19 December 2022: Articles

A Case Report of Listeria Meningitis with Severe Rhabdomyolysis and Normal Renal Function

Unusual clinical course, Challenging differential diagnosis, Unusual or unexpected effect of treatment, Diagnostic / therapeutic accidents, Unexpected drug reaction

Mina Sourial1EF*, Sumit Kapoor12EF, Manoj Karwa1EFDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.938024

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e938024

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Listeria monocytogenes is known to cause meningitis, bacteremia, and rhabdomyolysis, typically associated with acute kidney injury. We present the case of a young woman who developed severe rhabdomyolysis without kidney failure in the setting of listeriosis.

CASE REPORT: A 22-year-old woman with a past medical history of type 1 diabetes mellitus presented with fever, headache, and vomiting. Initial blood work revealed a white blood cell count of 22 K/µL, creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level of 275 U/L, blood urea nitrogen of 9 mg/dL, and creatinine of 0.89 mg/dL. A lumbar puncture (LP) was performed and was positive for Listeria monocytogenes. Her initial point-of-care ultrasound demonstrated hyperdynamic left ventricular (LV) function. Although she was immediately started on empiric coverage for bacterial and viral meningitis with intravenous vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and acyclovir, the antimicrobial regimen was changed to ampicillin and gentamicin after the LP results were obtained. On the second hospital day, a repeat echocardiogram demonstrated a dilated LV with severely reduced function with an ejection fraction (EF) of 30%. Her CPK increased and peaked at 299 637 U/L by day 6. Despite the low EF and elevated CPK, her kidney function remained at baseline at all times. Her EF improved to 60% by hospital day 20. She received large volumes of intravenous fluids, completed a 3-week course of ampicillin, continued to improve, and was discharged to a rehabilitation facility with no deficits.

CONCLUSIONS: Listeria infection can be associated with severe rhabdomyolysis, which is usually associated with kidney dysfunction. Administration of large volumes of intravenous fluids may decrease this likelihood.

Keywords: Acute Kidney Injury, Listeria monocytogenes, Meningitis, Bacterial, rhabdomyolysis, Female, Humans, young adult, Adult, Meningitis, Listeria, Ampicillin, Vancomycin, Kidney

Background

Case Report

A 22-year-old woman with a past medical history of poorly controlled type 1 diabetes mellitus presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with a 5-day history of fever, headache, nausea, and vomiting. Three days prior to presentation, she had been prescribed sumatriptan 50 mg as needed for presumed migraine headache at an outside facility. Her other home mediations were Ademalog insulin, insulin glargine, and lisinopril 2.5 mg oral daily. She never smoked, drank alcohol, or used illicit substances. She had not travel internationally in the preceding 6 months prior to presentation. Of note, she had purchased 2 cockatiel birds 6 months prior to presentation.

In the ED, her vital signs were as follows: temperature 39.2°C, pulse 123 beats per minute, respiratory rate 22 per minute, blood pressure 131/75 mmHg, and oxygen saturation 100% on room air. She was confused, aphasic, had nuchal rigidity, and right upper-extremity paresis. She had negative Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs and no papilledema. Her initial labs included a white blood cell (WBC) count of 22 K/µL, hemoglobin 13.8 g/dL, sodium 129 mEq/L, potassium 4 mEq/L, chloride 100 mEq/L, bicarbonate 13 mEq/L, blood urea nitrogen 9 mg/dL, creatinine 0.89 mg/dL, initial creatine phosphokinase 275 U/L, lactic acid 2.5 mmol/L. Her hemoglobin A1c was 13.3%. The urine toxicology screen was negative. Her initial electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia at 120 beats per minute.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head was performed and was noncontributory. The patient was immediately started on empiric coverage for bacterial and viral meningitis with vancomycin 1 gram intravenous (IV) twice daily, ceftriaxone 2 gram IV every 12 hours, and acyclovir 600 milligrams IV every 8 hours. She also received 3 liters of isotonic fluids in the ED. A lumbar puncture (LP) was performed and noted to be cloudy in appearance, with WBC count of 2790 cells/µL, 75% segmented neutrophils, total protein 163 mg/dL, and glucose 31 mg/dL.

