14 July 2022: Articles

Lumbar Spinal Epidural Capillary Hemangioma: A Case Report and Literature Review

Mistake in diagnosis, Rare disease, Educational Purpose (only if useful for a systematic review or synthesis)

Shiying Wu1BCDEF*, Krishan Kumar Sharma2B, Chi Long Ho1345ABCDEFDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.936181

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936181

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Capillary hemangiomas are often seen on the skin of young individuals and are rarely found in the spine. These vascular lesions can arise from any spinal compartment, although they are more commonly found in the intradural extramedullary (IDEM) than the epidural location. We present a unique case of a woman with a histologically proven spinal epidural capillary hemangioma (SECH). The imaging and histopathological characteristics, as well as the treatment strategy of this vascular lesion, are highlighted along with a comprehensive review of the literature.

CASE REPORT: A 38-year-old woman presented with progressively worsening low back pain that radiated to both legs. Neurological examination revealed a weakness of the left leg without sensory loss. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated an epidural tumor at L1-L2 level, making an obtuse angle with the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) on sagittal T2-weighted images. The patient underwent a complete tumor resection without complications or recurrence. The histology revealed a capillary hemangioma.

CONCLUSIONS: SECH is exceedingly rare, with only 22 cases in the reported literature. Females are more commonly affected than males, and the thoracic spine is more commonly involved than the lumbar spine. SECH often mimics other epidural and IDEM lesions, leading to misdiagnosis. MRI is useful to differentiate SECH from lesions in the various spinal compartments; additionally, MRI is essential for preoperative planning and patient surveillance. Preoperative embolization is an option given the high vascularity of SECH. Surgery is the mainstay treatment, with a good prognosis, in most cases without recurrence.

Keywords: Epidural Neoplasms, hemangioblastoma, Hemangioma, Capillary, paraganglioma, Adult, Epidural Space, Female, Humans, Lumbar Vertebrae, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Male

Background

Hemangiomas are congenital vascular malformations, classified according to the predominant vascular morphology: cavernous, capillary, arteriovenous or venous [1]. Capillary hemangiomas are the most common subtype [1]. They occur frequently in the skin and soft tissues of younger individuals and are rarely found in the central nervous system (CNS) [2,3]. Capillary hemangiomas can arise from any compartment of the spine, although they are more commonly found in the intradural extramedullary (IDEM) location [2]. Spinal epidural capillary hemangiomas (SECH) are exceedingly rare. We here present a unique case of a woman with a histologically proven SECH in the upper lumbar spine. The imaging and histopathological characteristics, as well as treatment strategy of this abnormally located vascular lesion in the spine, are highlighted along with a comprehensive review of the literature.

Case Report

A 38-year-old ethnic Malay woman presented to the emergency department with progressive worsening low back pain and radiating pain to both thighs and the lateral aspect of the left calf. In addition, she was concerned about her unsteady gait and episodes of leg cramps followed by ‘pin and needles’ paresthesia in both thighs, including the knees. Her symptoms had worsened over the last 3 months such that she had difficulty riding a motorcycle. She had no significant past medical history. Neurological examination revealed a diffuse mild weakness of the muscles of the left leg (4/5) without any loss of sensation to pain or temperature. The initial lumbar spine radiograph was unremarkable. She was subsequently seen at the outpatient orthopaedic service with persistent symptoms.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine (Figure 1A–1G) was performed using a 1.5 Tesla MR system (MAGNETOM Avanto, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The following MRI protocol was conducted: axial and sagittal T1-and T2-weighted, and post gadolinium axial and sagittal T1-weighted fat-saturated sequences. MRI showed a well-defined and homogeneous enhancing lesion in the posterior aspect of the spinal canal at the L1–L2 level, measuring approximately 1.1×2.0×5.0 cm (anteroposterior x transverse x craniocaudal) in size. The lesion formed an obtuse angle with the adjacent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) on the sagittal T2-weighted image (Figure 1B). There were no significant intratumoral flow voids. Sagittal (Figure 1B) and axial T2w (Figure 1E) images showed anterior displacement and compression of the cauda equina and the posterior dura layer by the tumor. As the epidural lesion was covered by an overlying dura, it has the appearance of a “marble under the carpet” where the marble represents the lesion and the carpet resembles the dura mater [4].

