11 December 2023: Articles

An 85-Year-Old Man with Fever, Dyspnea, and Dry Cough Diagnosed with Idiopathic Hypereosinophilic Syndrome, Successfully Treated with High-Dose Corticosteroids

Challenging differential diagnosis, Management of emergency care, Rare disease, Educational Purpose (only if useful for a systematic review or synthesis)

Priya Goyal1CDEFG*, Shibba Takkar Chhabra1AF, Rohit Tandon1F, Bhavuk JaiswalDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.941241

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e941241

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (I-HES) is a rare disease diagnosed as absolute eosinophil count >1500 cells/µl and end-organ involvement attributable to tissue eosinophilia with no secondary cause of underlying eosinophilia. The mean age of presentation for I-HES is 44 years. The skin, lungs, and gastrointestinal (GI) system are most common sites of presenting manifestations, including fatigue, cough, dyspnea, myalgias, angioedema, rash, fever, nausea, and diarrhea. Although cardiac and neurologic symptoms are less common at presentation, they can be life-threatening.

CASE REPORT: We report the case of an 85-year-old man who presented with fever, malaise, and loss of appetite for 3 weeks, followed by dyspnea and dry cough for 2 weeks. His absolute eosinophil count was 9000 cells/µl, which was not responding to empirical antibiotic therapy, with worsening of symptoms, suggesting a non-infective origin. He was then extensively evaluated to establish underlying an etiology for specific treatment, which was negative for common causes like atypical infections, malignancy, and autoimmune disorders. He was then started on corticosteroid therapy to overcome an exaggerated immune response and reduce inflammation-related injury, to which he responded well. On follow-up, hypereosinophilia was fully cured, with reversal of end-organ involvement including myocarditis and pneumonitis.

CONCLUSIONS: This report shows that idiopathic HES can present with various clinical features and that accurate diagnosis, excluding known causes of eosinophilia, and early management are essential to prevent long-term organ damage. Our patient responded to prompt treatment with high-dose corticosteroids.

Keywords: Geriatrics, myocarditis, Multimodal Imaging, Hypereosinophilic Syndrome, Pulmonary Eosinophilia

Background

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a rare disorder characterized by elevated levels of eosinophils in the blood or tissues, resulting in organ damage and/or dysfunction. The diagnosis of HES is based on the criteria established by the International Cooperative Working Group on Eosinophil Disorders (2011) characterized by blood eosinophilia >1500 eosinophils/μL on 2 examinations (≥1 month apart, except for life-threatening organ damage when diagnosis can be made immediately) and/ or tissue eosinophilia; organ damage and/or dysfunction attributable to tissue eosinophilia; and exclusion of other disorders or conditions as the major reason for organ damage [1].

Patients with HES can present with a variety of concerns like fatigue, cough, dyspnea, myalgias, angioedema, rash, fever, retinal lesions, nausea, and diarrhea, but some patients have no symptoms at all [2]. Skin, lung, and gastrointestinal manifestations are most common at presentation, while cardiac and neurological problems are less frequent but are associated with higher mortality rates [3]. The 2016 WHO classification system categorizes HES into different subtypes based on molecular characteristics after ruling out other potential causes of eosinophilia. These include: 1) myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with eosinophilia and PDGFRA, PDGFRB or FGFR1 rearrangement or with PCM1-JAK2 (the latter still representing a provisional entity); 2) myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) subtype: chronic eosinophilic leukemia, not otherwise specified (CEL, NOS); and 3) idiopathic HES, which is a diagnosis of exclusion [4].

Delayed treatment can result in severe eosinophil mediated end-organ dysfunction particularly in elderly patients attributed to their comorbidities, low organ reserve, and atypical presentations leading to delayed diagnosis. The diagnosis of HES requires extensive diagnostic workup, making timely identification and early initiation of treatment challenging. Further, the lack of standardized treatment guidelines and limited therapeutic options pose challenges in managing this rare and unpredictable condition. The first-line treatment for idiopathic HES has traditionally been corticosteroids. This choice may arise due to the potentially harmful adverse effects of other available second-line agent such as hydroxyurea, cyclosporine, and alpha interferon. Although safer biological agents like mepolizumab have been approved, its efficacy as a first-line treatment has not yet been studied in comparison to corticosteroids [5].

