29 August 2022: Articles

An Unusual Presentation of Adrenocortical Carcinoma (ACC): Panic Attacks and Psychosis

Unusual clinical course, Challenging differential diagnosis, Rare disease, Educational Purpose (only if useful for a systematic review or synthesis)

Yassine KilaniDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.937298

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e937298

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) is a very rare disease, with an incidence of 1.02 per million population per year. The most commonly secreted hormone in ACC is cortisol, often presenting as a rapidly progressive Cushing syndrome (CS). We describe a case of ACC with an unusual presentation, mainly with psychiatric manifestations, including panic attacks and hallucinations.

CASE REPORT: A 52-year-old woman presented with episodes of acute anxiety, hallucinations, palpitations, hot flashes, gastrointestinal upset associated with paroxysmal hypertension, tachycardia, and flushing for 1 week. The initial workup was aimed at ruling out causes of acute psychosis and/or anxiety such as substance use, and organic diseases such as pheochromocytoma (PCC). Our initial suspicion of PCC was ruled out based on the negative serum and urinary metanephrines (MN) and normetanephrines (NMN). Recurrent metabolic alkalosis and hypokalemia despite fluid and potassium supplementation prompted us to work up for hyperaldosteronism. Her renin level was elevated and the aldosterone level was appropriately suppressed. Elevated cortisol, positive dexamethasone (DXM) suppression test, low adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), imaging revealing an adrenal mass, and postoperative histology confirmed the diagnosis of cortisol-producing ACC.

CONCLUSIONS: It is essential to recognize psychiatric presentations of CS to achieve early diagnosis and prevent mortality and morbidity. Panic attacks, a common presentation of CS, can present with features mimicking pheochromocytoma (PCC), including palpitations, sweating, tachycardia, and paroxysmal hypertension. A comprehensive workup is warranted to reach a diagnosis, with a combination of hormonal levels, imaging, and histology.

Keywords: adrenocortical carcinoma, Cushing Syndrome, panic disorder, Pheochromocytoma, Adrenal Cortex Neoplasms, Adrenal Gland Neoplasms, Female, Hallucinations, Humans, Hydrocortisone, Hypertension, Middle Aged, Psychotic Disorders

Background

Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) is a very rare disease, with an incidence of 1.02 per million population per year in a population-based study in the United States [1]. Up to 60% of patients with ACC present with symptoms of adrenal steroid hormone excess [2]. The most commonly secreted hormone in ACC is cortisol, often presenting as a rapidly progressive Cushing syndrome [3,4]. We describe a case of ACC with an unusual clinical presentation, mainly with psychiatric manifestations, including panic attacks and hallucinations, associated with paroxysmal hypertension, tachycardia, flush, and hot flashes.

Case Report

HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS:

Our patient was a 52-year-old woman who was brought in by Emergency Medical Services, accompanied by her sister due to acute episodes of anxiety and aggressive and bizarre behavior at home that started during the previous week. These episodes were accompanied by increased sweating, hot flashes, flushing, palpitations, and gastrointestinal upset, without any identifiable precipitating factor. She denied any prior similar episode in the past. She endorsed a 9-kg weight loss over the last 3–4 months. She denied headaches, visual changes, loss of consciousness, tremors, weakness, chest pain, shortness of breath, diarrhea, easy bruising, striae, arthralgia, and myalgia.

PAST MEDICAL HISTORY:

Her past medical history was significant for recently diagnosed hypertension (weeks prior) and diabetes mellitus (DM) (months prior). She and her sister denied any personal or family history of psychiatric disorders (including mood disorders, psychotic disorder, substance use disorders, psychiatric hospitalizations, and suicide attempts). She had a surgical history of total abdominal hysterectomy and cholecystectomy years prior. Her family history included a father with diabetes mellitus, and renal cancer in another sister (now deceased). Her medications included lisinopril, metformin, and glimepiride. Glimepiride was switched to ertugliflozin following an episode of hypoglycemia. She denied alcohol use, smoking, or illicit drug use.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION:

