14 April 2022: Articles

Waterhouse-Friderichsen Syndrome with Bilateral Adrenal Hemorrhage Associated with Methicillin-Resistant (MRSA) Bacteremia in an Adult Patient with History of Intravenous Drug Use

Unusual clinical course, Rare disease, Educational Purpose (only if useful for a systematic review or synthesis)

Thomas Kalinoski1EF*DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.936096

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936096

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome, also known as acute adrenal insufficiency due to adrenal gland hemorrhage, is an uncommon and frequently fatal condition classically presenting with fever, shock, rash, and coagulopathy. Although most often associated with Meningococcemia, many other etiologies have been implicated, including reports of Staphylococcus aureus infection on autopsy examinations. This report details an adult intravenous drug user with adrenal hemorrhage associated with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia.

CASE REPORT: A 58-year-old man with a history of intravenous drug use presented to the hospital with weakness. Vitals were initially normal and exam findings were notable for decreased right-sided motor strength. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a cervical epidural abscess with spinal cord compression. Despite initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics and intravenous fluids, the patient progressed to shock, requiring vasopressor administration, and his blood cultures later grew MRSA. Further imaging of the abdomen/pelvis was completed, revealing bilateral adrenal hemorrhage. Random cortisol at that time was 5.6 µg/dL, confirming a diagnosis of critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency in addition to likely septic and spinal shock. The patient was initiated on hydrocortisone with improvement in his hypotension. He was transitioned to prednisone and fludrocortisone in addition to 8 weeks of antibiotics after achieving clinical stability.

CONCLUSIONS: This report brings to attention the risk of adrenal hemorrhage and acute adrenal insufficiency as a sequela of the relatively common illness of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. As symptoms of adrenal insufficiency can overlap with septic shock related to the primary condition, this diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion in the critically ill patient.

Keywords: adrenal insufficiency, Bacteremia, Waterhouse-Friderichsen Syndrome, Adrenal Gland Diseases, Adult, Anti-Bacterial Agents, Hemorrhage, Humans, Male, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcal Infections, Substance Abuse, Intravenous

Background

Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome describes the phenomenon of acute adrenal insufficiency in the setting of bilateral adrenal hemorrhage, originally defined in the setting of

Despite being one of the leading causes of bloodstream infections, the organism

The first of these case series involved a postmortem examination of 800 cases of septic shock in children and adults. Ultimately, 5 of the specimens were found to reveal adrenal hemorrhage. Two of those 5 patients (1 child and 1 adult) had either pre- or postmortem cultures growing

Another case series that involved both children and adults who died of fatal bacterial infection, with 65 specimens sent to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) found 4 cases of bilateral adrenal hemorrhage in patients with

An additional study described 3 children with

Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage was discovered on autopsy in all cases. One of the patients had been diagnosed with

The final publication is a case report of a 7-year-old boy with methicillin-sensitive

The present report is of a 58-year-old man with a history of intravenous (i.v.) drug use with adrenal hemorrhage and Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome associated with methicillin-resistant

Case Report

A 58-year-old man with a history of alcohol and methamphetamine use disorders and hypertension was brought into the emergency room by ambulance with right-sided weakness resulting in a ground-level fall. The patient described weakness in the right upper and lower extremities, which had resulted in difficulty walking. The weakness resulted in him falling onto his back and hitting his head without losing consciousness. The patient denied numbness, bowel or bladder incontinence, or other neurological symptoms. He endorsed recent shortness of breath but no cough, fevers, or rash. A complete review of symptoms was otherwise normal. The patient did endorse i.v. drug use with methamphetamine and recently fentanyl. He was not taking any anticoagulant medications.

