22 October 2022: Articles

Association Between Parafibromin Expression and Presence of Brown Tumors and Jaw Tumors in Patients with Primary Hyperparathyroidism: Series of Cases with Review of the Literature

Challenging differential diagnosis, Unusual setting of medical care, Rare disease, Congenital defects / diseases, Educational Purpose (only if useful for a systematic review or synthesis), Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Michał Popow1ABCDEF, Monika Kaszczewska12ABCDEF, Magdalena Góralska1BCD, Piotr Kaszczewski2BCDEF*, Agata Skwarek-SzewczykDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.936135

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936135

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Brown and jaw tumors are rare entities of poorly understood etiology that are regarded as end-stage of bone remodeling in patients with long-lasting and chronic hyperparathyroidism. Jaw tumors are mainly diagnosed in jaw tumors syndrome (HPT-JT syndrome) and are caused by mutation in the CDC73 gene, encoding parafibromin, a tumor suppressing protein. The aim of this work is to present 4 cases of patients in whom the genetic mutation of the CDC73 gene and clinical presentation coexist in an unusual setting that has not yet been described.

CASE REPORT: We present cases of 4 patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Three were diagnosed with brown tumors (located in long bones, ribs, iliac, shoulders) and 1 with brown and jaw tumors. Expression of parafibromin in affected parathyroid tissues were analyzed. In patients without positive parafibromin staining, we searched for CDC73 mutation using next-generation sequencing. Parafibromin staining was positive in 1 patient with brown tumors and was negative in 2 individuals with brown tumors and 1 with brown and jaw tumors. CDC73 mutation was detected in two-thirds of patients (60%) with negative staining for parafibromin and brown tumors. MEN1 mutation was found in the patient with brown tumor and positive staining for parafibromin.

CONCLUSIONS: Patients with hyperparathyroidism and coexistence of brown tumors or jaw tumors might have decreased expression of parafibromin in parathyroid adenoma tissue, which might be caused by CDC73 mutation and suggest a genetic predisposition. Further research on much larger study groups is needed.

Keywords: CDC73 Protein, Human, Hedgehogs, Hyperparathyroidism, Humans, Hyperparathyroidism, Primary, Tumor Suppressor Proteins, Jaw Neoplasms, Parathyroid Neoplasms, Fibroma, Transcription Factors

Background

Primary hyperparathyroidism is one of the most common endocrinopathies, with a prevalence of up to 1.1% in Europe. About 80% of cases involve a single adenoma arising as a result of a mutation or loss of heterozygosity in the nucleus of a single parathyroid cell [1,2]. The other 20% of cases result from congenital mutations in all nucleated cells [3–7].

Bone tumors are very rare entities that can coexist with prolonged primary hyperparathyroidism. They are believed to represent the end-stage of the bone remodeling process. One type is the jaw tumor, which, in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism, is known as hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor (HPT-JT) syndrome. It is caused by mutation in the

Mutations in the

The role of parafibromin is important and complex. The connection with the Wnt, NOTCH, and Hedgehog (Hh) pathways indicates its role in embryogenesis, in the regulation of gene expression, and in carcinogenesis, in which the Wnt and Hh pathways are closely related to this process and the inhibition of oncogenesis (the role of parafibromin is poorly understood in this process) [38–44].

In an animal model, a 50% reduction in the expression of the C fragment of the final parafibromin did not stimulate carcinogenesis. This may indicate a correlation between uncontrolled cell proliferation within the N-terminal fragment and its effect on the regulation of the Wnt-NOTCH-Hh pathways. A comparison of immunohistochemical tests in adenomas and parathyroid carcinomas revealed no differences in the expression of Wnt/Hh pathway components interacting with parafibromin [45].

Within the parafibromin molecule, 3 binding sites of the entire nuclear localization signal (NLS) have been located. The first seems to play a key role (position 125–139), the second a supportive role (position 76–92), and the third, which is within the final fragment C (position 393–409), is probably involved in the activation of the polymerase I-associated factor (PAF1) enzymatic complex due to homology with the primary molecule Cdc73 found in yeast [46].

The nuclear attachment sites of parafibromin determine its regulatory effect on cell proliferation. Therefore, the intact molecule is necessary not only to create a scaffold for the PAF1 enzymatic complex and the Wnt-NOTCH-Hh metabolic pathways, but also to attach the entire complex to the cell nucleus. Leucine-rich fragments of parafibromin may also function as sequences necessary for transport from the cytoplasm to the nuclear export sequences of the nucleus, but its exact location has not been determined [46,47].

