14 October 2020: Articles

Clinical Characteristics of 3 Patients Infected withCOVID-19: Age, Interleukin 6 (IL-6), Lymphopenia, and Variations in Chest Computed Tomography (CT)

Unknown etiology

Jing Huang1A, Jie Li2E, Zhenwei Zou1A, Asha Kandathil3D, Jun Liu1BC, Shaohong Qiu4AD, Orhan K. Oz3CEF*DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.924905

Am J Case Rep 2020; 21:e924905

Abstract

BACKGROUND: COVID-19 has been identified as the cause of the large outbreak of pneumonia in patients in Wuhan with shared history of exposure to the Huanan seafood market; however, there is more to learn about this disease. Some experts report that the virus may have reduced toxicity during transmission, but others say that toxicity does not change during transmission.

CASE REPORT: In this case series, we report clinical and imaging characteristics of 3 patients (A, B, and C) infected with COVID-19. In an exposure-tracking epidemiological investigation, we found that it is possible that Patient A transmitted the infection to her treating physician, Patient B. Patient B then likely transmitted the infection to her family member, Patient C. From the chest CT studies and clinical characteristics, we postulate that the virulence did not decrease during human-to-human transmission. In previous studies, patients with the virus infection had changes in chest CT; however, we found that during the early stages of this disease, some patients (Patient C) may have normal chest CT scans and laboratory studies. Most importantly, we found that IL-6 levels were highest and lymphocyte count was lowest in those with more severe infection.

CONCLUSIONS: In this case series, we report the exposure relationship of the 3 patients and found that chest CT scans may not have any changes at the beginning of this disease. Lymphopenia and elevated levels of IL-6 can be found after infection.

Keywords: Body Image, COVID-19, Disease Transmission, Infectious, Receptors, Interleukin-6, Betacoronavirus, COVID-19, Comorbidity, Coronavirus Infections, Interleukin-6, Lymphopenia, Pandemics, Pneumonia, Viral, Radiography, Thoracic, SARS-CoV-2, Tomography, X-Ray Computed

Background

Recently, COVID-19, a corona virus pneumonia outbreak which began in Wuhan Hubei province in China, has rapidly become a global health issue all over the world [1–3]. COVID-19 is estimated to have resulted in 4 483 864 cases in 185 countries with 303 825 deaths as of May 15, 2020. Many countries chose to lock down or order “stay at home” to prevent virus rapid transmission and protect people [4–6]. Some researchers report that the virus may have reduced toxicity during transmission or even suddenly disappear when the temperature rises; however, other researchers insist that COVID-19 toxicity does not change during transmission [7–9].

From the current experience with COVID-19, death has more often been seen among the older people (age >60 years). Those with pre-existing conditions or diseases are more susceptible to the new virus and their condition can suddenly and rapidly progress from an asymptomatic infection, including slight fever, cough, or diarrhea, to severe pneumonia, respiratory failure, and multiple organ failure, sometimes leading to death [2,10]. The progression is closely related to an “inflammatory storm” involving a number of different cytokines. Laboratory analysis shows these patients tend to have lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and increased or even normal C-reactive protein (CRP), lactate dehydrogenase, and interleukin levels [11]. The main CT findings of COVID-19 are ground-glass opacities (GGOs) and patchy consolidations, which are also the main indicators of disease initiation and progression [12]. However, not all patients follow the same pattern, and there are patients who are symptomatic and have positive nucleic acid test results but have normal CT scan or laboratory tests, which may be negative or low during treatment. In the present case series, we report the clinical characteristics, radiological findings, treatment, and outcome of 3 patients with COVID-19, illustrating the range of severity and outcomes.

Case Reports

SEVERE COVID-19 INFECTION: PATIENT A:

