14 August 2022: Articles

Unusual Case of Mirizzi Syndrome Presenting as Painless Jaundice

Unusual clinical course, Challenging differential diagnosis

Justin Bauzon1ABCDEFG*, Sarah Haller1ABEF, Jose R. Aponte-Pieras2ABCDEF, Daisy Lankarani2BCDEF, Ariyon SchreiberDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.936836

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936836

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Isolated painless jaundice is an uncommon presenting sign for Mirizzi syndrome, which is typically characterized by symptoms of acute or chronic cholecystitis. We report a rare case of Mirizzi syndrome with an acute onset of painless obstructive jaundice.

CASE REPORT: A 60-year-old man with an unremarkable prior medical history presented with 1 week of jaundice, dark urine, and acholic stools. His laboratory studies revealed a pattern of cholestasis with marked direct hyperbilirubinemia. Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging studies demonstrated intrahepatic ductal dilation and cholelithiasis, including a stone within the cystic duct. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with SpyGlass cholangioscopy confirmed the diagnosis of Mirizzi syndrome.

CONCLUSIONS: An atypical presentation of Mirizzi syndrome should be suspected in the setting of biliary obstruction without pain. The differential diagnosis is broad and includes choledocholithiasis, ascending cholangitis, and hepatobiliary malignancy. Evaluation should include laboratory studies and biliary tract imaging. Noninvasive biliary tract imaging can help exclude malignancy and confirm ductal dilation but is not sensitive for Mirizzi syndrome. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography can serve both diagnostic as well as therapeutic purposes via stone extraction and stent placement. SpyGlass cholangioscopy can also augment management in the form of Electrohydraulic lithotripsy. Although therapeutic biliary endoscopy can be very effective, cholecystectomy remains the definitive treatment for Mirizzi syndrome.

Keywords: Cholangiopancreatography, Endoscopic Retrograde, Cholestasis, Endosonography, Jaundice, Obstructive, Mirizzi syndrome, Cholecystectomy, choledocholithiasis, Cystic Duct, Humans, Male, Middle Aged

Background

Mirizzi syndrome (MS) is a rare complication of gallstones, affecting approximately 0.1% of the 20 million people afflicted with cholelithiasis in the United States [1]. It is defined by obstruction of the hepatic duct due to external compression from a gallstone impacted within the cystic duct or gallbladder infundibulum [1]. Patients typically present with characteristic clinical findings of biliary colic or cholecystitis, such as abdominal pain, as well as signs of obstructive jaundice [2]. We present a case of MS with an atypical presentation, in which a patient without a prior history of symptomatic gallstones presented with acute onset of painless jaundice.

Case Report

A 60-year-old man with no significant prior medical history presented to the Emergency Department with 1 week of painless jaundice and dark brown urine. The patient reported associated acholic stools and generalized pruritus for 3 days. He denied any abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fevers, or weight loss. His medical history included a negative colonos-copy 2 years prior. He endorsed smoking marijuana daily, having a 10 pack-year history of tobacco use, and drinking 12 cans of beer a week.

The physical examination revealed scleral icterus and full-body jaundice. The patient’s abdomen was nondistended without shifting dullness, was nontender, and had no appreciable organomegaly. No skin lesions, including palmar erythema or spider angiomas, were visualized. Laboratory values showed transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase of 85 IU/L [reference range, 8–34 IU/L], alanine aminotransferase of 184 U/L [reference range, 10–49 U/L]), direct hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin of 22 mg/dL [reference range, 0–1.2 mg4L], conjugated bilirubin of 16.5 mg/dL [reference range, ≤0.5 mg/dL]), and elevated alkaline phosphatase of 433 U/L (reference range, 46–116 U/L) (Table 1). Viral hepatitis panels returned negative. Tumor markers were obtained and were notable for mild elevation of carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 at 49 U/mL (reference range, 0–37 U/mL); alpha feto-protein and carcinoembryonic antigen were within normal limits. Urinalysis showed 3+ bili-rubin, confirming the suspected bilirubinuria. Abdominal ultra-sound showed cholelithiasis with intra- and extrahepatic biliary duct dilation. The patient was admitted for further evaluation.

