24 September 2022: Articles

Severe Pancytopenia After COVID-19 Revealing a Case of Primary Bone Marrow Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma

Challenging differential diagnosis, Unusual or unexpected effect of treatment, Rare disease, Adverse events of drug therapy, Educational Purpose (only if useful for a systematic review or synthesis)

Yassine KilaniDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.937500

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e937500

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). While bone marrow (BM) involvement is common in lymphoma, primary bone marrow (PBM) DLBCL is extremely rare. We present a case of PBM DLBCL discovered in a patient with COVID-19.

CASE REPORT: An 80-year-old man presented with generalized abdominal pain, weight loss, fever, fatigue, anorexia, and watery diarrhea over a 3-month period. Physical examination was unremarkable. Laboratory workup revealed anemia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated inflammation markers. SARS-COV-2 PCR was positive, while blood cultures were negative. A rapid decline in the white blood cell count in the following days prompted a BM biopsy, confirming the diagnosis of PBM DLBCL. Computed tomography (CT) did not show thoracic or abdominal lymphadenopathy. The patient received packed red blood cell and platelet transfusions, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) for pancytopenia, and empirical antibiotics for suspected infection. Due to active COVID-19 and advanced age, cytotoxic chemotherapy was delayed. Rituximab and prednisone were initiated on day 9, followed by an infusion reaction, which led to treatment discontinuation. He died 2 days later.

CONCLUSIONS: Diagnosing PBM malignancy is challenging, especially with coexisting infection. It is essential to suspect underlying BM malignancy in patients with clinical deterioration and worsening pancytopenia despite adequate treatment. The diagnosis of PBM DLBCL requires the absence of lymphadenopathy, and the presence of histologically confirmed DLBCL. Prompt management with combination chemotherapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) with/without hematopoietic stem cell transplant can improve the prognosis.

Keywords: COVID-19, Lymphoma, Non-Hodgkin, Pancytopenia, rituximab, Aged, 80 and over, Anti-Bacterial Agents, Antineoplastic Combined Chemotherapy Protocols, Bone Marrow, COVID-19, Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor, Humans, lymphadenopathy, Lymphoma, Large B-Cell, Diffuse, Male, Prednisone, SARS-CoV-2, Vincristine

Background

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) accounts for about 4% of cancers diagnosed every year in the United States [1]. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype, accounting for 25% of NHL [1–3]. Genetic alterations in the B cell leukemia or lymphoma 2 (BCL2), BCL6, and MYC genes have been associated with DLBCL [4,5]. Risk factors of DLBCL (and NHL) include chronic immunodeficiency, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection, Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) infection, immunosuppressive therapy, chemotherapeutic agents, radiation, and auto-immune diseases [6–8]. While secondary bone marrow (BM) involvement is common in lymphoma [9], primary bone marrow (PBM) DLBCL is extremely rare [10–13]. We present a case of an 80-year-old man with a recent history of iron deficiency anemia and thrombocytopenia who presented with fever, fatigue, weight loss, chronic diarrhea, and abdominal pain, and was found to have worsening pancytopenia with concurrent COVID-19. The diagnosis of primary bone marrow (PBM) DLBCL was made.

Case Report

HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS:

An 80-year-old man presented with generalized abdominal pain and an undetermined weight loss over a 3-month period. He described his pain as generalized, vague, and unrelated to food intake. He endorsed fevers (but denied night sweats), fatigue, anorexia, and watery diarrhea, over the same time period.

PAST MEDICAL HISTORY:

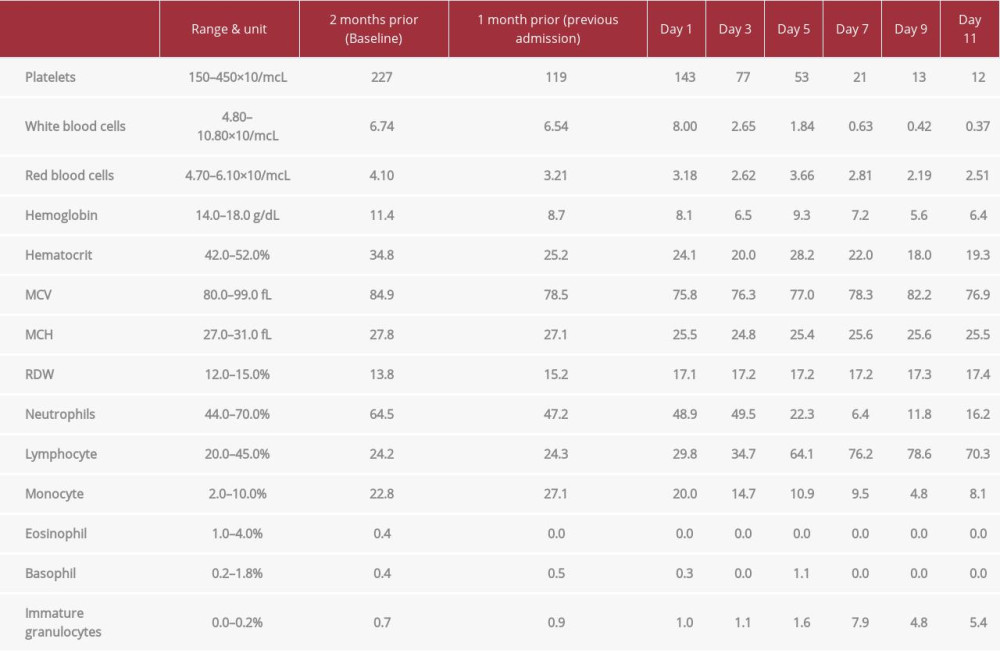

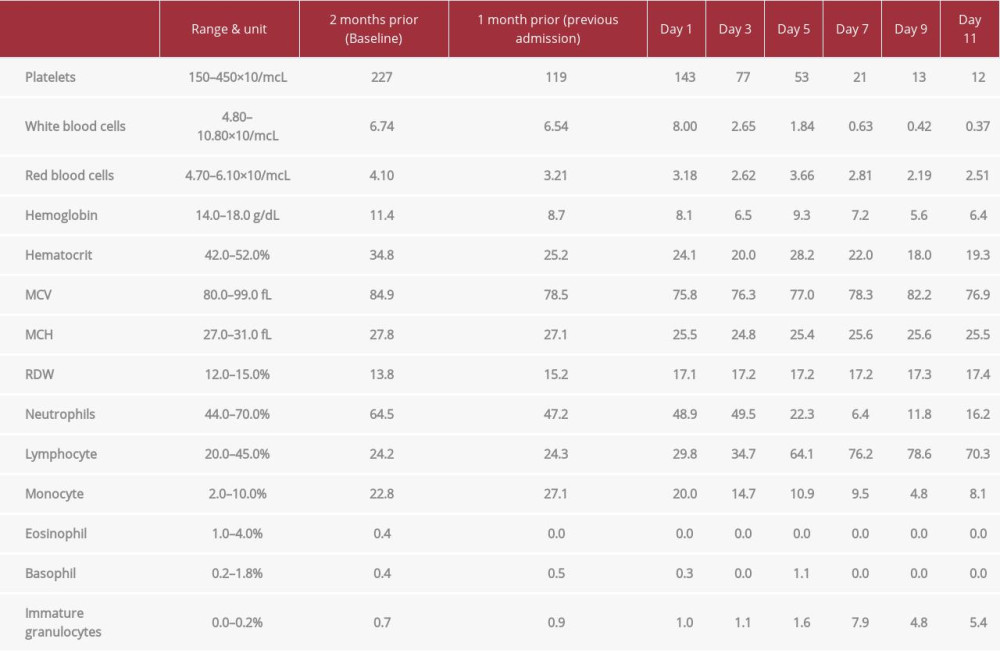

Our patient was a former smoker (he quit 13 years before). He had a past medical history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, major depressive disorder, chronic SIADH likely from Trazodone, and mild chronic normocytic anemia for 20 years. No risk factor of immunodeficiency was reported. Six years prior, diagnostic workup for the anemia, including eso-gastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy, was inconclusive. One month prior, he was admitted in another hospital for iron deficiency anemia and thrombocytopenia (Table 1). A full endoscopic examination was performed and showed an erythematous antral mucosa on EGD, and sessile polyps and hemorrhoids on colonoscopy. Antral histology revealed chronic gastritis with intestinal metaplasia, without evidence of malignancy. Capsule endoscopy of small bowel and computed tomography (CT) enterography were unremarkable. He was discharged with iron supplementation and outpatient follow-up with Hematology.