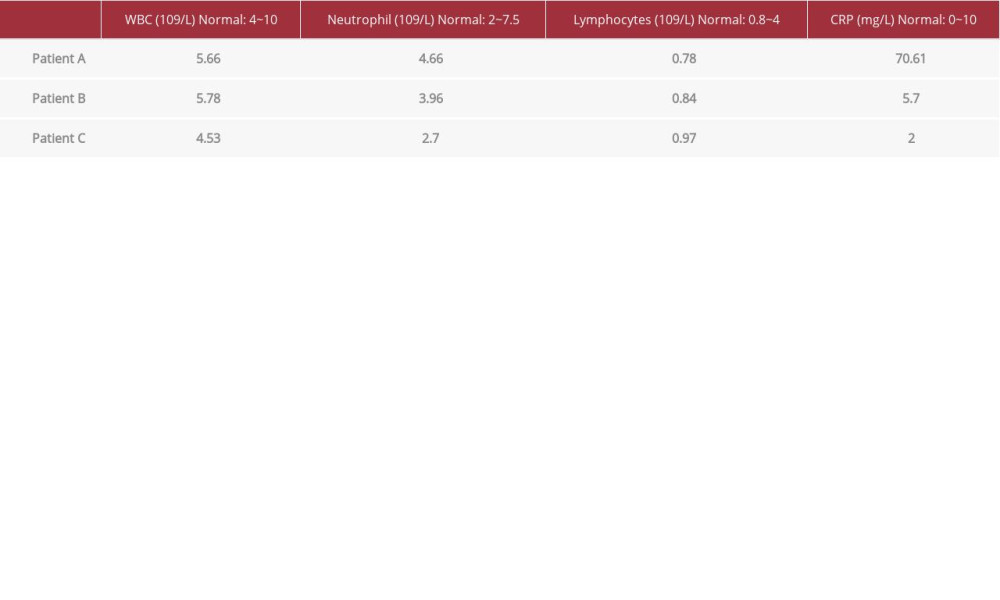

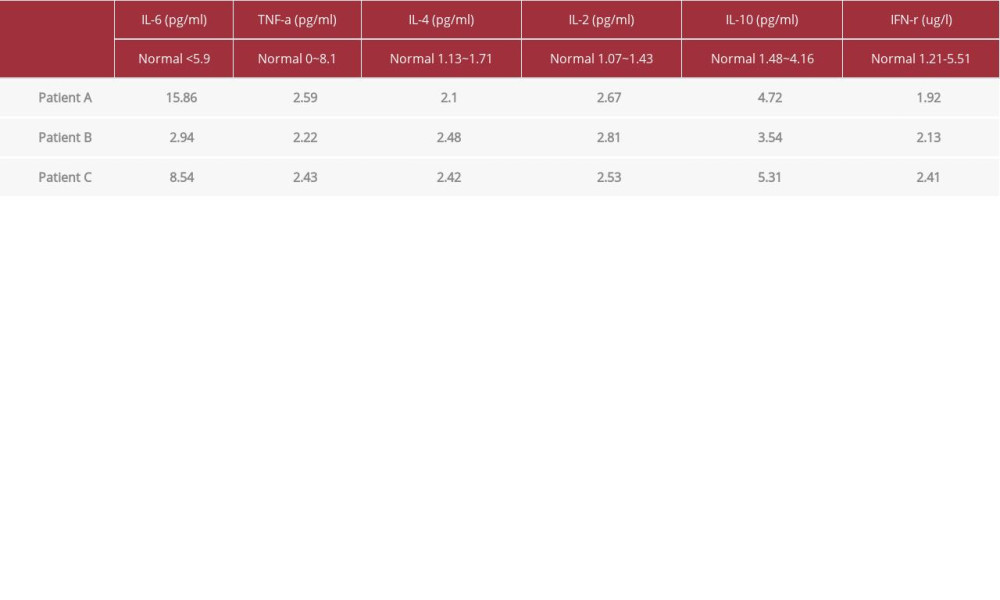

A 69-year-old woman presented with headache, vomiting, low-grade fever, and a maximum body temperature of 37.5°C on January 9, 2020. She did not appear to have other diseases and never smoked. Her symptoms did not improve much after taking over-the-counter cold medicine and amoxicillin. She had dizziness, vomiting, cough, chest tightness, muscle soreness, and other discomforts, and her body temperature gradually increased to 38.5°C. Her initial chest CT was normal (not shown). She was unsuccessfully treated with moxifloxacin at a local hospital in Wuhan on January 12, 2020 and then came to our outpatient facility on January 14, 2020. A chest CT showed multiple, peripheral ground-glass opacities in both lungs suggestive of viral pneumonia (Figure 1A). Tests for influenza A and influenza B viruses were negative. Laboratory tests revealed CRP: 70.61 mg/L and lymphocyte: 0.78×109/L (Table 1). Cytokine detection in blood revealed IL-6: 15.86 pg/ml (Table 2). The nucleic acid test for COVID-19 was positive on January 15, 2020. A throat swab was used to collect samples to extract COVID-19 RNA from patients suspected of having COVID-19 infection. We used a respiratory sample RNA isolation kit (Zhongzhi, Wuhan, China) and this suspension was used for real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis by using a COVID-19 nucleic acid detection kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Shanghai Bio-Reproductive Medicine Technology Co., Ltd.). These diagnostic criteria are based on the recommendations of the National Institutes for Disease Control and Prevention (http://ivdc.chinacdc.cn/kyjz/202001/t20200121_211337.html). The Ct value is defined as a medium load from 37 to less than 40 and needs to be confirmed by retesting. After treatment with moxifloxacin, vancomycin, and oseltamivir on January 16, 2020, blood oxygen decreased to SPO2=92%. Subsequently, after January 16, 2020, she was given linezolid, voriconazole, and moxifloxacin, oseltamivir, and gamma globulin, with no improvement. She died on January 22, 2020, 13 days after the onset of fever.