Initial physical examination showed a temperature 37.2°C, a blood pressure of 135/86 mmHg, a heart rate of 115/min, a respiratory rate of 18/min, and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. Body mass index (BMI) was 22.17 kg/m2. The patient was alert and oriented to time, place, and person. She was anxious, tearful, and appeared to have intermittent visual hallucinations along with persecutory and psychotic delusions. Skin inspection revealed flushing of the face and the chest, without any visible lesions. The chest was clear on auscultation bilaterally, with normal heart sounds, a soft abdomen with mild epi-gastric tenderness, and no edema. She was placed on continuous telemetry for monitoring of her vital signs.

LABORATORY WORKUP:

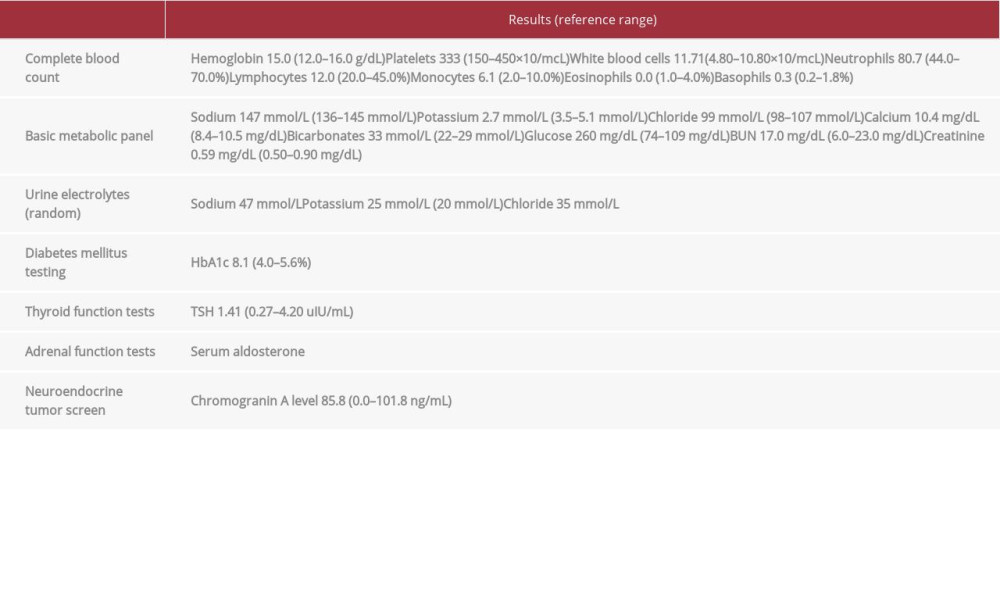

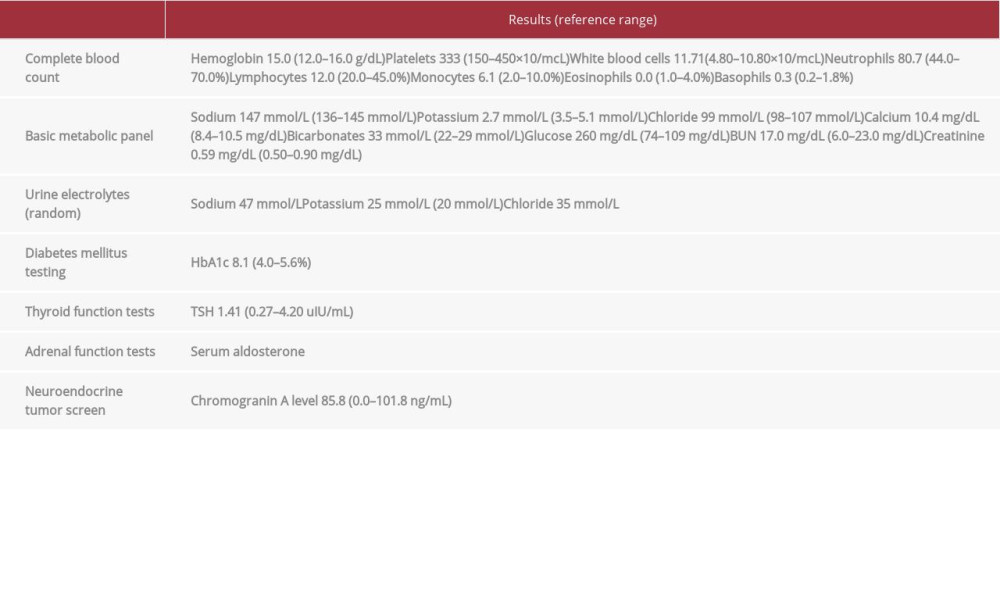

An ECG showed sinus tachycardia (115 beats/min), with possible right atrial enlargement (RAE), and left ventricular hyper-trophy (LVH) with repolarization changes (Figure 1). A comprehensive urine drug screen panel was negative. Laboratory findings are summarized in Table 1. Our differential diagnoses for leukocytosis, lymphopenia, and neutropenia included infection, autoimmune disease, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection, and hypercortisolism. Urinalysis was positive (positive leukocyte esterase, nitrites, leukocyturia, bacteriuria), so a urine culture was performed. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and anti-double stranded DNA (DsDNA) were negative and ruled out systemic lupus erythematosus. Hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis prompted us to screen for causes of hyperaldosteronism. Further laboratory workup ruled out primary/secondary hyperaldosteronism and pheochromocytoma (Table 1). The diagnosis of CS was made based on elevated 24-h free urinary cortisol, elevated serum AM Cortisol at 37.9 mcg/dL, and positive dexamethasone (DXM) suppression test (inappropriate suppression of morning serum cortisol after 1 mg DXM administration: 30 ug/dL). ACTH level was low, indicating a peripheral cause of CS.

IMAGING:

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head without contrast was unremarkable, with the exception of mild diffuse cerebral atrophy. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis showed a right adrenal heterogeneous mass with calcifications (Figure 2). Differential diagnoses for this mass included adrenal carcinoma, pheochromocytoma, or, less likely, lipid poor adenoma. CT of the chest with contrast revealed a 4-mm semisolid left lower lung lobe nodule and an 8-mm ground-glass nodule in the right upper lobe.

TREATMENT AND FOLLOW-UP:

Prior to the diagnosis, the patient was medically managed with intravenous (i.v.) fluids and electrolytes repletion, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) for urinary tract infection, amlodipine and lisinopril for hypertension, labetalol for tachycardia, insulin for DM, and antipsychotics. After the diagnosis of ACC was suspected based on the imaging and the hormonal panel, she was medically cleared for surgery and underwent a right adrenal tumor resection.

To prevent postoperative adrenal insufficiency, the patient received an initial dose of i.v. hydrocortisone (HC) 50 mg every 4 h on the surgery day, which was tapered down on postoperative days 1, 2, and 3 to 50 mg every 6, 8, and 12 h, respectively. On day 4, she received oral HC 50 mg at 8 AM, and 25 mg at 4 PM. She was discharged on the same day, and continued on oral HC 25 mg twice daily and potassium supplementation. The postoperative course was uncomplicated, with resolution of the psychiatric and cardiovascular symptoms. She was alert, calm, and oriented, with a normal blood pressure of 105/65 mmHg and heart rate of 74/min at follow-up.

Histology results available after 8 days were consistent with low-grade ACC with a free tumor margin. Tumor cells were positive for SF-1, Melan-A, and Inhibin and negative for INSM1 and chromogranin. A PET-CT scan showed no evidence of lymph node or bone metastasis, and revealed a mildly hypermetabolic pulmonary nodule and a right upper lobe ground-glass nodule without FDG uptake, both possibly neoplastic. She continues to follow up with Endocrinology, Cardiology, and Oncology. Further germline testing of the tumor is pending.

