23 February 2022: Articles

Sickle Cell Trait and SARS-CoV-2-Induced Rhabdomyolysis: A Case Report

Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Gabriele Donati1AE, Chiara Abenavoli1BF, Gisella Vischini1E, Giovanna Cenacchi23C, Roberta Costa23C, Gianandrea Pasquinelli4C, Manuela FerracinDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.934220

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e934220

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Rhabdomyolysis is a syndrome characterized by muscle necrosis and the subsequent release of intracellular muscle constituents into the bloodstream. Although the specific cause is frequently evident from the history or from the immediate events, such as a trauma, extraordinary physical exertion, or a recent infection, sometimes there are hidden risk factors that have to be identified. For instance, individuals with sickle cell trait (SCT) have been reported to be at increased risk for rare conditions, including rhabdomyolysis. Moreover, there have been a few case reports of SARS-CoV-2 infection-related rhabdomyolysis.

CASE REPORT: We present a case of a patient affected by unknown SCT and admitted with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia, who suffered non-traumatic non-exertional rhabdomyolysis leading to acute kidney injury (AKI), requiring acute hemodialysis (HD). The patients underwent 13 dialysis session, of which 12 were carried out using an HFR-Supra H dialyzer. He underwent kidney biopsy, where rhabdomyolysis injury was ascertained. No viral traces were found on kidney biopsy samples. The muscle biopsy showed the presence of an “open nucleolus” in the muscle cell, which was consistent with virus-infected cells. After 40 days in the hospital, his serum creatinine was 1.62 mg/dL and CPK and Myoglobin were 188 U/L and 168 ng/mL, respectively; therefore, the patient was discharged.

CONCLUSIONS: SARS-CoV-2 infection resulted in severe rhabdomyolysis with AKI requiring acute HD. Since SARS-CoV-2 infection can trigger sickle-related complications like rhabdomyolysis, the presence of SCT needs to be ascertained in African patients.

Keywords: Acute Kidney Injury, COVID-19, rhabdomyolysis, Sickle Cell Trait, COVID-19, Humans, Male, Renal Dialysis, SARS-CoV-2

Background

Rhabdomyolysis is a syndrome characterized by muscle necrosis and the subsequent release into the bloodstream of intra-cellular muscle constituents such as CPK and myoglobin, which are the most sensitive markers of this condition.

The severity of the illness can vary from an asymptomatic elevation in serum muscle enzymes to a life-threatening disease associated with AKI, which is the most serious complication of rhabdomyolysis, regardless of its cause [1].

The causes of rhabdomyolysis are generally divided into 3 categories: traumatic rhabdomyolysis (±muscle compression), non-traumatic exertional rhabdomyolysis, and non-traumatic non-exertional rhabdomyolysis (including drugs, toxins, infections) [2].

Although SCT alone is unlikely to cause muscle damage leading to rhabdomyolysis, simultaneous risk factors, such as infections, could explain some forms of non-traumatic, non-exertional rhabdomyolysis related to this benign heterozygous carrier condition. Indeed, in a recent cross-sectional study reviewing hemoglobin phenotypes in African Americans with end-stage renal disease, SCT was found to be twice as common than in the wider population [2].

Case Report

We report here the case of a 38-year-old African man with no past medical history, who presented to the emergency room with dyspnea requiring oxygen support (the oxygen saturation was 95% with 2 L/min of oxygen therapy via nasal cannula), lower back pain, lower limbs hypostenia, and pharyngodynia. At presentation the arterial blood pressure was 135/80 mmHg, the heart rate was 65 bpm, the body weight was 90 kg, the body temperature was 36.5°C. The patients denied exposure to medication, illicit drug use, or alcohol abuse. No strenuous physical activity was reported. Physical examination showed peripheral edema in the absence of jugular vein distention. Both rapid anti-COVID antigenic and molecular swabs were positive. High-resolution computed tomography showed peripheral ground-glass opacities consistent with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia.

