09 March 2022: Articles

Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma of Bartholin’s Gland: A Case Report with Emphasis on Surgical Management

Rare disease

Stephanie VertaDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.935707

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935707

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Adenoid cystic carcinomas of Bartholin’s gland are rare among gynecological malignancies, accounting for 0.1% to 7% of vulvar carcinomas and 0.001% of all female genital tract malignancies. There are no specific guidelines regarding treatment recommendations; therefore, they are commonly treated like vulvar cancer.

CASE REPORT: We present the case of a 42-year-old premenopausal woman with an adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland diagnosed upon biopsy of a palpable, predominantly vaginally located mass causing foreign-body sensation, vaginal pain, and extreme dyspareunia. The adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland was treated by radical resection in an extensive interdisciplinary surgical approach including bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection, partial posterior colpectomy, amputation of the rectum, and creation of a descendostomy, as well as reconstruction of the vagina and defect coverage using flap plastic.

CONCLUSIONS: With the presentation of this case, we propose a possible therapeutic approach to adenoid cystic carcinomas of Bartholin’s gland with emphasis on surgical management. Especially in young patients, we recommend primary radical surgery with the objective to obtain negative resection margins. However, additional data on the adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland is needed to better understand its biological behavior and thus optimize and standardize treatment. The role of systematic inguinal-femoral lymphadenectomy and adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatment modalities need further evaluation.

Keywords: Bartholin's Glands, Carcinoma, Adenoid Cystic, Surgical Flaps, Vulvar Neoplasms, Adult, Biopsy, Female, Humans

Background

Carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland is a rare malignant tumor of the female genital tract, subcategorized among the primary carcinomas of the vulva. It accounts for 0.1% to 7% of vulvar carcinomas and 0.001% of all female genital tract malignancies. Of all the possible histological subtypes of Bartholin’s gland carcinoma, the adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) of the Bartholin’s gland constitutes only about 10–15% and thus is an absolute rarity among gynecological tumors [1–7]. No more than approximately 350 cases have been reported in the literature [1,2].

Typically, ACCs occur in head and neck sites, such as the salivary glands, the lacrimal glands, the sinonasal region, and the pharynx, but they are also known to arise from other exocrine glands in rarer sites like the skin, the esophagus, the breast, or the uterine cervix [2,4,8,9]. ACCs of the head and neck region are typically characterized by slow, pervasive growth with often extensive perineural invasion, a tendency for local recurrences and distant metastasis, and are associated with poor prognosis [8,9]. Therefore, therapeutic management in this localization calls for wide local excision, and adjuvant radiotherapy is often needed [8].

Concerning the management of ACCs of Bartholin’s gland; however, no specific guidelines exist due to the lack of data on the natural history, the effect of therapeutic surgical and adjuvant strategies, and on prognosis in general. We therefore present the case of a 42-year-old premenopausal White woman who was referred to our tertiary care center for the treatment of a symptomatic, immobile tumor palpable primarily in the posterior wall of the vagina, without obvious mucosal involvement. The vulva itself appeared macroscopically intact. A biopsy taken from the tumor ultimately revealed an ACC of Bartholin’s gland.

The goal of this case report is, on the one hand, to share the process of the diagnostic workup and propose a possible therapeutic approach with emphasis on complete surgical excision and, on the other hand, to review the literature on the topic of ACCs of Bartholin’s gland with the objective to contribute to the existing body of literature on this rare tumor and help guide treatment for this specific tumor entity in the future.

Case Report

In November 2020, a 42-year-old premenopausal White woman was referred to our gynecological oncological outpatient unit due to a palpable mass in the posterior vaginal wall, suspicious for malignancy. The patient reported a foreign-body sensation in the vagina, which she had first perceived 3 months prior to her referral, as well as vaginal pain in a sitting position and extreme dyspareunia. Micturition was unimpaired, but defecation caused a sensation of pressure. She reported no hematochezia or irregular vaginal bleeding.

Her history included 2 spontaneous deliveries 14 and 11 years ago, an appendectomy in childhood, an operation on the detrusor muscle in childhood, a laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in 2013, and a laparoscopy due to a mechanical ileus in 2018. Her family history revealed 1 paternal aunt with breast cancer diagnosed at the age of 50.

