06 November 2021: Articles

Increased Ileostomy Output as an Indicator of Thyroid Storm in a Patient without an Established History of Underlying Thyroid Disease

Unusual clinical course, Challenging differential diagnosis, Management of emergency care

Abraar Muneem1ABCDEFG, Muhammed A. Rahim1ABCDEFG, Kunal KaramchandaniDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.933751

Am J Case Rep 2021; 22:e933751

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Thyroid storm, also known as thyrotoxic crisis, is a rare but life-threatening endocrine emergency that presents with multisystem involvement. Patients present with pronounced signs of hyperthyroidism, fever, tachycardia, and differing severities of multisystem dysfunction and decompensation. Early recognition and prompt initiation of treatment are important. The development of thyroid storm in patients with no established history of underlying hyperthyroidism is rare.

CASE REPORT: In this case report, we describe the occurrence of thyroid storm in a 27-year-old man without an established history of underlying thyroid disease, who was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) with a high ileostomy output and fever. Although initially treated for possible sepsis, the diagnosis of thyroid storm was made only after a thorough workup was initiated and he was found to have underlying Graves’ disease. Prompt treatment resulted in the resolution of symptoms and avoided potential morbidity and mortality.

CONCLUSIONS: This case highlights the potential difficulty in diagnosing thyroid storm in a patient admitted to the ICU without an established history of hyperthyroidism. Upgrade in care, timely diagnosis, and initiation of appropriate therapy led to a favorable outcome. Clinicians should consider hyperthyroidism as a possible cause of high ileostomy output, especially when it does not resolve with traditional treatment and no obvious cause can be identified. This case demonstrates the challenges presented when the patient’s history and clinical signs are ambiguous and stresses the importance of “outside the box” thinking.

Keywords: Fever, hyperthyroidism, Ileostomy, Intensive Care, Thyrotoxicosis, Graves Disease, Humans, Intensive Care Units, Male, Sepsis, Thyroid Crisis

Background

Thyroid storm, also known as thyrotoxic crisis, is a rare but life-threatening endocrine emergency that presents with multisystem involvement. Patients present with pronounced signs of hyperthyroidism and differing severities of multisystem dys-function and decompensation [1]. Most commonly, the clinical presentation of thyroid storm involves a high-grade fever, tachycardia, mental status changes, nausea, and vomiting [2]. The progression and manifestation of thyroid storm can occur rapidly within hours, and, therefore, once thyroid storm is recognized, the patient should be managed in an appropriate location such as an Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Although the incidence is low, the mortality associated with this condition is estimated to be about 10% to 20% despite significant advancements in its treatment [1]. Early recognition and prompt initiation of treatment is important. In patients with known hyperthyroidism, thyroid storm is often precipitated by several different events, including infection, surgery, stress, major trauma, iodine exposure from radiocontrast dyes, or amiodarone [3]. The most common etiology is a history of underlying Graves’ disease. The development of thyroid storm in patients with no known history of underlying hyperthyroidism is rare.

In this case report, we describe the occurrence of thyroid storm in a patient with no established history of underlying thyroid disease who was admitted to the ICU with a high ileostomy output and fever. The diagnosis of thyroid storm can be challenging when clinical signs are vague and ambiguous. We aim to emphasize high ileostomy output as an early clinical indicator of thyroid storm and provide insight into the diagnosis of thyroid storm in individuals with no known underlying thyroid disorder.

Case Report

A 27-year-old man with past medical history significant for ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis who had undergone total abdominal colectomy with end-ileostomy 4 months prior presented to the Emergency Department with abdominal pain, high ileostomy output, and 9-kg weight loss over the last 7 days. His weight was 58.2 kg on admission. This was the patient’s third hospital admission over the past 4 weeks for a small bowel obstruction with high ileostomy output. The prior 2 admissions were medically managed and resolved within a few days. The patient’s home medications included pantoprazole 40 mg, ursodiol 300 mg twice daily, and lorazepam 0.5 mg as needed. Social history included occasional alcohol consumption, but no smoking history or illicit drug use.

