30 June 2020: Articles

A Surviving Case of Acanthamoeba Granulomatous Amebic Encephalitis in a Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipient

Challenging differential diagnosis, Unusual or unexpected effect of treatment

Niamh A. Keane1DEF*, Louise Marie Lane2C, Emma Canniff3BC, Daniel Hare4D, Simon Doran3BD, Eugene Wallace5E, Siobhan Hutchinson6B, Marie-Louise Healy7E, Brian Hennessy8BC, Jim Meaney3D, Peter Chiodini9D, Brian O’Connell4D, Alan Beausang2CD, Elisabeth Vandenberghe1EFDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.923219

Am J Case Rep 2020; 21:e923219

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Acanthamoeba are free-living amoebae with potential to infect immunocompromised hosts. The mortality rate of granulomatous amebic encephalitis (GAE) due to Acanthamoeba exceeds 90% and there are currently no reports of survival of this infection in recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

CASE REPORT: We report herein the case of a 32-year-old man presenting to our service with abrupt neurological deterioration and seizures 5 months after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for Hodgkin lymphoma. Clinical and imaging findings were non-specific at presentation. Multiple circumscribed, heterogenous, mass-like lesions were identified on MRI. Brain biopsy was performed and revealed multiple cysts and trophozoites suggesting a diagnosis of granulomatous amebic encephalitis. PCR testing confirmed Acanthamoeba. Treatment with miltefosine, metronidazole, azithromycin, fluconazole, pentamidine isethionate, and co-trimoxazole was instituted and the patient survived and shows continued improvement with intensive rehabilitation.

CONCLUSIONS: We report the first successful outcome in this setting. The diagnosis would have been missed on cerebrospinal fluid analysis alone, but was rapidly made by histological analysis of brain biopsy. This diagnostically challenging infection is likely under-recognized. Early brain biopsy and commencement of a prolonged miltefosine-containing anti-ameba regimen can be curative.

Keywords: Acanthamoeba, Amoeba, Central Nervous System Protozoal Infections, Amebiasis, Antiprotozoal Agents, Brain, Drug Therapy, Combination, Granuloma, Immunocompromised Host, Infectious Encephalitis, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, transplant recipients

Background

Granulomatous amebic encephalitis is a rare central nervous system infection that is usually rapidly fatal [1,2]. Symptoms are myriad, and reflect the area of brain infected. Typically, the onset of symptoms is insidious until overwhelming infection results in rapid severe neurological decline, including seizures, altered levels of consciousness, coma, and death. Diagnosis is challenging due to the non-specific clinical presentation and radiological features. Brain biopsy is generally required for diagnosis, with cerebrospinal fluid analysis and culture yielding false-negative results in the majority of cases [2]. The optimal treatment for this infection has not been described. Herein, we report a case in which diagnosis was promptly made by early brain biopsy and a prolonged combination anti-amebic treatment approach was instituted with successful outcome.

Case Report

A 32-year-old male engineer presented 5 months after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant for chemotherapy-refractory Hodgkin lymphoma with a 4-day history of headache, difficulty finding words, and unable to read back cell phone texts which he had just completed. Collateral history confirmed he had driven through a red light he did not notice, and noted episodes of staring with speech arrest. Neurological examination confirmed anomic aphasia with compensatory circumlocution, and alexia without agraphia (unable to read despite retaining the ability to write). Visual field testing revealed right homonymous superior quadrantanopia.

He was diagnosed 2 years prior to this presentation with stage IVB classical Hodgkin lymphoma and international prognostic score (IPS) of 5. Interim positron emission tomography (PET) following 2 cycles of Adriamycin, Bleomycin, Vinblastine, and Dacarbazine (ABVD) chemotherapy was Deauville score 4, and treatment was intensified to the dose-escalated Bleomycin Etoposide Adriamycin Cyclophosphamide Oncovin Procarbazine Prednisolone (BEACOPP) regimen for 2 cycles, resulting in a persistent Deauville 4 score. The patient received salvage therapy with Brentuximab vedotin and Ifosfamide Carboplatin Etoposide (ICE) for 3 cycles, achieving a complete remission (Deauville score 1) which was consolidated with a matched unrelated allograft using Carmustine/BCNU Etoposide Cytarabine Melphalan (BEAM) and Alemtuzumab conditioning. He engrafted on day 12 and his post-transplant course was complicated by steroid-responsive grade 3 skin graft versus host disease. The patient was PET-negative and a 100% total and CD3 donor chimera on day 100.