Clinical examination revealed a hard, subepithelial tumor of the posterior vaginal wall, tender on palpation and fixed to the surrounding structures, starting at the vaginal introitus and extending 5 cm toward the uterine cervix, with a width of 3 cm. Although there was no obvious rectal infiltration on the rectal-vaginal exam, the tumor appeared to be at least adherent to the rectum at the level of the introitus. Ultrasound examination confirmed a tumorous lesion between the vaginal and rectal wall. An MRI scan revealed a contrast-enhancing tumor, suspicious for malignancy, originating from the posterior vaginal wall, measuring 34×27×37 mm. The tumor showed a semicircular growth pattern extending from 2 to 9 o’clock, infiltrating the musculus puborectalis on the left side and the musculus sphincter ani externus from 11 to 2 o’clock. Spiculated outgrowths of the tumor appeared to infiltrate the muscularis propria of the anterior rectal wall from 12 to 2 o’clock on imaging. The urethra did not seem infiltrated, and the uterus, the ovaries, the other pelvic organs, as well as the depicted bones, were without pathological findings. There were no pathologically enlarged lymph nodes (Figure 1A–1D).

A biopsy of the tumor was taken through the mucosa of the posterior vaginal wall in 3 locations. Histological workup revealed an adenoid cystic carcinoma with a break in the MYBGen (6q23) indicating a t (6;9) translocation, diagnostic of this tumor entity. A PET CT was performed to rule out primary metastatic disease. The tumor located in the posterior vaginal wall displayed moderate FDG activity and no other sites of disease were identified. A colonoscopy showed no evidence of infiltration of the rectal mucosa by the tumor.

The treatment strategy was discussed by an interdisciplinary team of experts. Considering the young age of the patient, primary surgical management with radical complete resection of the tumor was recommended to the patient. Alternatively, a neoadjuvant treatment was offered. The patient opted for the primary surgical approach, understanding that a permanent ostomy would most likely be necessary. The multidisciplinary surgery was planned by the gynecological oncologists along with the gastrointestinal and plastic surgeons. The operation included posterior partial colpectomy, rectal amputation and creation of a descendostomy, bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy, frozen section evaluation of the inguinal lymph nodes and, in case of positivity, bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy, as well as flap plastic surgery to reconstruct the introitus and vagina and cover the defect in the pelvic floor.

The intraoperative course was uneventful. Incisions were planned strategically and drawn in place. Initially, performed bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy resulted in tumor-free lymph nodes on frozen section. Subsequent laparoscopy revealed a normal-appearing uterus and bilateral adnexa without any pathological findings, as well as a smooth, lesion-free peritoneal surface (Figure 2A). Laparoscopic resection of the rectum was carried out by dissecting the mesorectum down to the level of the pelvic floor on the dorsal side (Figure 2B) and only partially into the recto-vaginal septum on the ventral side (to avoid cutting into the tumor and establishing a direct connection to the abdominal cavity). Following this step, the rectum was transected by stapler in the proximal to middle third for the later creation of a descendostomy.

Finally, the tumor itself was resected en-bloc together with the rectum and anus, as well as the levator ani muscles from a perineal approach in the sense of a posterior pelvic exenteration (Figures 3A–3D and 4A, 4B). Clinically, the tumor infiltrated into the middle third of the vagina, so that the upper third of the vagina including the uterus and ovaries could be preserved. Frozen section of the tumor-bearing specimen revealed a close surgical margin toward the dorsal vaginal wall at 12 o’clock, so that additional tissue was removed to ensure a tumor-free resection. The pelvic floor was then closed off by a Permacol® mesh attached cranially to the levator ani muscles (Figures 5 and 6A, 6B).

To complete the operation, the descendostomy was created in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen, and the vagina and the introitus were reconstructed with the help of bilateral posteromedial thigh (PMT) flaps and stalked flaps, which were also used to cover the tissue defect in the pelvic floor occurring due to the amputation of the rectum (Figures 7A–7D and 8). The patient remained hemodynamically stable during the entire procedure.

After a stay of 3 days in the intensive care unit, mainly due to initially complex nursing efforts, the patient returned to the normal gynecological ward, where the flaps and the wound were closely monitored. A focal superficial wound dehiscence located at the site of the former anus occurred on post-operative day 10 and was managed conservatively. The post-operative course was otherwise uncomplicated and uneventful. The patient was discharged from the hospital on post-operative day 15. She was closely followed as an outpatient to monitor the wound until secondary wound healing was complete.

