06 July 2022: Articles

Clozapine-Induced Myocarditis in a Young Man with Refractory Schizophrenia: Case Report of a Rare Adverse Event and Review of the Literature

Unusual clinical course, Unusual or unexpected effect of treatment, Adverse events of drug therapy, Educational Purpose (only if useful for a systematic review or synthesis)

Adebola Oluwabusayo Adetiloye1ADEF*, Wael Abdelmottaleb1ABDEF, Mirza Fawad Ahmed1BDEF, Ana Maria Victoria1BE, Mustafa Bilal OzbayDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.936306

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936306

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Myocarditis is cardiac muscle inflammation caused by infectious or noninfectious agents. Rarely, clozapine, an atypical antipsychotic drug used to treat resistant schizophrenia, has been reported to cause myocarditis, as we report in this case.

CASE REPORT: A 29-year-old man, who was known to have schizophrenia and was on olanzapine therapy, presented in our Emergency Department with active psychosis, and was subsequently admitted to the psychiatric ward for refractory schizophrenia. He was started on clozapine, which was cross-titrated with olanzapine. On day 20 of being treated with clozapine, he developed a high-grade fever and chest pain. EKG demonstrated new-onset prolonged QT corrected for heart rate (QTc), premature ventricular contractions, ST-T wave changes with an increased ventricular rate, and ventricular bigeminy with elevated troponin and inflammatory markers. Echocardiography showed a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Coronary angiography showed normal coronary arteries, low cardiac output, and cardiac index consistent with cardiogenic shock was also observed. Other pertinent laboratory results included negative respiratory viral panel, including COVID-19 PCR, negative blood cultures, and negative stool screen for ova and parasite. Clozapine was discontinued and the patient received management for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. He improved clinically with return of EKG to normal sinus rhythm and improved left ventricular ejection fraction on repeat echocardiogram.

CONCLUSIONS: Acute myocarditis can occur due to a myriad of causes, both infectious and noninfectious; thus, determining the lesser-known causes, such as drug-related etiology, is essential to provide appropriate treatment for patients.

Keywords: Antipsychotic Agents, myocarditis, clozapine, Drug Hypersensitivity, Heart Failure, Adult, COVID-19, Humans, Male, olanzapine, Schizophrenia, Schizophrenia, Treatment-Resistant, Stroke Volume, Ventricular Function, Left

Background

Myocarditis is an inflammatory disease of the cardiac muscle that can be caused by infectious and noninfectious conditions with focal or diffuse involvement of the myocardium. Myocarditis is often caused by cardiotropic viruses, and the presentation is often mild and self-limited [1]. However, in severe cases patients can develop acute cardiomyopathy with severe arrhythmias, cardiogenic shock, and sudden cardiac death [1,2]. The actual incidence of myocarditis is unknown as presentation is variable and the criterion standard for diagnosis is biopsy [3].

Clozapine was the first atypical antipsychotic approved for treatment of schizophrenia. Due to its association with severe and potentially fatal adverse effects, especially agranulocytosis and acute liver injury, its use is restricted to treatment-resistant schizophrenia, and monitoring during treatment is required [4]. Myocarditis as a complication of clozapine therapy is even more challenging as it is a rare adverse effect of this antipsychotic medication [5]. According to the literature, clozapine is the most commonly used antipsychotic to induce myocarditis typically occurring early in treatment, but knowledge is still scarce on the incidence and the pathogenesis of clozapine-induced myocarditis [5]. Therefore, it is important to closely monitor patients on antipsychotic medications, especially clozapine, for the development of this rare and potentially life-threatening complication.

