22 April 2023: Articles

Classical Presentation of Disseminated Blastomycosis in a 44-Year-Old Healthy Man 3 Months After Diagnosis of COVID-19

Challenging differential diagnosis, Rare disease

Diana Fan1ABDEF, Ali AhmadDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.938659

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e938659

Abstract

BACKGROUND: During the COVID-19 pandemic, the incidence of opportunistic infections, including fungal infections, has increased. Blastomycosis is caused by inhalation of an environmental fungus, Blastomyces dermatides, which is endemic in parts of the USA and Canada. This case report is of a 44-year-old man from the American Midwest who presented with disseminated blastomycosis infection 3 months following a diagnosis of COVID-19.

CASE REPORT: Our patient initially presented to an outpatient clinic with mild upper-respiratory symptoms. He tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 via polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Three months later, he presented to our emergency department due to some unresolved COVID-19 symptoms and the development of a widely disseminated, painful rash of 1-week duration. A positive Blastomyces urine enzyme immunoassay was the first indication of his diagnosis, which was followed by the identification of the pathogen via fungal culture from bronchoscopy samples and pathology from lung and skin biopsies. Given the evidence of dissemination, the patient was treated with an intravenous and oral antifungal regimen. He recovered well after completing treatment.

CONCLUSIONS: The immunocompetent status of patients should not exclude disseminated fungal infections as a differential diagnosis, despite the less frequent manifestations. This is especially important when there is a history of COVID-19, as this may predispose once-healthy individuals to more serious disease processes. This case supports the recent recommendations made by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for increased vigilance regarding fungal infections in patients with a history of COVID-19.

Keywords: Blastomycosis, COVID-19, invasive fungal infections, Male, Humans, Adult, Pandemics, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Blastomyces, Antifungal Agents, COVID-19 Testing

Background

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, co-infections with fungal pathogens have been documented in multiple studies around the world [1,2]. Primary infection with COVID-19 increases the risk for fungal infections due to its complex and multifactorial effect on the immune system and downstream metabolic and inflammatory responses of its victims [1,2]. In addition, patients receiving treatment for severe COVID-19 infection with systemic corticosteroids, monoclonal antibody therapy, and mechanical ventilation are known to be associated with an increased risk for super-imposed fungal infection [1–3]. Awareness of these risk factors and fungal co-infections in general, combined with strategies to minimize these risks, are essential to reducing the potentially deadly effects on those already suffering from primary COVID-19 infection [2,3].

Aspergillosis is the most common, with most studies describing COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) [2–4]. Following CAPA, COVID-19-associated mucormycosis (CAM) and invasive

Blastomycosis is caused by a group of dimorphic fungi that can infect both healthy and immunocompromised individuals [8]. This fungal infection was once known as Chicago disease because early cases were identified in the Chicago Metropolitan Area [8]. Currently, the geographic distribution has spread to encompass the entire Great Lakes region and river basins of the St. Lawrence, Ohio, and Mississippi Rivers [8]. In these regions, the incidence is less than 1 in 100 000, with the highest incidence in Wisconsin of 10–40 in 100 000 [9,10]. The fungus B dermatitidis, the most common causal agent, is found to inhabit moist soil [8,10]. This explains the high incidence of cases surrounding bodies of water in relation to disruptive human activities like construction and excavation [8]. Inhalation of fungal spores facilitates the conversion of this pathogen into its yeast form, invading the host through the lungs and potentially causing widespread disease due to the yeast’s thick wall providing some protection against phagocytosis [9,11]. Clinical manifestations vary broadly and can range from asymptomatic to acute respiratory distress syndrome and involvement of the skin, bone, and central nervous system [10,11]. Most patients presenting with disseminated fungal infections are immunocompromised, with 25–40% manifesting with extrapulmonary findings [11]. The criterion standard for diagnosis is growth of

This report is of a 44-year-old man from the American Midwest who presented with disseminated blastomycosis 3 months following a diagnosis of COVID-19.

Case Report

A 44-year-old man tested positive for COVID-19 by PCR at an outpatient center 3 months prior to presentation to our institution. His COVID symptoms consisted of a productive cough with some hemoptysis and loss of taste and smell but no oxygen requirements. A CBC performed at that time was largely unremarkable, including a normal white blood cell count of 9.4. A CT angiogram was also performed at the outside hospital, which showed a left upper-lobe mass that was indeterminate for malignancy versus rounded bacterial pneumonia. A short-interval follow-up chest CT was recommended. He reported that he was treated with a 14-day course of doxycycline with mild improvement of symptoms. He presented to us 3 months later with a persistent cough that never resolved from his COVID diagnosis. His cough had progressively worsened and was productive with yellow and blood-tinged sputum. He had associated unintentional weight loss of 11 kg over 3 months, decreased appetite, fatigue, and occasional night sweats, in addition to widespread, non-pruritic, tender papulopustular nodules that started appearing 1 week before presentation. The patient denied fever, chills, genitourinary, or gastrointestinal symptoms.

He denied tobacco and injection drug use, and he had no known history of STIs. He endorsed occasional cannabis and alcohol use. He had no recent travel history and had never been incarcerated or resided in homeless shelters. He worked at a desk job, and he had no exposure to wet wood or aerosolized dust from construction. He also denied performing activities such as hiking. Retrospectively, the patient was able to identify a possible exposure coinciding with the period of symptom onset; he was excavating soil in a field in southern Illinois several miles from the Mississippi River.

On exam, the patient appeared well with no acute distress. His lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally. Pink-purple, fluctuant nodules were widespread and scattered on his trunk, back, neck, and bilateral upper and lower extremities. Two older nodules were eroded with purulent drainage on his left lower leg (Figure 1A, 1B).