The definitive histological examination of all the specimens confirmed the adenoid cystic carcinoma with a diameter of 45 mm, located in the posterior vaginal wall, growing around Bartholin’s gland of the left side (Figure 9), with infiltration of the perivaginal skeletal muscles, the tunica muscularis of the rectum, and the external and internal sphincter ani muscles. Further, perineural (Pn1) and microscopic venous invasion (V1) were present, whereas lymphatic vessels showed no signs of invasion (L0). Inguinal lymph nodes and pericolic lymph nodes located within the tumor-bearing specimen were negative. Finally, resection margins were declared tumor-free.

In conclusion and taking into account that the tumor clinically extended into the middle third of the vagina, the tumor stage according to UICC was: pT3 pN0 (0/6 inguinal lymph nodes on the left; 0/4 inguinal lymph nodes on the right) cM0 (no distant metastasis on PET scan) L0 V1 Pn1 R0; FIGO stage IVA. Regular follow-up was recommended by the interdisciplinary post-operative tumor board, with check-ups every 3 months during the first 3 years, every 6 months for the following 2 years, and once a year thereafter.

The clinical examination after 4 months displayed completely healed wounds with no signs of irritation (Figure 10). Finally, 8 months after surgery the patient remains recurrence-free, with good anatomical function of the neo-vagina and the ostomy, as well as a good quality of life. The timeline for the whole episode of care for this illness is shown in a diagram (Figure 11).

Discussion

Carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland is a rare malignancy of the vulva, accounting for 0.001% of all female genital tract malignancies, first documented by Klob in 1864 [3,5–7,10]. The various histological subtypes described so far include adeno-carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous cell carcinoma, transitional cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and undifferentiated adenocarcinoma [2–4,10–12]. Even sarcomas, melanomas, and undifferentiated tumors have been reported to arise from Bartholin’s gland [7,10,12]. However, the most common subtypes are the adenocarcinoma and the squamous cell carcinoma, which comprise approximately 90% of Bartholin’s gland neoplasms [7,10–12]. The mean age at diagnosis of a primary carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland is 50–60 years, with a range of 33–93 years [10]. Symptoms are nonspecific and include pain, swelling of the vulva, foreign-body or burning sensation, dyspareunia, feeling of pressure, or even abnormal bleeding [2–5,11,13]. Misdiagnosis is common, as these tumors mimic cysts or abscesses of Bartholin’s gland or sometimes even endometriosis, leading to a delay in diagnosis and treatment [3,5,7,11,13].

ACC of Bartholin’s gland account for only about 10–15% of all Bartholin’s gland carcinomas, with approximately 350 documented cases in the literature [1–5,7,13]. The mean age at diagnosis has been reported to be slightly younger, from 47 to 50 years, with a range from 25 to 80 years [1,3,4,11,13]. Pregnancy has been suggested to be an independent risk factor. Copeland et al observed that the tumor was associated with pregnancy in 7 out of 14 patients (50%) under the age of 42 years diagnosed with an ACC [14]. The most common symptoms of the ACC of Bartholin’s gland are pruritus, pain, or a burning sensation, most likely due to the characteristic tendency of this type of tumor to display perineural invasion [1,3–5,7,12,13]. These symptoms can occur long before a palpable mass becomes clinically evident [1,5,13].

ACCs of Bartholin’s gland are typically slow-growing, locally invasive tumors with a tendency for perineural and lymphatic vessel invasion, late local recurrence, and distant metastasis [3,5,7,13]. There appears to be a tendency toward local recurrence occurring before the development of distant metastasis [1,2,12,15]. The most common sites of distant metastasis are the lungs. However, metastasis to the bones, the liver, and the brain have been reported [2,3,5–7,12,15].

The course of disease of the ACC of Bartholin’s gland seems to differ somewhat from that of adenocarcinomas or squamous cell carcinomas of Bartholin’s gland in that metastatic spread to the local inguinal-femoral lymph nodes is uncommon [15].

According to Copeland et al, ACC of Bartholin’s gland has 5-, 10-, and 15-year progression-free survival rates of 47%, 38%, and 15%, respectively. Overall survival rates for 5, 10, and 15 years were calculated to be 71%, 50%, and 51% [14]. Lelle et al described a 5- and 10-year overall survival rate of 100% each, and a disease-free survival rate of 83% after 5 years and 33% after 10 years [12]. The longest reported survival is 31 years [1].