Serum total bilirubin increased overnight to 26.1 mg/dL. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan, with and without intravenous contrast, was obtained, showing intra- and extra-hepatic biliary dilatation and gallbladder wall thickening. This was followed by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, which demonstrated moderate intrahepatic ductal dilation and cholelithiasis without dilation of the common bile duct (Figure 1). Owing to concern for malignancy, the decision was made to proceed with endoscopic ultrasound, which confirmed intrahepatic ductal dilation without common bile duct dilation; there were no pancreatic, liver, or ductal lesions and thus no biopsies were taken. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) revealed a stone impacted within the cystic duct and dilation of the intrahepatic ducts upstream from the area of impaction, which confirmed a diagnosis of MS (Figure 2). A 10-French by 9-cm plastic biliary stent was placed, with resultant good bile flow (Figure 3).

The patient’s serum bilirubin trended down over the course of 2 days following stent placement but remained within an abnormal range. This raised concern for a proximal intraductal mass, such as cholangiocarcinoma, and a need for further characterization of the cystic duct calculus, which prompted a second ERCP in conjunction with SpyGlass cholangios-copy (Boston Scientific). Following removal of the stent using forceps, the cholangioscope was advanced to the intrahepatic bifurcation, which revealed no abnormality (Figure 4).

The catheter was slowly withdrawn while the duct was irrigated with normal saline. Following cannulation of the cystic duct, the cholangioscope was advanced toward the gallbladder neck. A large cholelith was directly visualized at the junction of the gallbladder neck and cystic duct, with no evidence of fistula; no features suggestive of malignancy were identified in the biliary tree.

General Surgery was consulted for surgical evaluation. However, the patient expressed his wishes for early discharge and outpatient follow-up. Given his down-trending serum bilirubin levels and clinical stability, he agreed to be evaluated for cholecystectomy in the outpatient setting. The patient presented for his outpatient appointment with General Surgery but left before discussing the plan of care with the surgeon, opting against any surgical treatment at that time. Unfortunately, the patient did not return for follow-up and could not be evaluated further.

Discussion

MS is a rare complication of symptomatic cholelithiasis. It has an annual incidence of less than 1%, which increases to 2.7% in patients with a history of cholelithiasis, and up to 25% among patients undergoing gallbladder resection [1,3–6]. There may be a slight propensity for females and older populations [5,7,8], but recent studies have shown no male or female predilection [2]. Over 25% of all patients diagnosed with MS are at risk for gallbladder cancer [9,10].