At the time of this acute neurological presentation on day 160, he remained profoundly immunosuppressed. His medication consisted of valaciclovir 500 mg once daily, atovaquone 750 mg twice daily, phenoxymethylpenicillin 333 mg twice daily, prednisolone 10 mg once daily (for skin graft versus host disease), and ciclosporin 50mg twice daily. He reported adherence to all medications. His absolute lymphocyte count was 0.1×109/L with absolute CD4+ T cell count 51×106/L.

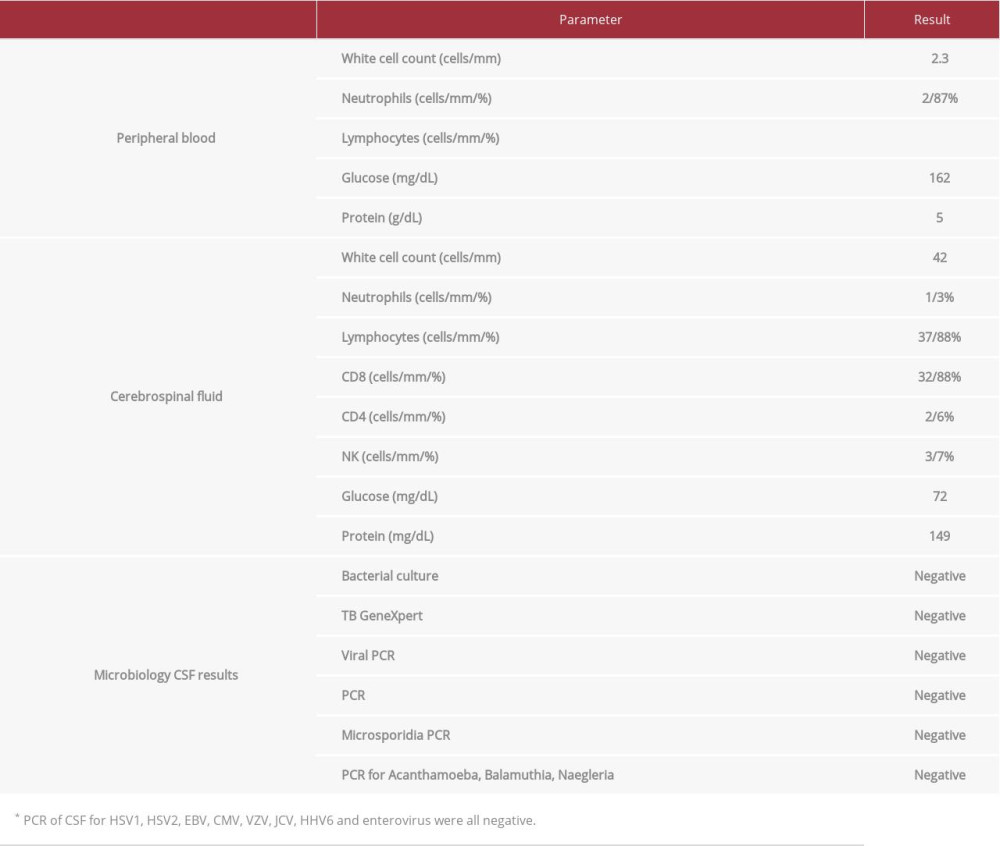

MRI brain revealed multiple circumscribed heterogenous mass-like lesions in the left occipital and right frontal lobes, with further areas of edema in the splenium of the corpus callosum and left temporal lobe, which correlated with his alexia without agraphia and right superior quadrantanopia, respectively (Figure 1A). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed elevated white cell count of 42/mm3 (reference 0–5 WBC/mm3) and elevated protein 1.49 mg/dL (reference 0.15–0.45g/L) (Table 1). CSF microscopy was negative. The patient was rapidly deteriorating neurologically, and electroencephalogram was not possible, but an urgent brain biopsy was performed. The histological features were consistent with GAE, with