There currently is no consensus regarding the optimal treatment of ACC of Bartholin’s gland. The cornerstone, however, is complete surgical removal. Simple excision as well as simple and radical vulvectomy with or without lymph node dissection are the types of surgery that have most often been reported [7]. In our case, due to the unusual localization of ACC of Bartholin’s gland predominantly in the posterior vaginal wall, complete surgical removal, even if radical, did not include (hemi)vulvectomy. A literature review by Yang et al found that 68.9% of patients who had a simple excision of the tumor experienced a recurrence, compared to 42.9% of patients who underwent a radical vulvectomy [7]. Similar rates were calculated by DePasquale et al, who found a recurrence rate of 61% after local excision and 50% after radical vulvectomy [13]. Regarding the resection margins, Yang et al reported 48% positivity of the resection margin following simple excision and 30% positivity following radical vulvectomy. However, the information on the status of the resection margins was incomplete [7]. Looking at the 45 cases with available information on resection margins, the recurrence rates were 52.9% in the group with positive margins and 52.1% in the group with negative margins [7]. Lelle et al observed local recurrence in all (4) patients with negative margins [12]. Negative margins may therefore not be as predictive of local recurrence rates as previously assumed [14,15]. However, half of the patients in the positive margin group mentioned by Yang et al received adjuvant radiotherapy, thereby at least partially explaining the similar recurrence rates in both the negative and positive margin groups [7]. Hsu et al conducted a review including the cases mentioned by Yang et al as well as all reported cases in the 5 years following the publication by Yang et al. They were able to show that radical vulvectomy reduces local recurrence, but has no influence on the occurrence of distant metastasis [5].

There is controversy regarding the role of the inguinal-femoral lymph node dissection due to the observation that metastasis of ACC of Bartholin’s gland to inguinal-femoral lymph nodes is unusual, occurring in only about of patients 10% [12]. In the review by Copeland et al, metastatic disease to the lymph nodes were found in only 2 out of 15 patients undergoing inguinalfemoral lymphadenectomy [14]. In a slightly older review by Bernstein et al, only 1 of 9 patients treated with vulvectomy and bilateral inguinal-femoral lymphadenectomy had lymph node metastases [15]. Yang et al reported 2 cases with positive nodes in a total of 31 reported lymph node dissections in their review of the literature. In both cases, the lymph node metastases were located on the ipsilateral side of the tumor, and in 1 case the lymph node had been suspicious in a pre-operative CT. Furthermore, they reported a case of distant metastasis occurring before lymph node metastasis [7]. All in all, the limited data available in the literature on this topic suggest that the need for systematic inguinal-femoral lymphadenectomy should be carefully considered and discussed with the patient, and should potentially be limited to the ipsilateral side of the tumor or solely reserved for patients with clinically suspicious lymph nodes or for patients with a higher risk for lymph node involvement [7,11,12,15]. In our case, we discussed the topic of surgical lymph node staging, particularly its controversial role in ACC of Bartholin’s gland, extensively with the patient. The decision was made to carry out a bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy with frozen section evaluation and, in case of positivity, to perform bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy.

Radiotherapy has been used as an adjuvant treatment for ACC of Bartholin’s gland. It is particularly recommended when resection margins are positive or there is perineural invasion [2,5–7,13,15–17]. Bernstein et al suspected that ACC of Bartholin’s gland may be less sensitive to radiation therapy, because all of their reported patients with positive surgical margins died due to distant metastasis despite receiving adjuvant radiation treatment [15]. However, Copeland et al and Rosenberg et al showed good local control of the tumor using adjuvant external beam radiation in patients with positive resection margins and residual tumor, respectively [14,16]. A review by Yang et al reported on 15 patients treated by adjuvant radiotherapy, 9 of whom had positive margins and experienced no local recurrence; however, 5 of the 9 patients with positive margins developed distant metastasis. They concluded that adjuvant radiotherapy seems to decrease the risk of local recurrence when there are positive margins [7].

There is no consensus concerning the total dose of radiation needed. In the literature, the total doses applied were reported to range from 50.4 to 63 Gy. Agolli et al applied a total of 56 Gy in 28 fractions, Makhija et al a total of 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions, Momeni et al a total of 50.4 Gy in 30 fractions, and Goh et al a total of 63 Gy in 33 fractions [17–20]. Special considerations in the indication of adjuvant radiation therapy have to be made for premenopausal women who want to continue childbearing. In the case of our patient, taking into consideration the radical resection with negative margins and the lack of data showing a benefit in such cases, adjuvant radiotherapy was not recommended and thus was not applied. The young age of the patient and the possible negative effects of radiation on the vulva and vagina and thus on sexual function, especially after plastic reconstruction, also led to the decision not to administer adjuvant radiotherapy.