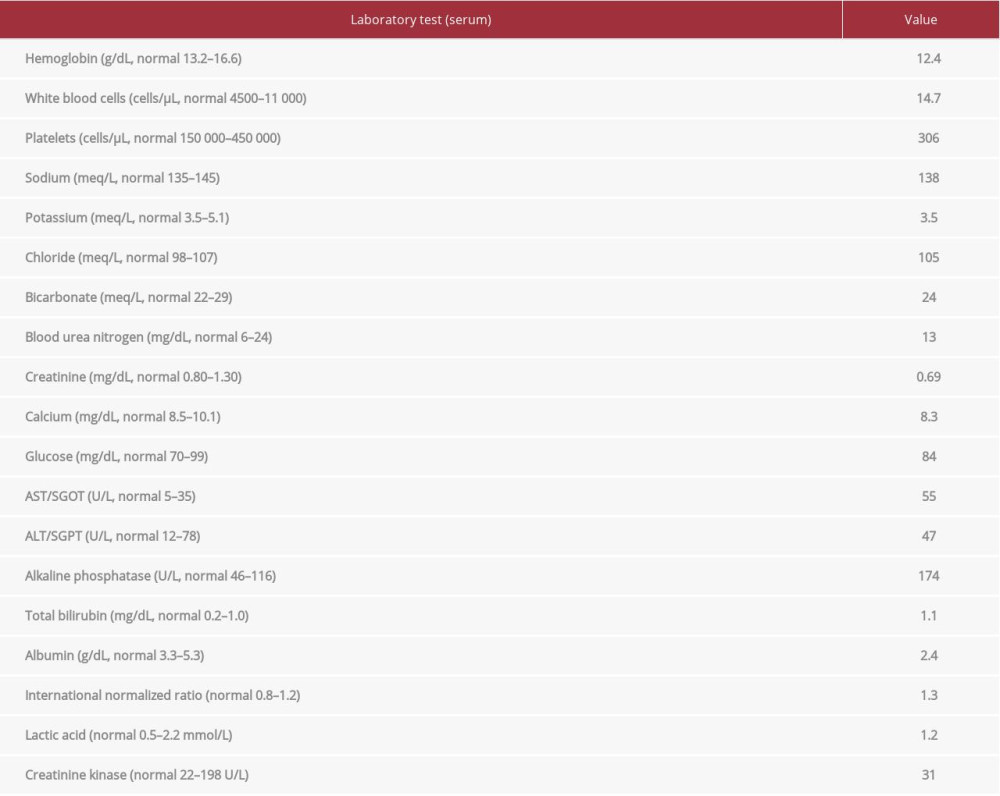

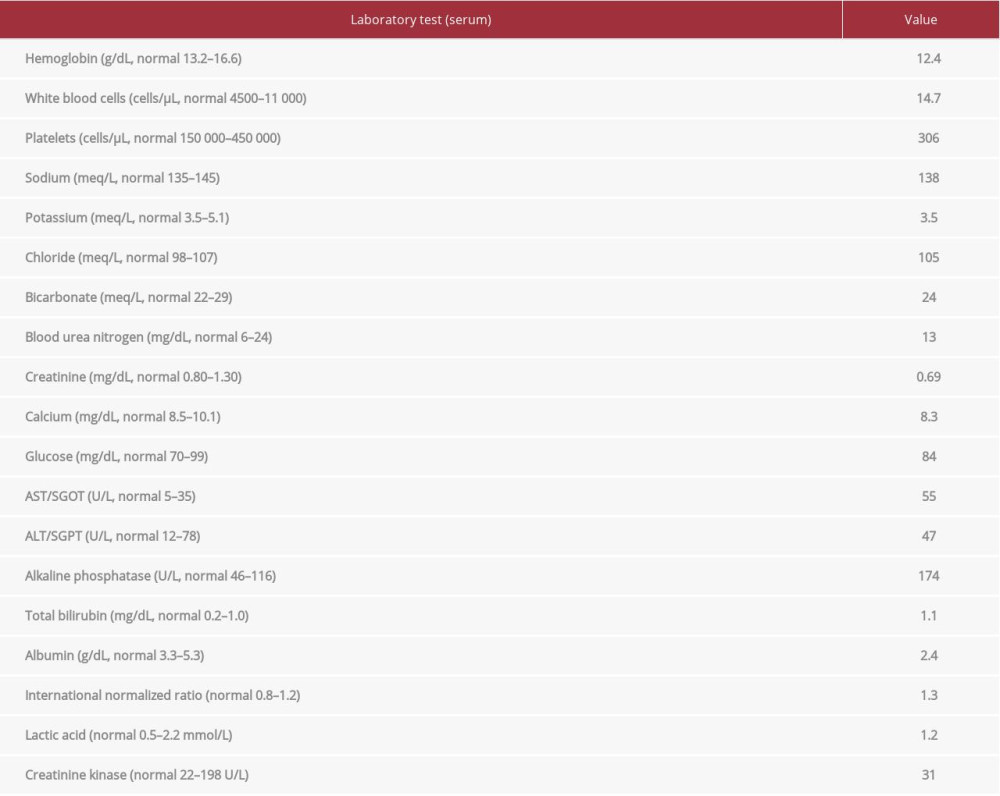

On presentation, the patient’s blood pressure was 111/62, pulse 102 beats/minute, respirations 20/minute, peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) 95% on room air, and temperature 38.4°C. The examination was remarkable for scattered bruising and track marks without a rash or frank purpura. No murmurs or crackles were appreciated. He was noted to have cervical spine tenderness to palpation. Strength in the right upper and lower extremity was 3/5, and strength elsewhere was 5/5. Reflexes were diminished globally. Gait testing was not possible due to the degree of weakness. The patient was alert but oriented to only self and place. The rest of the neurological exam, including cranial nerves, sensation, and cerebellar function, was normal. Initial laboratory studies were remarkable for a white blood count of 14 700/µL with 87% neutrophils. The platelets were 306 000/µL and hemoglobin was 12.4 g/dL. International normalized ratio (INR) was 1.3. Electrolytes, kidney and liver function tests, bilirubin, lactate, and creatine kinase were normal (Table 2). Blood cultures were drawn at that time.

Other pertinent diagnostic studies include a negative sputum culture, interferon gamma release assay (IGRA), human immune deficiency virus (HIV) serology, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) nucleic acid test, cryptococcal antigen, aspergillus serology and galactomannan antigen, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, and coccidioides serology, 1,3-beta-d-glucan, and legionella urine antigen. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), and antinuclear antibodies (ANA) were all unrevealing. An electrocardiogram was normal. Computed tomography (CT) of the head and cervical spine were normal, but magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and complete spine revealed findings consistent with discitis, osteomyelitis, and epidural abscess with spinal cord compression at C5–C6. CT imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed upper-lobe cavitary nodules and bilateral non-enhancing adrenal masses without calcification, consistent with acute adrenal hemorrhage (Figure 1) [18].