In this study, we wanted to determine whether the presence of brown tumors with or without lesions in the jaw or maxilla can be associated with abnormal parafibromin expression or

Case Reports

PATIENT SELECTION CRITERIA:

The inclusion criteria were (1) clinical and biochemical symptoms of primary hyperparathyroidism and (2) presence of brown tumor or jaw tumor confirmed by MIBI SPECT/CT.

The exclusion criteria were (1) secondary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism; (2) malabsorption (eg, celiac disease); (3) previous bariatric surgery; (4) renal failure (eGFR <60 mL/min./1.73m2); (5) parathyroid hormone (PTH)-independent hypercalcemia; and (6) malignant diseases with metastatic bone lesions.

PATIENT 1:

A 57-year-old man, who was diagnosed with hyperparathyroidism at age of 29, presented with a history of nephrolithiasis, nephrocalcinosis, and 2 hypercalcemic crises in the course of an adenoma of the right upper parathyroid gland that was treated surgically in 1993 and an adenoma of the left lower parathyroid gland that was treated surgically in 2013. The patient did not report a history of smoking, alcohol use, or substance abuse. In the course of making the differential diagnosis, brown tumors in the right humerus and both tibias were found. The patient’s main medical problem was recurrent hyperparathyroidism along with nephrocalcinosis, recurrent nephrolithiasis, brown tumors, and osteoporosis. He had an increasing proliferation index of parathyroid cells (2% in 1993, 7.3% in 2013). The patient had coexisting kidney cysts and hypertension. His medications were vitamin D 2000 units daily, amlodipine 10 mg daily, and alendronate sodium 70 mg once a week.

The following tests were performed. An imaging examination was done with MIBI SPECT/CT. Immunohistochemical staining and genetic tests were conducted following the parathyroidectomy. The removed parathyroid glands were stained against parafibromin using immunohistochemical methods, anti-parafibromin mouse monoclonal antibody, primary parafibromin antibody, and secondary antibody. Subsequently, genetic tests were performed for mutations in the following genes:

Parafibromin staining was negative within the cell nuclei. A very weak cytoplasmic expression of parafibromin was observed. In genetic testing, a

The summary of the clinical problem was a genetically determined form of primary hyperparathyroidism in the course of mutation of the CDC73 gene encoding the parafibromin protein.

PATIENT 2:

A 42-year-old White man who was diagnosed with hyperparathyroidism at the age of 36 years and had a medical history of nephrolithiasis, recurrent cysts of long bones (resection of the left fifth metacarpal bone cyst in November 2014), osteopenia, brown tumors, kidney cysts, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was admitted to the Endocrinology Department owing to the persistence of high calcium and PTH levels. The patient received 1000 units vitamin D per day. The patient reported a history of smoking (20 cigarettes per day) and no alcohol or other substance abuse.

In a SPECT/CT examination, a lesion of the left lower parathyroid gland with a possible infiltration of the sternothyroid muscle was diagnosed. Because of the suspicion of a proliferative process, the patient was urgently referred for surgical treatment. Following the parathyroidectomy, immunohistochemical staining and genetic tests were conducted. The removed parathyroid glands were stained against parafibromin using immunohistochemical methods, anti-parafibromin mouse monoclonal antibody, primary parafibromin antibody, and secondary antibody. Subsequently, genetic tests were performed for mutations in the following genes:

Very weak nuclear expression of parafibromin (intensity score <1) with negative cytoplasmatic staining were observed. The proliferation index of parathyroid cells was 1.5%. In genetic testing, the

The summary of the clinical problem was a genetically determined form of primary hyperparathyroidism in the course of mutation of the CDC73 gene encoding the parafibromin protein.

PATIENT 3:

A 45-year-old White woman who was first diagnosed with hyperparathyroidism at the age of 36 years and who had congenital craniofacial development disorder and eyeball hypoplasia, an 8-year history of nephrolithiasis (that was treated with extracorporal shockwave lithotripsy), complicated by ureteral stenosis and secondary hydronephrosis (that was also treated surgically in 2014), thrombosis of the iliac veins and inferior vena cava, uterine fibroids, left ovary cyst and spleen cysts, colon polyps, and very low level of vitamin D (<3 ng/dL) was referred to the Endocrinology Department because of uncontrolled hyperparathyroidism. The patient was taking enoxaparin 60 mg twice a day. In the course of the diagnostic process, multiple brown tumors of the long, flat bones, mandible, and maxilla were found. During hospitalization, the patient had a transverse fracture of the right femur, which occurred while changing the position of the body. It was fracture in the site of the brown tumor and a pathological fracture of the left patella.