NON-SEVERE COVID-19 INFECTION: PATIENT B:

A 38-year-old woman began to have chest tightness on January 19, 2020. She started to have fever on January 22, 2020, with body aches, dry cough, and a body temperature of up to 37.4°C. Her temperature normalized after physical cooling. Prior to this, she was in good health and does not smoke. The nucleic acid test for COVID-19 was positive on January 23 using the same methods as described above, and the diagnosis of 2019-nCoV infection was confirmed. On January 24, 2020, she was admitted to the hospital for treatment. Routine blood tests showed lymphocytes: 0.84×109/L (Table 1). Cytokine detection in blood revealed an IL-6=2.94pg/ml (Table 2). Tests for influenza A and influenza B viruses were negative. A chest CT on day 5 showed a few small left lower-lobe opacities (Figure 1B). On January 24, 2020, she was started on moxifloxacin, oseltamivir, and gamma globulin and was placed in isolation. At present, the patient has recovered and is in good stable general health.

NON-SEVERE COVID-19 INFECTION: PATIENT C:

A 37-year-old man developed fatigue on January 27, 2020, and then developed fever up to 37.6°C. He was in good health before and never smoked. On January 28, 2020, the nucleic acid test for COVID-19 was positive but the chest CT scan was normal (Figure 2). Routine blood tests showed lymphocyte= 0.97×109/L (Table 1). Cytokine detection in blood revealed IL-6=8.54 pg/ml (Table 2). Later, he was admitted to the hospital for isolation and observation. After treatment with moxifloxacin, oseltamivir, and gamma globulin, his body temperature was normal on January 30, 2020, but a chest CT on day 5 showed multiple small ground-glass opacities in both lungs (Figure 1C). At present, he has recovered and is in good stable general health.

Comparing the 3 cases, we found older age and higher inflammatory status with increasing cytokines such as IL-6 or CRP are associated with poor outcome. Lymphopenia is a common finding. While the association with inflammation and the elevated IL-6 levels have been reported, our patients became ill early in the pandemic and were presenting these findings. These cases show that patients can have slight symptoms and normal chest CT in the early phases of the disease. Non-severe patients may have normal or small opacities on their chest CT. The presence of peripheral ground-glass opacities with bilateral distribution, multi-lobar and posterior involvement, and subsegmental vessel enlargement appear to be common characteristics of those with severe COVID-19 pneumonia [13,14].

Discussion

Patient A became symptomatic on January 9, 2020 and was treated by Patient B, who is an infectious disease physician, beginning January 14, 2020. Patient B became symptomatic with fever 8 days later on January 22, 2020 and did not have contact with any other patients with COVID-19 infection. Patient B performed a tracheotomy on patient A on January 17, 2020. Therefore, we speculate that patient B was very likely to have been infected by patient A. Patient C, who is patient B’s husband, became symptomatic on the 4th day after patient B was confirmed to be infected. In the week before he became infected, he did not have contact with other people outside his home, so we speculate that patient C was infected by patient B.

