26 October 2022: Articles

Coronary Subclavian Steal Syndrome in a 73-Year-Old Woman Presenting with Angiographically Confirmed Subclavian Artery Stenosis Proximal to the Left Internal Mammary

Challenging differential diagnosis, Management of emergency care, Clinical situation which can not be reproduced for ethical reasons, Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Jared Steinberger1ABCDEFG*, Fawaz Georgie1ABCDE, Marcel Zughaib1ABCDEFDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.937015

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e937015

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Coronary subclavian steal syndrome (CSSS) is an uncommon condition in which a high-grade stenosis of the subclavian artery proximal to an internal mammary artery bypass graft results in retrograde blood flow of the bypass graft. This report is of CSSS in a 73-year-old woman who presented with ventricular tachycardia and angiographically confirmed subclavian artery stenosis proximal to the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) bypass graft 3 years following coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

CASE REPORT: The patient was a 73-year-old woman with a past medical history of multivessel coronary artery disease, found on preoperative evaluation. She underwent 2 vessel CABG in 2018. She was found to have ischemic cardiomyopathy, ejection fraction of 30% to 35% despite revascularization, and an implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD). Three years following uncomplicated CABG, the patient presented with angina and sustained ventricular tachycardia; ICD therapy was unsuccessful. Ischemia was the etiology of the sustained ventricular tachycardia, and the patient underwent cardiac catheterization, demonstrating high-grade subclavian artery stenosis proximal to the LIMA bypass graft. Intervention of the 80% lesion of the native left anterior descending artery was done with placement of a 2.75×16-mm drug-eluting stent. The patient responded well to treatment, with no subsequent ventricular tachycardia on outpatient follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS: This report has shown that in patients who present with symptoms of acute coronary syndrome and a history of CABG involving the LIMA, the possibility of CSSS should be considered and investigated by coronary artery imaging so that diagnosis and management are not delayed.

Keywords: Coronary Artery Disease, Female, Humans, Aged, Subclavian Steal Syndrome, Coronary-Subclavian Steal Syndrome, drug-eluting stents, Coronary Artery Bypass, Tachycardia, Ventricular

Background

The steal phenomenon of the human vasculature is well described in the medical literature, with the underlying principle of low resistance arteries encouraging flow from high-pressure systems [1]. Clinical presentations of steal physiology can range from asymptomatic to hypoperfusion of the affected end organ; in the case of subclavian steal, near syncope or syncope can be the presenting symptom [2].

In the event of proximal subclavian artery stenosis, the vertebral artery and internal mammary artery (IMA) can fill the subclavian artery in a retrograde fashion [3]. Flow reversal of the IMA would be asymptomatic because of the end organ supply of the anterior chest wall; however, in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), the IMA is a commonly used conduit to supply the coronary arteries [4]. Most frequently in clinical practice, the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) is used as a conduit to the left anterior descending artery (LAD). In coronary subclavian steal syndrome (CSSS), flow reversal of a LIMA graft can occur, resulting in myocardial ischemia to the supplied coronary artery [5].

The diagnosis of CSSS can be made clinically in symptomatic patients with prior IMA bypass grafting and with a difference in systolic blood pressure of the upper extremities, with the affected extremity >15 mm Hg higher than the unaffected [1]. A bruit can be auscultated near the clavicle of the affected IMA on physical examination [2]. Imaging modalities, including computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and invasive angiography, can confirm the diagnosis of CSSS and provide for intervention planning. Careful attention must be given to the takeoff of the vertebral artery and IMA to ensure possible plaque migration does not compromise these vessels [3].

Case Report

A 73-year-old woman had a past medical history of multivessel coronary artery disease found on preoperative evaluation 3 years prior to presentation. The patient underwent 2 vessel CABG for stable ischemic heart disease in 2018 (LIMA-LAD, SVG-OM1). The patient was found to have ischemic cardiomyopathy, ejection fraction of 30% to 35% despite revascularization, and an implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD), implanted for primary prevention at that time. Three years following un-complicated CABG, the patient presented with angina and sustained ventricular tachycardia, with unsuccessful ICD therapy. A 12-lead electrocardiogram was unavailable because of the hemodynamically unstable wide complex tachycardia, which was consistent with ventricular tachycardia seen on telemetry. The patient was converted to sinus rhythm with manual anti-tachycardia pacing at bedside. After stabilizing the patient’s ventricular tachycardia, further investigation was spent on the etiology of the angina on presentation and the sustained ventricular tachycardia. Ischemia was thought to be the driving factor, and the patient underwent cardiac catheterization for further assessment of her bypass grafts and coronary anatomy (Figures 1, 2).