Within 7 hours, the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) meningitis/encephalitis polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panel was positive for

The patient was admitted to the medical intensive care unit (MICU) for continued management of Listeria meningitis and diabetic ketoacidosis. She received an additional 4 liters of iso-tonic fluids when she was in the MICU. Her initial point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) on hospital day 1 was consistent with a hyperdynamic left ventricular (LV) function. However, on the second hospital day, a repeat echocardiogram noted a dilated and severely reduced LV function with an ejection fraction (EF) of 30% (Figure 1, Video 1). The patient’s alertness and aphasia continued to wax and wane. On hospital day 3, the patient had an 8-channel mobile electroencephalogram (EEG) followed by a 24-channel continuous bedside video-EEG, neither of which revealed any seizure activity. On the fourth hospital day, the patient’s urine was noted to be dark and discolored, and a repeat CPK level was noted to be 27 131 U/L. CPK levels continued to rise and, on hospital day 6, peaked at 299 637 U/L. Serum aldolase levels were monitored and peaked at 1104 U/L on hospital day 6. Despite such elevated CPK and aldolase levels, she remained non-oliguric and her creatinine remained at baseline. A workup of the patient’s rhabdomyolysis included a full rheumatological panel that was unrevealing for any form of inflammatory myositis. The ICU course was further complicated by septic shock, acute respiratory failure, and new seizure on hospital day 6. This necessitated intubation, invasive mechanical ventilation, and vasopressor support. An 8-channel mobile EEG was performed immediately after treating the seizure with intravenous propofol and levetiracetam, which did not show any further seizures. On hospital days 6 through 9, continuous monitoring for seizure activity with a 24-channel continuous EEG did not show any seizure activity. A muscle biopsy was deferred since CPK levels started to decline with IV fluids. During the first 10 days of her hospitalization, she received approximately 49 liters of fluids (including tube feeds while she was on mechanical ventilation). She required vasopressor support with norepinephrine drip for treatment of septic shock secondary to Listeria bacteremia until hospital day 11. She continued receiving treatment with ampicillin 2 grams every 4 hours IV in addition to other antimicrobials for methicillin-resistant

The patient’s mental status continued to improve. She was subsequently liberated from mechanical ventilation on hospital day 14. On hospital day 18, she was transferred from the MICU to the internal medicine ward service. On hospital day 19, she was noted to be tachycardic and short of breath. A CT angio-gram of the chest revealed a right lower-lobe pulmonary embolism, and transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed a right atrial thrombus. A repeat echocardiogram on hospital day 20 showed recovery of LV function with an EF of 60% and normal LV size (Figure 2, Video 2). On hospital day 20, she underwent interventional radiology-guided thrombectomy using an endovascular device. She was started on a heparin intravenous infusion. She was observed in the MICU until hospital day 22, when she was sent to the internal medicine ward for continued care.

The patient completed a 3-week course of ampicillin. Her mental status continued to improve with return of normal motor function with no recurrence of seizures. She was discharged to a rehabilitation facility on hospital day 23 on apixaban and levetiracetam with no residual neurological deficits.

Discussion

We report a case of Listeria meningitis and bacteremia with severe rhabdomyolysis in a young woman with normal renal function. The etiology of our patient’s listeriosis was most likely food-borne community exposure in the setting of an immunocompromised state secondary to her poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. Our case is unique in several ways. First, our patient developed severe rhabdomyolysis without developing acute kidney injury (AKI).

Rhabdomyolysis is usually characterized as a breakdown of muscle fibers and the leakage of muscle cell contents, including electrolytes, myoglobin, and other proteins (CPK, lactate dehydrogenase, aldolase) into the circulation [8]. The etiology could be related to trauma, strenuous exercise, drug or toxin exposure, metabolic disorders, and infections [8]. Infections only account for 5% of all cases of rhabdomyolysis [9]. Rhabdomyolysis is noted in both bacterial (pyomyositis, Legionella, Listeria) and viral infections (influenza A and B, parainfluenza, herpes simplex virus, Epstein-Barr virus, coxsackievirus, cytomegalovirus, human immunodeficiency virus, adenovirus) [9].