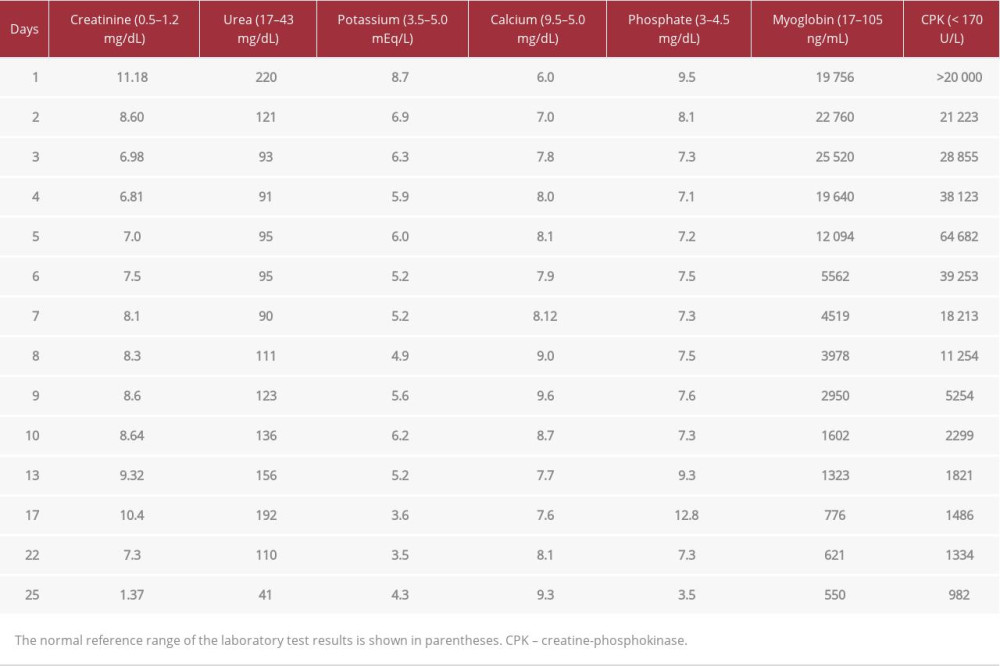

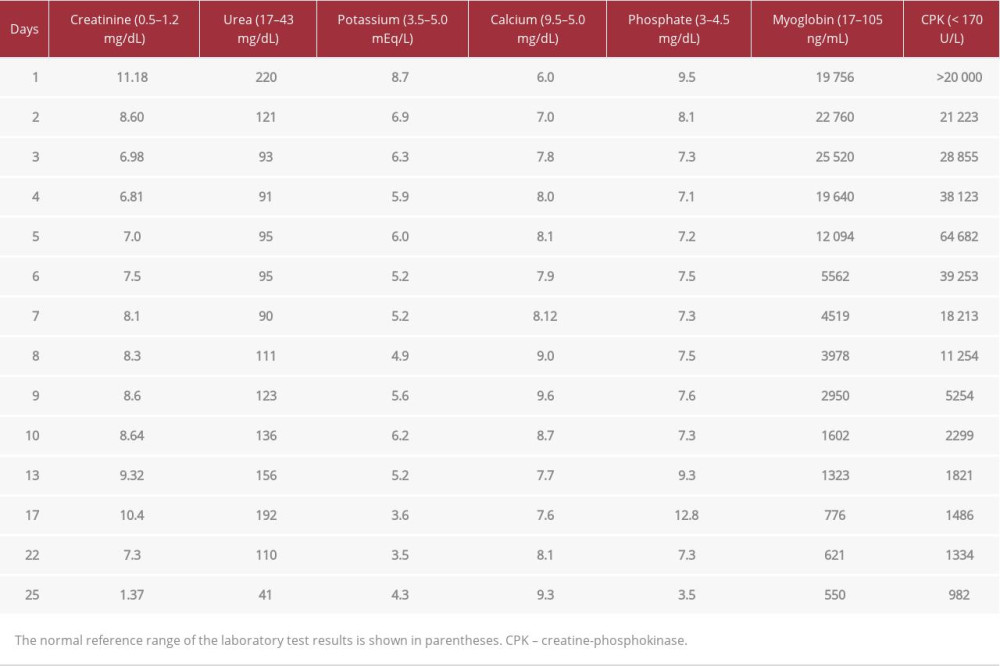

Laboratory tests revealed high urea and creatinine levels (220 mg/dL and 11.18 mg/dL, respectively), electrolytes imbalances, with hyponatremia (126 mmol/L), hypocalcemia (6.0 mg/dL), hyperkalemia (8.7 mmol/L) and hypermagnesemia (4.0 mg/dL), along with elevated levels of liver enzymes (AST 2953 U/L, ALT 623 U/L), LDH (20 881 U/L) and CPK (>20 000 U/L). A diagnosis of rhabdomyolysis with AKI in a SARS-CoV-2-infected patient was done. The patient’s daily laboratory values are shown in Table 1.