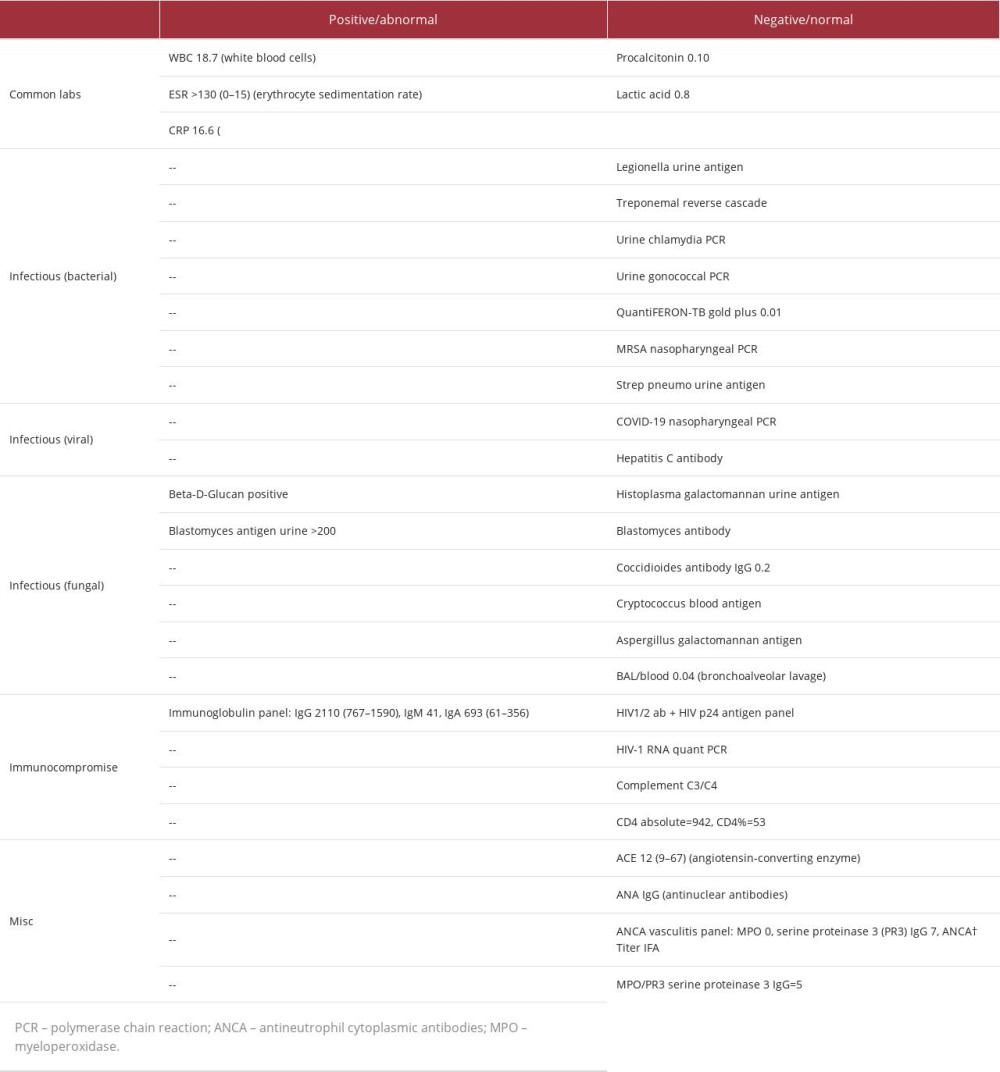

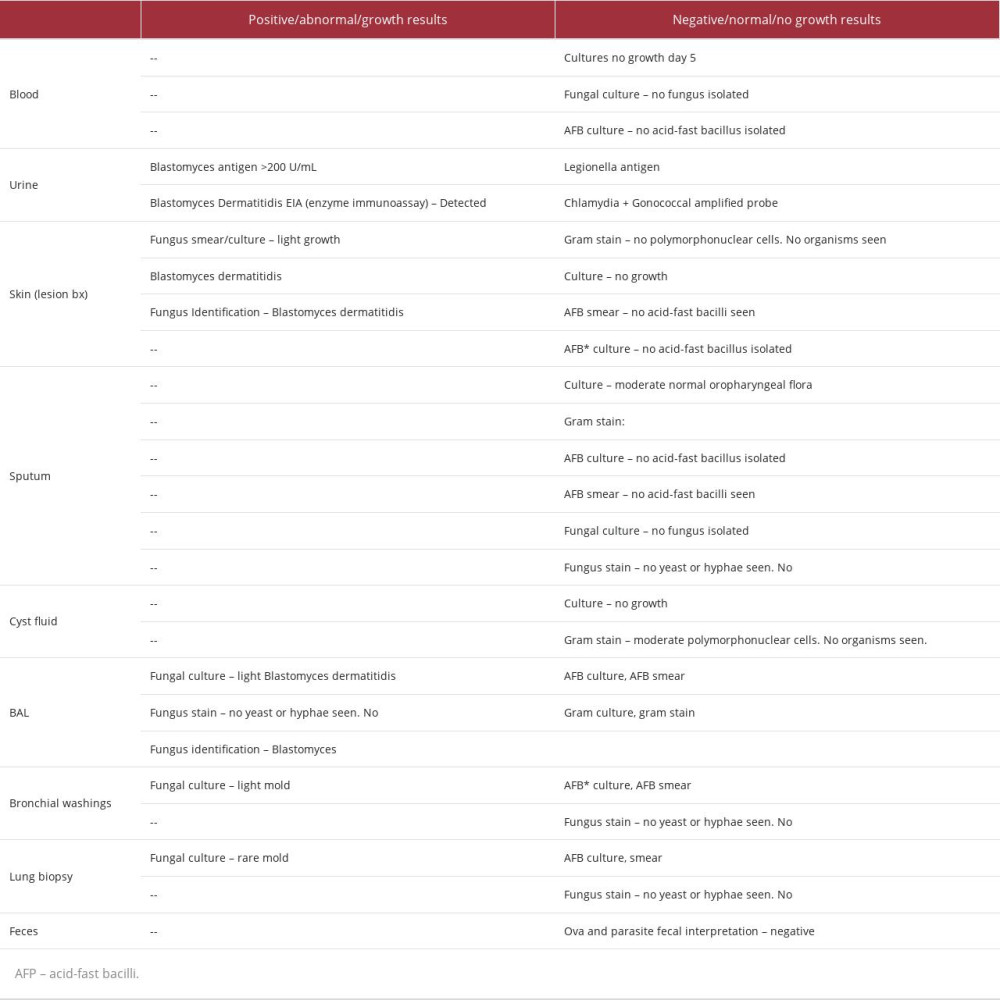

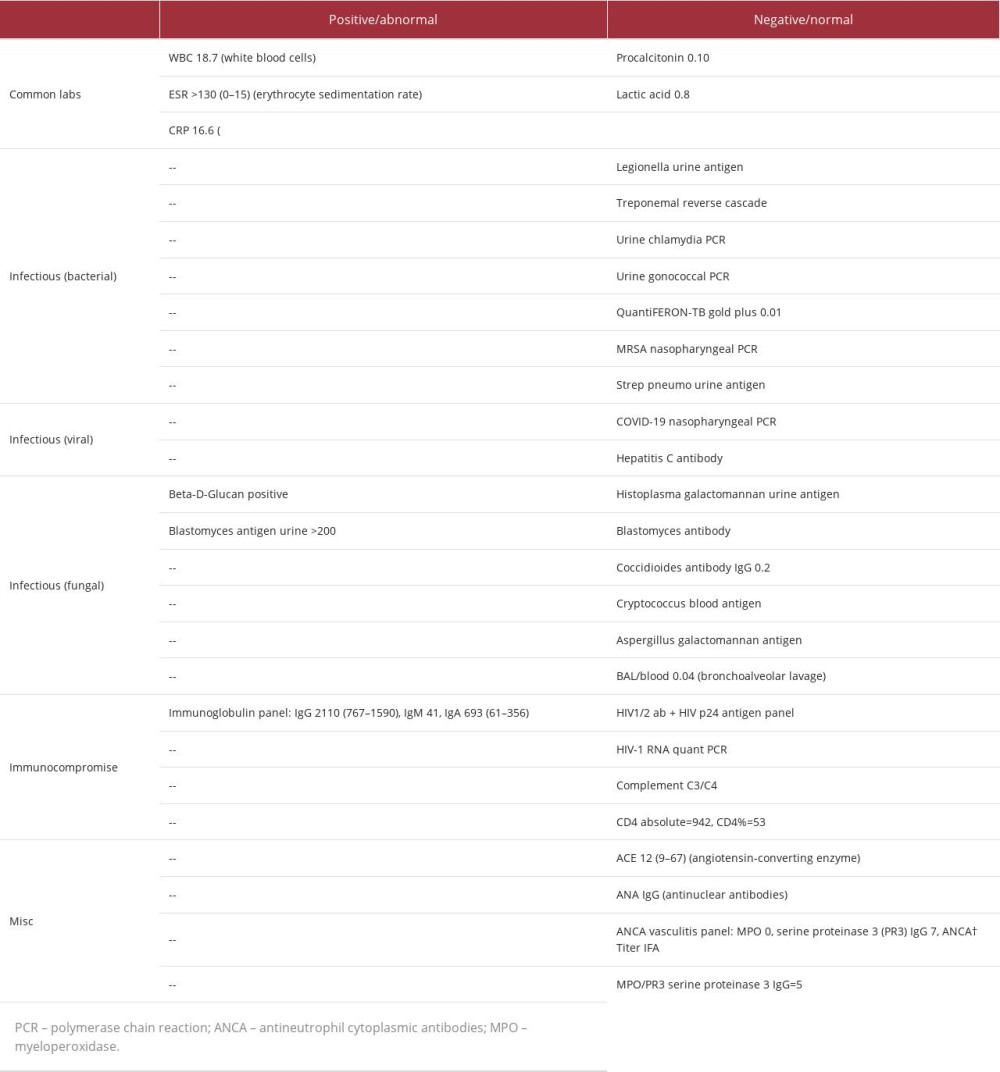

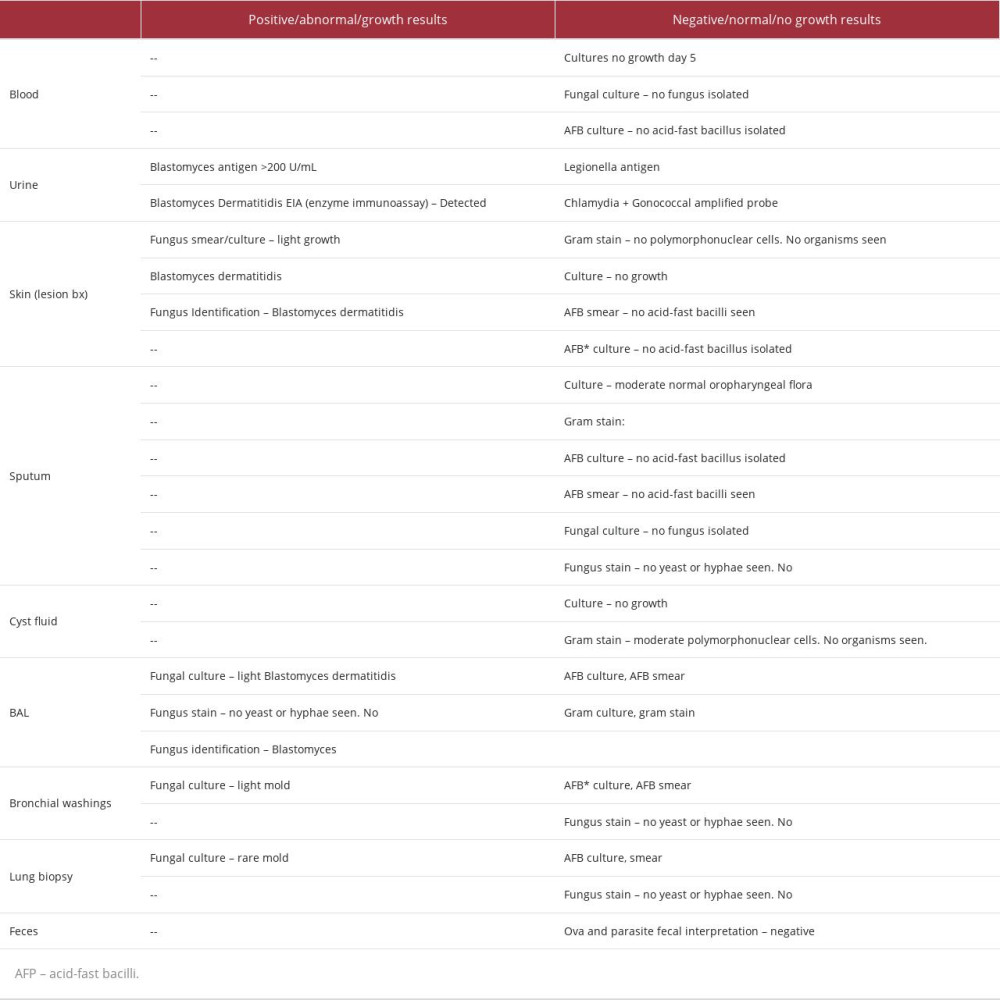

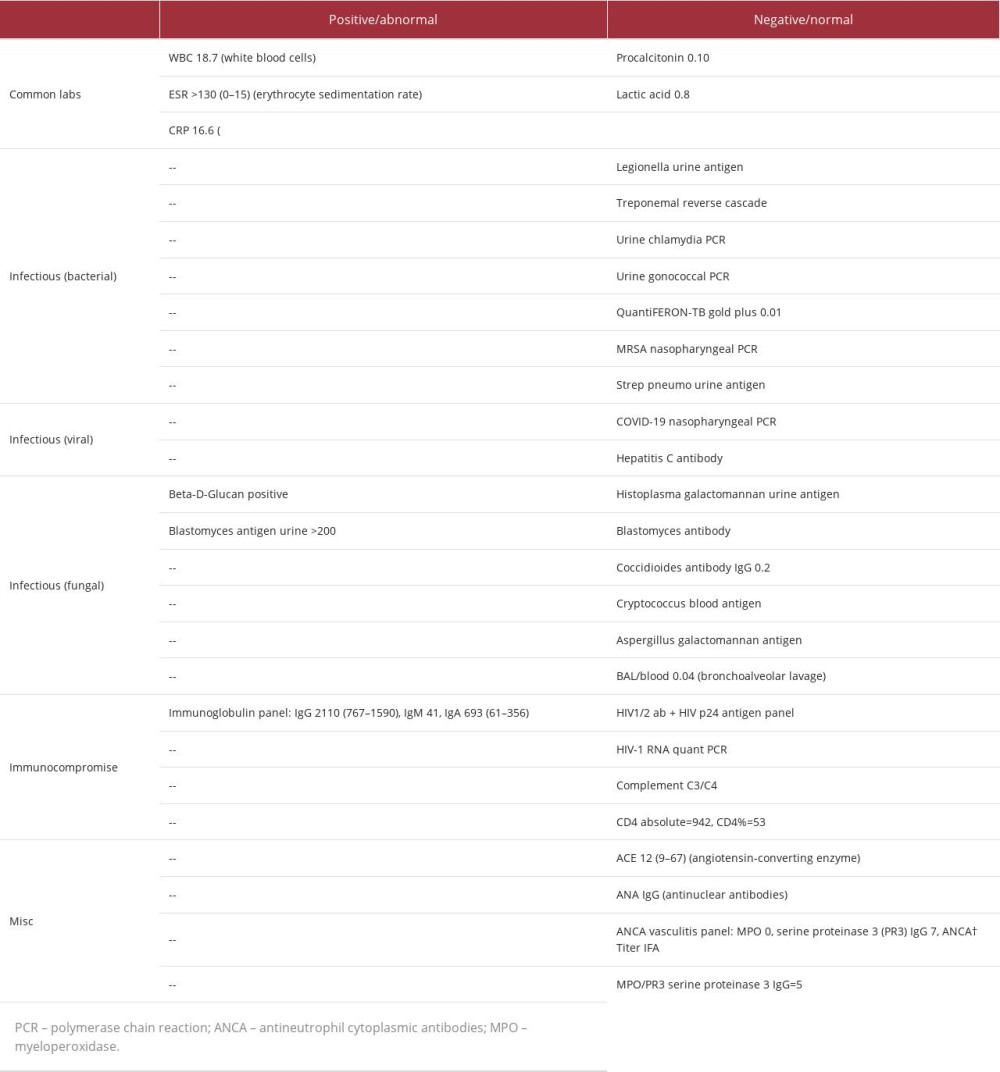

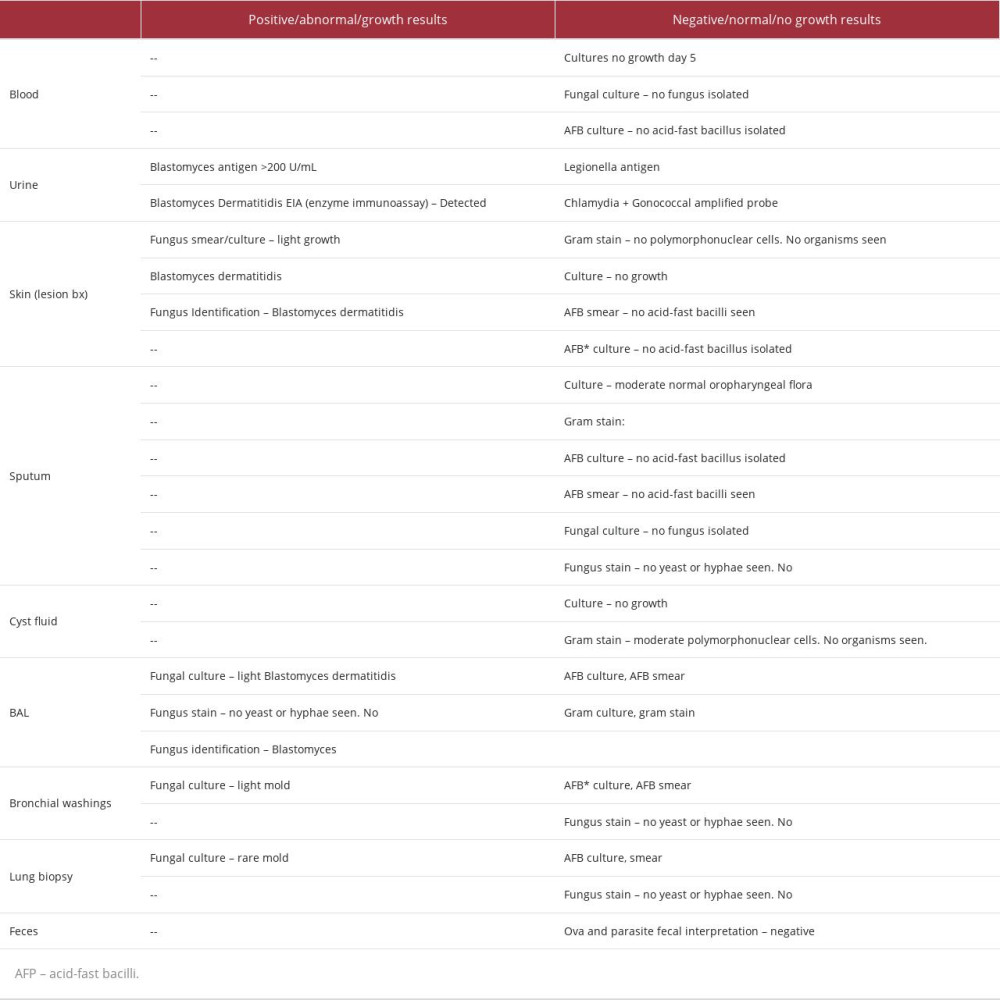

Initial infectious workup including blood cultures and a COVID PCR were negative, so a broadened workup for infectious and auto-immune causes was pursued. A full list of testing can be found in Tables 1 and 2. Blood serum testing was significant for leukocytosis of 18.7, elevated ESR >130 mm/hr, CRP 16.6 mg/dL, and positive Beta-D-Glucan. Serum