In a SPECT/CT examination, a 3-cm lesion of the right lower parathyroid gland was diagnosed, and the patient was referred for surgery. Following the parathyroidectomy, the removed parathyroid glands were stained against parafibromin using immunohistochemical methods, anti-parafibromin mouse monoclonal antibody, primary parafibromin antibody, and secondary antibody. Subsequently, genetic testing was performed for mutations in the following genes:

Parafibromin staining within the cell nuclei was negative. No mutations were detected within the

The summary of the clinical problem was that because of the clinical features of the HPT-JT syndrome, a test for mutation of the

PATIENT 4:

A 42-year-old White man who was first diagnosed with hyper-parathyroididsm at the age of 30 years and who had severe skeletal deformities was referred to the Endocrinology Department owing to hypercalcemic crisis secondary to hyperparathyroidism. The patient’s concomitant disorders were non-secreting neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas, macroprolactinoma, and pituitary insufficiency. His previous medical history included nephrolithiasis, complicated with hydronephrosis. The patient reported no history of smoking, alcohol use, or substance abuse. He was taking levothyroxine 75 ug and hydrocortisone 15 mg daily in selected doses, and Cabergoline 0.5 mg once a week. In the course of the diagnostic process, brown tumors in the long bones were detected. The presence of a focal lesion in the pancreas and pituitary microprolactinoma resulted in suspicion of MEN1 or MEN4 syndrome. Because of fulfilling the diagnostic criteria of MEN syndrome, the patient was referred for a subtotal parathyroidectomy. Immunohistochemical staining and genetic tests were conducted following the parathyroidectomy. The removed parathyroid glands were stained against parafibromin using immunohistochemical methods, anti-parafibromin mouse monoclonal antibody, primary parafibromin antibody, and secondary antibody. Positive staining in the nucleus and cytoplasm was detected.

Subsequently, genetic tests were performed for mutations in the following genes:

The summary of the clinical problem was that, in view of the clinical suspicion of MEN syndrome, tests for mutation of

