07 March 2023: Articles

AIDS-Related Kaposi Sarcoma Associated with Steroid-Unresponsive Periorbital Lymphedema that Responded to Chemotherapy

Challenging differential diagnosis, Diagnostic / therapeutic accidents, Unusual setting of medical care, Rare disease, Educational Purpose (only if useful for a systematic review or synthesis)

Yuhao Zeng1ABCDEF, Rahul Prasad1ABCDEF, Rachel D. King1BDE, Rajshri Joshi1E, Jason Lane2BDE, Sterling Shriber1E, Faris Shweikeh1E, Yani Zhang3ADEF*DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.938801

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e938801

Abstract

BACKGROUND: As an AIDS-defining illness, the neoplasm Kaposi sarcoma (KS) classically presents as cutaneous lesions that are often associated with periorbital edema. This association with KS is important because it frequently leads to the misuse of steroids in HIV-infected patients. This report presents 2 cases of AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma (AIDS-KS) associated with severe steroid-unresponsive periorbital lymphedema that responded to chemotherapy.

CASE REPORT: Case 1: A 30-year-old African-American man with KS-related periorbital edema suffered progression after receiving multiple corticosteroids for a presumed hypersensitivity reaction. After multiple hospitalizations, the patient’s KS had disseminated, and he eventually opted for hospice. Case 2: A 29-year-old White male with recurrent facial edema had been repeatedly treated with corticosteroids for impending anaphylaxis reactions. He had multiple admissions with similar presentations, and it was found that his KS had progressed. After receiving chemotherapy, his facial edema has not recurred.

CONCLUSIONS: The failure to recognize periorbital edema as tumor-associated edema has direct consequences for the management of AIDS-KS. In addition to a delay in administering chemotherapy, the mischaracterization of periorbital edema as a hypersensitivity/allergic reaction often prompts the use of corticosteroids, potentially exacerbating the underlying AIDS-KS. Despite the current evidence, clinicians continue to order steroids in advanced AIDS-KS patients presenting with periorbital edema. Although that management is started with the best intentions and done with concerns for airway compromise, this anchoring bias could lead to devastating consequences and a rather poor prognosis.

Keywords: AIDS-Related Kaposi Sarcoma, lymphedema, Humans, Male, Adult, Sarcoma, Kaposi, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, Steroids, angioedema, Blepharoptosis, Cellulitis

Background

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)-driven, low-grade, angioproliferative neoplasm [1]. As an AIDS-defining illness, KS classically presents as cutaneous lesions that are often indurated, non-pruritic, painless, elliptical, ranging in size from millimeters to centimeters in width, and varying in color from beige to brown. Lesions appear most frequently on the lower extremities, face, oral mucosa, and genitalia. However, facial lesions have only been observed in AIDS-associated KS (AIDS-KS) [2]. After the introduction of potent antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the mid-1990s, the KS incidence rate drastically dropped, from 9.3% in 1990 to 1.1% in 2014 [3]. In the non-AIDS solid organ transplantation population, an annual incidence of 12.4 per million people from 1987–2014 was reported, largely due to treatment with immunosuppressants. No specific medication association has been identified [4]. However, a large number of KS cases are still present as a result of improved survival, and the number of people living with AIDS has more than doubled in the United States [5].

Lymphedema, particularly in the face, was first reported by Zidar [6] in 1995. The edema may be disproportionate to the tumor’s extent and can easily masquerade as angioedema, which is of concern to clinicians and often results in urgent corticosteroid use.

Here, we describe a case series of periorbital lymphedema caused by facial involvement of AIDS-KS. Intravenous corticosteroids were received by 2 young men on many occasions, eventually precipitating the progression of the disease. The hospitalization course for each patient is summarized in Figure 1. We review pathogenesis, clinical features, outcomes, and management related to periorbital edema in patients with AIDS-KS.

Case Reports

CASE 1:

A 30-year-old African-American cachectic male was hospitalized in April 2021 with surgical management for the right tonsillar region. At that time, he was diagnosed with AIDS, with a CD4 count of 4 cells/mm3 and was also noted to have multiple violaceous skin patches on his upper extremities that were suspicious for KS. After being discharged, he followed up with an out-patient infectious disease specialist. He was found to have oral candidiasis and multiple evolving violaceous, indurated lesions on his face, trunk, and lower extremities. He was immediately started on bictegravir, emtricitabine, tenofovir alafenamide, and fluconazole. Three days later, he presented to the emergency department (ED) with worsened facial and periorbital edema. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed diffuse soft tissue swelling with skin thickening. His symptoms improved slightly with the administration of epinephrine and methylprednisolone. His ART regimen was discontinued due to the presumption of an allergic reaction, and he was discharged with a prednisone taper. He later had 3 additional ED evaluations over the next 2 months for recurrent facial swelling, which was managed as prior with glucocorticoids. Additionally, he was given a 14-day course of doxycycline and a referral to allergy specialists.

