25 July 2020: Articles

Unusual Early Recovery of a Critical COVID-19 Patient After Administration of Intravenous Vitamin C

Unusual clinical course, Unusual or unexpected effect of treatment

Hafiz Muhammad Waqas Khan1ABEF*, Niraj Parikh2AF, Shady Maher Megala3AF, George Silviu Predeteanu1AEFDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.925521

Am J Case Rep 2020; 21:e925521

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) continues to spread, with confirmed cases now in more than 200 countries. Thus far there are no proven therapeutic options to treat COVID-19. We report a case of COVID-19 with acute respiratory distress syndrome who was treated with high-dose vitamin C infusion and was the first case to have early recovery from the disease at our institute.

CASE REPORT: A 74-year-old woman with no recent sick contacts or travel history presented with fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Her vital signs were normal except for oxygen saturation of 87% and bilateral rhonchi on lung auscultation. Chest radiography revealed air space opacity in the right upper lobe, suspicious for pneumonia. A nasopharyngeal swab for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 came back positive while the patient was in the airborne-isolation unit. Laboratory data showed lymphopenia and elevated lactate dehydrogenase, ferritin, and interleukin-6. The patient was initially started on oral hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin. On day 6, she developed ARDS and septic shock, for which mechanical ventilation and pressor support were started, along with infusion of high-dose intravenous vitamin C. The patient improved clinically and was able to be taken off mechanical ventilation within 5 days.

CONCLUSIONS: This report highlights the potential benefits of high-dose intravenous vitamin C in critically ill COVID-19 patients in terms of rapid recovery and shortened length of mechanical ventilation and ICU stay. Further studies will elaborate on the efficacy of intravenous vitamin C in critically ill COVID-19.

Keywords: Ascorbic Acid, COVID-19, Intensive Care Units, Respiration, Artificial, Betacoronavirus, COVID-19, Coronavirus Infections, Infusions, Intravenous, Pandemics, Pneumonia, Viral, Recovery of Function, SARS-CoV-2, Vitamins

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first reported on December 31, 2019 in a group of patients who presented with atypical pneumonia in Wuhan, Hubei province, China [1,2]. Since the first report of the disease, more than 3 million cases have been reported worldwide, with the United States as the epicenter of this pandemic, with more than 1 million confirmed cases and more than 50 000 deaths as of April 28, 2020 [3]. Studies from various countries have reported that COVID-19 is associated with rapid spread, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), saturated capacity of intensive care units, and high mortality [4,5].

There are still no targeted therapeutic options available for SARS-CoV-2, and symptomatic management is the mainstay of treatment in ARDS associated with COVID-19. The mortality rate associated with ARDS is up to 45%, which is almost equal to the 50% case fatality rate reported in patients with severe COVID-19 disease requiring critical care management [6,7]. Multiple studies have found that high-dose intravenous vita-min C reduces systemic inflammation in multiple ways, including attenuation of cytokine surge, and prevents lung injury in severe sepsis and ARDS [8,9].

We describe a case of COVID-19 with septic shock and ARDS who received high doses of intravenous vitamin C and was the first case to be able to be taken off of mechanical ventilation (MV) early and recover from the disease at our institute.

Case Report

A 74-year-old white woman presented to the Emergency Department with a 2-day history of low-grade fever, dry cough, and shortness of breath (SOB). She had been admitted to another hospital for an elective right total knee replacement 1 week ago, with an uneventful post-operative course. She went to the hospital in a healthy state, stayed in a private room, and denied any recent sick contacts or travel history.

Upon review of systems, the patient reported pain, redness, and swelling in the right knee, which was unchanged since the surgery. The past medical history was pertinent for essential hypertension, obesity, myasthenia gravis (MG) in remission, and osteoarthritis.

The physical examination revealed a body temperature of 37.3°C, blood pressure of 121/82, pulse of 87 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation of 87% while breathing ambient air. Lung auscultation revealed bilateral rhonchi with rales. Chest radiography (CXR) was performed, which reported patchy air space opacity in the right upper lobe suspicious for pneumonia (Figure 1). The remainder of the examination was unremarkable.

A rapid nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) for influenza A and B was negative. Given community transmission of COVID-19, a nasopharyngeal swab specimen was obtained and sent to the state laboratory for detection of SARS-CoV-2. The patient was admitted to the airborne-isolation unit following the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for contact, droplet, and airborne precautions [10].

The patient was initially started on broad-spectrum antibiotics with cefepime and levofloxacin for pneumonia in the high-risk setting of recent hospitalization for knee surgery after drawing blood and sputum cultures along with supportive care with 2 L of supplemental oxygen. On day 3, the patient also developed mild diarrhea, generalized weakness, and fatigue. She was evaluated by Neurology and started on 1 g/kg intravenous immunoglobulin for 4 days due to mild MG exacerbation and a pending MG crises.