Case Report

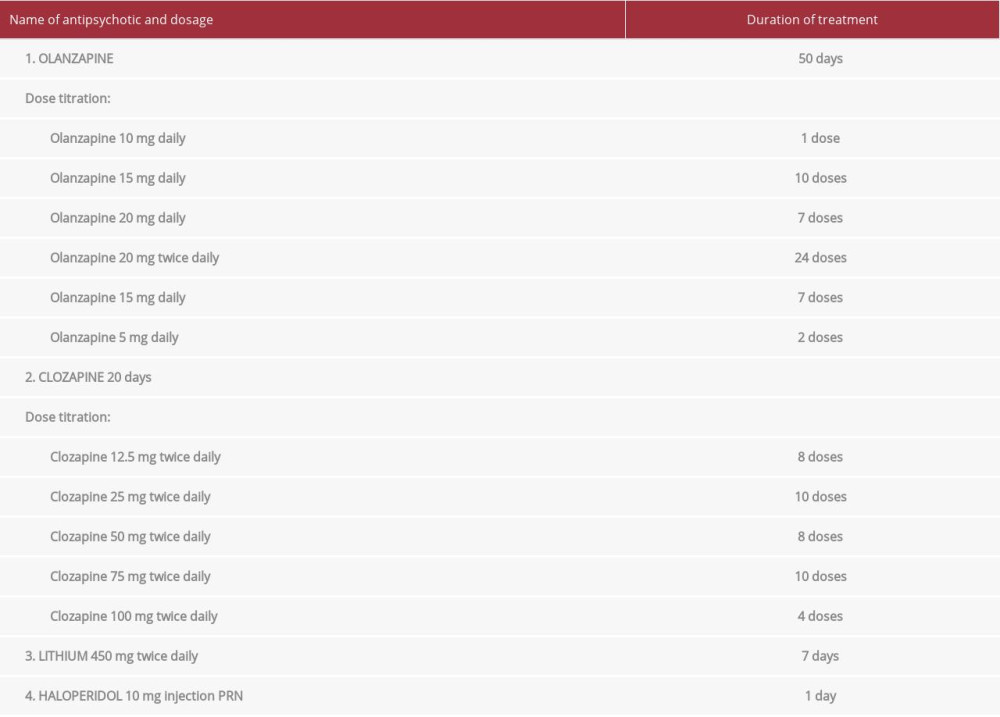

A 29-year-old man with a medical history of schizophrenia, non-response to risperidone, and multiple admission to the Psychiatry Ward presented to the Emergency Department with active psychosis and was admitted to the Psychiatry Ward. He was on olanzapine for almost 3 months prior to this admission. During his management, clozapine was initiated at a dose of 12.5 mg twice daily, which was titrated up to 100 mg twice daily over a period of 18 days, cross-titrated with olanzapine. He was also commenced on lithium 450 mg twice a day and haloperidol injection as needed (see Table 1). Twenty days after starting clozapine, the patient developed a fever of 38.4°C without an apparent source, necessitating transfer to the medical floor for further evaluation.

While on the medical floor, he was worked up for possible sources of infection, including chest X-ray and cultures. An electrocardiogram (EKG) obtained to monitor the QTc while on antipsychotics showed prolonged QTc of 562 and frequent polymorphic ventricular complexes. These changes were not noted on the patient’s previous EKG, which showed normal sinus (Figure 1). A chest X-ray was unremarkable. The patient’s complete metabolic profile at this time showed mild hyponatremia (132 mEq/L), but other electrolytes, including potassium, magnesium, chloride, and calcium, were within normal limits. Renal function was within normal range. Complete blood count (CBC) was negative for leukocytosis and leukopenia. However, eosinophilia was noted on CBC trend, with peak value of 1.23×10(3)/mcL (0–500/mcL). The baseline eosinophil count was 0.34×10(3)/mcL prior to initiation of clozapine therapy. Troponin T was elevated to 3.070 ng/ml (0.000–0.010 ng/ml) and Pro BNP was elevated to 6056.0 pg/ml (1–125 pg/ml). He was subsequently upgraded to the Cardiac Care Unit (CCU) for further management.

During the patient’s stay at the CCU, he reported mild chest pain and dyspnea, which were new to him, but he denied palpitations and other cardiovascular symptoms. He also denied myalgias, headache, sore throat, and recent symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection. Troponin T trend was followed, and it remained persistently elevated over 48 hours, with a peak value of 4.09 ng/ml (0.000–0.010 ng/ml). Inflammatory markers were elevated, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 50 mm/hr (0–15 mm/h) and C-reactive protein 125.9 mg/L (0.0–5.0 mg/L). Creatine phosphokinase was 674 U/L (20–200 U/L), liver function tests were unremarkable, and a respiratory viral panel including COVID-19 PCR was negative. EKG showed sinus rhythm, with new RBBB and ventricular bigeminy (Figure 2). All antipsychotics were held due to the likelihood of antipsychotic-induced cardiotoxicity. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) showed a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 25% with a normal LV size and wall thickness with a normal RV size. Both right and left atria were normal in size (Video 1).

The patient underwent cardiac catheterization for new-onset heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), which was unexplained. The procedure revealed angiographically normal left (Figure 3) and right (Figure 4) coronaries, elevated right and left heart filling pressures, mild pulmonary hyper-tension with mean pulmonary arterial pressure 32 mmHg (12–16 mmHg), low cardiac output of 3.0 L/min (4.0–8.0L/min) and low cardiac index 1.1 L/min/m2 (2.5–4.0 L/min/m2), consistent with cardiogenic shock. The pulmonary artery pulsatility index of 2 was consistent with preserved right ventricular function. Based on new-onset heart failure, EKG changes, elevated cardiac biomarkers, and eosinophilia within days of initiation of clozapine therapy, and absence of another probable cause, the diagnosis of acute myocarditis likely clozapine-induced was made.