PHYSICAL EXAM:

On initial evaluation, our patient was afebrile (36.7°C) and tachycardic (110 beats/min), with otherwise normal blood pressure, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation. His weight was 62.2 kg (137.1 lbs.), with a body mass index (BMI) of 21.5 kg/m2, representing a 9.6 kg loss from a previously recorded weight 5 months prior. He appeared cachectic, without scleral icterus. Chest auscultation revealed regular tachycardia without murmurs, with clear lungs on auscultation. The abdomen was soft and nontender, without palpable hepatomegaly or splenomegaly. No peripheral lymphadenopathy, rash, or lower-extremity edema were appreciated.

INVESTIGATIONS:

Laboratory results are summarized in Table 1. A complete blood count (CBC) on day 1 showed bicytopenia with microcytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and a normal white blood cells (WBC) count, with a normal absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 3.92×103/uL, normal lymphocyte count, and eosinopenia. His reticulocyte index was 0.81 (adequate response ≥2). LDH was 2058 U/L (N: 135–225 U/L). An elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) at 207 mg/L (N: <10 mg/dL) and procalcitonin (PCT) at 2.07 (≤0.08 ng/mL) raised the concern for infection. Further workup showed negative blood cultures and fungal testing (1,3 Beta-D-Glucan), and a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR. A rapid decline of the WBC (ANC of 0.13×103/uL) within 5 days of admission raised the concern for a primary bone marrow condition, likely complicated by sepsis secondary to SARS-COV-2 infection. A peripheral smear showed microcytic hypochromic red blood cells (RBCs), nucleated RBCs, and atypical lymphocytes, but no immature cells. BM aspiration and biopsy were performed, and results were obtained on day 9 of admission. Histology revealed DLBCL with more than 90% BM involvement. The residual BM exhibited trilineage maturation, with an overall cellularity 50–80%, a number of blasts <5%, mild diffuse marrow fibrosis (MF-1), and detectable iron storage (Figure 1). Flow cytometry of the BM showed 13% of clonal B cell proliferation with positive Kappa and CD20, and negative CD5 and CD10 (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) revealed >90% of CD20 highlights, without increase in the blast population. A cytogenetic study showed a normal male karyotype (Figure 3). Fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) ruled out c-MYC, BCL-2/IGH (translocation t(14;18)) or BCL-6 rearrangement (Figure 4). A pan CT scan did not reveal lymphadenopathy of significance or any masses/organomegaly, and showed bibasilar atelectasis, without lung infiltrates. The diagnosis of PBM DLBCL was made. HIV 1,2 antigen/antibody test and EBV PCR returned negative. Pre-therapeutic testing for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb), and hepatitis C antibody was negative. The International Prognostic Index (IPI) was 4, predicting a poor prognosis.

TREATMENT AND FOLLOW-UP:

Our patient was initially managed conservatively for COVID-19. He was treated with empirical antibiotics for a suspected bacterial infection. He received 1 unit of packed red blood cell (pRBC), 1 unit of platelets, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) for pancytopenia. Despite these interventions, his clinical condition continued to deteriorate progressively, with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score of 4, progressively worsening altered mental status, and decreasing leukocyte count (Table 1). Once the diagnosis of PBM DLBCL was made on day 9 of admission, the decision was made to treat with a combination chemotherapy, including rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), along with G-CSF. However, given the patient’s active COVID-19 and advanced age, cytotoxic chemotherapy was reserved for a later time. Rituximab (375 mg/m2) and Prednisone 80 mg were started on day 10. Minutes after the first dose of rituximab, the patient developed an infusion reaction. Rituximab was held, and the patient was treated with chlorpheniramine and solumedrol. Further discussions with the patient and his family members led to the decision to keep the patient on palliative care. He was treated with morphine, then became hypotensive despite fluid infusions, and died 2 days after stopping therapy.

Discussion

DLBCL is currently the most common lymphoid neoplasm [14,15], accounting for 25% of NHL worldwide [3,16]. PBM lymphoma is a rare disease, and PBM DLBCL is the most common subtype [10,11,13]. DLBCL has a male predominance, with median ages ranging from 57 to 64 years according to the literature [10,17].

While BM involvement is common in lymphoma [9], PBM DLBCL is extremely rare [10–12]. PBM lymphoma can present with isolated anemia, thrombocytopenia, bicytopenia, or pancytopenia, due to bone marrow infiltration and/or auto-immune destruction [10,18–21]. In a case series by Chang et al of 12 patients with DLBCL, only 1 presented with isolated BM involvement, and most patients initially presented with anemia and thrombocytopenia [10]. In our patient, we believe that the COVID-19 precipitated the pancytopenia; in fact, several cases of COVID-19-induced pancytopenia have been described in the literature, including in patients with underlying hemato-logic malignancy [22–26].