Discussion

Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) is a very rare disease, with an incidence ranging from 0.72 to 2 per million population per year [1,4–6]. Most cases are sporadic, while some are inherited due to genetic mutations (MEN-1, Li-Fraumeni, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, Lynch syndrome) [7].

Most ACCs are functional, and present with symptoms of steroid hormone excess [2]. The most commonly secreted hormone is cortisol, resulting in Cushing syndrome (CS). In patients with ACC, the clinical symptoms tend to develop rapidly, usually over 3–6 months [4]. Diagnosing CS can be difficult due to its wide range of manifestations, including dermatologic (acne, facial plethora/flushing, thin skin, easy bruising, purple striae over the abdomen, and hirsutism), musculo-skeletal (proximal muscle weakness and atrophy, and osteoporosis), psychiatric (psychosis, panic disorder, depression, and irritability), immunological (susceptibility to infection, neutrophilia, and eosinopenia), and metabolic or endocrine (weight gain, fat redistribution with buffalo hump and moon face, hypertension, glucose intolerance, dyslipidemia, electrolyte imbalances, amenorrhea in women, and decreased libido in both genders) [8].

Our patient had a recent history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and weight loss within months prior to admission. The usual weight gain seen in patients with CS is commonly replaced by weight loss in ACC [9]. She presented with acute onset and recurrent episodes of psychosis, panic attacks, paroxysmal hypertension, tachycardia, flushing, and sweating. After ruling out substance use, differential diagnoses included panic disorder (PD) and PCC. A full laboratory evaluation was warranted to exclude PCC. The diagnosis of PCC is based on the serum and urine metanephrines, and imaging of the adrenal glands [10].

During our literature review, we tried to identify cases of CS that presented with paroxysms of hyperadrenergic symptoms. Reports of adrenal tumors combining features of CS and PCC are available, the most common being ACTH producing PCC, which is a rare cause of ectopic ACTH syndromes (3%) [11], and numerous cases have been reported [12–16]. However, such cases have elevated serum/urinary metanephrines, normetanephrines, and elevated serum ACTH levels, which was not the case in our patient; therefore, PCC was ruled out, and the patient was diagnosed with CS secondary to ACC. The most likely differential diagnosis for the clinical presentation in this patient with CS was panic attacks. Indeed, panic disorder is one of the most common psychiatric manifestations of CS (53%) [17]. It is characterized by the presence of recurrent episodes of panic attacks, defined by an abrupt surge of intense fear of losing control, “going crazy”, or dying, associated with 4 or more symptoms or physical signs, which include sweating, shaking, chills or heat sensations, dizziness, light-headedness, palpitations, tachycardia, chest pain or discomfort, shortness of breath, feeling of choking, nausea or abdominal distress, chills or heat sensations, paresthesias, and derealization or depersonalization. As it is the case in our patient, panic attacks can occur as often as several times a day, and without prodromes [18]. Other reported psychiatric manifestations in CS include depression (55–81%), anxiety (12%), mania or hypomania (3–27%), psychosis (8%), and confusion (1%) [17].

Similar to our case, there are a few reports of CS presenting with acute psychosis in the literature [19,20].

Conclusions

Adrenal tumors can have overlapping symptoms. It is essential to recognize psychiatric presentations of cortisol-producing ACC to achieve early diagnosis and prevent mortality and morbidity. A full diagnostic workup is warranted to rule out differential diagnoses for adrenal masses, with a combination of hormonal levels, imaging, and histology. ACC is a very aggressive malignancy and the overall prognosis is poor. However, some studies have shown improved survival in patients with early diagnosis and curative resections.