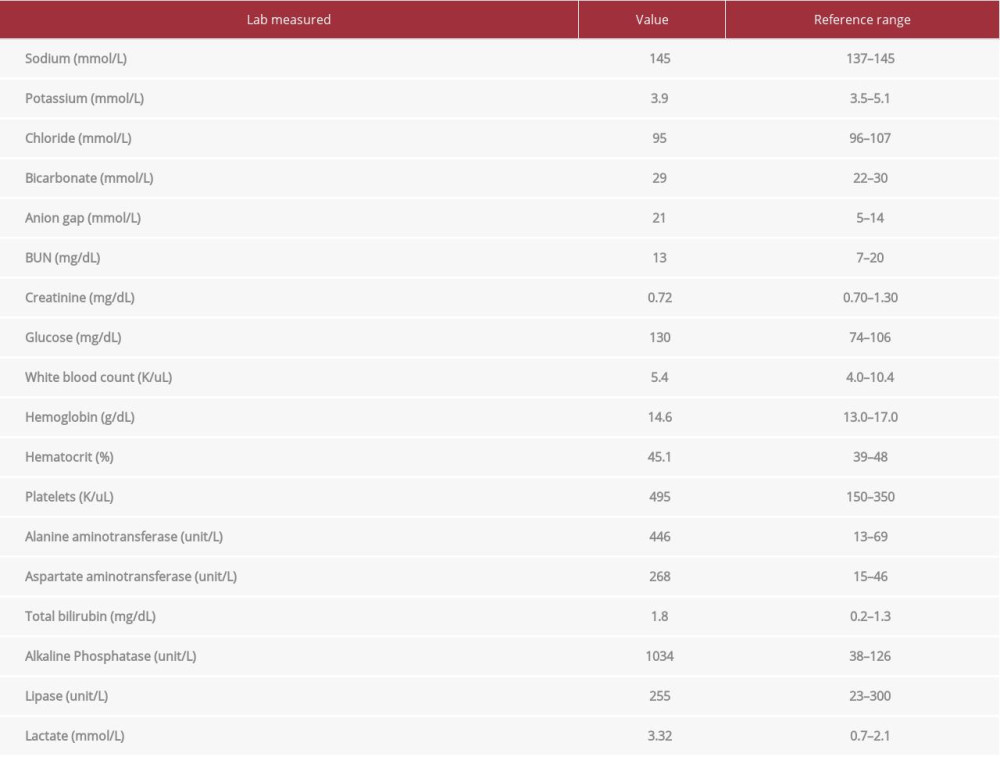

Upon presentation to the Emergency Department, the patient had tachycardia (heart rate of 170 beats/min), was afebrile, and had a blood pressure of 103/74 mm Hg. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen with intravenous contrast showed dilated loops of bowel to the level of the colostomy, similar to previous imaging findings. Remarkable laboratory values included a white blood cell count of 5.4 K/uL (reference range, l 4.0–10.4 K/uL), alanine aminotransferase of 446 unit/L (range, 13–68 unit/L), aspartate aminotransferase of 268 unit/L (range, 15–46 unit/L), alkaline phosphatase of 1034 unit/L (range, 38–126 unit/L), and a point of care lactate of 3.32 mmol/L (range, 0.7–2.1 mmol/L). The complete laboratory values are presented in Table 1. The patient was admitted to the ward of colorectal surgery services, kept nil-peros status, and resuscitated with 1900 mL of intravenous fluids (IVF) in the form of lactated Ringer’s solution (LR), and a nasogastric tube was placed for decompression and supportive care of his small bowel obstruction. Parenteral nutrition was not used. Subsequent upper endoscopy revealed chronic active ileitis. Medications included metoprolol tartrate 25 mg twice daily for tachycardia, hydromorphone 0.2 mg every 4 h, ondansetron 4 mg every 6 h, acetaminophen 1000 mg every 8 h, and home medication of pantoprazole 40 mg. Over the next 24 to 48 h, the patient remained afebrile but continued to have tachycardia (heart rate of 150–180 beats/min), with ostomy output >5 L/day despite aggressive IVF resuscitation (7272 mL of LR on hospital day 2). On hospital day 3, the patient spiked a fever, with a temperature as high as 39.7°C, and developed tachypnea (respiratory rate of 32 breaths/min), tachycardia (128 beats/min), leukopenia (3.89 k/uL), mild agitation, and worsening abdominal pain. He continued to have increased ileostomy output. C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate laboratory values were not measured. These findings raised the suspicion for possible sepsis, given the patient met the criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome. The patient was upgraded to the ICU for further management.