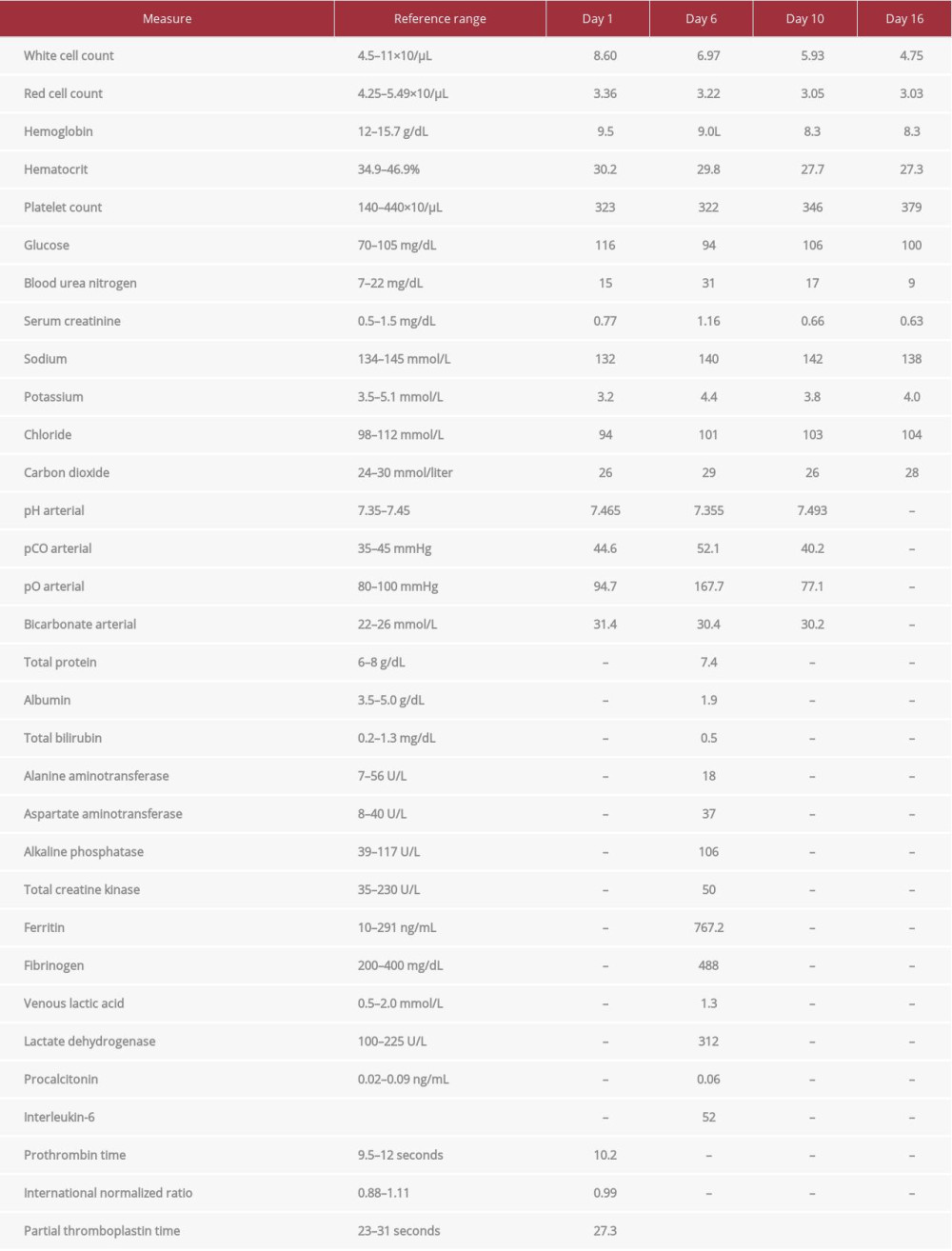

The arterial blood gases (ABGs), complete blood count, and basic metabolic profile studies were monitored during hospitalization and are presented in Table 1. The laboratory data on day 1 showed mild absolute lymphopenia and anemia, while the ABGs revealed a pH of 7.46, pCO2 of 44.6 mmHg, pO2 of 94.7 mmHg, and bicarbonate of 31.4 mmol/L. On day 6, the creatinine kinase and lactic acid were normal, while the lactate dehydrogenase, ferritin, and interleukin-6 were elevated at 312 units per liter, 767 nanograms per milliliter, and 52 pico-grams per milliliter, respectively.