Milrinone, losartan, and metoprolol were started, with improvement of cardiac index to 2.29 L/min/m2. During the course of admission, his dyspnea improved, fever subsided, and the eosinophil count trended down. Cultures (blood and urine) and ova and parasite stool screen came back negative. The patient was discharged back to Psychiatry after 14 days of admission in the CCU. Prior to discharge, a repeat TTE showed improvement of LVEF from 25% to 55% (Video 2), while EKG showed NSR without arrythmias (Figure 5).

Discussion

Clozapine is a second-generation antipsychotic used for the management of schizophrenia, a complex chronic brain disorder that affects less than 1% of the U.S. population [6]. Currently, there is no cure for schizophrenia and antipsychotic drugs are the mainstay of treatment. First-generation anti-psychotics potently block dopamine D2 receptor, which correlates with clinical potency as well as extrapyramidal adverse effects [4]. Clozapine, first developed in 1959, was classified as an atypical antipsychotic because, unlike the first-generation antipsychotics, it displayed clinical efficacy without a potent dopamine D2 receptor blockade, thereby reducing the risk for extrapyramidal adverse effects [4]. Clozapine acts as an antagonist on dopamine, serotonin, alpha-adrenergic, histamine H1, and cholinergic receptors, with the highest affinity for the D4 dopamine receptor and weak D2 blocking properties [7]. It is known to cause agranulocytosis, sedation, seizures, and weight gain but also it can cause more serious but rare adverse effects like myocarditis [8].

Current guidelines recommend clozapine for treatment of resistant schizophrenia or those with substantial risk of suicide or suicide attempts, and therapy requires monitoring for agranulocytosis at baseline and periodically, usually weekly to monthly [9]. However, less emphasis was placed on monitoring for myocarditis. Postulated risk factors for clozapine-induced myocarditis include genetic polymorphisms affecting drug metabolism, co-administration with other psychotropic medication, and rapid dose titration [10,11]. Some guidelines recommend baseline EKG and avoidance of clozapine therapy in patients with congenital long QT syndrome, individuals with persistent corrected QT interval (QTc) >500 ms on EKG, and cardiology consultation for higher-risk clinical patients such as those with known heart disease [10]. Despite the potentially lethal clozapine-induced cardiac toxicity, there are no recommendations for periodic EKG or cardiac enzyme monitoring for changes that could herald the development of myocarditis, especially in patients without known cardiovascular diseases [10]. In recent reviews, the incidence of myocarditis associated with clozapine exposure was 3%, which may lead to cardiomyopathy as described in our present case, usually occurring during the first 2–3 months of treatment initiation [13]. Our patient developed early cardiotoxicity (≤2 months) during the first month of treatment with clozapine, which according to a systematic review occurs in <0.1 to 1.0% of patients, making this adverse effect rare [14]. Although quetiapine, olanzapine, aripiprazole, amisulpride, and lithium have all been reported to cause myocarditis, the risk of developing myocarditis with non-clozapine antipsychotics is very low; however, the risk of myocarditis is increased when co-administered with clozapine [11,15].

The mechanism of clozapine myocarditis is still not clearly understood, but possible causes have been proposed, like IgE-mediated hypersensitivity, cholinergic dysfunction, and genetic predisposition [16]. Our patient had eosinophilia, which was a finding noted in 66% of patients with clozapine-induced myocarditis according to a report, suggesting a strong likelihood of IgE-mediated hypersensitivity as a causal or contributing factor [17]. Clozapine has also been linked to development of cardiomyopathy with reduction in LVEF in the absence of coronary artery disease, hypertension, valvular disease, and congenital heart disease sufficient to explain the observed myocardial abnormality. Reports have mentioned that the time to onset of clozapine-induced cardiomyopathy can vary between 3 weeks to 4 years, with most cases occurring 6–9 months after initiation of clozapine [18]. Clozapine-induced cardiomyopathy does not appear to be dose-dependent, ensuing with doses ranging from 125 mg to 700 mg and mean dose of 360 mg [18]. In the U.S. FDA report, the median dose was 450 mg in patients who survived and 400 mg daily in patients who died from clozapine-induced cardiomyopathy [18]. Whether cardiomyopathy related to clozapine use is a consequence of myocarditis being unrecognized in the early stages, or a clinically distinct and chronic cardiac disorder, is still being investigated [19].