Primary human immunodeficiency virus, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus infections were excluded, as well as auto-immune myopathy.

Renal ultrasound did not show any signs of chronic injury, but showed kidneys of increased size (right: 12.5 cm, left: 13 cm), with normal cortical thickness (20 mm) and slightly hyper-echoic bilaterally, supporting the diagnosis of acute kidney damage. The patient was anuric.

A central venous hemodialysis catheter (Mahurkar® Medtronic, Minneapolis, USA, 24 cm length, 12 french diameter) was placed in the right femoral vein and emergency extracorporeal treatment was immediately started through bicarbonate dialysis.

Moreover, high doses of furosemide (250 mg/day) were administered after the first dialysis session. As the need for oxygen support was associated with lung overhydration more than related to the severity of COVID-19 pneumonia, and according to infectious disease experts, steroids were not required.

After the first session of bicarbonate dialysis, urea and creatinine were 121 mg/dl and 8.6 mg/dL, respectively, potassium was 6.9 mEq/l, and myoglobin was 22 760 ng/mL. A new central venous catheter (Mahurkar® Medtronic, 20 cm length, 12 french diameter) was placed in the right jugular vein and the Supra-hemodiafiltration H with endogenous reinfusion technique (HFR-Supra H, Bellco/Medtronic, Mirandola, Italy) was used to increase the removal of myoglobin, to reduce the inflammatory status and to maintain the fluid balance

When the fluid balance was corrected, the oxygen support was withheld and intravenous fluids were administered combined with high-dose furosemide.