The patient was administered broad-spectrum antibiotics, including vancomycin, as well as i.v. fluids. Despite this, his clinical status declined rapidly with hypotension and shock, acute encephalopathy, worsened weakness to include his left upper and lower extremities, with loss of sensation below the clavicle bilaterally, and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. The patient was intubated due to respiratory status and for airway protection and initiated on vasopressor medications. His blood cultures drawn on admission at that time revealed 2/2 bottles positive for gram-positive cocci in clusters

Overall gains were made in clinical status over the next few days, with blood cultures clearing and improvements in respiratory and mental status to the point of extubation. The patient’s hypotension persisted for much longer, however, initially requiring 2 pressors on admission. The patient was additionally started on i.v. hydrocortisone 50 mg every 8 h 3 days later after the above CT findings and an 08: 00 a.m. serum cortisol measurement of 5.6 µ/dL. Hydrocortisone was continued at the stated dose for 5 days, then slowly tapered and transitioned to prednisone and fludrocortisone. This treatment corresponded with an improvement in blood pressure over the next several days, although the patient still required norepinephrine off and on. As clinical evidence pointed towards resolution of the septic shock and the adrenal insufficiency was being treated, a component of neurogenic shock from the spinal cord injury was considered and the patient was transitioned to long-term midodrine. Although unfortunately not recovering motor function, the patient remained stable for the remainder of his hospital course and completed 8 weeks of i.v. antibiotics for MRSA bacteremia and presumed endocarditis.

Discussion

The case presented above brings to attention several learning points for clinicians. The first of these is to be aware of the possibility of acute adrenal hemorrhage and adrenal insufficiency as an etiology of refractory shock in

In our patient,

General measures for the treatment of sepsis and Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome were provided, including prompt antibiotic therapy, i.v. fluids, vasopressors, and hydrocortisone therapy. Our patient’s shock improved only after initiation of hydrocortisone therapy, although he did still need long-term midodrine for a component of spinal shock from his cervical cord injury. Although our patient survived the illness with severe resultant morbidity, all other referenced patients died as a result of their illness [13–16]. This compares to a mortality rate of 15–50% for Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome as a whole [1–2].