In July 2021 (163 days after the first documented skin lesions), the patient presented to the ED again with recurring left facial swelling and a new onset of melanotic stool associated with back and abdominal pain for the previous 2 days. Physical examination showed mild fever (38.4°C) and diffuse violaceous skin nodules on the face, legs, arms, and gingiva. Oral thrush was also noted. CD4 count was 12 cells/mm3, and viral load was 82,000 copies/mL. ART with a new regimen of doravirine and darunavir-cobicistat was initiated. Concurrent treatments included intravenous vancomycin for methicillin-resistant

The patient had a prolonged and complicated hospitalization course. On hospital day 3, the patient showed worsening facial swelling that was more prominent on the left side (Figure 2). MRI findings on day 5 post-admission are described in Figure 3. Disseminated KS was suspected as a unifying diagnosis for the patient’s diverse symptoms. Visceral involvement was confirmed by esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy. Biopsy-confirmed KS was found in the duodenum, gastric cardia, stomach, and rectum. Lumbar spine CT was conducted due to worsening back pain, and it revealed a 1.2 x 1.6 cm lytic lesion in the right L1 vertebra transverse process, with an extending fluid collection. Image-guided bone biopsy demonstrated a spindle cell neoplasm positive by immunohistochemical staining for ERG and CD31 (both endothelial markers) as well as HHV-8, consistent with the diagnosis of KS (Figure 4). The final treatment plan was to continue ART therapy and commence systemic liposomal doxorubicin after the resolution of underlying bacteremia. Unfortunately, the patient failed to follow up after 2 subsequent hospitalizations for suicidal ideation. He presented to the ED with diffuse body pain again, 217 days after his first documented skin lesions, and at that time opted for hospice care.

CASE 2:

A 29-year-old White male presented to the ED with severe right facial swelling that started the evening before with the development of visual impairment. This was accompanied by a sensation of throat closure and vocal hoarseness with non-tender, purple skin lesions on his nose and sternum for the past month. He reported recent sexual activities with multiple male partners without protection. He disclosed a previous, milder episode of facial swelling 3 weeks prior, accompanied by sore throat and odynophagia. At that time, he was discharged from the ED with a course of clindamycin and dexamethasone because right-sided tonsillar exudates were noted and a right multiloculated peritonsillar abscess was revealed on CT.

During this hospitalization, vital signs were unremarkable except for slight tachycardia (heart rate, 102 beats/min). Physical examination showed diffuse facial and periorbital edema with raccoon’s sign, but no tongue or lip involvement, and no apparent tonsillar enlargement. A complete skin examination revealed approximately 6 violaceous cutaneous lesions on the nose, chest, back, and legs (Figure 5). A few lesions were also observed in the oropharynx, without evidence of ulceration. The complete blood count showed thrombocytopenia, and the comprehensive metabolic panel was unremarkable. His CT findings upon ED arrival are described in Figure 6. He was administered an empiric dose of intramuscular epinephrine, IV methylprednisolone, diphenhydramine, and famotidine. He was subsequently admitted to the regular floor for angioedema.

Since the facial edema had only minimally improved, and vocal hoarseness had persisted, glucocorticoid therapy was continued until hospital day 6. In the meantime, an HIV-1 screen returned positive, with a CD4 count of 83 cells/mm3 (5%) and viral load of 1,920,000 copies/mL. Further CT findings showed bilateral axillary (greater on the right) and mesenteric adenopathy. A core biopsy of the right axilla is demonstrated in Figure 7. These findings are consistent with the diagnosis of KS. The patient was clinically diagnosed with AIDS-KS, with plans for topical alitretinoin. The facial edema was determined to be idiopathic non-histaminergic acquired angioedema related to HIV infection. The patient started bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide at discharge (day 27 from index presentation). Additionally, he was prescribed subcutaneous epinephrine and prednisone in the case of recurrent symptoms.