On days 1 through 4 of hospitalization, the patient reported progressively increasing SOB, and the oxygen requirements increased up to 10 L high-flow nasal cannula. On day 4, the nasopharyngeal swab results came back positive for SARSCoV-2 by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RTPCR). The patient was started on oral hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once and started on 200 mg twice a day, along with azithromycin 500 mg once a day intravenously, zinc sulfate 220 mg 3 times a day, and oral vitamin C 1 g twice a day. The blood and sputum cultures did not grow any organisms and broad-spectrum antibiotics were discontinued.

On day 6, the patient’s SOB worsened rapidly, and oxygen requirements went up to 15 L. Upon physical examination, the patient was drowsy, in moderate distress, and was unable to protect the airways. The blood pressure was 78/56 mmHg with the heart rate of 112 beats per minute, temperature 38°C, and a respiratory rate of 28 breaths per minute. The CXR revealed bilateral alveolar infiltrates due to pneumonia and interstitial edema, consistent with ARDS (Figure 2). Given her rapid deterioration, she was intubated on an emergent basis and started on pressure-regulated volume-controlled mechanical ventilation.

The patient was started on norepinephrine 0.02 mcg/kg/min for septic shock and was titrated accordingly to maintain mean arterial pressure more than 65 mmHg, along with colchicine 0.6 mg twice a day to address the cytokine storm given the elevated interleukin-6 levels. On day 7 [mechanical ventilation (MV) day 2], she was started on high-dose vita-min C 11 g per 24 h as a continuous intravenous infusion. Her clinical condition started to improve slowly and norepinephrine support was stopped on MV day 4. The CXR on day 10 showed significant improvement of the pneumonia and interstitial edema (Figure 3). A spontaneous breathing trial with continuous positive airway pressure/pressure support (CPAP/PS) with the settings of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 7 mmHg, PS above PEEP of 10 mmHg, and a fraction of inspired oxygen of 40% was successfully tolerated by the patient. The ABGs revealed a pH of 7.49 mmHg, pCO2 of 40.2 mmHg, pO2 of 77.1 mmHg, and bicarbonate of 30.2 mmol/L. Because of her remarkable clinical and radiological improvement, she was extubated to 4 L of oxygen with a nasal cannula on day 10 of illness (MV day 5). Her breathing status continued to improve in the following days, with oxygen saturation of 92% on day 16 of illness while breathing ambient air, and a CXR revealed almost complete resolution of the infiltrates (Figure 4).

The patient received a total of 5 days of treatment with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin along with 4 days of colchicine during hospitalization. High-dose vitamin C infusion and oral zinc sulfate were continued for a total of 10 days. She received inpatient physical and occupational rehabilitation after being transferred from the Critical Care Unit to an isolation room. She still positive by RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 on day 16 of illness and was discharged from the hospital in stable condition with an additional 14 days of quarantine.

Discussion

SARS-CoV-2 continues to spread across the world causing severe illness in the form of septic shock, multiorgan failure, ARDS, and death. The virus was first named 2019-nCoV when the initial cases of atypical pneumonia in China were found to be associated with a novel coronavirus [2]. It was later named SARS-CoV-2 as it was found to cause ARDS, requiring high-support mechanical ventilation and associated high mortality [4,5]. Thus far, there are no specific targeted therapies with proven efficacy available for the treatment of critically ill patients with ARDS. In our case, the patient was treated with high-dose vita-min C as a continuous intravenous infusion and was the first COVID-19 patient to be able to be taken off mechanical ventilation early and recover from the disease at our institution.

Many decades of research have shown that vitamin C is an essential component of the immune cell function and has a critical role in a variety of immune system mechanisms [11]. Patients with vitamin C deficiency can develop fatal scurvy and are highly susceptible to a variety of infections, including pneumonia [12]. Vitamin C enhances neutrophil motility, phagocytosis, microbial killing by activating reactive oxygen species, and apoptosis, and prevents oxidative damage by its antioxidant properties [13]. It also promotes B and T lymphocytes proliferation and antibody production [14].

Recent data have shown that vitamin C also prevents the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, which causes lung injury and leads to ARDS; this is a component of the cytokine release syndrome that is observed in critically ill COVID-19 patients [15]. The attenuation of these immune functions by microorganisms leads to a severe inflammatory state and tissue necrosis resulting in multiorgan failure and ARDS, requiring mechanical ventilation and ICU care. Various studies have shown that up to 75% of critically ill COVID-19 patients require invasive mechanical ventilation in the ICU [16,17].

A recent meta-analysis of multiple trials showed that vitamin C reduces the duration of mechanical ventilation and the length of ICU stay in patients with severe sepsis and ARDS [18]. This finding was also confirmed recently in a randomized clinical trial by Fowler et al. involving 167 patients with sepsis and ARDS who received high-dose intravenous vitamin C up to 15 g per day and showed significant improvement in 28-day mortality and shortened duration of ICU stay [19].