Currently, there are no evidence-based diagnostic criteria for PBM DLBCL. Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning was not performed in our patient. It can be useful for diagnosis, but there are no guidelines for the diagnosis of PBM DLBCL using PET [27]. Several authors have proposed diagnostic criteria for PBM DLBCL. According to Chang et al, the diagnosis requires the absence of lymphadenopathy on whole-body CT scan or physical examination, the presence of histologically confirmed BM involvement with DLBCL, and CD19 or CD20 expression on IHC or flow cytometry [10]. No specific chromosomal abnormalities or other CD markers have been associated with PBM DLBCL [12,28]. CD5 expression in PBM DLBCL is variable in the literature, ranging from 0% to 80% of PBM DLBCL cases [5,10,12,28], and its clinical significance remains uncertain. CD30 was seen in 25% and carries a favorable prognosis [5].

Several reports showed complete remission of PBM DLBCL following chemotherapy with R-CHOP with/without hematopoietic stem cell transplant [10,27,29,30]. Almost all cases of PBM DLBCL have a high IPI, predicting low survival rates [31,32]. The median survival was found to be less than 9 months [31].

Our patient had a 1-month history of bicytopenia, and presented with worsening pancytopenia following COVID-19, likely due to reduced BM reserve caused by the PBM DLBCL. The diagnosis of PBM DLBCL was made, and our patient tested negative for HIV and EBV. He had a high IPI score, indicating a poor prognosis. Following an infusion reaction to rituximab, the treatment was held, and he died a few days later from a cardiac arrest.

Conclusions

The diagnosis of PBM DLBCL can be challenging, especially in patients with concomitant infection. In cases of clinical deterioration and worsening pancytopenia despite adequate management, clinicians should have high clinical suspicion of BM malignancy and perform a prompt diagnostic workup for PBM malignancy. PBM DLBCL is an aggressive malignancy, but the prognosis improves with timely management with rituximab-based chemotherapy and/or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Figures

References:

1.. Thandra KC, Barsouk A, Saginala K, Epidemiology of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: Med Sci (Basel), 2021; 9(1); 5

2.. Miranda-Filho A, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Global patterns and trends in the incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Cancer Causes Control, 2019; 30(5); 489-99

3.. Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992–2001: Blood, 2006; 107(1); 265-76

4.. Colomo L, López-Guillermo A, Perales M, Clinical impact of the differentiation profile assessed by immunophenotyping in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Blood, 2003; 101(1); 78-84

5.. Hu S, Xu-Monette ZY, Balasubramanyam A, CD30 expression defines a novel subgroup of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with favorable prognosis and distinct gene expression signature: A report from the International DLBCL Rituximab-CHOP Consortium Program Study: Blood, 2013; 121(14); 2715-24

6.. Sapkota S, Shaikh H, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. [Updated 2021 Dec 5]: StatPearls [Internet] Jan, 2022, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559328/

7.. Grogg KL, Miller RF, Dogan A, HIV infection and lymphoma: J Clin Pathol, 2007; 60(12); 1365-72

8.. Thorley-Lawson DA, Gross A, Persistence of the Epstein-Barr virus and the origins of associated lymphomas: N Engl J Med, 2004; 350(13); 1328-37

9.. Conlan MG, Bast M, Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD, Bone marrow involvement by non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: The clinical significance of morphologic discordance between the lymph node and bone marrow. Nebraska Lymphoma Study Group: J Clin Oncol, 1990; 8(7); 1163-72

10.. Chang H, Hung YS, Lin TL, Primary bone marrow diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A case series and review: Ann. Hematol, 2011; 90; 791-96

11.. Gatter KC, Warnke RA, Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: In: Tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, 2001; 171-74, Lyon, France, IARC Press

12.. Alvares CL, Matutes E, Scully MA, Isolated bone marrow involvement in diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A report of three cases with review of morphological, immunophenotypic and cytogenetic findings: Leuk Lymphoma, 2004; 45(4); 769-75

13.. Martinez A, Ponzoni M, Agostinelli C, Primary bone marrow lymphoma: An uncommon extranodal pre- sentation of aggressive non-hodgkin lymphomas: Am J Surg Pathol, 2012; 36; 296-304