The patient had 2 additional admissions for facial swelling over the next month. The first occurred on day 35 of his first episode. He received additional high-dose glucocorticoids, which again improved his symptoms. A CT scan of the neck showed a residual right peritonsillar abscess, similar to the prior one. The facial swelling returned 2 days later. It was now accompanied by jaundice, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, mucosal discharge per rectum, and markedly elevated liver function tests. The patient again received high-dose glucocorticoids on admission for his facial swelling. His CD4 count was now 314 cells/mm3, and the viral load was 1,530 copies/mL. ART and prophylactic trim-ethoprim/sulfamethoxazole were withheld on day 49 for rising total bilirubin. An abdominal CT scan showed new findings of gallbladder wall thickening and mild irregular rectal wall thickening, in addition to unchanged mesenteric lymphadenopathy. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed multiple vascular liver lesions suspicious for metastasis. Multiple bony lesions were also noted. Flexible sigmoidoscopy showed large vascular lesions in the rectum, which were consistent with KS.

The final treatment plan was to resume ART, continue liposomal doxorubicin, and continue valganciclovir for a total of 21 days. Upon followup 6 weeks later, his facial swelling was much improved.

Discussion

We wish to highlight a few aspects of these cases: 1) Periorbital edema in AIDS-KS is a clinical phenomenon that warrants recognition in guiding clinical management. 2) Judicious corticosteroid use is recommended in advanced AIDS-KS patients presenting with periorbital edema. 3) Timely diagnosis and prompt use of systemic chemotherapy and/or localized radio-therapy is the key to a good prognosis.

Although lymphedema seems to occur in all forms of KS, the exact mechanism is not clear. One theory is that KS cells occlude the flow of lymph. Current evidence strongly favors a lymphatic endothelium derivation of KS [7]. Corticosteroid therapy has been a well-known exacerbating factor for preexisting KS in the HIV-infected population. Reports of an accumulating number cases have observed that there is increased mortality with the use of corticosteroids in AIDS-KS individuals, and several mechanisms have been proposed to account for these observations. In vitro, corticosteroids induce AIDS-KS-derived spindle cell lines to proliferate by downregulating activation of autocrine TGF-beta, and the proliferative effects are dose-dependent [8]. Also, hydrocortisone acts directly on HHV-8-positive BCBL-1 cells (human B cell lymphoma cell line) to activate the lytic cycle of HHV-8, which may contribute to the development of KS in organ transplantation patients [9].

In contrast to most malignancies, a non-Tumor, Node, Metastases (TNM) staging system is used to stratify and determine the prognosis of KS [10]. The AIDS Clinical Trial Group proposed and later validated a novel staging system known as Tumor, Immune System, Systemic Illness (TIS) staging [11]. T1 identification can be achieved by physical exam through recognition of tumor-associated edema or ulceration. As such, any KS patients with periorbital edema will be assigned to the poor prognostic category. The earlier proposed hypothesis was that periorbital edema is a sign that heralds impending mortality [6,12]. This is consistent with the TIS staging system, and has been supported by survival analysis data from 144 patients from the Swiss HIV cohort study [13].

Combining ART with systemic chemotherapy, such as liposomal anthracyclines, is typically reserved for patients with classification stage T1 features [14–18]. Among advanced AIDS patients, opportunistic infections are often present. A “cytokine storm” can follow ART initiation and further increase the risk for mortality [19,20]. Corticosteroid therapy may be perceived as an intuitive solution to addressing the increased cytokine release following ART initiation. Surprisingly, however, corticosteroid use itself has been notably shown to be a risk factor for developing immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), as well as being an independent mortality risk factor in AIDS-KS [8,20].

Clinical data are limited on adjunctive corticosteroid therapy for severe IRIS without KS. A plausible indication for corticosteroid use is to treat patients with symptomatic increased intracranial pressure related to IRIS. This is based on case reports and extrapolation from other disease processes. Although data suggest that systemic chemotherapy is beneficial for IRIS [21], if other immunosuppressants are available, they may be beneficial for reducing the mortality from KS or KS with IRIS, possibly inhibiting KS growth by blocking cytokine-induced KS proliferation. More high-quality data from clinical trials are needed to further answer those questions.