The clinical presentation of myocarditis is highly variable and non-specific, ranging from no symptoms at all, to dyspnea, chest discomfort, arrythmia, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death at the other end of the spectrum. According to Kilian et al, fever, chest pain, and dyspnea were reported as presenting symptoms in 23 cases of myocarditis and cardiomyopathy [20]. In other reports, the most common clinical features were fever and chest pain [13,16]. Our patient presented with fever and vague chest pain but denied having palpitations or fatigue. Apart from an irregular heart rate, our patient had no overt features of heart failure on examination. Diagnosing myocarditis is challenging because its clinical features are non-specific, necessitating a high index of suspicion. A definitive diagnosis of myocarditis is established by diagnostic findings on endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) [21]. According to the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation/European Society of Cardiology (AHA/ACCF/ESC), EMB is recommended for specific situations in which it will offer specific diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic benefits [22]. In patients not meeting the criteria for EMB, myocarditis should be suspected in patients with or without cardiac signs and symptoms who present with a rise in cardiac biomarker levels especially troponin, EKG suggestive of acute myocardial injury, arrhythmia, or abnormalities of ventricular systolic function on echocardiogram or cardiac MRI, especially if these clinical findings are new and unexplained [3]. Other features that support the diagnosis of drug-induced myocarditis include fever, elevated acute-phase reactants, and eosinophilia suggesting IgE-mediated hypersensitivity as seen in the index case, but there is no established clinical marker [22,23]. Although generally not required, our patent had coronary angiography with unremarkable findings.

There are no universal diagnostic criteria for clozapine-induced myocarditis and cardiomyopathy. According to a systematic analysis of drug-related myocarditis, antipsychotic was the first (1979) and most reported class [24]. Ronaldson et al proposed diagnostic criteria for clozapine-associated myocarditis which includes onset of new symptoms within 45 days of initiating clozapine plus histological evidence of myocarditis or signs of cardiac dysfunction plus 1 of the following 5 findings on investigation: elevated troponin level or muscle/brain creatine kinase level >2 times the upper limit of normal, EKG changes consistent with myocarditis, chest radiograph suggestive of heart failure, evidence of ventricular dysfunction, or MRI tissue characterization suggestive of myocarditis [17]. The temporal relationship of these findings in our patient to an implicated medication and absence of other probable etiology (negative respiratory viral panel, negative blood cultures for disseminated bacterial or fungal infection, no known systemic disorders, absence of protozoan and helminthic infection, and absence of exposure to cardiotoxins or other medications known to cause myocarditis) established the diagnosis of clozapine-induced cardiomyopathy in our patient.

Management of drug-induced myocarditis and cardiomyopathy includes discontinuing the offending drug, in this case clozapine, and a possible role for glucocorticoid therapy [25]. Patients with cardiomyopathy, reduced LVEF, and cardiogenic shock are treated with optimal medical care, according to guidelines for the management of heart failure. Sustained ventricular arrhythmias should be treated with urgent cardioversion while recurrent arrhythmias and non-sustained ventricular arrythmia should be treated with antiarrhythmic drugs. Cardiac device implantation for the management of ventricular arrythmia should be evaluated after the resolution of reversible acute myocarditis, generally within 3 to 6 months [22]. Discontinuation of clozapine often leads to partial or full clinical recovery, but the mortality rate of clozapine-induced myocarditis and cardiomyopathy varies according to different reports, with fatalities averaging 25% [14,15]. According to a systematic review of 144 articles, recommendation for monitoring patents on clozapine therapy vary widely. For daily practice, some authors recommended baseline laboratory investigations, with or without follow-up for C-reactive protein, troponin, and electrocardiography; echocardiography was less commonly recommended but was a consideration [26]. Given the potentially fatal outcome of clozapine-induced cardiomyopathy, we recommend a more detailed guideline for initiation and follow-up of patients on clozapine therapy, identification of potential risk factors for clozapine-induced cardiotoxicity, and a possible genetic screening of some patients based on post-marketing surveillance. In addition, if myocarditis or cardiomyopathy is suspected, clozapine should be stopped and prompt evaluation by a cardiologist sought to ensure appropriate management and prevention of fatal outcomes.

Conclusions

To summarize, acute myocarditis has several etiologies, with viral infection being the most common. However, antipsychotic-related myocarditis, in particular clozapine, is a rare causative factor with potentially devastating consequences such as life-threatening cardiac arrythmias, cardiomyopathy, and sudden cardiac death. It is therefore crucial to ensure that providers are aware of this rare but possible adverse effect. In addition, more robust guidelines are needed to ensure adequate pre-therapy baseline evaluation aimed at identifying patients at risk, and subsequent follow-up for early detection and prompt management of clozapine-induced myocarditis.