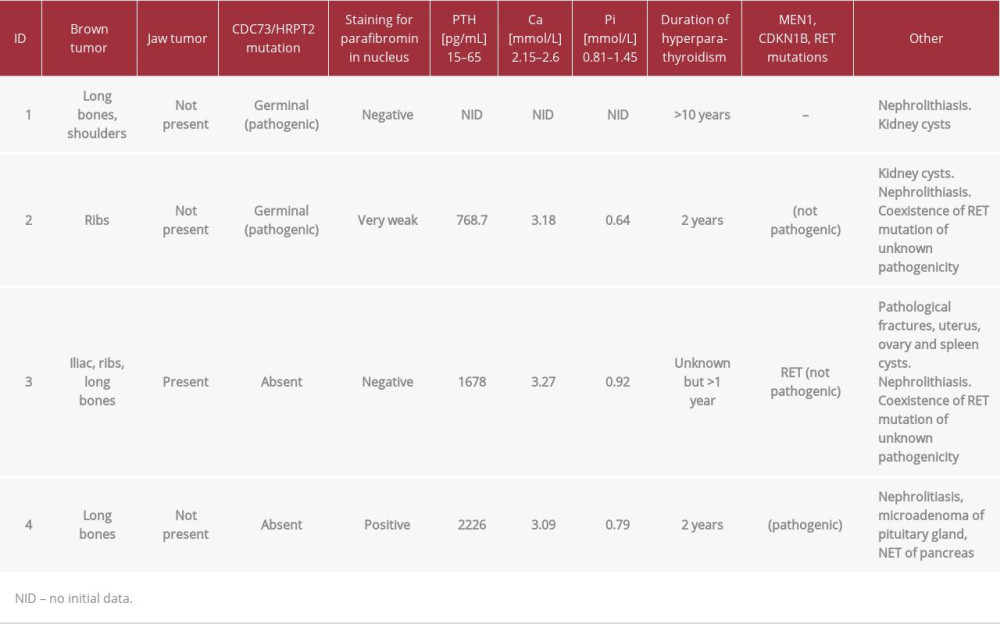

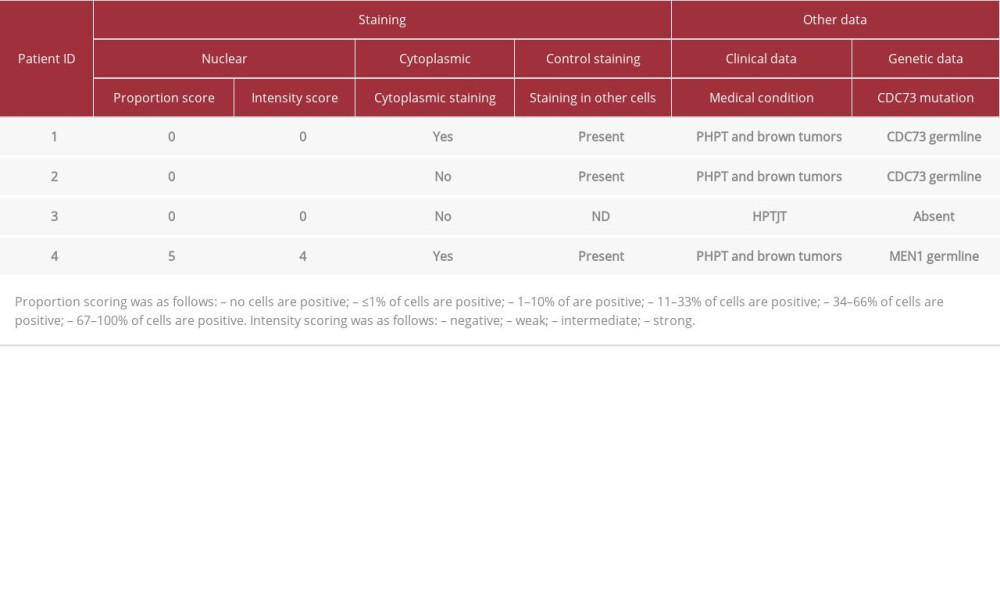

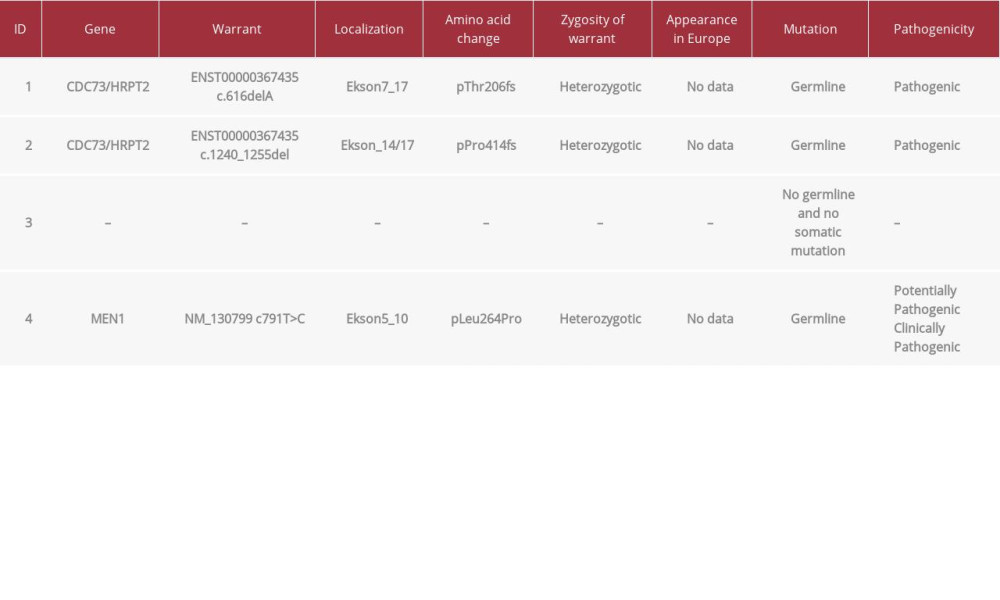

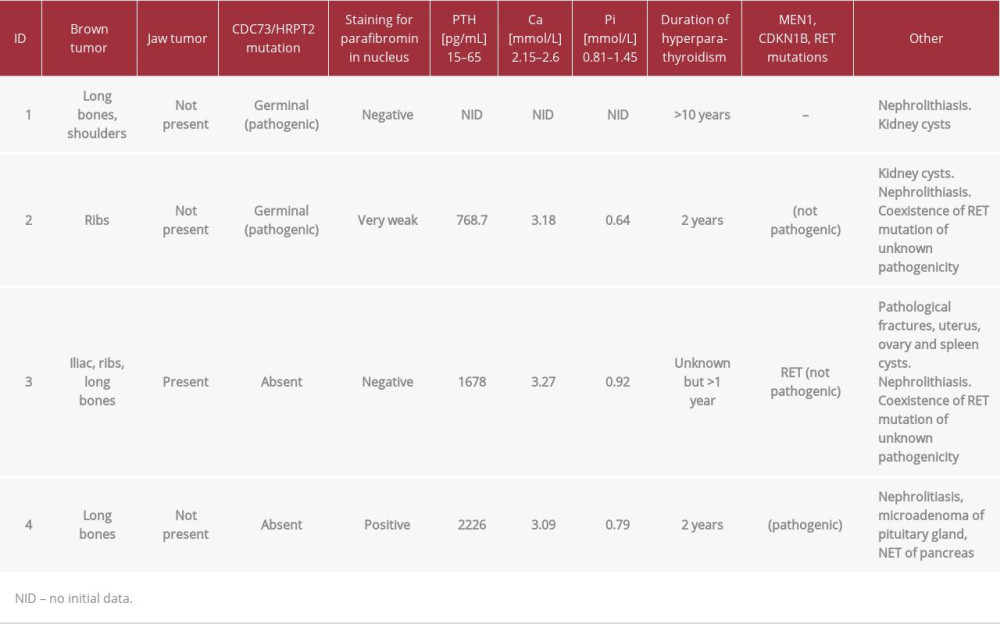

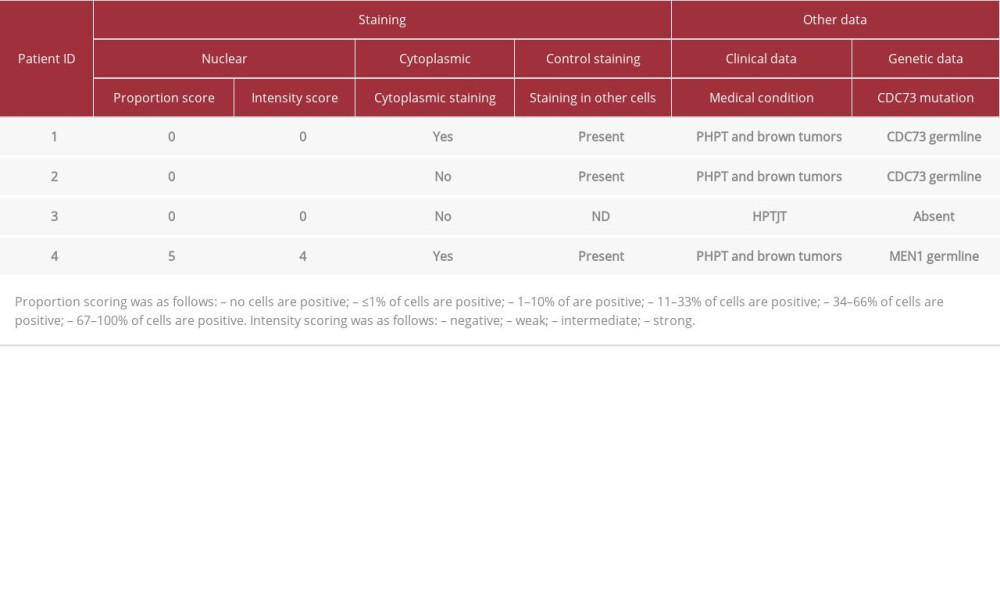

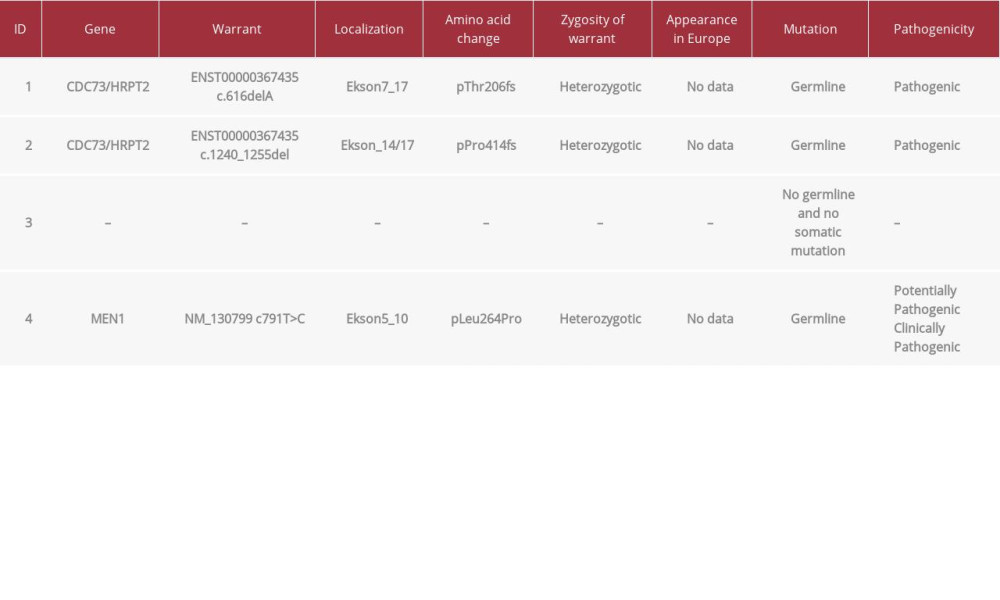

The samples of parafibromin staining for all patients are presented in Figure 1. The clinical features in the group of patients with brown/jaw tumors are presented in Table 1. The data concerning parafibromin staining and genetic tests in the study group are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Discussion