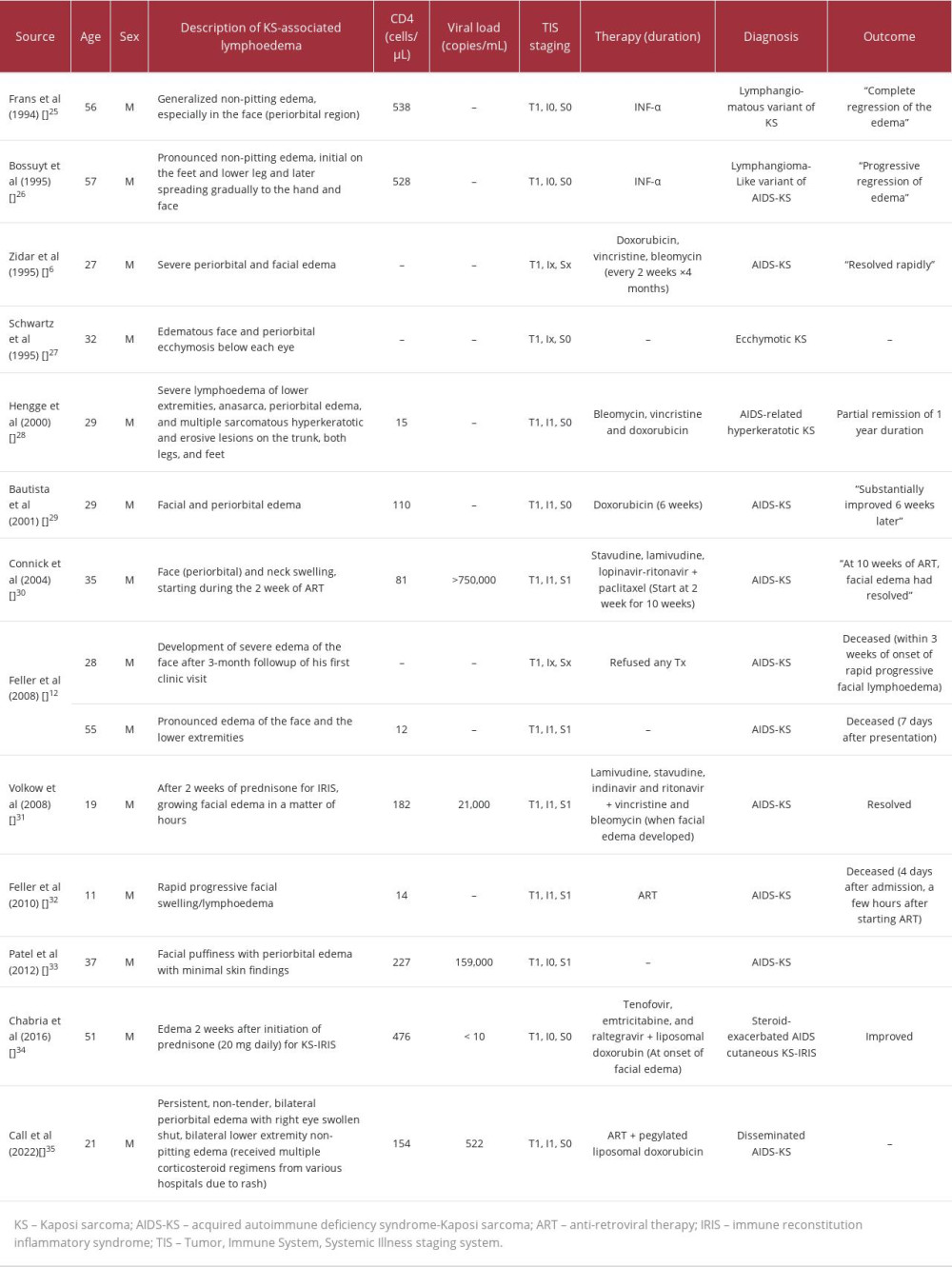

To assess the potential significance of AIDS-KS-associated facial edema, a literature review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [22]. The following search terms were used: “Kaposi sarcoma,” “facial,” “periorbital,” “edema,” ”swelling,” and “lymphedema.” A PubMed search of case reports and case series was done to identify relevant English literature from 1/1/1994 to 9/30/2022. Articles from prior to 1994 were excluded as ART was not yet the standard of care. The references of retrieved articles were also reviewed to identify additional sources. Data were obtained as available from each publication regarding demographic information, viral loads, CD4 cell counts, AIDS-KS severity, treatment regimen, and clinical progression. TIS staging was extrapolated from the published clinical and laboratory data provided. Using this method, we identified 13 publications that described 14 cases of AIDS-KS with periorbital edema (Table 1).