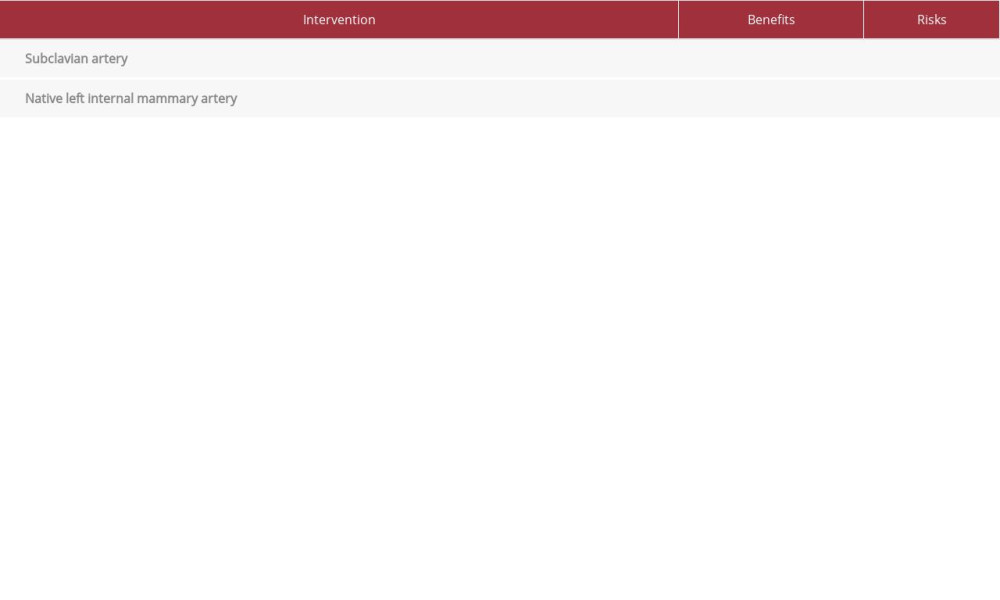

The dilemma of whether to revascularize the subclavian artery or the native LAD was considered (Table 1). Given the risk of a close proximity of the subclavian plaque with the possibility of plaque migration, as well as the acute presentation, intervention of the native LAD 80% lesion was done with placement of a 2.75×16-mm drug-eluting stent. The patient’s immediate course after the procedure was uncomplicated, with resolution of the ventricular tachycardia. The patient was followed by the Cardiology Department in the outpatient setting for monitoring of medical therapy and clinical response to native LAD intervention.

Discussion

The comparison of the revascularization of the subclavian artery versus revascularization of the native LAD is shown in Table 1, which is the main lesson from this challenging case. At our institution, the subclavian artery is routinely assessed for stenosis prior to CABG; however, this varies by surgeon preference. The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association have not released guidelines on the management of CSSS. The European Society of Cardiology 2017 guidelines recommend endovascular revascularization in symptomatic patients at a class I, evidence C level [6]. In patients for whom the ostium of vertebral arteries and IMA is in close proximity to subclavian artery stenosis and plaque migration is a concern, there remains an option for surgical revascularization [7]. Plaque migration and embolization of contents can be devastating, with vertebral embolization resulting in posterior circulation stroke, and IMA embolization resulting in graft closure or myocardial infarction [8,9]. Medical therapy following intervention regardless of approach must be focused on management of cardiovascular comorbidities to prevent further disease progression.

After careful consideration of the patient’s native coronary anatomy and steal physiology, close proximity of the subclavian plaque with concerns of plaque migration, and acute presentation, the intervention of the native LAD 80% lesion was done with placement of a 2.75×16-mm drug-eluting stent. The patient’s immediate course after the procedure was uncomplicated, with no further episodes of chest pain or ventricular tachycardia. The patient was followed by the Cardiology Department in the outpatient setting for monitoring and to discuss staged subclavian artery intervention in the near future.

Conclusions

This report has shown that in patients who present with symptoms of acute coronary syndrome and a history of CABG involving the LIMA, the possibility of CSSS should be considered and investigated by coronary artery imaging so that diagnosis and management are not delayed. Medical therapy of comorbidities is crucial in these patients to minimize risk of disease progression.

Figures

References:

1.. Lak HM, Shah R, Verma BR, Roselli E, Coronary subclavian steal syndrome: A contemporary review: Cardiology, 2020; 145(9); 601-7

2.. Cua B, Mamdani N, Halpin D, Review of coronary subclavian steal syndrome: J Cardiol, 2017; 70(5); 432-37

3.. Ochoa VM, Yeghiazarians Y, Subclavian artery stenosis: A review for the vascular medicine practitioner: Vasc Med, 2010; 16(1); 29-34

4.. Goldman S, Zadina K, Moritz T, Long-term patency of saphenous vein and left internal mammary artery grafts after coronary artery bypass surgery: J Am Coll Cardiol, 2004; 44(11); 2149-56

5.. Sintek M, Coverstone E, Singh J, Coronary subclavian steal syndrome: Curr Opin Cardiol, 2014; 29(6); 506-13

6.. Halliday A, Bax JJ, The 2017 ESC Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases, in Collaboration With the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS): Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg, 2018; 55(3); 301-2

7.. Haj Bakri M, Nasser M, Al Saqer L, Endovascular treatment of coronary subclavian steal syndrome complicated with STEMI and VF: A case report and review of the literature: Clin Case Rep, 2018; 6(12); 2482-89

8.. Arboine L, Palacios JM, Jauregui O, Coronary-subclavian steal syndrome: An infrequent cause of ischemia post coronary artery bypass graft surgery: J Med Case, 2017; 8(8); 256-58

9.. Walensi M, Bernheim J, Ulatowski N, Atypical and rare cause of myocardial infarction: coronary subclavian steal syndrome (CSSS) treated by a carotid-subclavian bypass in a 71-year-old female patient: J Cardiothorac Surg, 2021; 16(1); 237

Figures

In Press

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942826

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942770

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943214

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943010

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250