Interestingly, our patient did not develop the rash and coagulopathy characteristic of classic meningococcal Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome. Although variably present, especially in non-meningococcal infections, these features were in fact reported in all published cases of

Similar to meningococcal infection, the majority of the known published cases of

Conclusions

This paper emphasizes the uncommon sequela of Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome associated with

References:

1.. Karki BR, Sedhai YR, Rizwan S, Bokhari A, Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome: StatPearls; 1(1) [serial online]. 2021 Dec [cited 2021 Dec 30];

2.. Varon J, Chen K, Sternbach G, Rupert Waterhouse and Carl Friderichsen: Adrenal apoplexy: J Emerg Med, 1998; 16(4); 643-47

3.. Wu MY, Chen CS, Tsay CY, Neisseria meningitidis induced fatal Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome in a patient presenting with disseminated intravascular coagulation and multiple organ failure: Brain Sci, 2020; 10(3); 171

4.. Carvalho R, Henriques F, Teixeira S, Coimbra P: BMJ Case Rep, 2021; 14(2); e238670

5.. Sonavane A, Baradkar V, Salunkhe P, Kumar S, Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome in an adult patient with meningococcal meningitis: Indian J Dermatol, 2011; 56(3); 326-28

6.. Doherty S, Fatal pneumococcal Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome: Emerg Med, 2001; 13(2); 237-39

7.. Hale AJ, LaSalvia M, Kirby J: IDCases, 2016; 6; 1-4

8.. Hamilton D, Harris MD, Foweraker J, Gresham GA, Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome as a result of non-meningococcal infection: J Clin Pathol, 2004; 57(2); 208-9

9.. Chiwome L, A rare case of Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome without purpura secondary to Haemophilus influenzae: Cureus, 2020; 12(8); e9621

10.. Morrison U, Taylor M, Sheahan DG, Keane CT, Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome without purpura due to Haemophilus influenzae group B: Postgrad Med J, 1985; 61(711); 67-68

11.. Khwaja J: J Med Case Rep, 2017; 11; 72

12.. Ventura Spagnolo E, Mondello C, Roccuzzo S: Medicine (Baltimore), 2019; 98(34); e16664

13.. Tormos LM, Schandl CA, The significance of adrenal hemorrhage: Undiagnosed Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome, a case series: J Forensic Sci, 2013; 58(4); 1071-74

14.. Guarner J, Paddock CD, Bartlett J, Zaki SR, Adrenal gland hemorrhage in patients with fatal bacterial infections: Mod Pathol, 2008; 21(9); 1113-20

15.. Adem PV, Montgomery CP, Husain AN: N Engl J Med, 2005; 353(12); 1245-51

16.. Mukherjee D, Prasun Giri P, Poddar S, Waterhouse Friderichsen syndrome in a case of staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome: J Pediatr Crit Care, 2016; 2; 52-54

17.. Cosgrove SE, Fowler VG: Clin Infect Dis, 2008; 46(5); S386-93

18.. Jordan E, Poder L, Courtier J, Imaging of nontraumatic adrenal hemorrhage: Am J Roentgenol, 2012; 191(1); 91-98

19.. Annane D, Pastores SM, Rochwerg B, Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency (CIRCI) in critically ill patients (part I): Society of critical care medicine (SCCM) and European society of intensive care medicine (ESICM) 2017: Crit Care Med, 2017; 45(12); 2078-88

Tables

Table 1.. Comparison of clinical characteristics of published cases involving Staphylococcus aureus-associated adrenal hemorrhage.

Table 1.. Comparison of clinical characteristics of published cases involving Staphylococcus aureus-associated adrenal hemorrhage. Table 2.. Relevant laboratory profile of the patient at the time of presentation.

Table 2.. Relevant laboratory profile of the patient at the time of presentation. Table 1.. Comparison of clinical characteristics of published cases involving Staphylococcus aureus-associated adrenal hemorrhage.

Table 1.. Comparison of clinical characteristics of published cases involving Staphylococcus aureus-associated adrenal hemorrhage. Table 2.. Relevant laboratory profile of the patient at the time of presentation.

Table 2.. Relevant laboratory profile of the patient at the time of presentation. In Press

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943042

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942578

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943801

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942966

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250