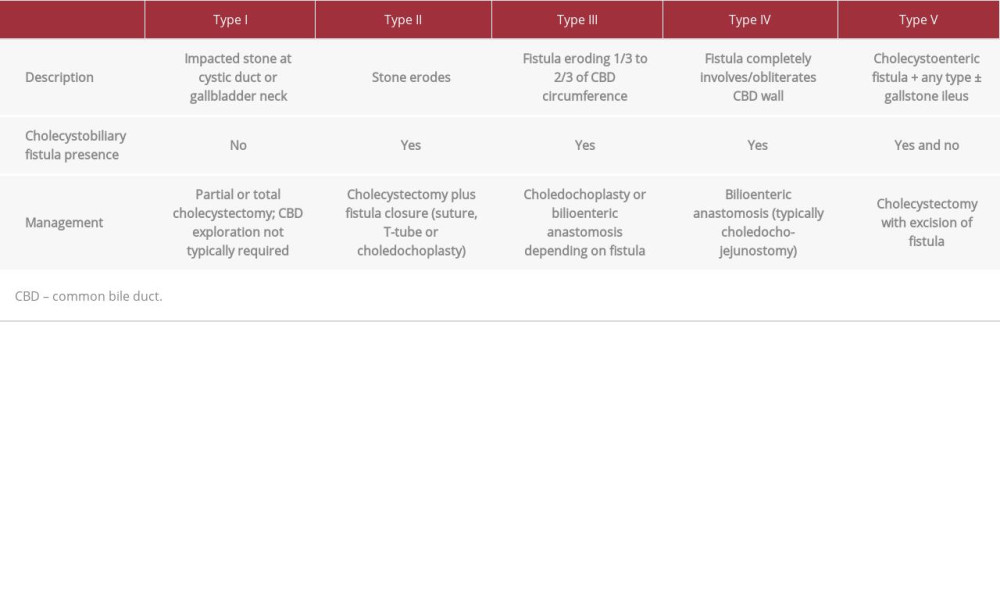

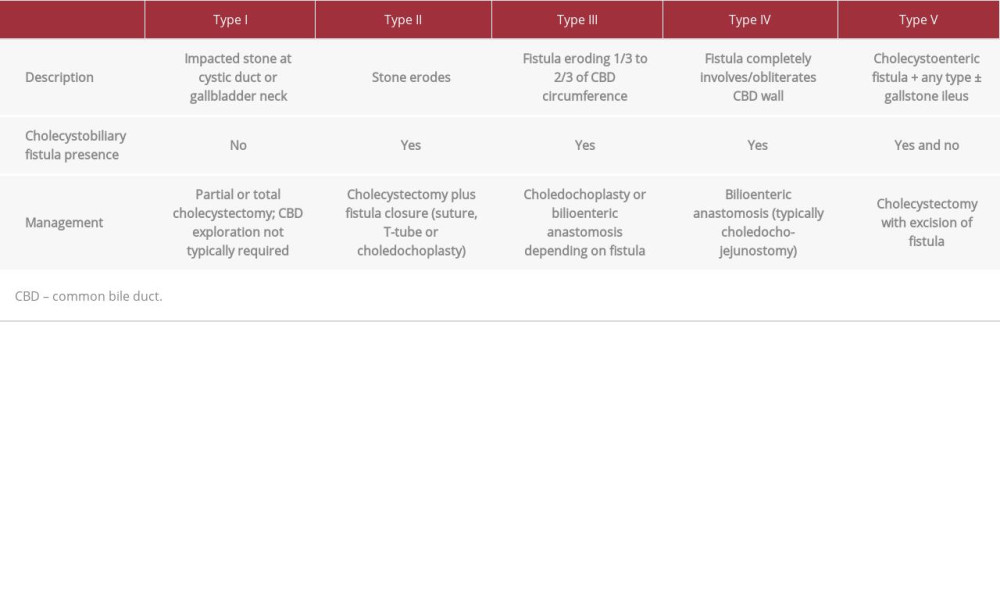

The pathogenesis of MS results from an impacted gallbladder calculus at the cystic duct or infundibulum [9,11]. Gallstone impaction leads to compression of adjacent biliary structures and extrinsic post-hepatic obstruction. A chronic, local inflammatory response can precipitate erosion into the ductal wall and lead to the formation of a fistula [9]. MS is classified into type I, defined as external compression of the bile duct by an impacted stone, and type II through V, which all have some degree of erosion into the common bile duct wall as well as fistulous formation between the gallbladder and adjacent structures (Table 2) [12,13].

MS typically presents with abdominal pain and jaundice, with pain being the most reported feature [2,6,14]. Other associated signs or symptoms include fever, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and weight loss [2,6]. Patients can demonstrate signs of obstructive jaundice such as dark-colored urine and acholic stools [15,16]. A small subset of patients presents asymptomatically [6].

Our case represents a rare presentation of MS with acute painless jaundice. Reports of MS presenting as painless jaundice have been seldom described in the literature and often include other associated symptoms such as weight loss and fatigue, which were absent in this case [17–20]. Our patient’s presentation with signs of painless biliary obstruction is unusual, as patients with MS characteristically present with acute abdominal pain or a history of previous episodes of biliary colic [1].