From the perspective of the clinical symptoms of these 3 patients, we found that the clinical symptoms of patient A were the most severe. The symptoms of Patient B and Patient C were almost the same. The disease progression of Patient A was the fastest, with only 13 days from fever to death. The patient’s blood oxygen decreased on the 9th day, and there was no significant improvement with administration of large amounts of oxygen. The rapid disease progression in Patient A may be related to the older age (69 years old). For patient A, after having cold-like symptoms, she took cold medicine and amoxicillin for 1 week from January 9 to January 15. On January 16, 2020 she was given moxifloxacin, vancomycin, and oseltamivir treatment, but the blood oxygen still decreased. Therefore, after January 16, 2020, the doctor modified the treatment by using linezolid, voriconazole, and moxifloxacin, oseltamivir, and gamma globulin. However, none of these treatments improved the patients’ condition. Patient A took several antibacterial drugs because she had an infection and had fever and increased CRP (70.61 mg/L). All medications were used strictly according to instructions; therefore, the risk of medication adverse effects seems low. The death of Patient A may also be closely related with high inflammation status (IL-6: 15.86 pg/ml, CRP 70.61mg/L). In addition, patient A may have missed the best treatment window due to delayed viral nucleic acid detection and normal chest CT when she first presented, both of which are easily ignored by doctors in clinical practice. Additionally, for treatment, ECMO is a very limited resource in this hospital. Therefore, patient A did not have a chance to receive it before she died. Patient B did not show a decrease in blood oxygen, the fever was controlled, and fatigue improved. Patient C was likely infected by Patient B, but had slightly worse symptoms than Patient B. Moreover, the time from infection to the time of presentation to physicians for both patient A and B infected was estimated in the range from 1 to 14 days (most likely 3–10 days). Given the short time between infections, it is likely the virulence of the virus did not change during transmission, although gene sequencing of the virus may be a better option to explain the viral pathogenicity and transmissibility. Age may have had some protective effect for patient B. Some studies have shown that men tend to have higher risk for infection and more severe symptoms compared with women [15–20]. However, related studies have been hampered by a large heterogeneity in testing and reporting of the data. Based on clinical practice, it seems men have higher death rates compared to women. However, the data is confusing when taking the health condition, comorbidities, and hormone levels into consideration. The proportion of positive tests is almost equal in men and women, which indicates they still have a similar risk of infection with COVID-19 [8,21].

None of these 3 patients received hydroxychloroquine and/or azithromycin treatment since that the drug scheme was not available at the time they were admitted to clinics in January 2020 [22–24].

Chest CT findings were variable in our case series, but in general the findings were worse with increasing severity of infection. Figure 1 shows chest CT images on day 5 of illness for all 3 patients. The CT findings for patient A are the most extensive (Figure 1A), with a large area of inflammatory changes in both lungs. The patient died from respiratory failure 8 days later. Chest CT in Patient B shows only a few ground-glass changes in the left lower lung (Figure 1B). The initial chest CT scan in Patient C showed no abnormalities in the early stages of the disease (Figure 2). After 1 week, there were some lower-lobe opacities (Figure 1C). Figure 3 shows the disease course in the 3 patients. During the follow-up of patients B and C, chest CT scan results for Patient B (March 12th) and Patient C (February 27th) returned to normal, with no previous CT changes (Figure 4).

The laboratory results show that the WBC count and neutrophil count were normal in all 3 patients; however, the lymphocytes were reduced (Table 1). The cytokine test results showed that IL-6 was significantly increased (Table 2). Cytokines reflect the degree of inflammation of the lungs and indicate that Patient A had severe inflammation. The degree of increase in IL-6 can be used as a laboratory test indicator for the degree of infection and inflammatory changes associated with COVID-19 infection. From chest CT screen and laboratory findings, we believe the severity of COVID-19 infection can be inferred at the initial presentation to the healthcare system.

Conclusions

Our analysis of these 3 cases did not show that the virus lost virulence during transmission. Further gene sequencing of the virus is urgently needed to definitively correlate virulence with severity of infection [25,26]. In addition, patients infected with the virus may not have changes on chest CT in the early stages of disease, which is easily ignored by doctors in clinical practice. Thus, early testing of CVID-19 nucleic acid and other cytokine levels would be better options to find infected people. Among cytokine tests, IL-6 seems to be sensitive detector since it can change during the disease initiation. Moreover, IL-6 can reflect the degree of infection and inflammatory changes associated with COVID-19. Indeed, a review of clinical trials related to COVID-19 at clinical trials.gov shows 2 studies are targeting IL-6 signaling through targeting the IL-6 receptor with Sarilumab. In summary, older age, a high inflammatory status (cytokine level increased), lymphopenia, and bilateral multi-lobar opacities on chest CT are closely associated with higher severity and mortality from COVID-19 infection in our series. Other comorbidities, especially lung and cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, increase the risk of death from COVID-19 infection, although it appears our 3 patients did not have these.