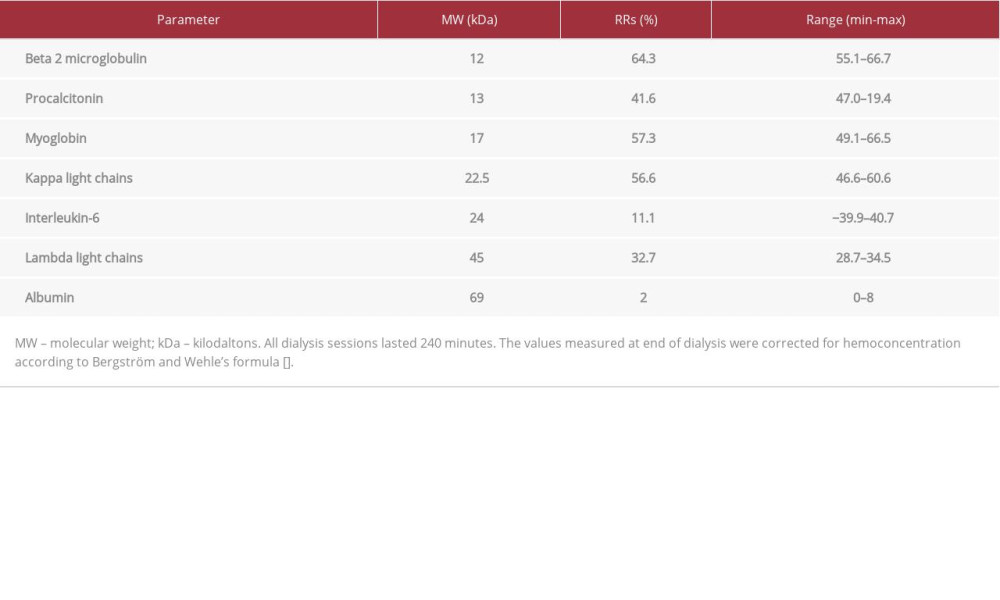

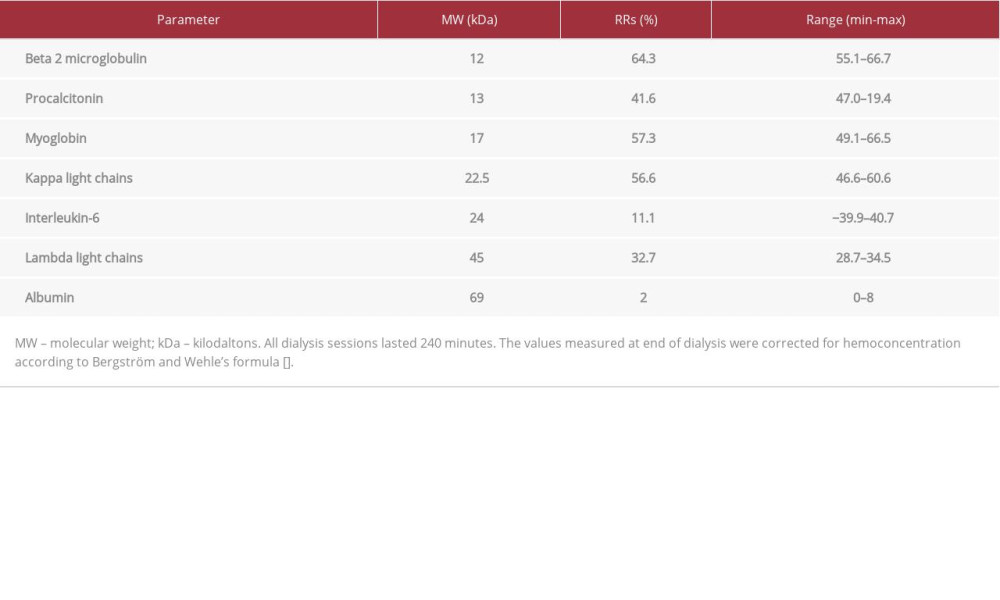

As shown in Table 2, a significant reduction of myoglobin, procalcitonin, and beta 2 microglobulin blood levels per session was obtained after 9 daily dialysis sessions with HFR-Supra H. After 9 HFR-Supra H dialysis sessions, urea and creatinine were 136 mg/dl and 8.64 mg/dL, respectively, potassium was 6.2 mEq/l, and myoglobin was 1602 ng/mL. Dialysis was progressively reduced according to a gradually restoration of urine output, for a total of 13 dialysis sessions.

Both muscle and kidney biopsies were carried out. The former was conducted 11 days after admission, when daily diuresis was about 2 liters/day and serum creatinine was 8.64 mg/dL (eGFR 7 ml/min), while the latter was carried out 8 days later, when daily diuresis was over 3 liters/day and serum creatinine was 7.3 mg/dl (eGFR 9 ml/min).

Quadriceps muscle biopsy showed overwhelming necrosis (Figure 1) along with CD68 macrophages infiltration, likely associated with rhabdomyolysis (Figure 2). The ultrastructural appearance of muscle cell nuclei showed that some of them were characterized by normal outline but by anomalous distribution of chromatin, which was very finely distributed, with some giant perichromatin granules (Figure 3). In particular, the nucleoli of these altered nuclei showed a very peculiar meandering appearance or sometimes they are ring-shaped, indicating an “open” aspect where the nucleolonema is thin thread-like and spread-out as previously described in different types of malignant tumors (Figure 3).

Kidney biopsy showed no glomeruli by light microscopy along with mild-to-moderate acute tubular injury characterized by a focal diffuse globular reddish cast in the distal tubular lumina. Immunofluorescence studies were not performed due to in sufficient renal samples. Electron microscopy, conducted on kidney biopsy samples, revealed acute tubular injury (Figure 4), and interstitial edema with minimal mononuclear cell infiltrates (Figure 5); electron-dense granules with fluffy outline, consistent with hemoglobin/myoglobin casts, were seen in some glomerular capillaries (Figures 6, 7). No electron-dense deposits were found along the glomerular capillary wall, nor were dysmorphic red blood cells casts. The mesangium was unremarkable. The foot process effacements were mild. No viropathic changes were found in glomerular structures or tubules.