The differential diagnosis for painless jaundice should raise clinical suspicion for malignancy, namely cholangiocarcinoma, an adenocarcinoma of the pancreas or gallbladder. In our case, the absence of abdominal pain or fever decreased our suspicion for benign biliary diseases, such as choledocholithiasis and ascending cholangitis. Inherited causes of hyperbilirubinemia should be considered after excluding life-threatening etiologies.

An initial evaluation of nonspecific symptoms of jaundice includes laboratory studies to discern between hepatocellular and cholestatic processes: liver enzyme panels and serum conjugated bilirubin levels [2]. Further workup of liver function should include serum levels of albumin, bilirubin, and prothrombin/ international normalized ratio. CA 19-9 levels can be considered if there is concern for malignancy, although elevations have been reported in a few cases of MS, as in ours [17,19,21].

Ultrasonography is routinely performed for workup of acute cholecystitis, and CT scanning can aid in the diagnosis of malignancy; however, both lack sensitivity for MS (48% and 42–50%, respectively) [2,6]. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography is more sensitive and can facilitate the identification of post-hepatic obstruction [2]. ERCP is highly accurate in diagnosing MS and offers potential therapeutic roles in the form of electrohydraulic lithotripsy, stone extraction, and stent placement [1,9,22]. Over half of patients are diagnosed with MS intraoperatively, regardless of preoperative workup [9,10].

Direct cholangioscopy offers an alternative diagnostic modality in assessing for MS. In our patient, the SpyGlass direct visualization system, a single-use cholangioscope, allowed for direct visualization of the impacted gallstone at the gallbladder neck; this finding has been previously reported in the literature [23]. Use of cholangioscopy also offers a potential therapeutic advantage when used in conjunction with electrohydraulic lithotripsy to pulverize the impacted cholelith to relieve the obstruction [24–26].

Conclusions

A high index of suspicion for an atypical presentation of MS should be employed in the setting of painless biliary obstruction. Early identification can help prevent long-standing complications of MS, including the formation of fistulas. Noninvasive biliary tract imaging can help rule out an underlying malignant process but lacks the sensitivity to reliably identify MS. ERCP can serve both a diagnostic and therapeutic role in management. Cholangioscopy can serve to augment the diagnosis of MS as well as offer a potential therapeutic modality through electrohydraulic lithotripsy.

Figures

References:

1.. Jones MW, Ferguson T, Mirizzi syndrome. 2021 Feb 8: StatPearls [Internet] Jan, 2021, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing

2.. Valderrama-Treviño AI, Granados-Romero JJ, Espejel-Deloiza M, Updates in Mirizzi syndrome: Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr, 2017; 6(3); 170-78

3.. Baer HU, Matthews JB, Schweizer WP, Management of the Mirizzi syndrome and the surgical implications of cholecystcholedochal fistula: Br J Surg, 1990; 77(7); 743-45

4.. Gomez D, Rahman SH, Toogood GJ, Mirizzi’s syndrome – results from a large western experience: HPB (Oxford), 2006; 8(6); 474-79

5.. Beltran MA, Csendes A, Cruces KS, The relationship of Mirizzi syndrome and cholecystoenteric fistula: Validation of a modified classification: World J Surg, 2008; 32(10); 2237-43

6.. Erben Y, Benavente-Chenhalls LA, Donohue JM, Diagnosis and treatment of Mirizzi syndrome: 23-year Mayo Clinic experience: J Am Coll Surg, 2011; 213(1); 114-19 ; discussion 120–21

7.. Johnson LW, Sehon JK, Lee WC, Mirizzi’s syndrome: Experience from a multi-institutional review: Am Surg, 2001; 67(1); 11-14

8.. Chen H, Siwo EA, Khu M, Tian Y, Current trends in the management of Mirizzi syndrome: A review of literature: Medicine (Baltimore), 2018; 97(4); e9691

9.. Lai EC, Lau WY, Mirizzi syndrome: History, present and future development: ANZ J Surg, 2006; 76(4); 251-57