Today, due to the common screening of calcium levels in out-patient clinics, brown tumors are rarely observed, except for in patients with HPT-JT syndrome, which is caused by a mutation of the

In our study, we presented 4 cases of patients in whom the genetic mutation of the

In our patients, genetic testing and parafibromin staining were performed. The complete coding sequence of the

Genetic testing enabled not only confirmation of the presence of the

Pathogenic mutations of the

In patient 1, transcription was inhibited in the 616th nucleotide. This caused protein synthesis to stop at the point of 202 amino acids, resulting in loss of the C-terminal fragment. From a clinical point of view, this is due to the inability of attachment of the PAF2 enzyme complex to the cell nucleus within the conservative NLS (393–409). In spite of having other NLS, staining of parathyroid cells obtained from parafibromin histopathological preparations showed that this protein was not present in the cell nucleus. At the same time, staining in the cytoplasm was observed, which may suggest loss of the nuclear export sequence site responsible for the transport of parafibromin from the cytoplasm into the cell nucleus.

In patient 2, protein synthesis was stopped at the point of 414 amino acids, which was caused by deletion of the 14/17 exon on the

In the case of the classic form of HPT-JT syndrome in patient 3, there was no

Patient 4 had positive staining for parafibromin in the probed parathyroid tissue. In 2 cases, the loss at least of 1 of the 3 attachment points to the cell nucleus and the binding site to the PAF1 polymerase complex was observed. The subsequent staining demonstrated the absence of parafibromin in the cell nucleus and presence in the cytoplasm. This may indicate that shortening the molecule to 202 amino acids results in the loss of the nuclear export sequence necessary to translocate this protein into the nucleus. Loss of the final C fragment, but with the NLS left intact, allowed for its attachment to the DNA strand, but in this case (patient 2), the staining was very weak.

Failure to detect the

The

In 1 patient, advanced bone changes and skeletal deformity with hyperparathyroidism and normal staining for parafibromin were detected. In this patient, mutation in the

Crosstalk between hyperparathyroidism, high expression of the

Due to the suspected association between an increased risk of the

Germinal mutation of

It has been proposed that parafibromin is an important modulator and regulator of gene expression dependent on the Hh-Wnt-NOTCH pathways [40–42]. We think that the change in protein structure can lead to dysregulation of the Wnt and Hh pathways and, through this mechanism, promote carcino-genesis. Our team suspects that patients with brown tumors may have a higher risk of the mutation of

We hope our study can be a driver toward discussion and cooperation leading to studies in a larger groups of patients, and that these studies derive stronger statistically and clinically significant conclusions.

Conclusions

In patients with brown tumors, a genetic etiology of the disease should be considered.

The association of parafibromin expression changes with malignancies (parathyroid, genitourinary system, lung, skin, and pancreas) can change the approach to such patients, who should be diagnosed more broadly than patients with classic primary hyperparathyroidism.

We hope our case study opens the discussion on the significance of brown tumors as a warning against the potential risk of parathyroid cancer or other malignant comorbidities.

Further research of the topic is necessary with multi-source cooperation and data collection.

Nuclear export sequence location for parafibromin has been proposed.

References:

1.. Falchetti A, Marini F, Giusti F, DNA-based test: When and why to apply it to primary hyperparathyroidism clinical phenotypes: J Intern Med, 2009; 266(1); 69-83

2.. Carling T, Molecular pathology of parathyroid tumors: Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2001; 12(2); 53-58

3.. Dwight T, Twigg S, Delbridge L, Loss of heterozygosity in sporadic parathyroid tumours: Involvement of chromosome 1 and the MEN1 gene locus in 11q13: Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 2000; 53(1); 85-92

4.. Borsari S, Pardi E, Pellegata NS, Loss of p27 expression is associated with MEN1 gene mutations in sporadic parathyroid adenomas: Endocrine, 2017; 55(2); 386-97

5.. Schernthaner-Reiter MH, Trivellin G, Stratakis CA, MEN1, MEN4, and carney complex: Pathology and molecular genetics: Neuroendocrinology, 2016; 103(1); 18-31

6.. Duan K, Mete Ö, Parathyroid carcinoma: Diagnosis and clinical implications: Turk Patoloji Derg, 2015; 31(Suppl. 1); 80-97

7.. Walls GV, Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes: Semin Pediatr Surg, 2014; 23(2); 96-101