Histoplasma, Coccidioides, Cryptococcus, Aspergillus, and Blastomycosis antigen testing was negative. Urine Histoplasma antigen was negative, while Blastomyces urine enzyme immunoassay was positive. Immunodeficiency studies such as HIV 1/2ab and p24 antigen panel were negative along with HIV RNA quantitative PCR <20. Complement C3/C4 and absolute CD4 counts were normal. Blood and sputum cultures were negative for bacteria, fungi, and acid-fast bacilli. Culture of cyst fluid from one of the skin lesions was also negative for any growth.

Chest X-rays showed left and right upper-lobe consolidative opacities with foci of cavitation, consistent with atelectasis and pneumonia (Figure 2). CT chest with contrast corroborated the consolidative opacities seen on X-ray, with the areas of cavitation concerning for multifocal necrotizing pneumonia (Figure 3A). CT of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast showed multifocal nodules within the subcutaneous fat with some extending to the surface of the skin, consistent with the nodules seen on the physical exam (Figure 3B). The appearance on CT suggested necrotic nodules or abscesses.

The patient was initially started on intravenous (IV) vancomycin, cefepime, and fluconazole given that the initial assessment was highly suggestive of necrotizing pneumonia. Other than a positive Beta-D-Glucan, persistent leukocytosis, and elevated inflammatory markers, initial laboratory evaluations for bacterial and fungal etiologies via antibody/antigen tests were all returning negative or normal for the first 2 days. All microbiology studies obtained via minimally invasive methods from blood, urine, sputum, and skin were either pending or showing no growth for acid-fast bacilli, gram stain, fungus, and yeast/hyphae.