More than 70% of the patients were between 11 and 37 years of age, and all patients were male. Four cases developed facial swelling during the treatment. (Three of these received corticosteroids). Four of the 10 (40.0%) with reported CD4 counts were staged as immune-high risk (I1). Seven of the 13 (53.8%) reported systemic illness status. In terms of management, 7 received systemic chemotherapy with significant resolution of facial edema, 4 continued prior ART, 3 initiated ART after the presentation, and 2 died prior to any therapy. Of note, the 3 who did not receive systemic chemotherapy died during the same admission as their initial presentation.

Periorbital edema also has been proposed as a sign of serious complication, suggesting disseminated disease and indicating the use of systemic chemotherapy instead of only localized radiotherapy [14–16]. In both of our cases, and 2 previously reported cases, the presence of periorbital edema was initially managed with corticosteroids in an attempt to ameliorate symptoms. While we observed a reduction in edema in our 2 patients, in all 4 cases, KS symptoms were exacerbated. The presumption of a drug reaction in our case 2 also prompted the avoidable discontinuation of ART. Periorbital edema is a clinically challenging symptom due to a broad range of associated diagnoses. Causes of periorbital edema have been grouped into 4 categories: infectious, non-infectious (inflammatory/tumor), postsurgical/trauma, and medications [23]. Several conditions causing periorbital edema can superficially mimic angioedema; so-called “pseudoangioedemas” [24]. The failure to recognize periorbital edema as tumor-associated edema has direct consequences for the management of AIDS-KS. In addition to a delay in administering chemotherapy, the mischaracterization of periorbital edema as a hypersensitivity/allergic reaction often prompts the use of corticosteroids, potentially exacerbating the underlying AIDS-KS.

Conclusions

These 2 reports have highlighted that lymphedema, including orbital lymphedema, can be associated with AIDS-KS and might not respond to steroids, but should respond to chemo-therapy for KS. Chemotherapy is the key to better outcomes.

Figures

References:

1.. Gao SJ, Kingsley L, Hoover DR, Seroconversion to antibodies against Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-related latent nuclear antigens before the development of Kaposi’s sarcoma: N Engl J Med, 1996; 335(4); 233-41

2.. Laresche C, Fournier E, Dupond AS, Kaposi’s sarcoma: A population-based cancer registry descriptive study of 57 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1977 and 2009: Int J Dermatol, 2014; 53(12); e549-54

3.. Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Miller D: SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2014, National Cancer Institute, 2017, Bethesda, MD, SEER web site Available from:https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/

4.. Cahoon EK, Linet MS, Clarke CA, Risk of Kaposi sarcoma after solid organ transplantation in the United States: Int J Cancer, 2018; 143(11); 2741-48

5.. Yarchoan R, Uldrick TS, HIV-associated cancers and related diseases: N Engl J Med, 2018; 378(11); 1029-41

6.. Zidar BL, Images in clinical medicine. Periorbital edema in Kaposi’s sarcoma: N Engl J Med, 1995; 332(18); 1204

7.. Beckstead JH, Wood GS, Fletcher V, Evidence for the origin of Kaposi’s sarcoma from lymphatic endothelium: Am J Pathol, 1985; 119(2); 294-300

8.. Cai J, Zheng T, Lotz M, Glucocorticoids induce Kaposi’s sarcoma cell proliferation through the regulation of transforming growth factor-beta: Blood, 1997; 89(5); 1491-500

9.. Hudnall SD, Rady PL, Tyring SK, Fish JC, Hydrocortisone activation of human herpesvirus 8 viral DNA replication and gene expression in vitro: Transplantation, 1999; 67(5); 648-52

10.. Nasti G, Talamini R, Antinori A, AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma: Evaluation of potential new prognostic factors and assessment of the AIDS Clinical Trial Group Staging System in the Haart Era – the Italian Cooperative Group on AIDS and Tumors and the Italian Cohort of Patients Naive From Antiretrovirals: J Clin Oncol, 2003; 21(15); 2876-82

11.. Krown SE, Metroka C, Wernz JC, Kaposi’s sarcoma in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome: A proposal for uniform evaluation, response, and staging criteria. AIDS Clinical Trials Group Oncology Committee: J Clin Oncol, 1989; 7(9); 1201-7

12.. Feller L, Masipa J, Wood N, The prognostic significance of facial lymph-oedema in HIV-seropositive subjects with Kaposi sarcoma: AIDS Res Ther, 2008; 5; 2

13.. El Amari EB, Toutous-Trellu L, Gayet-Ageron A, Predicting the evolution of Kaposi sarcoma, in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: Aids, 2008; 22(9); 1019-28