This case report on a geriatric patient with idiopathic HES highlights considering I-HES as a differential diagnosis in geriatric patients presenting with end-organ manifestations (cardiac and respiratory involvement in this case), along with peripheral blood eosinophilia with no clear underlying etiology, and the importance of early treatment with high-dose corticosteroids in life-threatening situations for improved outcomes. Furthermore, we hope to stimulate further research to explore the etiology and thus potential targets for treatments.

Case Report

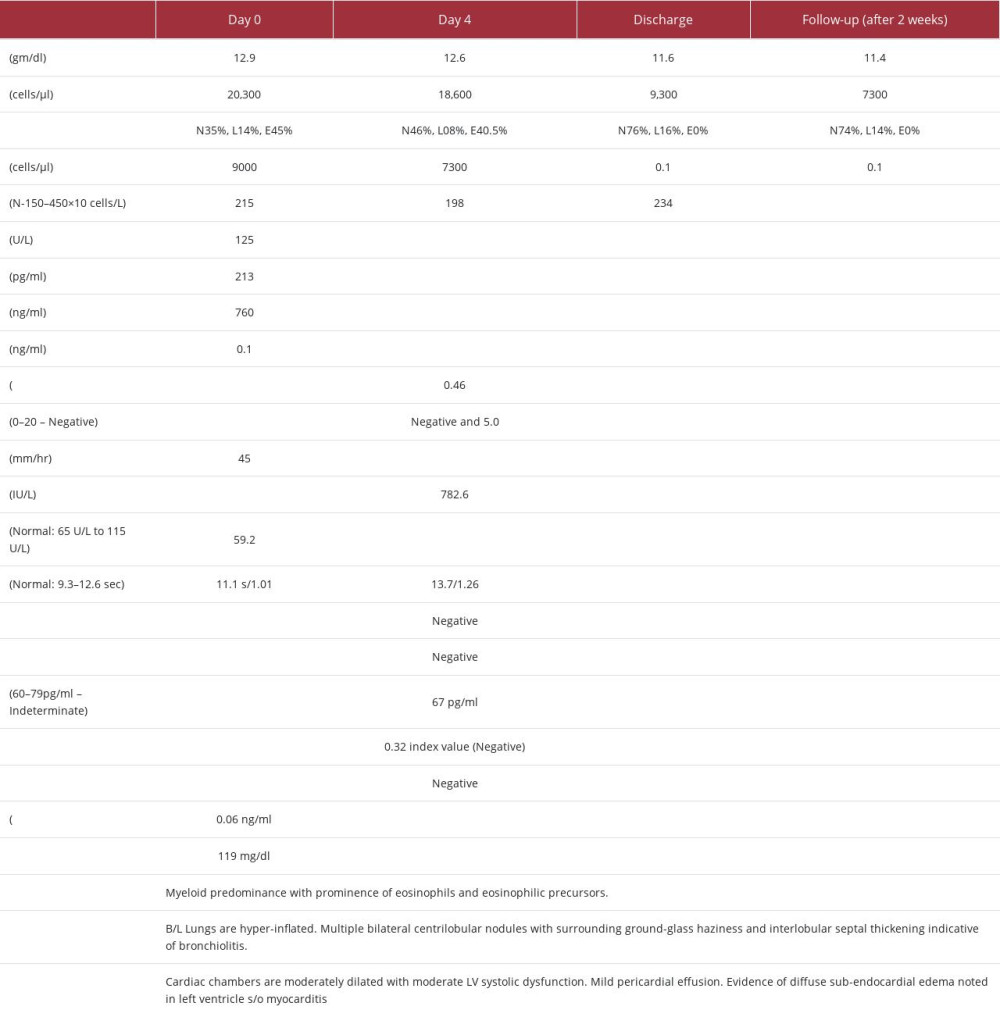

An 85-year-old male patient presented with chief concerns of fever, severe malaise, and loss of appetite for 3 weeks, followed by dyspnea and dry cough for 2 weeks. He had no history of chest pain, palpitations, rash, pain abdomen, or jaundice and no prior history of asthma, atopy, recent travel, or significant animal or bird exposure. He was febrile, coherent, and undernourished with heart rate 122 bpm, blood pressure 110/70 mmHg, axillary temperature 38.4°C, SpO2 91%, and no palpable lymph nodes. Chest examination revealed bilateral infra-scapular crepitation with bilateral rhonchi. On the day of admission, a complete blood count was suggestive of leukocytosis with eosinophilic predominance and a high absolute eosinophil count (AEC) of 9000 cells/ul (see the investigation profile table). Routine tests such as viral markers for HBV, HCV, LFT, RFT, and routine urine tests were inconclusive. Stool for occult blood was also negative. Antibody titers (ANA and ANCA) to rule out hypersensitivity and autoimmune etiology were negative. CT chest showed hyper-inflated lungs, pericardial effusion, centrilobular nodules with ground-glass haze, interlobular septal thickening, with no signs of lung fibrosis or malignancy likely suggestive of bronchiolitis (Figure 1). ECG showed sinus tachycardia. Trop-t and CK-MB levels were mildly raised. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE2D) showed global hypokinesia of the left ventricle with a reduced ejection fraction of 36–38%. Results of coronary angiography were normal. He was initially managed with beta-lactam antibiotic in view of an infective etiology for myocarditis and pneumonitis plus low-dose loop diuretics, antipyretics, and diethylcarbamazine (DEC) 100 mg BD for 21 days for tropical pulmonary eosinophilia. On hospital day 4, he had persistent intermittent fever, with a similar peripheral blood picture. Further investigations for atypical pneumonia were negative (Table 1). Fungal marker (1,3 beta D glucan) was indeterminate, but an empirical anti-fungal antibiotic was started. Bone marrow aspiration to rule out malignancy was done, which was suggestive of hypercellular marrow exhibiting prominence of eosinophils and eosinophilic precursors (Figure 2). Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging showed evidence of diffuse subendocardial edema and moderate left ventricular dysfunction (Figures 3, 4), conclusive for myocarditis. He was started on IV hydrocortisone 100 mg every 8 h, to which he responded well symptomatically. His total leukocyte count (TLC) was normal, with AEC of 0.1 cells/µl, Spo2 98% after the 4th day of therapy. After a complete week of treatment, hydrocortisone was tapered every 12 h to 50 mg on 1 day and then switched to methylprednisolone at a dose of 24 mg for 4 days, followed by 16 mg on the day of discharge. In the following week, his left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) increased from 36% to 44%. He remained asymptomatic, he had normal vesicular breath chest sounds, spo2 was 98%, BP was 110/70 mmHg, heart rate was 60 bpm, and respiratory rate (RR) was 20 breaths/min. He was discharged on ACE inhibitor, DEC, and methylprednisolone 16 mg, which was tapered over 4 weeks.