Due to the concern for a disseminated infectious process affecting the lungs, a bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage was performed. The first confirmation of Blastomyces infection was through a positive urine antigen test, specifically

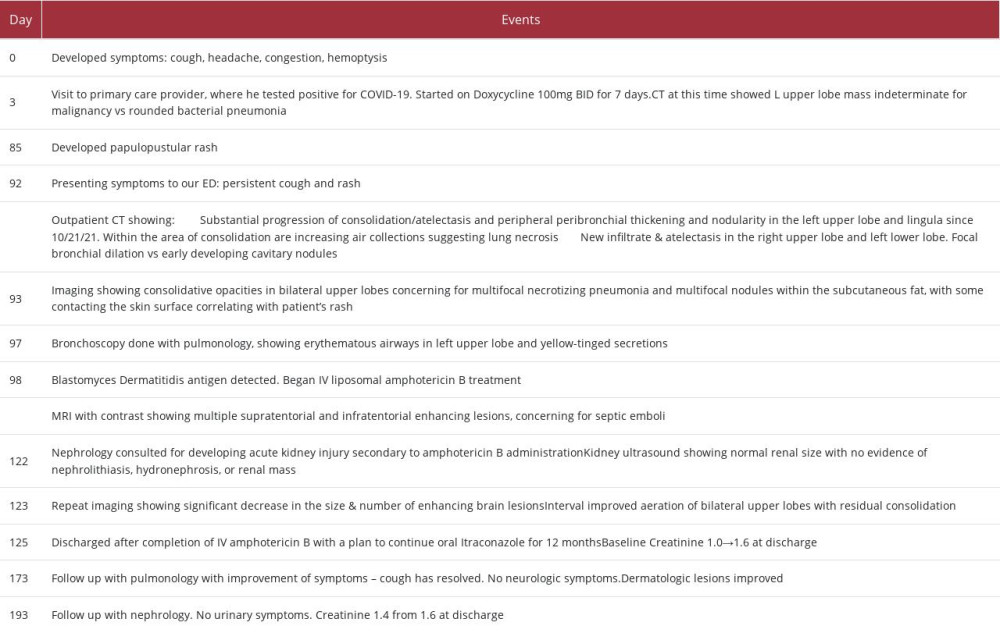

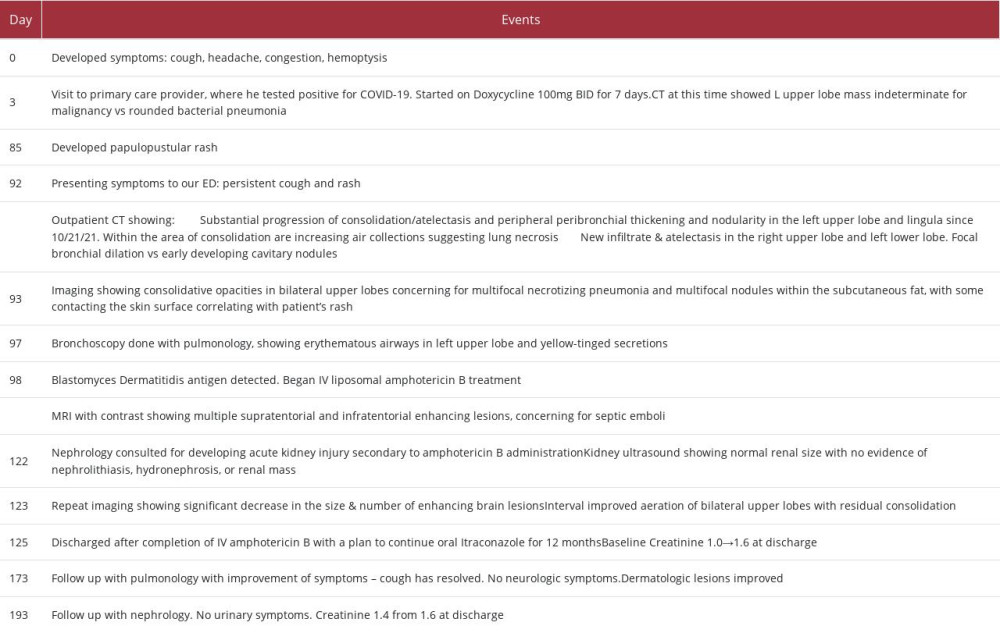

Because of the positive CNS findings on brain MRI performed shortly after diagnosis, the patient was continued on 4 weeks of amphotericin B IV daily. He developed a stage 1 acute kidney injury during this course, which improved but did not completely resolve with IV hydration. Repeat brain MRI and CT chest before the 4-week completion of amphotericin B showed improvement and a significant decrease in brain lesion size (Figure 6A, 6B). He was then transitioned to oral itraconazole with the plan to continue therapy for 1 year. At his 2-month follow-up appointment, the patient reported improvement in his previous symptoms. He was no longer coughing, and his dermatologic lesions had resolved with no sequelae. The patient’s entire course can be found in Table 3.

Discussion

This case report highlights the importance of identifying fungal pathogens early in patients with a history of COVID-19 given the deadly consequences of disseminated infection. The exact mechanisms by which the virus disrupts the patient’s immune system in a way that makes its victims more vulnerable to fungal colonization remains unclear. Although the majority of studies onCOVID-19-associated fungal infections found most robust associations with immune compromise, this should not exclude fungal infection from the differential in otherwise healthy patients [1,2,7]. We present a classical disseminated blastomycosis case to multiple organ systems in an immuno-competent patient with a notable history of mild COVID-19 infection with no steroid treatment.

During our patient’s initial ED course at the outside institution where he was diagnosed with COVID-19, the CT chest found an indeterminate left upper-lobe mass. Perhaps this may have been the initial manifestation of pulmonary blastomycosis. The patient then presented to us with progressive pulmonary symptoms that never completely resolved after his COVID-19 infection, and initial imaging showed necrotizing pneumonia that was presumed to be bacterial. However, with the onset of his skin manifestations, we pursued a workup for disseminated infections despite no apparent immunocompromise. The criterion standard for diagnosis of Blastomycosis is fungal culture, which can take weeks. Therefore, antigen detection by enzyme immunoassay is performed on serum or urine for more expeditious results and, therefore, prompt treatment [11]. Despite the lack of neurological symptoms, our patient showed evidence of CNS dissemination, and we were able to initiate treatment prior to any nervous system manifestations. After being informed of his diagnosis, the patient was able to retrospectively identify a single exposure event that was not recalled in the initial history-taking. We would therefore emphasize the importance of considering this rare manifestation of disseminated fungal disease in history-taking questions, even in immunocompetent patients. This is especially relevant in endemic regions at higher risk for exposure.