8.. Boyce AM, Florenzano P, de Castro LF, Collins MT, Fibrous dysplasia/McCune-Albright Syndrome February 26, 2015, Seattle (WA), University of Washington Seattle

9.. de Mesquita Netto AC, Gomez RS, Diniz MG, Assessing the contribution of HRPT2 to the pathogenesis of jaw fibrous dysplasia, ossifying fibroma, and osteosarcoma: Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol, 2013; 115(3); 359-67

10.. Chen Y, Hu DY, Wang TT, CDC73 gene mutations in sporadic ossifying fibroma of the jaws: Diagn Pathol, 2016; 11(1); 91

11.. Misiorowski W, Czajka-Oraniec I, Kochman M, Osteitis fibrosa cystic – a forgotten radiological feature of primary hyperparathyroidism: Endocrine, 2017; 58(2); 380-85

12.. Ryhänen EM, Leijon H, Metso S, A nationwide study on parathyroid carcinoma: Acta Oncol, 2017; 56(7); 991-1003

13.. Ouzaa MR, Bennis A, Iken M, Primary hyperparathyroidism associated with a giant cell tumor: One case in the distal radius: Chir Main, 2015; 34(5); 260-63

14.. Sabanis N, Gavriilaki E, Paschou E, Rare skeletal complications in the setting of primary hyperparathyroidism: Case Rep Endocrinol, 2015; 2015; 139751

15.. Rossi B, Ferraresi V, Appetecchia ML, Giant cell tumor of bone in a patient with diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism: A challenge in differential diagnosis with brown tumor: Skeletal Radiol, 2014; 43(5); 693-97

16.. Guliaeva SS, Voloshchuk IN, Mokrysheva NG, Ia Rozhinskaia L, [Maldiagnosis of giant-cell tumor of the bone in a patient with hyperparathyroid osteo-dystrophy.]: Arkh Patol, 2009; 71(5); 53-55 [in Russian]

17.. Mavrogenis AF, Igoumenou VG, Megaloikonomos PD, Giant cell tumor of bone revisited: SICOT J, 2017; 3; 54

18.. Pezzillo F, Di Matteo R, Liuzza F, Isolated bone lesion secondary to hyperparathyroidism: diagnostic considerations: Clin Ter, 2008; 159(4); 265-68

19.. Yang Q, Sun P, Li J, Skeletal lesions in primary hyperparathyroidism: Am J Med Sci, 2015; 349(4); 321-27

20.. Hosny Mohammed K, Siddiqui MT, Willis BC, Parafibromin, APC, and MIB-1 are useful markers for distinguishing parathyroid carcinomas from adenomas: Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol, 2017; 25(10); 731-35

21.. Verdelli C, Corbetta S, Epigenetic alterations in parathyroid cancers: Int J Mol Sci, 2017; 18(2); 310

22.. Yart A, Gstaiger M, Wirbelauer C, The HRPT2 tumor suppressor gene product parafibromin associates with human PAF1 and RNA polymerase II: Mol Cell Biol, 2005; 25(12); 5052-60

23.. Newey PJ, Bowl MR, Thakker RV, Parafibromin – functional insights: J Intern Med, 2009; 266(1); 84-98

24.. Hattangady NG, Wilson TL, Miller BS, Recurrent hyperparathyroidism due to a novel CDC73 splice mutation: J Bone Miner Res, 2017; 32(8); 1640-43

25.. Cho I, Lee M, Lim S, Hong R, Significance of parafibromin expression in laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas: J Pathol Transl Med, 2016; 50(4); 264-69

26.. Zheng HC, Wei ZL, Xu XY, Parafibromin expression is an independent prognostic factor for colorectal carcinomas: Hum Pathol, 2011; 42(8); 1089-102

27.. Karaarslan S, Yaman B, Ozturk H, Kumbaraci BS, Parafibromin staining characteristics in urothelial carcinomas and relationship with prognostic parameters: J Pathol Transl Med, 2015; 49(5); 389-95

28.. Zheng HC, Takahashi H, Li XH, Downregulated parafibromin expression is a promising marker for pathogenesis, invasion, metastasis and prognosis of gastric carcinomas: Virchows Arch, 2008; 452(2); 147-55

29.. Parfitt J, Harris M, Wright JM, Kalamchi S, Tumor suppressor gene mutation in a patient with a history of hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor syndrome and healed generalized osteitis fibrosa cystica: A case report and genetic pathophysiology review: J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 2015; 73(1); 194.e1-9

30.. Hattangady NG, Wilson TL, Miller BS, Recurrent hyperparathyroidism due to a novel CDC73 splice mutation: J Bone Miner Res, 2017; 32(8); 1640-43