Discussion

The management of HES is centered around investigating for an underlying cause while preventing any eosinophil-related end-organ damage. In our case, a comprehensive medical history was taken for the patient’s primary concerns of fever, malaise, loss of appetite, cough, and difficulty breathing. A coronary angiography was conducted to exclude the possibility of ischemic heart disease, which was negative. Further investigations were carried out to eliminate the possibility of hyper-eosinophilia due to various factors such as allergies, drug hyper-sensitivity, and autoimmune conditions (ANA and ANCA titers), all of which yielded negative results (Table 1). To address the suspicion of an infectious cause based on abnormal HRCT and TTE findings, antibiotics were initiated. Considering the endemicity of tropical pulmonary eosinophilia, he was started on diethylcarbamazine for 21 days. However, even after 4 days of treatment, the high eosinophil count persisted. Therefore, bone marrow aspiration was performed to rule out malignancy, which revealed a predominance of myeloid cells with no indications of malignancy. No immunohistochemical analysis was performed specifically to detect malignancy. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging was performed due to the persistent abnormal blood picture and TTE findings, which showed enhancement of subendocardial region along anterolateral segments of the LV on T2 imaging and global hypokinesia of the LV. A diagnosis of eosinophilic myocarditis (EM) was then made upon considering hypereosinophilic blood profile and abnormal TEE findings with no other secondary cause for myocarditis present. Although endomyocardial biopsy is the criterion standard for diagnosis of EM, CMR is valuable tool for early detection of the disease and prompt initiation of appropriate therapy when cardiac biopsy is impractical and not safe for the patient [6]. Also, the sensitivity of biopsy is approximately 54%, which is limited by patchy involvement of the myocardium and inadequate sample size [7].

This case is unique due to our approach to diagnosis to finally establish an idiopathic etiology, age of presentation, and rationale of management with corticosteroids, which in our experience can be started safely and earlier in the disease course after excluding other etiologies. The idiopathic form of HES is the most common, constituting about 45% of cases, followed by lymphocytic HES (L-HES) around 19%, and myeloid HES (M-HES) around 12%, according to a case series. The mean age of presentation for I-HES is 44 years, which contrasts with the age of our patient, which highlights the consideration of HES in differential diagnosis in the geriatric age group. In I-HES, the most commonly affected organs are bone marrow (34.9%), heart (34.9%), and lungs (33.6%), which is similar to the organs affected in our patient. While in patients with M-HES, the most common organs affected are the spleen (64.5%) bone marrow (36.4%), heart, and liver (both 29.8%). L-HES is characterized by involvement of the skin (79.0%), bone marrow (41.9%), and lymph nodes (33.9%). This molecular classification of HES is important as it guides targeted treatment approaches for the various etiologies behind the subtypes. Cardiac symptoms in HES are infrequent, with less than 5% of patients initially showing them. However, studies suggest a higher prevalence, possibly due to publication bias favoring severe cases [8]. Nevertheless, cardiovascular complications associated with HES are known to have a poor prognosis and can result in fatal outcomes like myocardial necrosis and thromboembolic complications resulting within 1 month of symptom onset [9]. Other factors reported to be predictive of worse outcomes in HES are male sex, higher degree of eosinophilia, lack of response to corticosteroids, and association with a myeloproliferative syndrome [10]. Identifying HES early is crucial for achieving better outcomes in such cases, as it allows for the transition of second-line agents in cases that are non-responsive to steroids in a safer timeframe.

High-dose corticosteroids should be initiated promptly in these cases. According to a case series, the dosages used in various instances vary widely based on clinical severity, with a median maximal dose of 40 mg (range 5–625 mg) and the median maintenance dose 10 mg (range 1–40 mg daily). The duration ranged from 2 months to 20 years [11]. It is crucial to perform appropriate diagnostic studies before initiating corticosteroid therapy, but treatment should not be delayed in the face of worsening signs and symptoms. Some studies also recommend adding ivermectin to prevent corticosteroid-associated hyperinfection [12]. Thus, medication choices should be based on the patient’s geographic location, medical condition, and immune status. If there is no improvement in the eosinophil count and symptoms after 24–48 h of high-dose corticosteroid therapy, a second agent should be added such as imatinib, immunomodulatory agents (interferon alpha, cyclosporin or azathioprine), myelosuppressive therapy (hydroxycarbamide), or monoclonal anti-interleukin 5 antibody (mepolizumab) [13,14]. The recently approved drug mepolizumab anti-IL-5 antibody has shown efficacy in HES, but lack of data on efficacy over corticosteroids and higher costs must be considered before using it as first-line therapy for HES [15]. In our case, the patient showed an improvement in symptoms, normalization of eosinophil counts, and LVEF improved from 36% to 44% after receiving high-dose corticosteroid treatment. Further chest imaging to monitor the progress of eosinophilic pneumonia was not conducted. The patient remained asymptomatic, his chest had normal vesicular breath sounds, spo2 was 98%, BP was 110/70 mmHg, heart rate was 60 bpm, and his RR was 20 breaths/min on discharge. There is currently no consensus on the best approach to managing HES, and different medical institutions may have varying practices in this regard. Further research is needed to identify the underlying mechanisms of HES to delineate called idiopathic cases and provide targeted treatment options. The follow-up period for our patient was short but patients with HES require long-term follow-up due to the possibility of ANCA-negative eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis as the underlying pathogenesis, and 5% of all HE cases eventually converting into hematological malignancy [16,17].