As for primary radiation or primary chemoradiation, no clear statement can be made regarding the effect on the ACC of the Bartholin’s gland. Lopez-Varela et al published a retrospective review investigating the outcome after primary radiation or primary chemoradiation treatment of 10 cases of Bartholin’s gland carcinoma in general and including 2 cases of ACC. Radiotherapy included teletherapy, with or without boost to the primary site as well as the regional nodes, and with or without interstitial brachytherapy. In the case of primary chemoradiation, the chemotherapeutical agent was cisplatin, which was applied in 2 of the 10 cases of Bartholin’s gland carcinoma. The median follow-up was 87.2 months (45–142). They found that the 3- and 5-year survival rates were 71.5% and 66%, respectively, and thus were comparable with outcomes after primary surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy. The authors concluded that primary radiation or chemoradiation is an effective and appropriate alternative to surgery, with lower morbidity and the possibility to preserve genital and sexual function [21]. In our case, we opted against primary chemoradiation for 2 reasons: because the patient was young and in good enough condition to tolerate an extensive surgery, and because radiotherapy and especially interstitial brachytherapy can cause vaginal stenosis and thus have a detrimental effect on sexuality. A further consideration was the possibility of local recurrence later on, where, after primary surgical management, a residual radiation capacity is left to treat the recurrence. However, after primary chemoradiation, for the most part, no residual radiation capacity is left, and salvage surgery after radiation is associated with high morbidity.

For patients in whom the (recurrent) tumor is inoperable or when complete resection is not achievable (hence in a locally advanced stage of ACC), Bernhardt et al reported promising treatment responses with photon intensity-modulated radio-therapy (IMRT) plus carbon ion (C12) boost as primary as well as adjuvant treatment. The tolerability of this bimodality treatment was good and toxicity was low. However, a larger cohort of similarly treated patients and a longer follow-up are needed to validate the efficacy of this treatment option [1,22]. A review by Loap et al nicely summarized that carbon ion radiation therapy (CIRT) can achieve substantial tumor control, explaining why CIRT is becoming an increasingly applied irradiation modality for ACC in light of its intrinsic radioresistance [1,23].

Concerning the role and administration of adjuvant chemo-therapy in ACC of Bartholin’s gland, there is even less evidence of the effectiveness compared to radiation therapy and there is no consensus. Chemotherapy was administered mostly in the setting of recurrent, metastatic disease. No specific chemotherapy regimen has been established so far. Abrao et al reported on administering a combination of cyclophosphamide and adriamycin to 2 patients with lung metastasis; unfortunately, with no description of the outcome [24]. Yang et al described achieving stable disease by administering 6 cycles of cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, and cisplatin in 1 patient with lung metastasis [7]. Lelle et al reported giving cyclophosphamide to 1 patient in an adjuvant setting after wide excision. The patient lived for another 15 years [12]. Yoon et al administered 6 cycles of adriamycin and cisplatin to 1 patient with pulmonary metastasis, achieving stable disease. Another patient received 6 cycles of palliative chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, and cisplatin, but liver metastasis occurred shortly thereafter [25]. Further chemo-therapeutic agents that have been used in the therapy of ACC of Bartholin’s gland include paclitaxel, methotrexate, doxorubicin, 5-fluorouracil, dactinomycin, chlorambucil, and irinotecan [7,12,16,17,25,26].

Anti-estrogen therapy of ACC of Bartholin’s gland has been used in all but 1 case to present. Hsu et al described the case of 1 patient in whom stable disease was achieved over 4 years with the help of tamoxifen [5].