Figures

References:

1.. Chan JF-W, Yuan S, Kok K-H, A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster: Lancet, 2020; 395(10223); 514-23

2.. Chen H, Ai L, Lu H, Li H, Clinical and imaging features of COVID-19: Radiol Infect Dis, 2020; 7(2); 43-50

3.. Singh AG, Chaturvedi P, Clinical trials during COVID-19: Head Neck, 2020; 42(7); 1516-18

4.. Hong Y-R, Lawrence J, Williams D, Iii AM, Population-level interest and tele-health capacity of US hospitals in response to COVID-19: Cross-sectional analysis of Google Search and National Hospital Survey Data: JMIR Public Heal Surveill, 2020; 6(2); e18961

5.. , Safeguard research in the time of COVID-19: Nat Med, 2020; 26(4); 443

6.. Chinazzi M, Davis JT, Ajelli M, The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: Science, 2020; 368(6489); 395-400

7.. Thevarajan I, Nguyen THO, Koutsakos M, Breadth of concomitant immune responses prior to patient recovery: A case report of non-severe COVID-19: Nat Med, 2020; 26(4); 453-55

8.. Xu Y, Li X, Zhu B, Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding: Nat Med, 2020; 26(4); 502-5

9.. Retsas S, Clinical trials and the COVID-19 pandemic: Hell J Nucl Med, 2020; 23(1); 4-5

10.. Wu JT, Leung K, Bushman M, Estimating clinical severity of COVID-19 from the transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China: Nat Med, 2020; 26(4); 506-10

11.. Yuan J, Zou R, Zeng L, The correlation between viral clearance and biochemical outcomes of 94 COVID-19 infected discharged patients: Inflamm Res, 2020; 69(6); 599-606

12.. Pan F, Ye T, Sun P, Time course of lung changes on chest CT during recovery from 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia: Radiology, 2020; 295(3); 715-21

13.. Jiang Y, Guo D, Li C, Chen T, Li R, High-resolution CT features of the COVID-19 infection in Nanchong City: Initial and follow-up changes among different clinical types: Radiol Infect Dis, 2020; 7(2); 71-77

14.. Duarte-Neto AN, de Almeida Monteiro RA, Ferraz da Silva LF, Pulmonary and systemic involvement of COVID-19 assessed by ultrasound-guided minimally invasive autopsy: Histopathology, 2020 [Online ahead of print]

15.. Serge R, Vandromme J, Charlotte M, Are we equal in adversity? Does Covid-19 affect women and men differently?: Maturitas, 2020; 138; 62-68

16.. Li L-Q, Huang T, Wang Y-Q, 2019 novel coronavirus patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate and fatality rate of meta-analysis: J Med Virol, 2020; 92(6); 577-83

17.. Shrestha A, Bajracharya S, Clinical characteristics of suspected COVID-19 admitted to the isolation ward of Patan Hospital, Nepal: J Patan Acad Heal Sci, 2020; 7(1); 7-12

18.. Jin J-M, Bai P, He W, Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: Focus on severity and mortality: Frontiers Public Health, 2020; 8; 152

19.. O’Connor K, Survey reveals gender gap in COVID-19 stress: Psychiatric News, 2020; 55(10); 2020.5b3

20.. Wang D, Yin Y, Hu C, Clinical course and outcome of 107 patients infected with the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, discharged from two hospitals in Wuhan, China: Crit Care, 2020; 24(1); 188

21.. Venkatakrishnan K, Yalkinoglu O, Dong JQ, Benincosa LJ, Challenges in drug development posed by the COVID-19 pandemic: An opportunity for clinical pharmacology: Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2020 [Online ahead of print]

22.. Rosenberg ES, Dufort EM, Udo T, Association of treatment with hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin with in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 in New York State: JAMA, 2020; 324(1); 2493-502

23.. Mercuro NJ, Yen CF, Shim DJ, Risk of QT interval prolongation associated with use of hydroxychloroquine with or without concomitant azithromycin among hospitalized patients testing positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): JAMA Cardiol, 2020 [Online ahead of print]

24.. Sarayani A, Cicali B, Henriksen CH, Brown JD, Safety signals for QT prolongation or Torsades de Pointes associated with azithromycin with or without chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine: Res Soc Adm Pharm; 2020 [Online ahead of print]

25.. Wang D, One-pot detection of COVID-19 with real-time reverse-transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) assay and Visual RT-LAMP assay: Biorxiv, 2020; 2020; 052530

26.. Wen W, Su W, Tang H, Immune cell profiling of COVID-19 patients in the recovery stage by single-cell sequencing: Cell Discov, 2020; 6(1); 31

Figures

In Press

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942770

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943214

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943010

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943687

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250