Coll Cardiol, 2019; 24; 3067-78

7.. Naranjo J, Dodd S, Martin YN, Perioperative management of pheochromocytoma: J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth, 2017; 4; 1427-39

8.. Peramunage D, Nikravan S, Anesthesia for endocrine emergencies: Anesthesiol Clin, 2020; 1; 149-63

9.. Page RL, Joglar JA, Caldwell MA, 2015 Acc/Aha/Hrs guideline for the management of adult patients with supraventricular tachycardia: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society: J Am Coll Cardiol, 2016; 13; e27-e115

10.. Weismuller P, Thamasett S, Grossmann G, Unmasking an exclusively retrograde accessory pathway by catecholamines: Z Kardiol, 1996; 12; 949-52

11.. Aleong RG, Singh SM, Levinson JR, Milan DJ, Catecholamine challenge unmasking high-risk features in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: Europace, 2009; 10; 1396-98

12.. Tseng ZH, Yadav AV, Scheinman MM, Catecholamine dependent accessory pathway automaticity: Pacing Clin Electrophysiol, 2004; 7; 1005-7

13.. Cismaru G, Rosu R, Muresan L, The value of adrenaline in the induction of supraventricular tachycardia in the electrophysiological laboratory: Europace, 2014; 11; 1634-38

14.. Gu YW, Poste J, Kunal M, Cardiovascular manifestations of pheochromocytoma: Cardiol Rev, 2017; 5; 215-22

15.. Honda T, Doi O, Hayasaki K, Honda T, Augmented sympathoadrenal activity during treadmill exercise in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome and atrial fibrillation: Jpn Circ J, 1996; 1; 43-49

16.. Yu R, Nissen NN, Bannykh SI, Cardiac complications as initial manifestation of pheochromocytoma: Frequency, outcome, and predictors: Endocr Pract, 2012; 4; 483-92

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Preoperative laboratory assessment, including routine screening evaluation and elevated plasma and urine fractionated metanephrines and catecholamine values.

Table 1.. Preoperative laboratory assessment, including routine screening evaluation and elevated plasma and urine fractionated metanephrines and catecholamine values. Table 1.. Preoperative laboratory assessment, including routine screening evaluation and elevated plasma and urine fractionated metanephrines and catecholamine values.

Table 1.. Preoperative laboratory assessment, including routine screening evaluation and elevated plasma and urine fractionated metanephrines and catecholamine values. In Press

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943214

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943010

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943687

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943070

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250