Surgical resection was indicated based on the progression of the patient’s symptoms and the degrees of compression on the cauda equina. The patient underwent L1–L2 laminectomy with complete tumor excision without complications. Preoperative embolization was not deemed necessary given the lack of intratumoral flow voids on the diagnostic MRI study. Histopathological examination revealed a capillary hemangioma (Figure 2A, 2B). Oral analgesics and intravenous opioids were administered for postoperative pain management. There was a gradual improvement of her gait and reduction of paresthesia in her legs. She was discharged on the fourth postoperative day after a short course of physiotherapy and occupational therapy. There was no evidence of clinical or radiological recurrence over 3 years of follow-up after surgery.

Discussion

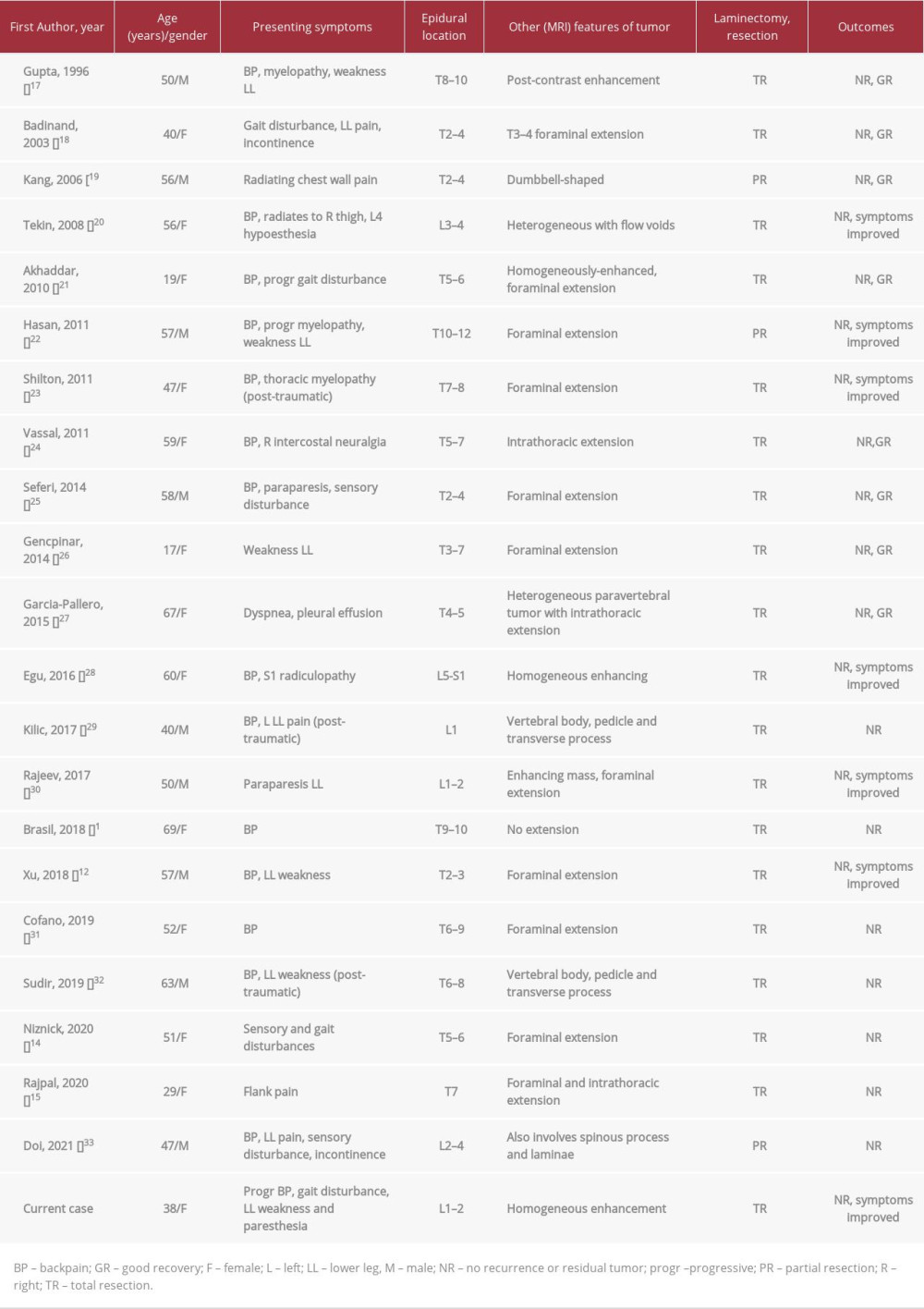

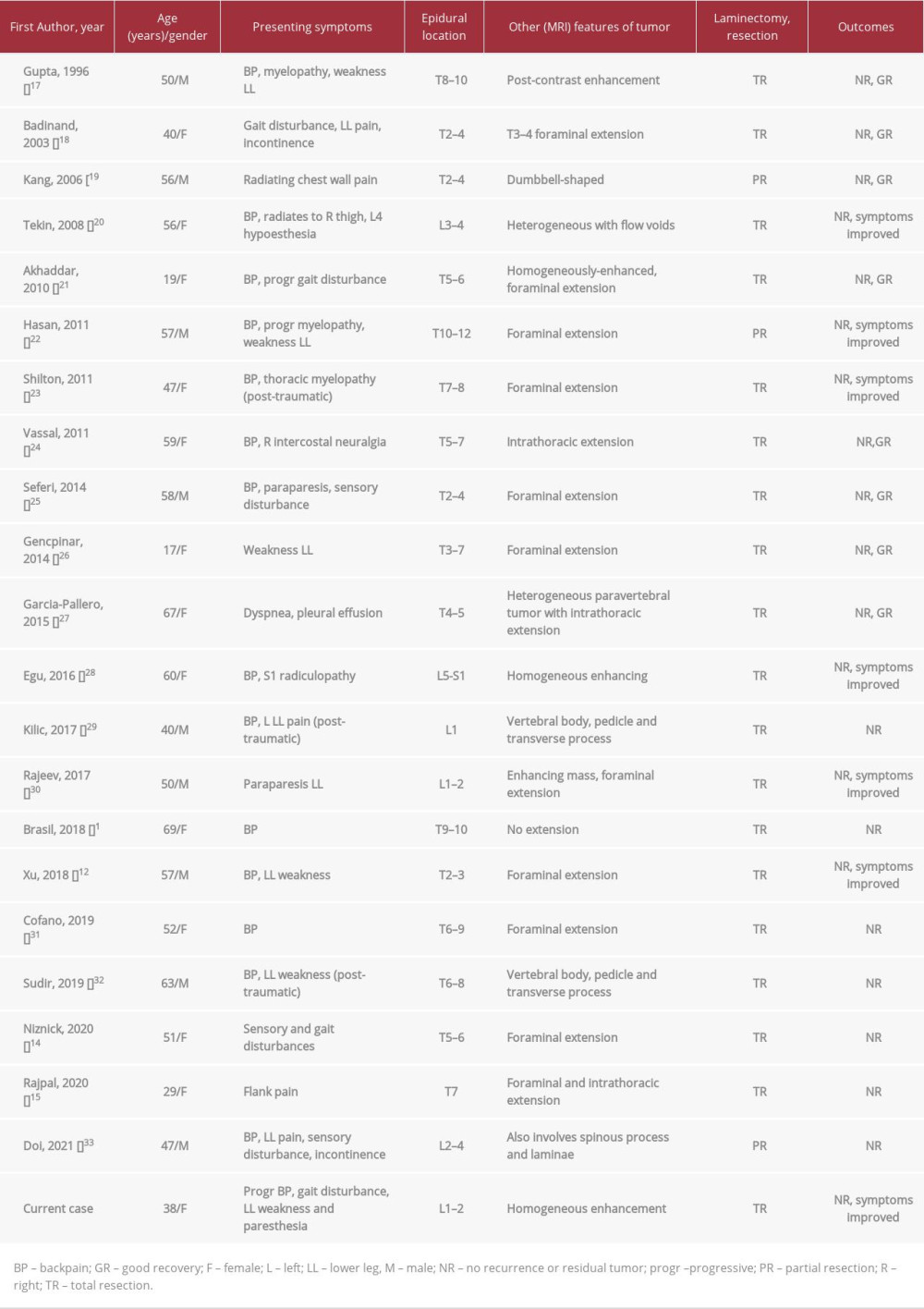

Capillary hemangiomas in the epidural location are exceedingly rare, with only 22 reported cases (including our current case) thus far in the literature (Table 1). Most patients present in their fourth to fifth decades of life, with ages ranging from 17 to 69 years and a median age of 49.2 years (Table 1). There is a slight predilection for females, with the male-to-female ratio of 9: 13. These benign vascular lesions occur more frequently in the thoracic (16/22, 72%) than the lumbar spine (6/22, 27%) (Table 1). Half of the cases showed foraminal extension, which allowed differentiation from cavernous hemangioma [1]. Owing to the slow-growing nature of SECH, most patients present with back pain, progressive myelopathy, or radiculopathy (Table 1) [2,5]. There were a few post-traumatic-related cases of SECH without a definite pathophysiological cause identified.

Capillary hemangiomas can arise from the vasa nervosum or blood vessels of the nerve roots in the cauda equina, the surface of the dura, or the pial surface of the spinal cord, but none were found within the spinal cord [2]. Histologically, capillary hemangiomas are characterized by lobules of thin-walled and irregular capillary-sized vessels lined by endothelial cells, enveloped by fibrous stroma or capsule. They are often associated with feeding vessels [6].