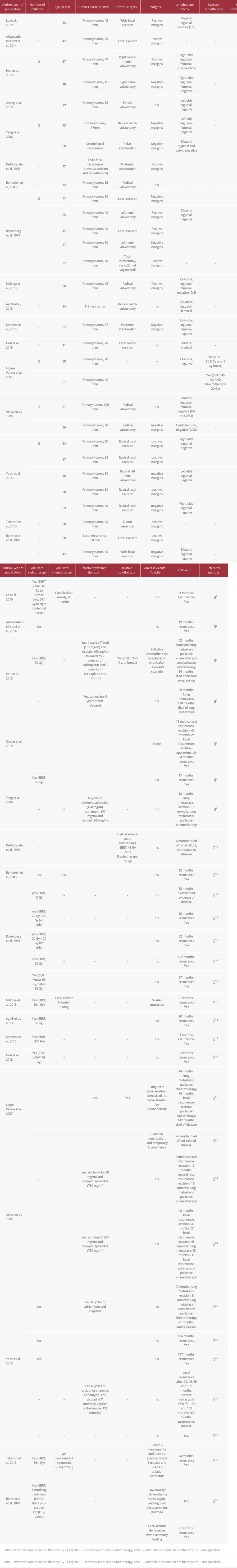

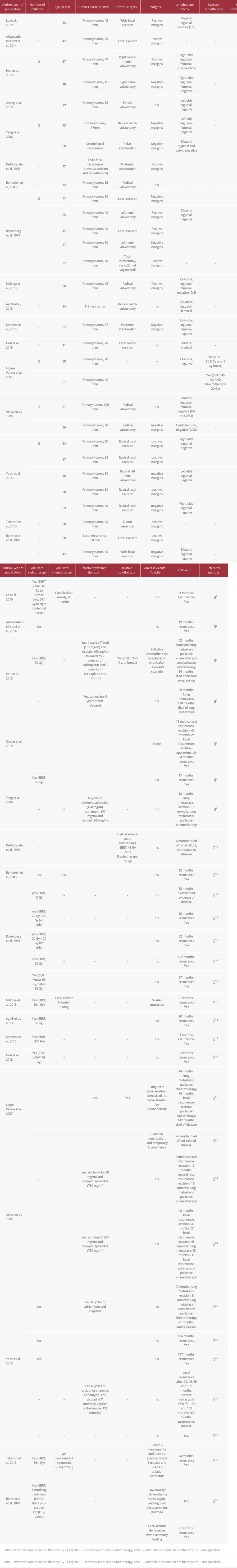

Table 1 provides an overview of 30 cases of ACC of Bartholin’s gland reported on in the references [2,3,5–7,13,15–22,24–26]. The age at diagnosis ranged from 32 to 77 years and the mean age was 50.83 years. As shown, in most of the cases (28/30, 93%) upfront surgery was the primary treatment method of choice. Lymph node dissection was performed in 64% (18/28) of the primarily operated cases and in 61% (11/18) it was done only ipsilaterally. Metastatic spread to the lymph nodes at the time of surgery was present in 2 out of 18 cases (11.1%).

Of the 28 cases that had undergone upfront surgery, 18 (64%) received adjuvant radiotherapy. In 27.8% of these cases (5/18), adjuvant radiotherapy was administered despite negative re-section margins (in 2 cases receiving adjuvant radiotherapy no information on the resection margins was provided). However, regarding the cases with positive resection margins, all of the patients received adjuvant radiotherapy (except for 1 reported by DePasquale et al, who had a third recurrence, having received palliative radiotherapy 6 years earlier [13]). Adjuvant radiotherapy consisted of external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) in all cases; in 1 of the 18 cases it was in form of a bimodality treatment with photon IMRT plus carbon ion boost [22]. No brachytherapy was applied in the adjuvant setting. Three cases (7.1%) underwent adjuvant chemoradiation, in 2 cases cisplatin was administered, and in 1 case irinotecan was the chemotherapeutic agent of choice. In all of these 3 cases re-section margins had been positive beforehand.

Only 2 of the 30 cases (6.7%) described in Table 1 were treated by upfront radiotherapy. In 1 case the patient received EBRT, and the other received EBRT plus brachytherapy. Primary chemoradiation was not administered in any of the cases.

Eighteen of the 30 patients were reported to be recurrence-free during the observation period; however, follow-up was relatively short in many cases, ranging from 3 to 162 months. The longest recurrence-free follow-up of 162 months was reported by Rosenberg et al. In this case, the primary tumor was only 10 mm in diameter, wide excision by hemi-vulvectomy was performed, achieving negative margins, and adjuvant radiotherapy was administered [16]. Recurrent disease was observed in 9 out of 30 cases (30%). Local recurrence was observed after 9–54 months, which means that the mean recurrence-free interval was 29.6 months. Distant metastasis was reported to occur after 7–71 months, the mean time to appearance being 37.7 months. Four of the 9 cases with recurrent disease had both local recurrence and distant metastasis. The most frequently reported site of distant metastasis was the lung, but metastases to the liver and the bones were also described. In all of the 8 cases with distant metastasis, palliative systemic therapy was administered. Seven patients received palliative chemotherapy, consisting of adriamycin and cyclophosphamide with or without cisplatin in the most cases. In 1 case, tamoxifen was the agent of choice (the patient had refused chemotherapy) [5].