31.. Tahara H, Smith AP, Gaz RD, Parathyroid tumor suppressor on 1p: Analysis of the p18 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor gene as a candidate: J Bone Miner Res, 1997; 12(9); 1330-34

32.. Lin L, Zhang JH, Panicker LM, Simonds WF, The parafibromin tumor suppressor protein inhibits cell proliferation by repression of the c-myc protooncogene: Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2008; 105(45); 17420-25

33.. Zhang C, Kong D, Tan MH, Parafibromin inhibits cancer cell growth and causes G1 phase arrest: Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2006; 350(1); 17-24

34.. Zhao J, Yart A, Frigerio S, Sporadic human renal tumors display frequent allelic imbalances and novel mutations of the HRPT2 gene: Oncogene, 2007; 26(23); 3440-49

35.. Johnson ML, Recker RR, Exploiting the WNT signaling pathway for clinical purposes: Curr Osteoporos Rep, 2017; 15(3); 153-61

36.. Zanotti S, Canalis E, Notch signaling and the skeleton: Endocr Rev, 2016; 37(3); 223-53

37.. Lin L, Czapiga M, Nini L, Nuclear localization of the parafibromin tumor suppressor protein implicated in the hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor syndrome enhances its proapoptotic function: Mol Cancer Res, 2007; 5(2); 183-93

38.. Nuñez G, Benedict MA, Hu Y, Inohara N, Caspases: The proteases of the apoptotic pathway: Oncogene, 1998; 17(25); 3237-45

39.. Kumar S, Regulation of caspase activation in apoptosis: Implications in pathogenesis and treatment of disease: Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol, 1999; 26(4); 295-303

40.. Kikuchi I, Takahashi-Kanemitsu A, Sakiyama N, Dephosphorylated parafibromin is a transcriptional coactivator of the Wnt/Hedgehog/Notch pathways: Nat Commun, 2016; 7; 12887

41.. Mosimann C, Hausmann G, Basler K, Parafibromin/Hyrax activates Wnt/Wg target gene transcription by direct association with beta-catenin/Armadillo: Cell, 2006; 125(2); 327-41

42.. Mosimann C, Hausmann G, Basler K, The role of Parafibromin/Hyrax as a nuclear Gli/Ci-interacting protein in Hedgehog target gene control: Mech Dev, 2009; 126(5–6); 394-405

43.. Gu D, Xie J, Non-canonical Hh signaling in cancer-current understanding and future directions: Cancers (Basel), 2015; 7(3); 1684-98

44.. Katoh M, Canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling in cancer stem cells and their niches: Cellular heterogeneity, omics reprogramming, targeted therapy and tumor plasticity (review): Int J Oncol, 2017; 51(5); 1357-69

45.. Erovic BM, Harris L, Jamali M, Biomarkers of parathyroid carcinoma: Endocr Pathol, 2012; 23(4); 221-31

46.. Hahn MA, Marsh DJ, Identification of a functional bipartite nuclear localization signal in the tumor suppressor parafibromin [published correction appears in Oncogene. 2007;26(5):788]: Oncogene, 2005; 24(41); 6241-48

47.. Zhu JJ, Cui Y, Cui K, Distinct roles of parafibromin in the extracellular environment, cytoplasm and nucleus of osteosarcoma cells: Am J Transl Res, 2016; 8(5); 2426-31

49.. Juhlin CC, Nilsson IL, Lagerstedt-Robinson K, Parafibromin immunostainings of parathyroid tumors in clinical routine: A near-decade experience from a tertiary center: Mod Pathol, 2019; 32(8); 1082-94

49.. Rather MI, Swamy S, Gopinath KS, Kumar A, Transcriptional repression of tumor suppressor CDC73, encoding an RNA polymerase II interactor, by Wilms tumor 1 protein (WT1) promotes cell proliferation: Implication for cancer therapeutics: J Biol Chem, 2014; 289(2); 968-76

Tables

Table 1.. Clinical features in group of patients with brown and jaw tumors.

Table 1.. Clinical features in group of patients with brown and jaw tumors. Table 2.. Results of the staining against parafibromin and selected clinical features of the patients.

Table 2.. Results of the staining against parafibromin and selected clinical features of the patients. Table 3.. Results of genetic testing.

Table 3.. Results of genetic testing. Table 1.. Clinical features in group of patients with brown and jaw tumors.

Table 1.. Clinical features in group of patients with brown and jaw tumors. Table 2.. Results of the staining against parafibromin and selected clinical features of the patients.

Table 2.. Results of the staining against parafibromin and selected clinical features of the patients. Table 3.. Results of genetic testing.

Table 3.. Results of genetic testing. In Press

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942966

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942032

06 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942937

12 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943244

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250