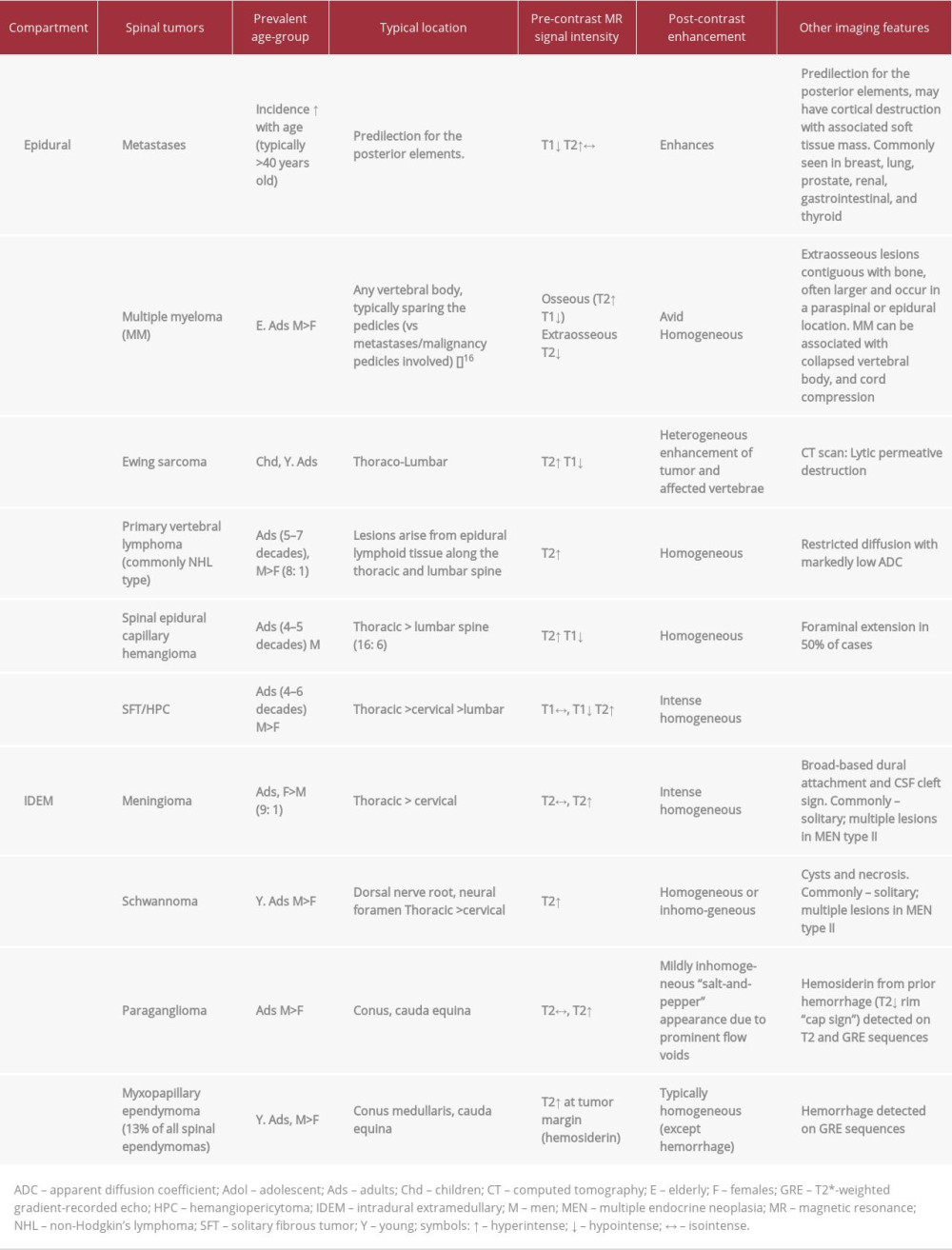

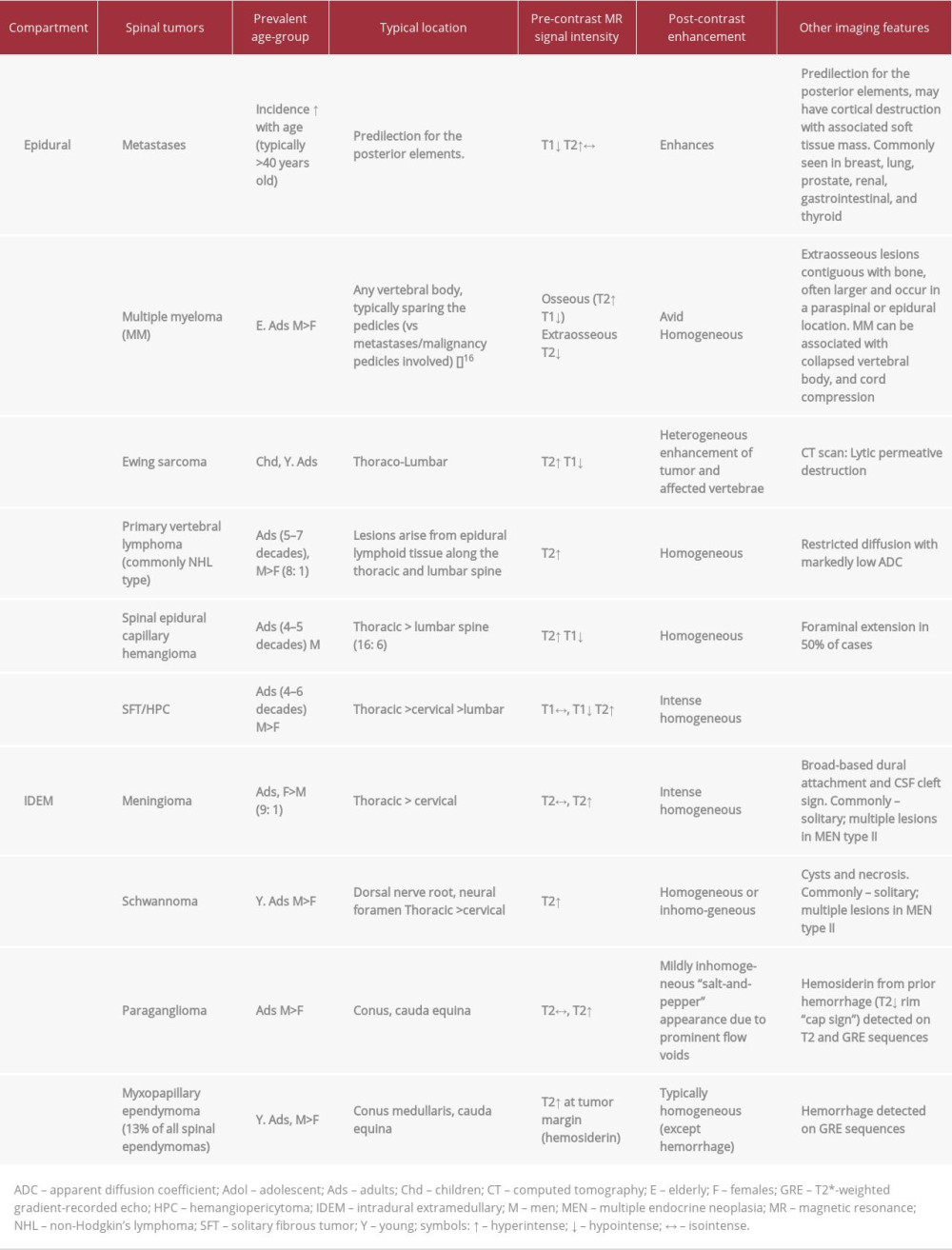

MRI is the primary imaging modality for diagnosis, pre-treatment planning, and surveillance of all spinal lesions, including SECH (Figure 3). The advantages of MRI are the ability to narrow the differential diagnosis by defining the tumor location, signal characteristics, and the relationship of the mass to the cord, dura, and nerve root [7]. In addition, it can help to identify multiple or secondary lesions along the spine, including metastatic deposits, drop metastases, and large feeding or draining vessels [8]. Typical MR imaging features of capillary hemangioma include well-circumscribed tumor margins and typical location in the posterior portion of the spinal canal. SECH can occasionally efface the posterior epidural fat of the spine without involving the posterior elements of the vertebra (Figure 1C). The tumor often demonstrates T1-weighted isointensity relative to the spinal cord and T2-weighted hyper-intensity, as well as avid and homogeneous post-contrast enhancement [2,8,9]. The presence of flow voids and/or avid enhancement of the tumor is reflective of its vascular nature [10]. These features are, however, non-specific, hence it can be challenging to distinguish SECH from other epidural tumors on imaging. Histologic confirmation is necessary in most cases. Examples of other spinal epidural tumors include metastases, multiple myeloma, lymphoma, hemangiopericytoma, meningioma, Ewing’s