In the ICU, the patient was treated for possible sepsis with IVF resuscitation (6982 mL of LR on day 3 of the hospital course), which was assessed by fluid responsiveness, and broad spectrum antibiotics (piperacillin-tazobactam 3.375 g every 6 h). Also, a pre-existing peripherally inserted central catheter was removed. He was also given a dose of metoprolol tartrate 12.5 mg for tachycardia. Parenteral nutrition was not used. Repeated CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed a small bowel obstruction up to the stoma, consistent with previous CT imaging. Results of a blood workup, including a complete blood count, basic metabolic profile, and blood lactate levels, were within normal limits. The patient had negative urine and blood cultures, a negative

Following initiation of therapy, the patient’s ileostomy output steadily decreased from 5175 mL/24 h on the day treatment began to 2150 mL/24 h 4 days later. As the patient’s hospital course continued, his fevers resolved, and he was discharged home 17 days after his initial admission, with 3 of those days spent in the ICU. After his time in the ICU, he returned to the colorectal surgery services ward until discharge. Changes in the patient’s body temperature and ileostomy output through the first 8 days of the hospital course are shown in Figure 1. No additional distinct laboratory trends were noted other than those previously stated. He was given recommendations to undergo total thyroidectomy. Discharge medications included propranolol 30 mg twice daily, propylthiouracil 200 mg twice daily, and prednisone 10 mg.

Discussion

This case highlights the challenges associated with diagnosing thyroid storm in a patient admitted to the ICU without a previously established history of hyperthyroidism. Our patient, with a history of ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis, presented with abdominal pain, weight loss, and high ileostomy output attributed to small bowel obstruction. He went on to develop sinus tachycardia, high-grade fevers, and agitation, leading to ICU admission. Although he was initially treated for possible sepsis, the diagnosis of thyroid storm was established only after a thorough workup was initiated. Prompt treatment then led to the resolution of symptoms and avoided potential morbidity and mortality.

Among all endocrine emergencies, thyroid storm ranks as one of the most critical illnesses. The diagnosis of thyroid storm is based on clinical presentation and findings, and patients typically display signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism accompanied by manifestations of multisystem dysfunction [1]. Multisystem dysfunction of the cardiovascular system, thermoregulatory system, gastrointestinal-hepatic system, and central nervous system are common, and the Burch-Wartofsky scoring system is often used to standardize the diagnosis [1,4]. Our patient’s presentation corresponded with the classic clinical presentation of thyroid storm [5], which includes altered mentation, hyperpyrexia, tachycardia, nausea, and vomiting. However, in the absence of a history of hyperthyroidism, sepsis was considered as the most likely cause, and further testing was only initiated after the workup for sepsis was negative. On the Burch-Wartofsky scale, our patient received a score of 50, which is highly suggestive of thyroid storm. We suggest that a high degree of suspicion for thyroid storm should be maintained in patients presenting with fever and gastrointestinal and/or central nervous system symptoms in the absence of other signs of infection.