Figures

References:

1.. Tschöpe C, Cooper LT, Torre-Amione G, Management of myocarditis-related cardiomyopathy in adults: Circ Res, 2019; 124; 1568-83

2.. Kociol RD, Cooper LT, Fang JC, Recognition and initial management of fulminant myocarditis: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association: Circulation, 2020; 141(6); e69-92

3.. Caforio ALP, Pankuweit S, Arbustini E, Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: A position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases: Eur Heart J, 2013; 34; 2636-48

4.. Khokhar JY, Henricks AM, Kirk E, Unique effects of clozapine: A pharmacological perspective: Adv Pharmacol, 2018; 82; 137

5.. Munshi TA, Volochniouk D, Hassan T, Clozapine-induced myocarditis: Is mandatory monitoring warranted for its early recognition?: Case Rep Psychiatry, 2014; 2014; 513108

6.. Schultz SH, North SW, Shields CG, Schizophrenia: A review: Am Fam Physician, 2007; 75; 1821-29

7.. Friedman JH, Seeman P, Atypical antipsychotics mechanisms of action: Can J Psychiatry, 2003; 48; 62-64

8.. De Fazio P, Gaetano R, Caroleo M, Rare and very rare adverse effects of clozapine: Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 2015; 11; 1995-2003

9.. Keepers GA, Fochtmann LJ, Anzia JM, The American psychiatric association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia: Am J Psychiatry, 2020; 177; 868-72

10.. Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, Taylor AJ, Rapid clozapine dose titration and concomitant sodium valproate increase the risk of myocarditis with clozapine: A case-control study: Schizophr Res, 2012; 141; 173-78

11.. Sweeney M, Whiskey E, Patel RK, Understanding and managing cardiac side-effects of second-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: BJPsych Advances, 2020; 26(1); 26-40

12.. Freudenreich O, McEvoy J, Guidelines for prescribing clozapine in schizophrenia UpToDate.

13.. Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, McNeil JJ, Clozapine-induced myocarditis, a widely overlooked adverse reaction: Acta Psychiatr Scand, 2015; 132; 231-40

14.. Curto M, Girardi N, Lionetto L, Systematic review of clozapine cardiotoxicity: Curr Psychiatry Rep, 2016; 18(7); 68

15.. Brady HR, Horgan JH, Lithium and the heart: Unanswered questions: Chest, 1988; 93; 166-69

16.. Datta T, Solomon AJ, Clozapine-induced myocarditis: Oxf Med Case Reports, 2018; 2018; omx080

17.. Ronaldson KJ, Taylor AJ, Fitzgerald PB, Diagnostic characteristics of clozapine-induced myocarditis identified by an analysis of 38 cases and 47 controls: J Clin Psychiatry, 2010; 71(8); 976-81

18.. Alawami M, Wasywich C, Cicovic A, A systematic review of clozapine induced cardiomyopathy: Int J Cardiol, 2014; 176; 315-20

19.. , Clozapine and Achy Breaky Hearts (Myocarditis and Cardiomyopathy) MEDSAFE. Accessed 2022 March 16. Available from: https://www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/puarticles/clozapine.htm

20.. Kilian JG, Kerr K, Lawrence C, Myocarditis and cardiomyopathy associated with clozapine: Lancet, 1999; 354; 1841-45

21.. Im JP, Pellegrini JR, Munshi R, “My heart said it’s swollen”: A rare case of clozapine-induced myocarditis in a schizophrenic patient: Cureus, 2021; 13; e15168

22.. Tschöpe C, Ammirati E, Bozkurt B, Myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy: Current evidence and future directions: Nat Rev Cardiol, 2021; 18(3); 169-93

23.. Taliercio CP, Olney BA, Lie JT, Myocarditis related to drug hypersensitivity: Mayo Clinic proceedings, 1985; 60; 463-68

24.. Nguyen LS, Cooper LT, Kerneis M, Systematic analysis of drug-associated myocarditis reported in the World Health Organization pharmaco-vigilance database: Nat Commun, 2022; 13; 25

25.. Brambatti M, Matassini MV, Adler ED, Eosinophilic myocarditis: characteristics, treatment, and outcomes: J Am Coll Cardiol, 2017; 70; 2363-75

26.. Knoph KN, Morgan RJ, Palmer BA, Clozapine-induced cardiomyopathy and myocarditis monitoring: A systematic review: Schizophr Res, 2018; 199; 17-30

Figures

In Press

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942578

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943801

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942966

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942032

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250