10.. Zaliekas J, Munson JL, Complications of gallstones: The Mirizzi syndrome, gallstone ileus, gallstone pancreatitis, complications of “lost” gallstones: Surg Clin North Am, 2008; 88(6); 1345-68

11.. Beltrán MA, Mirizzi syndrome: History, current knowledge and proposal of a simplified classification: World J Gastroenterol, 2012; 18; 4639-50

12.. Csendes A, Díaz JC, Burdiles P, Mirizzi syndrome and cholecystobiliary fistula: A unifying classification: Br J Surg, 1989; 76(11); 1139-43

13.. Beltran MA, Csendes A, Mirizzi syndrome and gallstone ileus: An unusual presentation of gallstone disease: J Gastrointest Surg, 2005; 9; 686-89

14.. Ibrarullah M, Mishra T, Das AP, Mirizzi syndrome: Indian J Surg, 2008; 70(6); 281-87

15.. Kimura J, Takata N, Lefor AK, Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy for Mirizzi syndrome: A report of a case: Int J Surg Case Rep, 2019; 55; 32-34

16.. Rayapudi K, Gholami P, Olyaee M, Mirizzi syndrome with endoscopic ultra-sound image: Case Rep Gastroenterol, 2013; 7(2); 202-7

17.. Turtel PS, Kreel I, Israel J, Elevated CA19-9 in a case of Mirizzi’s syndrome: Am J Gastroenterol, 1992; 87(3); 355-57

18.. England RE, Martin DF, Endoscopic management of Mirizzi’s syndrome: Gut, 1997; 40(2); 272-76

19.. Johnson AP, Rattigan DA, Pucci MJ, Cholangio-conundrum: A case series of painless jaundice: Case Rep Pancreat Cancer, 2015; 1(1); 16-21

20.. Pelaez-Luna M, Levy MJ, Arora AS, Mirizzi syndrome presenting as painless jaundice: A rare entity diagnosed by EUS: Gastrointest Endosc, 2008; 67(6); 974-75 ; discussion 975

21.. Robertson AG, Davidson BR, Mirizzi syndrome complicating an anomalous biliary tract: A novel cause of a hugely elevated CA19-9: Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2007; 19(2); 167-69

22.. Antoniou SA, Antoniou GA, Makridis C, Laparoscopic treatment of Mirizzi syndrome: A systematic review: Surg Endosc, 2010; 24(1); 33-39

23.. Yasuda I, Itoi T, Recent advances in endoscopic management of difficult bile duct stones: Dig Endosc, 2013; 25(4); 376-85

24.. Baca-Arzaga AA, Navarro-Chávez A, Galindo-Jiménez A, Gallstone lithotripsy with SpyGlass™ system through a cholecystoduodenal fistula in a patient with type IIIa Mirizzi syndrome: Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed), 2021; 86(1); 99-101

25.. Bhandari S, Bathini R, Sharma A, Maydeo A, Usefulness of single-operator cholangioscopy-guided laser lithotripsy in patients with Mirizzi syndrome and cystic duct stones: Experience at a tertiary care center: Gastrointest Endosc, 2016; 84(1); 56-61

26.. Issa H, Bseiso B, Almousa F, Al-Salem AH, Successful treatment of Mirizzi’s syndrome using spyglass guided laser lithotripsy: Gastroenterology Res, 2012; 5(4); 162-66

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Trends of inpatient laboratory studies throughout admission.

Table 1.. Trends of inpatient laboratory studies throughout admission. Table 2.. Classification, descriptions and management of Mirizzi syndrome subtypes.

Table 2.. Classification, descriptions and management of Mirizzi syndrome subtypes. Table 1.. Trends of inpatient laboratory studies throughout admission.

Table 1.. Trends of inpatient laboratory studies throughout admission. Table 2.. Classification, descriptions and management of Mirizzi syndrome subtypes.

Table 2.. Classification, descriptions and management of Mirizzi syndrome subtypes. In Press

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942578

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943801

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942966

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942032

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250