Although there have been few reports on toxicity for all the therapeutic modalities, in those cases where information was provided, the toxicity was mostly low. In 1 case, however, anaphylaxis was reported following administration of taxol and cisplatin.

ACC of Bartholin’s gland is a tumor with an excellent long-term overall survival but has a tendency for local and distant recurrence, often occurring long after primary therapy. Surgery is the primary treatment of choice, and negative margins are probably associated with a lower risk for local recurrence. However, adjuvant radiation therapy in patients with positive margins seems to result in similar recurrence rates. Inguinal-femoral lymphadenectomy as part of the surgical procedure should be carefully considered since lymphogenic metastatic spread is rather untypical for ACC of Bartholin’s gland. While primary radiation and chemoradiation can be an option, especially for patients not suitable for surgery, the place and value of chemotherapy and anti-hormone therapy need further investigation.

Conclusions

Because adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland is a rarity among malignant tumors of the female genital tract, no specific consensus or guidelines exist regarding treatment recommendations. Therefore, therapeutic management currently calls for an individualized interdisciplinary approach extrapolated from knowledge of the biological behavior of ACC in the more common head and neck region, as well as from the guidelines on vulvar cancer, especially regarding the pathways of lymphatic spread. However, it must be considered that the biological behavior and course of disease of an ACC of Bartholin’s gland is somewhat different from typical vulvar cancer.

Based on the available literature on ACC of Bartholin’s gland and considering our case, complete surgical removal with negative margins should be regarded as the primary treatment modality of choice, especially in young patients. In our patient, the surgical procedure to achieve radical resection included posterior partial colpectomy, rectal amputation (due to radiologically suspected infiltration of the musculus sphincter ani externus and muscularis propria of the anterior rectal wall), creation of a descendostomy, and reconstruction of the introitus and vagina, as well as coverage of the defect in the pelvic floor by means of reconstructive flap surgery. Loco-regional lymphadenectomy, in our patient carried out by bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection with frozen section evaluation, is still a controversial topic in surgical treatment of ACC of Bartholin’s gland; therefore, it should be discussed individually with the patient. The role of adjuvant treatment such as radiotherapy also remains unclear, and should probably be limited to patients with positive margins or incomplete resection. In our case, consequently, it was not performed. Primary chemoradiation is a possible therapeutic option, with seemingly comparable outcomes. However, especially in young premenopausal patients like ours, special considerations have to be made regarding long-term sexual function and therapeutic options in the case of recurrence.

Clearly, additional data are needed on ACC of Bartholin’s gland to better understand its biological behavior and thus define prognostic factors to optimize treatment planning with the objective to standardize the therapeutic approach. Especially, the roles of systematic inguinal-femoral lymphadenectomy as well as adjuvant and neoadjuvant radiotherapy and chemoradiation, respectively, need further evaluation. Nonetheless, the management of a rare tumor in such a location should always be tailored to patient age, sexual activity, and general health.

Figures

References:

1.. Barcellini A, Gadducci A, Laliscia C, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland: What is the best approach?: Oncology, 2020; 98(8); 513-19

2.. Lo CCW, Leow JBY, Naing K, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the Bartholin’s gland: A diagnostic dilemma: Case Rep Obstet Gynecol, 2019; 2019; 1784949

3.. Akbarzadeh-Jahromi M, Sari Aslani F, Omidifar N, Amooee S, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland clinically mimics endometriosis, a case report: Iran J Med Sci, 2014; 39(6); 580-83

4.. Ramanah R, Allam-Ndoul E, Baeza C, Riethmuller D, Brain and lung metastasis of Bartholin’s gland adenoid cystic carcinoma: A case report: J Med Case Rep, 2013; 7(1); 208

5.. Hsu S-T, Wang R-C, Lu C-H, Report of two cases of adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland and review of literature: Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol, 2013; 52(1); 113-16

6.. Chang Y, Wu W, Chen H, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the Bartholin’s gland: A case report and literature review: J Int Med Res, 2020; 48(2); 300060519863540

7.. Yang S-YV, Lee J-W, Kim W-S, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the Bartholin’s gland: Report of two cases and review of the literature: Gynecol Oncol, 2006; 100(2); 422-25