The investigation of viral traces on RNA extracted from kidney tissue biopsy was performed using droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) technology and SARS-CoV-2 ddPCR assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories Srl, Cat. 12013743). This highly sensitive assay is able to evaluate viral load by multiplex quantification of SARS-CoV-2 N1 and N2 targets, and human RNase P target as an endogenous internal amplification control (Figure 8A). Of note, while the RNase P target was detected at high concentrations (2123 copies/µl), no positivity was observed for N1 and N2 targets (Figure 8B). Altogether, these results excluded the role of SARS-CoV-2 as a direct cause of AKI.

Considering the low hemoglobin level (7.0 g/dL) and mean cell volume (64 fL), we investigated for pathologic hemoglobin phenotypes. HbS and HbF were 21%, and 3.3%, respectively, consistent with an SCT diagnosis. Then, the patient received a single-unit red blood cell transfusion.

After 22 days, blood tests revealed a progressive normalization of myoglobin and CPK levels (621 ng/mL and 1334 U/L, respectively, compared to 19 756 ng/mL and 20 000 U/L at the time of the admission).

After 40 days in the hospital, as the serum creatinine reached a value of 1.62 mg/dL, urine output was regular, and CPK and myoglobin were 188 U/L and 168 ng/mL, respectively, the patient was discharged and so his renal function has remained normal, with negative urine sediment.

Discussion

We describe a case of non-exertional rhabdomyolysis complicated by AKI due to 2 concomitant factors, a SARS-CoV-2 infection and an SCT. The presence of an “open nucleolus” in the muscle cell seems to reflect a metabolically active cell, as in both virus-infected cells and neoplastic cells [3]. A recent application of a machine-learning model of RNA subcellular localization to SARS-CoV-2 demonstrated viral RNAs showing residency signal for host mitochondria and nucleoli [4].