The COVID-19 epidemic has manifested in its victims as a primary respiratory infection with a wide range of symptom severity. In India, it has been associated in particular with Aspergillus and Mucorales. The true cause of this remains elusive. A systematic review of these risk factors included patients with severe COVID-19, ARDS, dysregulated immune function, and the use of immunomodulators [1]. It is suspected that the resulting cytokine storm and alveolar epithelial damage from severe COVID-19 infection creates a favorable environment for these molds to colonize from the nasal passages [1,12]. A similar process seems to occur following severe influenza infections. However, secondary mold and bacterial infections from influenza are due to damage to the large airway and direct suppression of NADPH oxidase [13]. COVID-19 appears to infect small-airway type 2 pneumocytes and ciliated cells. The association between COVID-19 and dimorphic fungi, such as blastomycosis, is even less clear. Two case reports show a possible association with disseminated histoplasmosis [14] and disseminated coccidioidomycosis [15]. However, both patients in these cases had other risk factors for infection; severe AIDS in the case of disseminated histoplasmosis and non-adherence to antifungals in the disseminated coccidioidomycosis case. In our case, the patient did not have any particular risk factors for fungal dissemination. His skin biopsy showed a low level of broad-based budding on GMS stain, which is possibly explained by the patient’s immunocompetent state. In addition, he was never treated with immunomodulators because he did not present with multi-organ failure due to COVID-19, unlike many other patients seen with co-infection of pulmonary aspergillosis and mucormycosis [4,7]. We describe the first association between recent mild COVID-19 infection and disseminated blastomycosis in an immunocompetent host. It is possible that COVID-19 infection itself increased our patient’s susceptibility to disseminated disease, but this would be speculative and require further study.

Conclusions

In our case, proper history-taking, history of COVID-19 infection, and geographic considerations were all taken into account to eventually arrive at the diagnosis that allowed us to treat before the development of serious or permanent disease manifestations. Fungal co-infections are classically seen in compromised hosts and those infected with COVID-19, but the apparent immunocompetent status of patients should not exclude disseminated fungal infections. This case supports the recent recommendations made by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for increased vigilance regarding fungal infections in patients with a history of COVID-19. The early recognition and inclusion of relatively rare, disseminated diseases are essential for the prompt identification and subsequent treatment of potentially deadly pathogens.

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. A full account of the laboratory results from a 44-year-old man with a diagnosis of blastomycosis. Common laboratory tests, bacterial, viral, and fungal infectious workup, and immune studies are reported. Results are reported as either positive/ abnormal or negative/normal. Numerical values are reported when applicable with the normal ranges in parenthesis. Table 2.. A full account of the microbiology results from a 44-year-old man with a diagnosis of blastomycosis. Results are reported as either positive/abnormal/growth results or negative/normal/no growth results. Identification of microorganisms in growth results is reported when applicable.

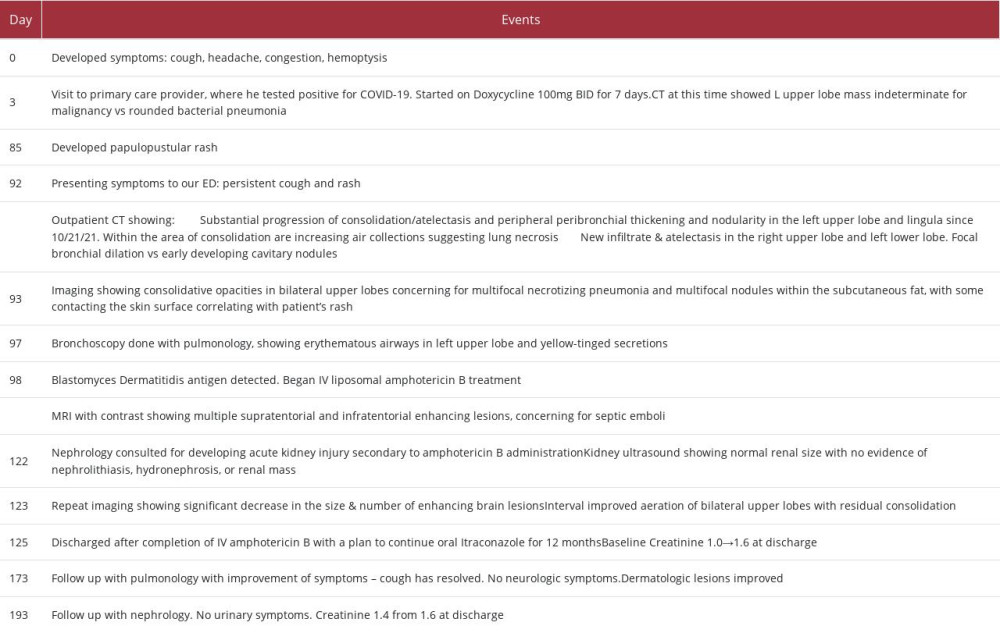

Table 2.. A full account of the microbiology results from a 44-year-old man with a diagnosis of blastomycosis. Results are reported as either positive/abnormal/growth results or negative/normal/no growth results. Identification of microorganisms in growth results is reported when applicable. Table 3.. A comprehensive account of events from the entire disease course of a 44-year-old male with a diagnosis of blastomycosis, as described in this case report. Day 0 is marked as symptom onset. Following events are listed in chronological order according to days since symptom onset.

Table 3.. A comprehensive account of events from the entire disease course of a 44-year-old male with a diagnosis of blastomycosis, as described in this case report. Day 0 is marked as symptom onset. Following events are listed in chronological order according to days since symptom onset.