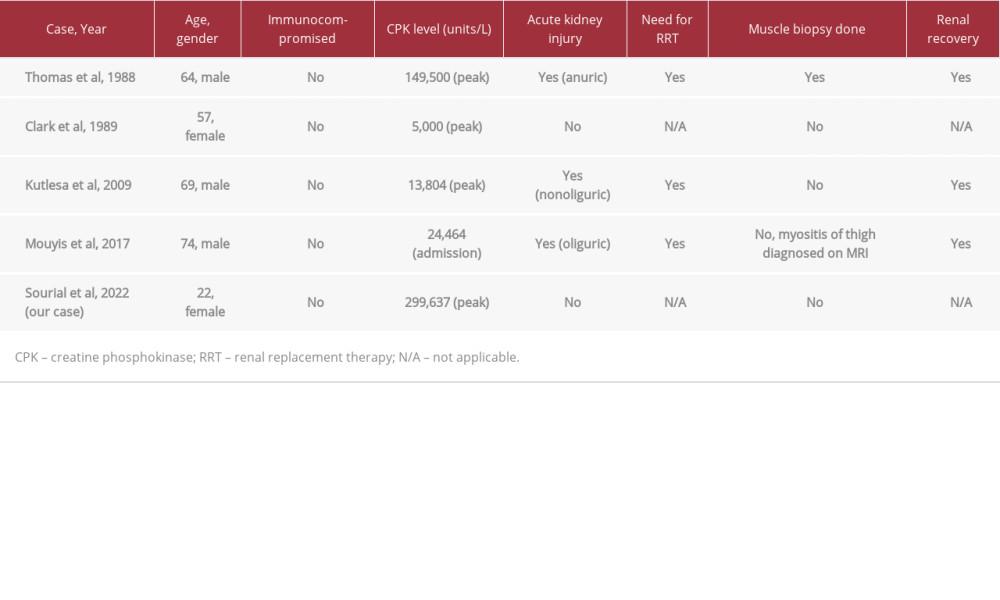

Thomas and colleagues first reported the association of Listeria meningitis with severe rhabdomyolysis and AKI in 1988 [7]. Since then, only 3 additional cases of Listeria meningitis associated with rhabdomyolysis have been described in the literature [9–11]. Table 1 provides a summary of these case reports, including our case. The reported CPK levels ranged from 5000 to 149 500 U/L. The pathogenesis of rhabdomyolysis in Listeria infection is likely due to direct invasion and toxic degeneration of muscle fibers [9]. Patients usually develop severe rhabdomyolysis and myoglobinuria. Precipitation of myoglobin in the renal tubules leads to tubular obstruction, resulting in acute tubular necrosis (ATN). Patients with severe AKI may require renal replacement therapy (RRT). Except for the Clark et al study, with a peak CPK level of 5000 U/L, all other cases of Listeria meningitis and rhabdomyolysis were associated with AKI and the need for RRT. The prognosis of AKI was good, as all of the patients in the reports mentioned were able to discontinue RRT.

Of the documented cases (Table 1), our patient had the highest CPK level (299 637 U/L) so far without developing AKI. This may have been due to early and aggressive fluid management, which prevented tubular obstruction and development of AKI. Figure 3 demonstrates the trend of her CPK alongside her daily urine output. As her CPK peaked, her urine output increased with continued IV fluid hydration. As mentioned previously, she had received approximately 49 liters of fluids in the first 10 days of hospitalization. The severely elevated CPK level of our patient was attributed to rhabdomyolysis due to Listeria infection as there was no evidence of trauma, metabolic disorder, or drug or toxin exposure. A muscle biopsy was not indicated due to rapid improvement of her CPK with continued IV fluid hydration and confirmed diagnosis of Listeria monocytogenes by blood and CSF cultures.

Second, we report the first case of the association of Listeria meningitis infection with septic cardiomyopathy. Septic cardiomyopathy was first described by Parker et al in 1984 as a reversible myocardial depression in patients with septic shock [9]. It is characterized by left ventricular dilatation, depressed ejection fraction, and recovery in 7–10 days [11]. Our patient developed a severely reduced ejection fraction of 25–30%, which returned to normal as her infection improved. One the complications this patient experienced was a right atrial thrombus (RAT), which was likely secondary to a left internal jugular vein central venous catheter. As a result of the RAT, it is possible that part of the thrombus became dislodged and resulted in a pulmonary embolism (PE).

Third, our patient had close contact with 2 cockatiel birds that she cared for at home for 6 months. Listeriosis has been reported in ruminant animals such as cattle, sheep, goat, and in a variety of birds, including cockatiels (

One limitation of our case report is that we did not perform a muscle biopsy to rule out inflammatory myositis since the patient’s CPK levels trended down.

Conclusions

Figures

References:

1.. Schlech WF: Microbiol Spectr, 2019; 7(3); G3-0014-2018

2.. Rogalla D, Bomar PA: Listeria monocytogenes Jul 4, 2022, StatPearls [Internet]

3.. Geerlings SE, Hoepelman AI, Immune dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM): FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol, 1999; 26(3–4); 259-65

4.. Thomas F, Ravaud Y: J Infect Dis, 1988; 158(2); 492-93

5.. Clark P, Lough M, Whiting B, Rhabdomyolysis and listeria monocytogenes: Scott Med J, 1989; 34(4); 503

6.. Kutlesa M, Lepur D, Bukovski S, Lepur NK, Barsić B: Neurocrit Care, 2009; 10(1); 70-72

7.. Mouyis K, Ali S, Corcoran JP, Misra A, Listeria infection presenting as myositis and rhabdomyolysis, needing renal replacement: Br J Hosp Med (Lond), 2017; 78(12); 722-23

8.. Shivaprasad HL, Kokka R, Walker RL: Avian Dis, 2007; 51(3); 800-4

9.. Parker MM, Shelhamer JH, Bacharach SL, Profound but reversible myocardial depression in patients with septic shock: Ann Intern Med, 1984; 100(4); 483-90

10.. Bosch X, Poch E, Grau JM, Rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury: N Engl J Med, 2009; 361(1); 62-72 Erratum in: . 2011;364(20):1982

11.. Sato R, Nasu M, A review of sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy: J Intensive Care, 2015; 3; 48

Figures

In Press

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942578

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943801

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942966

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942032

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250