Based on the above data, vitamin C has been increasingly used recently in the treatment of COVID-19 disease, and Peng et al., from Wuhan University, initiated a phase II trial to study the efficacy of vitamin C infusion in the treatment of ARDS associated with SARS-CoV-2, in which patients receive 24 g of intravenous vitamin C per day for a total of 7 days [20]. Vitamin C infusion was not part of the treatment for COVID-19 at our institute as it has not been approved as a standard treatment for SARS-CoV-2. The present patient received high-dose vita-min C infusion due to family request after the development of ARDS and MV initiation.

According to a study by Bhatraju et al., who investigated COVID-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region, the median length of ICU stay and duration of MV were 14 and 10 days, respectively [16]. In our case, the length of ICU stay and duration of MV were only 6 and 5 days, respectively. Our case was also the first to be able to be taken off of MV early in our COVID-19 ICU unit and to recover from the disease at our institute. The length of ICU stay and duration of MV in the present patient were also lower than in COVID-19 patients who did not receive vitamin C infusion at our institute. The rest of the hospital course of our case was uneventful and the patient was discharged home in stable condition.

Conclusions

Vitamin C is a pivotal component of the immune system, with proven antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and has been tested in numerous studies for its role in severe sepsis and ICU care, especially when used as a continuous high-dose intravenous infusion. High-dose intravenous vitamin C treatment in our case was associated with fewer days on mechanical ventilation, shorter ICU stay, and earlier recovery compared to the average length of mechanical ventilation, disease duration, and ICU stay in critical COVID-19 patients at our institute. Our results show the importance of further investigation of intravenous vitamin C in the form of randomized controlled trials for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 to accurately assess its efficacy in critically ill COVID-19 patients requiring mechanical ventilation and ICU care.

Figures

References:

1.. , Pneumonia of unknown etiology. China – 2020 Available from: ()https://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en/

2.. , Novel-coronavirus. China – 2020 Available from: ()https://www.who.int/csr/don/12-january-2020-novel-coronavirus-china/en/

3.. , Coronavirus COVID-19 global cases dashboard Available from: ()https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6/

4.. Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study [Erratum in: Lancet Respir Med, 2020; 8(4): e26]: Lancet Respir Med, 2020; 8(5); 475-81

5.. Grasselli G, Pesenti A, Cecconi M, Critical care utilization for the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: Early experience and forecast during an emergency response: JAMA, 2020 [Online ahead of print]

6.. Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 countries [Erratum in: JAMA, 2016; 316(3): 350. Erratum in: JAMA, 2016; 316(3): 350]: JAMA, 2016; 315(8); 788-800

7.. Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State: JAMA, 2020; 323(16); 1612-14

8.. Fisher BJ, Seropian IM, Kraskauskas D, Ascorbic acid attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury: Crit Care Med, 2011; 39(6); 1454-60

9.. Fowler AA, Syed AA, Knowlson S, Phase I safety trial of intravenous ascorbic acid in patients with severe sepsis: J Transl Med, 2014; 12; 32

10.. : Infection control. 2019 Novel-coronavirus, China Available from: ()https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/infection-control.html

11.. Maggini S, Wintergerst ES, Beveridge S, Hornig DH, Selected vitamins and trace elements support immune function by strengthening epithelial barriers and cellular and humoral immune responses: Br J Nutr, 2007; 98(Suppl. 1); S29-35

12.. Hemilä H, Vitamin C and Infections: Nutrients, 2017; 9(4); 339

13.. Carr AC, Maggini S, Vitamin C and immune function: Nutrients, 2017; 9(11); 1211

14.. Campbell JD, Cole M, Bunditrutavorn B, Vella AT, Ascorbic acid is a potent inhibitor of various forms of T cell apoptosis: Cell Immunol, 1999; 194(1); 1-5

15.. Portugal CC, Socodato R, Canedo T, Caveolin-1-mediated internalization of the vitamin C transporter SVCT2 in microglia triggers an inflammatory phenotype: Sci Signal, 2017; 10(472); eaal2005

16.. Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle Region – case series: N Engl J Med, 2020; 382(21); 2012-22

17.. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China: JAMA, 2020; 323(11); 1061-69

18.. Hemilä H, Chalker E, Vitamin C can shorten the length of stay in the ICU: A meta-analysis: Nutrients, 2019; 11(4); 708

19.. Fowler AA, Truwit JD, Hite RD, Effect of vitamin C infusion on organ failure and biomarkers of inflammation and vascular injury in patients with sepsis and severe acute respiratory failure: The CITRIS-ALI Randomized Clinical Trial: JAMA, 2019; 322(13); 1261-70

20.. , Vitamin C Infusion for the Treatment of Severe 2019-nCoV Infected Pneumonia )https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04264533

Figures

In Press

12 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943244

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943275

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943411

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942864

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250