8.. Sood S, McGurk M, Vaz F, Management of salivary gland tumours: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines: J Laryngol Otol, 2016; 130(S2); S142-49

9.. Gondivkar SM, Gadbail AR, Chole R, Parikh RV, Adenoid cystic carcinoma: A rare clinical entity and literature review: Oral Oncol, 2011; 47(4); 231-36

10.. Ouldamer L, Chraibi Z, Arbion F, Bartholin’s gland carcinoma: Epidemiology and therapeutic management: Surg Oncol, 2013; 22(2); 117-22

11.. Woida FM, Ribeiro-Silva A, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the Bartholin gland: An overview: Arch Pathol Lab Med, 2007; 131(5); 796-98

12.. Lelle RJ, Davis KP, Roberts JA, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the Bartholin’s gland: The University of Michigan experience: Int J Gynecol Cancer, 1994; 4(3); 145-49

13.. DePasquale SE, McGuinness TB, Mangan CE, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland: A review of the literature and report of a patient: Gynecol Oncol, 1996; 61(1); 122-25

14.. Copeland LJ, Sneige N, Gershenson DM, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin gland: Obstet Gynecol, 1986; 67(1); 115-20

15.. Bernstein SG, Voet RL, Lifshitz S, Buchsbaum HJ, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland. Case report and review of the literature: Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1983; 147(4); 385-90

16.. Rosenberg P, Simonsen E, Risberg B, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland: A report of five new cases treated with surgery and radiotherapy: Gynecol Oncol, 1989; 34(2); 145-47

17.. Makhija A, Desai AD, Patel BM, Parekh CD, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s Gland misdiagnosed as benign vulvar adnexal tumour: Indian J Gynecol Oncol, 2018; 16(1); 1

18.. Agolli L, Osti MF, Armosini V, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland receiving adjuvant radiation therapy: Case report: Eur J Gynaecol Oncol, 2013; 34(5); 487-88

19.. Momeni M, Korotkaya Y, Carrasco G, Prasad-Hayes M, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland: Case report: Acta Med Iran, 2016; 54(12); 820-22

20.. Goh SP, McCully B, Wagner MK, A case of adenoid cystic carcinoma mimicking a Bartholin cyst and literature review: Case Rep Obstet Gynecol, 2018; 2018; 5256876

21.. López-Varela E, Oliva E, McIntyre JF, Fuller AF, Primary treatment of Bartholin’s gland carcinoma with radiation and chemoradiation: A report on 10 consecutive cases: Int J Gynecol Cancer, 2007; 17(3); 661-67

22.. Bernhardt D, Sterzing F, Adeberg S, Bimodality treatment of patients with pelvic adenoid cystic carcinoma with photon intensity-modulated radiotherapy plus carbon ion boost: A case series: Cancer Manag Res, 2018; 10; 583-88

23.. Loap P, Vischioni B, Bonora M, Biological rationale and clinical evidence of carbon ion radiation therapy for adenoid cystic carcinoma: A narrative review: Front Oncol, 2021; 11; 789079

24.. Abrao FS, Marques AF, Marziona F, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland: Review of the literature and report of two cases: J Surg Oncol, 1985; 30(2); 132-37

25.. Yoon G, Kim H-S, Lee Y-Y, Analysis of clinical outcomes of patients with adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin glands: Int J Clin Exp Pathol, 2015; 8(5); 5688-94

26.. Takatori E, Shoji T, Miura J, Chemoradiotherapy with irinotecan (CPT-11) for adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland: A case report and review of the literature: Gynecol Oncol Case Rep, 2013; 4; 16-19

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Overview of the case characteristics, therapeutic modalities, treatment toxicity, and follow-up in cases of ACC of the Bartholin’s gland described in the literature references [2,3,5–7,13,15–22,24–26].

Table 1.. Overview of the case characteristics, therapeutic modalities, treatment toxicity, and follow-up in cases of ACC of the Bartholin’s gland described in the literature references [2,3,5–7,13,15–22,24–26]. Table 1.. Overview of the case characteristics, therapeutic modalities, treatment toxicity, and follow-up in cases of ACC of the Bartholin’s gland described in the literature references [2,3,5–7,13,15–22,24–26].

Table 1.. Overview of the case characteristics, therapeutic modalities, treatment toxicity, and follow-up in cases of ACC of the Bartholin’s gland described in the literature references [2,3,5–7,13,15–22,24–26]. In Press

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942032

06 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942937

12 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943244

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943275

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250