14.. Dezube BJ, Pantanowitz L, Aboulafia DM, Management of AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma: Advances in target discovery and treatment: AIDS Read, 2004; 14(5); 236-38

15.. Gbabe OF, Okwundu CI, Dedicoat M, Freeman EE, Treatment of severe or progressive Kaposi’s sarcoma in HIV-infected adults: Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2014; 8(8); CD003256

16.. Krown SE, Highly active antiretroviral therapy in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma: Implications for the design of therapeutic trials in patients with advanced, symptomatic Kaposi’s sarcoma: J Clin Oncol, 2004; 22(3); 399-402

17.. Bower M, Collins S, Cottrill C, British HIV Association guidelines for HIV-associated malignancies 2008: HIV Med, 2008; 9(6); 336-88

18.. Gorsky M, Epstein JB, A case series of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients with initial neoplastic diagnoses of intraoral Kaposi’s sarcoma: Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod, 2000; 90(5); 612-17

19.. Weindel K, Marmé D, Weich HA, AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma cells in culture express vascular endothelial growth factor: Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1992; 183(3); 1167-74

20.. Fernández-Sánchez M, Iglesias MC, Ablanedo-Terrazas Y, Steroids are a risk factor for Kaposi’s sarcoma-immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome and mortality in HIV infection: Aids, 2016; 30(6); 909-14

21.. Bihl F, Mosam A, Henry LN, Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-specific immune reconstitution and antiviral effect of combined HAART/chemotherapy in HIV clade C-infected individuals with Kaposi’s sarcoma: AIDS, 2007; 21(10); 1245-52

22.. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement: Int J Surg, 2010; 8(5); 336-41

23.. Sobel RK, Carter KD, Allen RC, Periorbital edema: A puzzle no more?: Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 2012; 23(5); 405-14

24.. Andersen MF, Longhurst HJ, Rasmussen ER, Bygum A, How not to be misled by disorders mimicking angioedema: A review of pseudoangioedema: Int Arch Allergy Immunol, 2016; 169(3); 163-70

25.. Frans E, Blockmans D, Peetermans W, Kaposi’s sarcoma presenting as generalized lymphedema: Acta Clin Belg, 1994; 49(1); 19-22

26.. Bossuyt L, Van den Oord JJ, Degreef H, Lymphangioma-like variant of AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma with pronounced edema formation: Dermatology, 1995; 190(4); 324-26

27.. Schwartz RA, Spicer MS, Thomas I, Ecchymotic Kaposi’s sarcoma: Cutis, 1995; 56(2); 104-6

28.. Hengge UR, Stocks K, Goos M, Acquired immune deficiency syndrome-related hyperkeratotic Kaposi’s sarcoma with severe lymphoedema: Report of five cases: Br J Dermatol, 2000; 142(3); 501-5

29.. Bautista M, Flores D, Chadha A, Kaposi’s sarcoma: Another cause of middle lobe syndrome: Am J Med, 2001; 111(7); 585-86

30.. Connick E, Kane MA, White IE, Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome associated with Kaposi sarcoma during potent antiretroviral therapy: Clin Infect Dis, 2004; 39(12); 1852-55

31.. Volkow PF, Cornejo P, Zinser JW, Life-threatening exacerbation of Kaposi’s sarcoma after prednisone treatment for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: AIDS, 2008; 22(5); 663-65

32.. Feller L, Khammissa RA, Wood NH, Facial lymphoedema as an indicator of terminal disease in oral HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma: SADJ, 2010; 65(1); 14-18

33.. Kunal Patel CT, Cervellione KL, Bagheri F, Maruf M, Rapidly progressive Kaposi’s sarcoma with prominent oral and pulmonary manifestations in an HIV patient: Am J Resp Crit Care Med, 2012; 185; A6200

34.. Chabria S, Barakat L, Ogbuagu O, Steroid-exacerbated HIV-associated cutaneous Kaposi’s sarcoma immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: ‘Where a good intention turns bad’: Int J STD AIDS, 2016; 27(11); 1026-29

35.. Call C, Sareen A, Salazar V, When steroids don’t fix the swelling: A case of delayed Kaposi’s sarcoma diagnosis [Abstract] 2021; Available from: . Abstract published at SHM Converge 2021. Abstract 377 Journal of Hospital Medicine. September 27th 2022.https://shmabstracts.org/abstract/when-steroids-dont-fix-the-swelling-a-case-of-delayed-kaposis-sarcoma-diagnosis/

Figures

In Press

06 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942937

12 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943244

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943275

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943411

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250