Figures

References:

1.. Sharma E, Dahal S, Sharma P, The characteristics and trends in adrenocortical carcinoma: A United States population based study: J Clin Med Res, 2018; 10(8); 636-40

2.. Koschker AC, Fassnacht M, Hahner S, Adrenocortical carcinoma – improving patient care by establishing new structures: Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes, 2006; 114(2); 45-51

3.. Else T, Kim AC, Sabolch A, Adrenocortical carcinoma: Endocr Rev, 2014; 35(2); 282-326

4.. Lacroix A, Feelders RA, Stratakis CA, Nieman LK, Cushing’s syndrome: Lancet, 2015; 386(9996); 913-27

5.. Le Tourneau C, Hoimes C, Zarwan C, Avelumab in patients with previously treated metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma: Phase 1b results from the JAVELIN solid tumor trial: J Immunother Cancer, 2018; 6(1); 111

6.. Ng L, Libertino JM, Adrenocortical carcinoma: Diagnosis, evaluation and treatment: J Urol, 2003; 169(1); 5-11

7.. Zekri W, Hammad M, Rashed WM, The outcome of childhood adrenocortical carcinoma in Egypt: A model from developing countries: Pediatr Hematol Oncol, 2020; 37(3); 198-210

8.. Chaudhry HS, Singh G, Cushing syndrome: StatPearls July 30, 2021, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing

9.. Katayama M, Nomura K, Ujihara M, Age-dependent decline in cortisol levels and clinical manifestations in patients with ACTH-independent Cushing’s syndrome: Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 1998; 49(3); 311-16

10.. Kiernan CM, Solórzano CC, Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: Diagnosis, genetics, and treatment: Surg Oncol Clin N Am, 2016; 25(1); 119-38

11.. Aniszewski JP, Young WF, Thompson GB, Cushing syndrome due to ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion: World J Surg, 2001; 25; 934-40

12.. Otsuka F, Miyoshi T, Murakami K, An extra-adrenal abdominal pheochromocytoma causing ectopic ACTH syndrome: Am J Hypertens, 2005; 18(10); 1364-68

13.. White A, Ray DW, Talbot A, Cushing’s syndrome due to phaeochromocytoma secreting the precursors of adrenocorticotropin: J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2000; 85; 4771-75

14.. Terzolo M, Ali A, Pia A, Bollito E, Cyclic Cushing’s syndrome due to ec-topic ACTH secretion by an adrenal pheochromocytoma: J Endocrinol Invest, 1994; 17; 869-74

15.. van Dam PS, van Gils A, Canninga-van Dijk MR, Sequential ACTH and catecholamine secretion in a phaeochromocytoma: Eur J Endocrinol, 2002; 147; 201-6

16.. Loh KC, Gupta R, Shlossberg AH, Spontaneous remission of ectopic Cushing’s syndrome due to pheochromocytoma: A case report: Eur J Endocrinol, 1996; 135; 440-43

17.. Lin TY, Hanna J, Ishak WW, Psychiatric symptoms in Cushing’s syndrome: A systematic review: Innov Clin Neurosci, 2020; 17(1–3); 30-35

18.. : DSM-5 Changes: Implications for Child Serious Emotional Disturbance June, 2016, Rockville (MD), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US)

19.. Hirsch D, Orr G, Kantarovich V, Cushing’s syndrome presenting as a schizophrenia-like psychotic state: Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci, 2000; 37(1); 46-50

20.. Wu Y, Chen J, Ma Y, Chen Z, Case report of Cushing’s syndrome with an acute psychotic presentation: Shanghai Arch Psychiatry, 2016; 28(3); 169-72

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Summary of the laboratory findings. Note that the increased renin level and the appropriately suppressed aldosterone level in the setting of excessive cortisol is suggestive of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), used by our patient for hypertension treatment.

Table 1.. Summary of the laboratory findings. Note that the increased renin level and the appropriately suppressed aldosterone level in the setting of excessive cortisol is suggestive of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), used by our patient for hypertension treatment. Table 1.. Summary of the laboratory findings. Note that the increased renin level and the appropriately suppressed aldosterone level in the setting of excessive cortisol is suggestive of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), used by our patient for hypertension treatment.

Table 1.. Summary of the laboratory findings. Note that the increased renin level and the appropriately suppressed aldosterone level in the setting of excessive cortisol is suggestive of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), used by our patient for hypertension treatment. In Press

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943118

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942826

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942770

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943214

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250