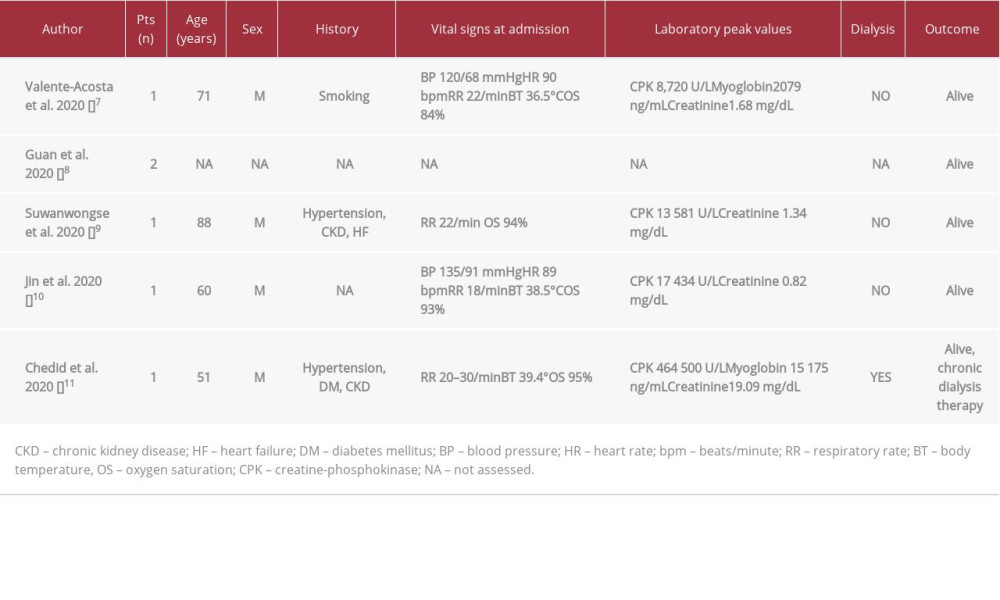

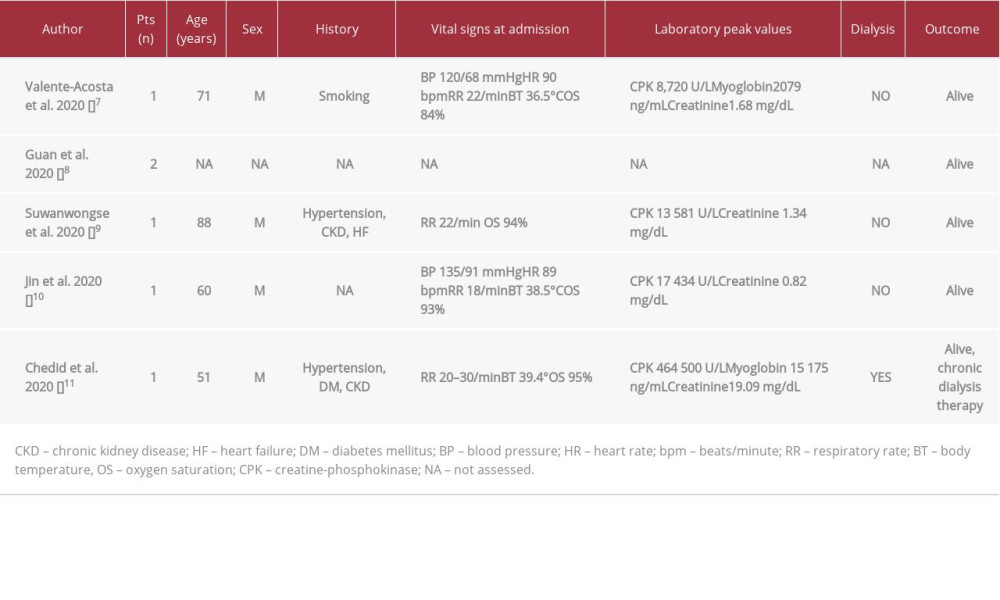

Rhabdomyolysis has been associated with viral infections: influenza A and B, coxsackievirus, Epstein-Barr virus, primary human immunodeficiency virus, and SARS [5,6]. To date, SARS-CoV-2 infection has been considered to be pathogenetic in 6 adult patients affected by rhabdomyolysis (Table 3). Valente-Acosta et al reported the case of a 71-year-old man with AKI KDIGO stage I and respiratory failure who required invasive mechanical ventilation and recovered with supportive therapy and tocilizumab [7]. Guan et al, among 1099 patients affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection in China, reported 2 patients with rhabdomyolysis but they did not show any signs of respiratory failure [8]. Suwanwongse et al described a case of rhabdomyolysis as the presenting problem in an 88-year-old patient with SARS-CoV-2 infection, without respiratory failure but with AKI KDIGO stage I [9]. Jin and Tong described a 60-year-old patient with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia without the need of mechanical ventilation after 9 days in the hospital, who recovered after treatment with antibiotics, interferon inhalation, hydration, alkalization, plasma transfusion, gamma globulin, and symptomatic supportive therapy, and did not show signs of AKI [10]. Finally, Chedid et al described a 51-year-old man with CKD stage 2 who developed SARS-CoV-2 infection and rhabdomyolysis at presentation. The patient did not show any need for mechanical ventilation or for intensive oxygen support. Nonetheless, he developed AKI stage 3 requiring dialysis and, when the AKI did not subside, long-term dialysis was started [11]. However, none of these patients had other risk factors for rhabdomyolysis aside from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

SCT is a genetic risk factor for rhabdomyolysis, especially after strenuous physical activity, but also during viral illness [12]. SCT is present in 7–9% of the African American population [13]. There have been numerous cases documenting severe non-traumatic rhabdomyolysis, particularly among young African Americans participating in strenuous physical activity [2,12]. Nonetheless, conditions of increased oxygen demand may trigger sickle-related complications, even in heterozygotes [14]. Tafty et al described the case of a 33-year-old soldier with SCT admitted for rhabdomyolysis complicated by SARS-CoV-2 infection without pneumonia. Unfortunately, no kidney or muscle biopsies were carried out. He also required hemodialysis for acute kidney injury but recovered his renal function [15].