Although the exact pathophysiologic mechanism of thyroid storm is not clear, a superimposed insult often exacerbates underlying simple thyrotoxicosis into the full-blown metabolic crisis of thyroid storm. Stressors such as non-thyroid surgery, childbirth, extensive trauma, infection, or iodine exposure from radiocontrast dyes can induce thyroid storm in patients with unrecognized thyrotoxicosis [6,7]. A typical dose of iodinated contrast medium contains about 13 500 μg of free iodide and 15 to 60 g of bound iodine, which represents an acute iodide load of 90 times to several hundred thousand times the recommended daily intake of 150 μg in adults [8]. Although it is unclear how much iodine our patient may have been exposed to, we believe that our patient’s underlying Grave’s disease was exacerbated by increased exposure to radiocontrast dye. Although a higher prevalence of hyperthyroidism in patients with inflammatory bowel disease has been reported, it is uncertain whether the findings of Graves’ disease in our patient was the extra-intestinal manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease or that of a separate entity [9]. Further research is needed to better understand this possible relationship. Nonetheless, it is likely that the subtle signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism were missed in our patient and the frequent exposure to iodinated contrast during the CT scans (>4 in the month preceding the index admission) precipitated the thyroid storm.

The Burch-Wartofsky Point Scale is a scoring system commonly used to aid in the diagnosis of thyroid storm when sufficient clinical suspicion is present [4]. Specific gastrointestinal symptoms which contribute to this scoring include diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and unexplained jaundice. Since our patient had an end-ileostomy, the high stoma output, which was attributed to a small bowel obstruction, could have been a manifestation of thyrotoxicosis. The persistence of high stoma output despite aggressive fluid resuscitation, nasogastric decompression, use of bowel anti-motility agents, and resolution soon after initiation of appropriate therapy makes this likely. The signs and symptoms seen in thyroid storm are attributed to an overactive thyroid gland, and the gland also produces motilin, which increases gastric and small intestine motility through smooth muscle contractions [10,11]. In the present case, the increased levels of motilin produced in the setting of thyroid storm likely resulted in increased ileostomy output. Once management for thyroid storm began with appropriate pharmacotherapy, the patient’s ileostomy output decreased, followed by a delayed resolution of his fevers. These findings may suggest that a decrease in ostomy output could be an earlier indicator of thyroid storm resolution than is a decrease in core body temperature. Clinicians should consider hyperthyroidism as a possible cause of high ileostomy output, especially when it does not resolve with traditional treatment and no obvious cause can be identified. Additionally, the volume of ileostomy output can be measured thereafter as an indicator of treatment responsiveness.

Conclusions

Our case report describes a patient who presented with high ileostomy output as a predominant symptom, had no previous history of hyperthyroidism, and developed thyroid storm precipitated by frequent exposure to iodinated contrast. Upgrade in care, timely diagnosis, and initiation of appropriate therapy led to a favorable outcome. This case demonstrates the potential difficulty in diagnosing thyroid storm when the history and clinical signs are ambiguous and stresses the importance of thinking “outside the box”.

References:

1.. Chiha M, Samarasinghe S, Kabaker AS, Thyroid storm: An updated review: J Intensive Care Med, 2015; 30(3); 131-40

2.. Pokhrel B, Aiman W, Bhusal K: Thyroid storm, 2021, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448095/

3.. Idrose AM, Acute and emergency care for thyrotoxicosis and thyroid storm: Acute Med Surg, 2015; 2(3); 147-57

4.. Burch HB, Wartofsky L, Life-threatening thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid storm: Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am, 1993; 22(2); 263-77

5.. Shahid M, Kiran Z, Sarfraz A, Presentations and outcomes of thyroid storm: J Coll Physicians Surg Pak, 2020; 30(3); 330-31

6.. Nayak B, Burman K, Thyrotoxicosis and thyroid storm: Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am, 2006; 35(4); 663-86

7.. Blick C, Nguyen M, Jialal I: Thyrotoxicosis, 2021, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482216/

8.. Dunne P, Kaimal N, MacDonald J, Syed AA, Iodinated contrast-induced thyrotoxicosis: CMAJ, 2013; 185(2); 144-47

9.. Shizuma T, Concomitant thyroid disorders and inflammatory bowel disease: A literature review: Biomed Res Int, 2016; 2016; 5187061

10.. Al-Missri MZ, Jialal I: Physiology, motilin, 2021, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545309/

11.. Carroll R, Matfin G, Endocrine and metabolic emergencies: Thyroid storm: Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab, 2010; 1(3); 139-45

Figures

In Press

06 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942937

12 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943244

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943275

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943411

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250