References:

1.. Soni S, Namdeo Pudake R, Jain U, Chauhan N, A systematic review on SARSCoV-2-associated fungal coinfections: J Med Virol, 2022; 94(1); 99-109

2.. Hoenigl M, Seidel D, Sprute R, COVID-19-associated fungal infections: Nat Microbiol, 2022; 7(8); 1127-40

3.. , Fungal Diseases and COVID-19 March 2, 2022 Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/covid-fungal.html

4.. Lai CC, Yu WL, COVID-19 associated with pulmonary aspergillosis: A literature review: J Microbiol Immunol Infect, 2021; 54(1); 46-53

5.. Messina FA, Marin E, Caceres DH, Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a patient with disseminated histoplasmosis and HIV-A case report from argentina and literature review: J Fungi (Basel), 2020; 6(4); 275

6.. Krauth DS, Jamros CM, Rivard SC, Accelerated progression of disseminated coccidioidomycosis following SARS-CoV-2 infection: A case report: Mil Med, 2021; 186(11–12); 1254-56

7.. Al-Tawfiq JA, Alhumaid S, Alshukairi AN, COVID-19 and mucormycosis superinfection: the perfect storm: Infection, 2021; 49(5); 833-53

8.. Mazi PB, Rauseo AM, Spec A, Blastomycosis: Infect Dis Clin North Am, 2021; 35(2); 515-30

9.. Miceli A, Krishnamurthy K, Blastomycosis: StatPearls [Internet] Aug 21, 2022, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing 2022 Jan. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441987/

10.. , Fungal diseases: Blastomycosis February 9, 2022 Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/blastomycosis/index.html

11.. McBride JA, Gauthier GM, Klein BS, Clinical manifestations and treatment of blastomycosis: Clin Chest Med, 2017; 38(3); 435-49

12.. Tabassum T, Araf Y, Moin AT, Rahaman TI, Hosen MJ, COVID-19-associated-mucormycosis: Possible role of free iron uptake and immunosuppression: Mol Biol Rep, 2022; 49(1); 747-54

13.. Verweij PE, Rijnders BJA, Brüggemann RJM, Review of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis in ICU patients and proposal for a case definition: an expert opinion: Intensive Care Med, 2020; 46(8); 1524-35

14.. Bertolini M, Mutti MF, Barletta JA, COVID-19 associated with AIDS-related disseminated histoplasmosis: A case report: Int J STD AIDS, 2020; 31(12); 1222-24

15.. Shah AS, Heidari A, Civelli VF, The coincidence of 2 epidemics, coccidioidomycosis and SARS-CoV-2: A case report: J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep, 2020; 8; 2324709620930540

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. A full account of the laboratory results from a 44-year-old man with a diagnosis of blastomycosis. Common laboratory tests, bacterial, viral, and fungal infectious workup, and immune studies are reported. Results are reported as either positive/ abnormal or negative/normal. Numerical values are reported when applicable with the normal ranges in parenthesis.

Table 1.. A full account of the laboratory results from a 44-year-old man with a diagnosis of blastomycosis. Common laboratory tests, bacterial, viral, and fungal infectious workup, and immune studies are reported. Results are reported as either positive/ abnormal or negative/normal. Numerical values are reported when applicable with the normal ranges in parenthesis. Table 2.. A full account of the microbiology results from a 44-year-old man with a diagnosis of blastomycosis. Results are reported as either positive/abnormal/growth results or negative/normal/no growth results. Identification of microorganisms in growth results is reported when applicable.

Table 2.. A full account of the microbiology results from a 44-year-old man with a diagnosis of blastomycosis. Results are reported as either positive/abnormal/growth results or negative/normal/no growth results. Identification of microorganisms in growth results is reported when applicable. Table 3.. A comprehensive account of events from the entire disease course of a 44-year-old male with a diagnosis of blastomycosis, as described in this case report. Day 0 is marked as symptom onset. Following events are listed in chronological order according to days since symptom onset.

Table 3.. A comprehensive account of events from the entire disease course of a 44-year-old male with a diagnosis of blastomycosis, as described in this case report. Day 0 is marked as symptom onset. Following events are listed in chronological order according to days since symptom onset. Table 1.. A full account of the laboratory results from a 44-year-old man with a diagnosis of blastomycosis. Common laboratory tests, bacterial, viral, and fungal infectious workup, and immune studies are reported. Results are reported as either positive/ abnormal or negative/normal. Numerical values are reported when applicable with the normal ranges in parenthesis.

Table 1.. A full account of the laboratory results from a 44-year-old man with a diagnosis of blastomycosis. Common laboratory tests, bacterial, viral, and fungal infectious workup, and immune studies are reported. Results are reported as either positive/ abnormal or negative/normal. Numerical values are reported when applicable with the normal ranges in parenthesis. Table 2.. A full account of the microbiology results from a 44-year-old man with a diagnosis of blastomycosis. Results are reported as either positive/abnormal/growth results or negative/normal/no growth results. Identification of microorganisms in growth results is reported when applicable.

Table 2.. A full account of the microbiology results from a 44-year-old man with a diagnosis of blastomycosis. Results are reported as either positive/abnormal/growth results or negative/normal/no growth results. Identification of microorganisms in growth results is reported when applicable. Table 3.. A comprehensive account of events from the entire disease course of a 44-year-old male with a diagnosis of blastomycosis, as described in this case report. Day 0 is marked as symptom onset. Following events are listed in chronological order according to days since symptom onset.

Table 3.. A comprehensive account of events from the entire disease course of a 44-year-old male with a diagnosis of blastomycosis, as described in this case report. Day 0 is marked as symptom onset. Following events are listed in chronological order according to days since symptom onset. In Press

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943118

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942826

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942770

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943214

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250