sarcoma, and myeloid sarcoma (Table 2) [11]. Common metastases to the spine usually originate from a non-CNS primary malignancy (eg, breast, lung, prostate, renal, gastrointestinal and thyroid carcinoma) [12]. The common nonneoplastic lesions found in the epidural compartment include disc herniation, epidural hematoma, lipomatosis, venous plexus, and abscess (Figure 3) [13].

Capillary hemangiomas are also found in the intradural extramedullary (IDEM) compartment with a predilection for the conus and the lumbar spine [2]. It can be challenging to identify the correct compartment from where the lesion arises. Epidural tumors commonly obliterate the CSF space within the spinal canal, unlike IDEM, in which the surrounding CSF space is preserved (Table 2) [2]. Additionally, the dura and the thecal sac would be displaced together, away from the epidural mass. An obtuse angle is typically formed between the epidural mass and the adjacent CSF with a ‘marble under the carpet’ appearance on sagittal T2w images; the marble represents the tumor and the carpet resembles the overlying dura mater [4]. The cord may appear widened in one plane due to pressure from the epidural mass, surrounded by a thin layer of contrast [4].

Conversely, IDEM tumors commonly form an acute angle with the cord/CSF on sagittal T2w images, giving the appearance of “marble on the carpet” (Figures 1, 3).