Conclusions

This report highlights that idiopathic HES can present with various clinical features and that accurate diagnosis, excluding known causes of eosinophilia, and early management are essential to prevent long-term organ damage. Our patient responded to prompt treatment with high-dose corticosteroids.

Figures

References:

1.. Valent P, Klion AD, Horny HP, Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes: J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2012; 130(3); 607-12.e9

2.. Weller PF, Bubley GJ, The idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome: Blood, 1994; 83(10); 2759-79

3.. Rhyou HI, Lee SE, Kim MY, Idiopathic hypereosinophilia: A multicenter retrospective analysis: J Asthma Allergy, 2022; 15; 1763-71

4.. Shomali W, Gotlib J, World Health Organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2019 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management: Am J Hematol, 2019; 94(10); 1149-67

5.. Klion A, Hypereosinophilic syndrome: Approach to treatment in the era of precision medicine: Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program, 2018; 2018(1); 326-31

6.. Looi JL, Ruygrok P, Royle G, Acute eosinophilic endomyocarditis: Early diagnosis and localisation of the lesion by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: Int J Cardiovasc Imaging, 2010; 26(Suppl. 1); 151-54

7.. Sasano H, Virmani R, Patterson RH, Robinowitz M, Guccion JG, Eosinophilic products lead to myocardial damage: Hum Pathol, 1989; 20(9); 850-57

8.. Requena G, van den Bosch J, Akuthota P, Clinical profile and treatment in hypereosinophilic syndrome variants: A pragmatic review: J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2022; 10(8); 2125-34

9.. Podjasek JC, Butterfield JH, Mortality in hypereosinophilic syndrome: 19 years of experience at Mayo Clinic with a review of the literature: Leuk Res, 2013; 37(4); 392-95

10.. Leru PM, Eosinophilic disorders: Evaluation of current classification and diagnostic criteria, proposal of a practical diagnostic algorithm: Clin Transl Allergy, 2019; 9; 36

11.. Ogbogu PU, Bochner BS, Butterfield JH, Hypereosinophilic syndrome: A multicenter, retrospective analysis of clinical characteristics and response to therapy: J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2009; 124(6); 1319-25.e3

12.. Mejia R, Nutman TB: Curr Opin Infect Dis, 2012; 25(4); 458-63

13.. Klion AD, How I treat hypereosinophilic syndromes: Blood, 2015; 126(9); 1069-77

14.. Butt NM, Lambert J, Ali S, Guideline for the investigation and management of eosinophilia: Br J Haematol, 2017; 176(4); 553-72

15.. Gleich GJ, Roufosse F, Chupp G, Safety and efficacy of mepolizumab in hypereosinophilic syndrome: An open-label extension study: J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2021; 9(12); 4431-40 e1

16.. Khoury P, Akuthota P, Kwon N, HES and EGPA: Two sides of the same coin: Mayo Clin Proc, 2023; 98(7); 1054-70

17.. Jin JJ, Butterfield JH, Weiler CR, Hematologic malignancies identified in patients with hypereosinophilia and hypereosinophilic syndromes: J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2015; 3(6); 920-25

Figures

In Press

21 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942921

22 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943346

24 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943560

26 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943893

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250