Conclusions

In our patient, since the muscle biopsy was consistent for SARSCoV-2 dissemination, even if no viral particles were found, the real cause of rhabdomyolysis must have been the combination of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the hypoxemia caused by SARSCoV-2 pneumonia that resulted in red blood cell deformation or sickling. SARS-CoV-2 infection may result in severe rhabdomyolysis with acute kidney injury requiring acute dialysis prescription. Since SARS-CoV-2 infection can trigger sickle-related complications like rhabdomyolysis, the presence of SCT needs to be ascertained in African patients.

Figures

References:

1.. Miller ML, Targoff IN, Shefner MJ, Causes of rhabdomyolysis (accessed 3-3-2021)www. uptodate.com/contents/causes-of-rhabdomyolysis

2.. Janga K, Greenberg S, Oo P, Non traumatic exertional rhabdomyolysis leading to acute kidney injury in a sickle trait positive individual on renal biopsy: Case Rep Nephrol, 2018; 2018; 5841216

3.. Ghadially FN: Ultrastructural pathology of the cell and matrix, 1988; 58-67, Oxford, UK, Butterworths

4.. Wu KE, Fazal FM, Parker KR, RNA-GPS predicts SARS-CoV-2 RNA residency to host mitochondria and nucleolus: Cell Syst, 2020; 11(1); 102-8.e3

5.. Bosch X, Poch E, Grau JM, Rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury: N Engl J Med, 2009; 361; 62-72

6.. Chen LL, Hsu CW, Tian YC, Rhabdomyolysis associated with acute renal failure in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: Int J Clin Pract, 2005; 59; 1162-66

7.. Valente-Acosta B, Moreno-Sanchez F, Fueyo-Rodriguez O, Rhabdomyolysis as an initial presentation in a patient diagnosed with COVID-19: BMJ Case Rep, 2020; 13; e236719

8.. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China: N Engl J Med, 2020; 382; 1708-20

9.. Suwanwongse K, Shaberek N, Rhabdomyolysis as a presentation of 2019 novel coronavirus disease: Cureus, 2020; 12(4); e7561

10.. Jin M, Tong Q, Rhabdomyolysis as potential late complication associated with COVID-19: Emerg Infect Dis, 2020; 26(7); 1618-20

11.. Chedid NR, Udit S, Salhjou Z, COVID-19 and rhabdomyolysis: J Gen Int Med, 2020; 5(10); 3087-90

12.. Makaryus JN, Catanzaro JN, Katona KC, Exertional rhabdomyolysis and renal failure in patients with sickle cell traits: Is it time to change our approach?: Hematology, 2007; 12(4); 349-52

13.. Derebail VK, Nachman PH, Key NS, High prevalence of sickle cell trait in African Americans with ESRD: J Am Soc Nephrol, 2010; 21(3); 413-17

14.. Kehinde TA, Osundiji MA, Sickle cell trait and the potential risk of severe coronavirus disease 2019 – a mini review: Eur J Haematol, 2020; 105; 519-23

15.. Tafty D, Kluckman M, Dearborn MC, COVID-19 in patients with hematologic-oncologic risk factors: Complications in three patients: Cureus, 2020; 12(12); e12064

16.. Bergström J, Wehle B, No change in corrected beta 2-microglobulin concentration after cuprophane haemodialysis: Lancet, 1987; 1(8533); 628-29

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Patient’s daily laboratory values.

Table 1.. Patient’s daily laboratory values. Table 2.. Reduction rates per session (RRs,%) of laboratory parameters during HFR-Supra H dialysis.

Table 2.. Reduction rates per session (RRs,%) of laboratory parameters during HFR-Supra H dialysis. Table 3.. Previous reports of SARS-CoV-2 infection associated with rhabdomyolysis.

Table 3.. Previous reports of SARS-CoV-2 infection associated with rhabdomyolysis. Table 1.. Patient’s daily laboratory values.

Table 1.. Patient’s daily laboratory values. Table 2.. Reduction rates per session (RRs,%) of laboratory parameters during HFR-Supra H dialysis.

Table 2.. Reduction rates per session (RRs,%) of laboratory parameters during HFR-Supra H dialysis. Table 3.. Previous reports of SARS-CoV-2 infection associated with rhabdomyolysis.

Table 3.. Previous reports of SARS-CoV-2 infection associated with rhabdomyolysis. In Press

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942826

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942770

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943214

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943010

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250