Capillary hemangiomas are often misdiagnosed radiologically as being meningiomas and schwannomas; all of them demonstrate avid post-contrast enhancement [9]. Meningioma usually shows T1-weighted iso- or slight hypointensity, and iso- or slight T2 hyperintensity [9]. The ‘dural-tail sign’ is not always a reliable feature to differentiate between meningioma and capillary hemangioma, since the latter occasionally arises from the surface of the dura mater, resembling a dura-tail. Other imaging characteristics of meningioma such as the ‘CSF cleft sign’ and bony hyperostosis are perhaps more useful distinguishing features. Schwannomas are typically hypointense on T1-weighted and hyperintense on T2-weighted images with occasional cystic change or necrosis, which can distinguish them from capillary hemangioma [9]. The precise preoperative differentiation between meningioma/schwannoma from capillary hemangiomas is not crucial to management, since these are non-aggressive tumors. Vascular lesions in the spine with flow voids often mimic capillary hemangioma and vice versa; these include paraganglioma, intradural arteriovenous malformation/fistula (AVM/AVF), and hemangioendothelioma [10]. Paragangliomas contain vascular flow voids in the form of ‘salt-and-pepper’ appearance (unlike capillary hemangiomas), while hemangioendothelioma involves the vertebral bodies as osteolytic lesions with soft tissue components in the epidural space [10]. AVM/AVF typically appear as serpiginous structures in the perimedullary regions of the spine (Table 2) [10].