14.. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A, Cancer statistics, 2017: Cancer J Clin, 2017; 67; 7-30

15.. Armitage JO, Gascoyne RD, Lunning MA, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Lancet, 2017; 390; 298-310

16.. van Leeuwen MT, Turner JJ, Lymphoid neoplasm incidence by WHO subtype in Australia 1982–2006: Int J Cancer, 2014; 135(9); 2146-56

17.. Shi Y, Han Y, Yang J, Clinical features and outcomes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma based on nodal or extranodal primary sites of origin: Analysis of 1,085 WHO classified cases in a single institution in China: Chin J Cancer Res, 2019; 31(1); 152-61

18.. Kagoya Y, Sahara N, Matsunaga T, A case of primary bone marrow B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with severe thrombocytopenia: Case report and a review of the literature: Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus, 2010; 26(3); 106-8

19.. Lapa C, Knott M, Rasche L, Primary bone marrow diffuse large B-cell lymphoma affecting distal parts of the legs as a cause of persisting B symptoms: Eur J Haematol, 2014; 93(6); 545-46

20.. Sandeep , Sharma P, Ahluwalia J, Primary bone marrow T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma: A diagnostic challenge: Hematology, 2013; 18(2); 85-88

21.. Níáinle F, Hamnvik OP, Gulmann C, Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with isolated bone marrow involvement presenting with secondary cold agglutinin disease: Int J Lab Hematol, 2008; 30(5); 444-45

22.. Bridwell RE, Inman BL, Birdsong S, A coronavirus disease-2019 induced pancytopenia: Am J Emerg Med, 2021; 47; 324.e1-e3

23.. Barranco-Trabi JJ, Minns R, Akter R, Case report: COVID associated pancytopenia unmasking previously undiagnosed pernicious anemia: Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2022 [Online ahead of print]

24.. Wu K, Dansoa Y, Pathak P, Pancytopenia with development of persistent neutropenia secondary to COVID-19: Case Rep Hematol, 2022; 2022; 8739295

25.. Velier M, Priet S, Appay R, Severe and irreversible pancytopenia associated with SARS-CoV-2 bone marrow infection in a patient with walden-strom macroglobulinemia: Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk, 2021; 21(6); e503-5

26.. Sharma N, Shukla R, Warrier R, Pancytopenia secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection – a case report: SN Compr Clin Med, 2022; 4(1); 31

27.. Hishizawa M, Okamoto K, Chonabayashi K, Primary large B-cell lymphoma of the bone marrow: Br J Haematol, 2007; 136(3); 351

28.. Hu Y, Chen SL, Huang ZX, Case report diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the primary bone marrow: Genet Mol Res, 2015; 14(2); 6247-50

29.. Kazama H, Teramura M, Yoshinaga K, Long-term remission of primary bone marrow diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with high-dose chemotherapy rescued by in vivo rituximab-purged autologous stem cells: Case Rep Med, 2012; 2012; 957063

30.. Nishida H, Suzuki H, Hori M, Obara K, Primary isolated bone marrow diffuse large B cell lymphoma with long-term complete remission: Leuk Res Rep, 2018; 10; 11-15

31.. Kajiura D, Yamashita Y, Mori N, Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma initially manifesting in the bone marrow: Am J Clin Pathol, 2007; 127(5); 762-69

32.. , A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: N Engl J Med, 1993; 329(14); 987-94

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Complete blood count (CBC). The bicytopenia found at the patient’s previous admission progressed into pancytopenia in the setting of COVID-19. Note that the patient had normocytic anemia and thrombocytopenia 1 month prior to admission.

Table 1.. Complete blood count (CBC). The bicytopenia found at the patient’s previous admission progressed into pancytopenia in the setting of COVID-19. Note that the patient had normocytic anemia and thrombocytopenia 1 month prior to admission. Table 1.. Complete blood count (CBC). The bicytopenia found at the patient’s previous admission progressed into pancytopenia in the setting of COVID-19. Note that the patient had normocytic anemia and thrombocytopenia 1 month prior to admission.

Table 1.. Complete blood count (CBC). The bicytopenia found at the patient’s previous admission progressed into pancytopenia in the setting of COVID-19. Note that the patient had normocytic anemia and thrombocytopenia 1 month prior to admission. In Press

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942770

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943214

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943010

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943687

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250