Analysis of the configuration and location of tumors on MRI is highly important for surgical planning and to guide tumor resection (Table 2). In addition, the tumor extension and vascularity can be better assessed on MRI [3,8].

Although considered benign, capillary hemangiomas can cause spinal cord or cauda equina compression, as well as foramina extension ([15] – see Table 1). There is also the risk of rare hemorrhagic complications due to the vascular nature of the lesion. Surgery should be considered even in the absence of neurological symptoms. To reduce intraoperative hemorrhage, preoperative angiography and/or embolization can be considered4[3,6]. In our case, preoperative embolization was not deemed necessary given the lack of intralesional flow voids on the diagnostic MRI study. With adequate preoperative planning, total surgical resection can be achieved in most cases by carefully dissecting the lesion away from the dura while exercising judicious hemostasis by eliminating all arterial feeders. The prognosis is good, in most cases with no recurrence (Table 1).

Conclusions

MRI is essential for diagnosis, preoperative planning, and patient surveillance. Knowledge of the MRI characteristics of spinal lesions and their locations within the spinal compartments can help narrow their differential diagnosis. SECH can be differentiated from IDEM lesions, whereby these lesions form obtuse and acute angles with the CSF, respectively. Some SECH demonstrate foraminal extension distinguishing them from cavernous hemangioma. Nevertheless, surgical resection is the mainstay treatment for capillary hemangioma, with a good prognosis, in most cases without recurrence.

Figures

References:

1.. Brasil AVB, Rohrmoser RG, Gago G, Cambruzzi E, Atypical spinal epidural capillary hemangioma: case report: Surg Neurol Int, 2018; 9; 198

2.. Takata Y, Sakai T, Higashino K, Intradural extramedullary capillary hemangioma in the upper thoracic spine: A review of the literature: Case Rep Orthop, 2014; 2014; 604131

3.. Chung SK, Nam TK, Park SW, Hwang SN, Capillary hemangioma of the thoracic spinal cord: J Korean Neurosurg Soc, 2010; 48(3); 272-75

4.. Brant WE, Helms CA: Differential diagnosis of spinal lesions by location In Fundamentals of Diagnostic Radiology, 2007; 276, Philadelphia (PA), Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

5.. Choi BY, Chang KH, Choe G, Spinal intradural extramedullary capillary hemangioma: MR imaging findings: Am J Neuroradiol, 2001; 22(4); 799-802

6.. Roncaroli F, Scheithauer BW, Krauss WE, Capillary hemangioma of the spinal cord. Report of four cases: J Neurosurg, 2000; 93(1); 148-51

7.. Imagama S, Ito Z, Wakao N, Differentiation of localization of spinal hemangioblastomas based on imaging and pathological findings: Eur Spine J, 2011; 20(8); 1377-84

8.. Sonawane DV, Jagtap SA, Mathesul AA, Intradural extramedullary capillary hemangioma of lower thoracic spinal cord: Indian J Orthop, 2012; 46(4); 475-78

9.. Chung JY, Lee JJ, Kim HJ, Characterization of magnetic resonance images for spinal cord tumors: Asian Spine J, 2008; 2; 15-21

10.. Niznick N, Nguyen TB, Bourque PR, Spinal capillary hemangioma: A rare benign extradural tumor: Can J Neurol Sci, 2020; 47(4); 549-50

11.. Rodallec MH, Feydy A, Larousserie F, Diagnostic imaging of solitary tumors of the spine: what to do and say: Radiographics, 2008; 28(4); 1019-41

12.. Algra PR, Bloem JL, Tissing H, Falke , Detection of vertebral metastases: Comparison between MR imaging and bone scintigraphy: Radiographics, 1991; 11(2); 219-32

13.. Diehn FE, Maus TP, Morris JM, Uncommon manifestations of inter-vertebral disk pathologic conditions: Radiographics, 2016; 36(3); 801-23

14.. Xu H, Tong M, Liu J, Purely spinal epidural capillary hemangiomas: J Craniofac Surg, 2018; 29(3); 769-71

15.. Rajpal S, Johs S, Zaronias C, Spinal epidural capillary hemangioma with intrathoracic extension: case report and review of the literature: Cureus, 2020; 12(7); 9358

16.. Jacobson HG, Poppel MH, Shapiro JH, Grossberger S, The vertebral pedicle sign: A roentgen finding to differentiate metastatic carcinoma from multiple myeloma: Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med, 1958; 80(5); 817-21

17.. Gupta S, Kumar S, Banerji D, Magnetic resonance imaging features of an epidural spinal haemangioma: Australas Radiol, 1996; 40(3); 342-44

18.. Badinand B, Morel C, Kopp N, Dumbbell-shaped epidural capillary hemangioma: Am J Neuroradiol, 2003; 24(2); 190-92

19.. Kang JS, Lillehei KO, Kleinschmidt-Demasters BK, Proximal nerve root capillary hemangioma presenting as a lung mass with bandlike chest pain: Case report and review of literature: Surg Neurol, 2006; 65(6); 584-89

20.. Tekin T, Bayrakli F, Simsek H, Lumbar epidural capillary hemangioma presenting as lumbar disc herniation disease: Case report: Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2008; 33(21); 795-97

21.. Akhaddar A, Oukabli M, En-Nouali H, Acute postpartum paraplegia caused by spinal extradural capillary hemangioma: Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 2010; 108(1); 75-76

22.. Hasan A, Guiot MC, Torres C, A case of a spinal epidural capillary hemangioma: Case report: Neurosurgery, 2011; 68(3); 850-53

23.. Shilton H, Goldschlager T, Kelman A, Delayed post-traumatic capillary haemangioma of the spine: J Clin Neurosci, 2011; 18(11); 1546-47

24.. Vassal F, Péoc’h M, Nuti C, Epidural capillary hemangioma of the thoracic spine with proximal nerve root involvement and extraforaminal extension: Acta Neurochir (Wien), 2011; 153(11); 2279-81

25.. Seferi A, Alimehmeti R, Vyshka G, Case study of a spinal epidural capillary hemangioma: A 4-year postoperative follow-up: Global Spine J, 2014; 4(1); 55-58

26.. Gencpinar P, Açıkbaş SC, Nur BG, Epidural capillary hemangioma: A review of the literature: Clin Neurol Neurosurg, 2014; 126; 99-102

27.. García-Pallero MA, Torres CV, García-Navarrete E, Dumbbell-shaped epidural capillary hemangioma presenting as a lung mass: Case report and review of the literature: Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2015; 40(14); 849-53

28.. Egu K, Kinata-Bambino S, Mounadi M, [Lumbosacral epidural capillary hemangioma mimicking a dumbbell-shaped neurinoma: A case report and review of the literature.]: Neurochirurgie, 2016; 62(2); 113-17 [in French]

29.. Kilic K, Unal E, Toktas ZO, Posttraumatic progressive vertebral hemangioma induced by a fracture: Case Rep Surg, 2017; 2017; 8280678

30.. Rajeev MP, Waykule PY, Pavitharan VM, Spinal epidural capillary hemangioma: A rare case report with a review of literature: Surg Neurol Int, 2017; 8; 123

31.. Cofano F, Marengo N, Pecoraro F, Spinal epidural capillary hemangioma: Case report and review of the literature: Br J Neurosurg, 2019 [Online ahead of print]

32.. Sudhir G, Jayabalan V, Manohar TH, Posttraumatic thoracic epidural capillary hemangioma – a rare case report: Surg Neurol Int, 2020; 11; 179

33.. Doi K, Ohara Y, Hara T, Rapid growth of spinal epidural capillary hemangioma associated with isolated intraosseous lesion at the same level: A case report: J Neurol Stroke, 2021; 11(3); 84-89

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Summary of all the reported cases of spinal epidural capillary hemangioma in the literature.

Table 1.. Summary of all the reported cases of spinal epidural capillary hemangioma in the literature. Table 2.. Differentiating spinal epidural capillary hemangioma from other epidural and intradural extramedullary tumors.

Table 2.. Differentiating spinal epidural capillary hemangioma from other epidural and intradural extramedullary tumors. Table 1.. Summary of all the reported cases of spinal epidural capillary hemangioma in the literature.

Table 1.. Summary of all the reported cases of spinal epidural capillary hemangioma in the literature. Table 2.. Differentiating spinal epidural capillary hemangioma from other epidural and intradural extramedullary tumors.

Table 2.. Differentiating spinal epidural capillary hemangioma from other epidural and intradural extramedullary tumors. In Press

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943118

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942826

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942770

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943214

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250