The

The patient deteriorated abruptly on day 9 of admission (day 5 of anti-amoebic therapy). Episodes of speech arrest became more frequent and he became disoriented to place and time. On day 8 of admission, serum sodium had been 139 mEq/L (139 mmol/L) (reference range 136–145 mEq/L, 136–145 mmol/L). On the evening of day 9, this fell to 129 mEq/L (129 mmol/L) in tandem with worsening symptomatology. Eslicarbazepine 400 mg qd and clobazam 5 mg bid anticonvulsant therapy was added, but on day 10, the patient had a generalized tonic-clonic seizure associated with a precipitous fall in serum sodium to 110 mmol/L. He was treated with hypertonic (3%) saline with temporary omission of other infusions, including pentamidine isethionate, given its potential to aggravate hyponatremia. Repeat MRI brain revealed significantly worsened vasogenic edema with resultant mass effect (Figure 1B). Risk of transforaminal herniation was deemed to be high based on the imaging, and dexamethasone 8 mg tid IV was instituted to ameliorate edema. Clinical and laboratory parameters were consistent with Syndrome of Inappropriate Anti-Diuretic Hormone secretion (SIADH) as a cause of this abrupt severe hyponatremia – the onset was 9 days after brain biopsy; serum osmolarity was 280 mmol/kg and urinary osmolarity and sodium were both inappropriately high at 556 mmol/kg and 178 mmol/L, respectively. The patient responded to hypertonic saline, with normalization of serum sodium and correction of both urinary osmolarity and sodium over the course of 11 days.

In total, our patient was hospitalized for 53 days. Increasing nausea limited tolerance of the anti-amebic regimen and in total he completed 21 days of pentamidine isethionate, 28 days of co-trimoxazole and azithromycin, 60 days of metronidazole, 120 days of fluconazole, and 150 days of miltefosine. Maintenance therapy of miltefosine 50 mg 3 times weekly was planned but discontinued because of gastrointestinal intolerance. CSF re-analysis on day 40 indicated normalization of cell count and protein. Repeat MRI at this time showed persistent decreased gyral enhancement, widespread edema, and areas of parenchymal necrosis. Repeat imaging on day 140 demonstrated resolution of edema and ex-vacuo dilatation of the posterior horn of the left lateral ventricle with surrounding gliosis, consistent with the natural history of treated necrotic areas (Figure 1C).

Persistent language deficits, including anomic aphasia and alexia, on discharge from hospital reflected left temporoparietal and callosal injuries. He underwent an outpatient neuro-rehabilitation program, with significant improvement in attention and recall. At 12 months after presentation, he is performing well in language and reading, with minor residual difficulty in naming low-frequency items, but improved fluency and fewer word-finding pauses. He displays excellent procedural memory for complex skills learned previously including engine repair, which he has resumed as a hobby. Our patient shows ongoing improvement and remains in complete remission 1 year after transplant for Hodgkin lymphoma.

Discussion

Granulomatous amoebic encephalitis (GAE) is a rare central nervous system infection caused by free-living amoebae and is associated with a high mortality rate. Three genera of pathogenic free-living amoebae are known to infect human hosts:

The source of the Acanthamoeba infection was not obvious in the case reported herein. Our patient previously used disposal contact lenses for correction of myopia but ceased using them prior to undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and had no symptoms or signs of keratitis.

The optimal approach to the management of

Our patient is the first reported case of survival following acanthamebic GAE in the setting of profound immunosuppression after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Prompt biopsy and institution of an appropriate miltefosine-containing regimen led to a successful outcome following a prolonged treatment course and intensive rehabilitation.

Conclusions

This case illustrates the importance of early brain biopsy in a profoundly immunosuppressed patient with unexplained neurological deterioration, as the diagnosis would not have been made if relying on CSF analysis alone. Granulomatous amebic encephalitis is a rapidly fatal infection that is likely under-recognized. Early recognition and prompt institution of appropriate miltefosine-containing anti-amebic regimen can secure a successful outcome, even in profoundly immunosup-pressed patients.

Figures

References:

1.. Siddiqui R, Khan NA, Biology and pathogenesis of Acanthamoeba: Parasit Vectors, 2012; 5; 6

2.. Schuster FL, Visvesvara GS, Opportunistic amoebae: Challenges in prophylaxis and treatment: Drug Resist Updat, 2004; 7(1); 41-51

3.. Anderlini P, Przepiorka D, Luna M, Acanthamoeba meningoencephalitis after bone marrow transplantation: Bone Marrow Transplant, 1994; 14(3); 459-61

4.. Feingold JM, Abraham J, Bilgrami S, Acanthamoeba meningoencephalitis following autologous peripheral stem cell transplantation: Bone Marrow Transplant, 1998; 22(3); 297-300

5.. Castellano-Sanchez A, Popp AC, Nolte FS, Acanthamoeba castellani encephalitis following partially mismatched related donor peripheral stem cell transplantation: Transpl Infect Dis, 2003; 5(4); 191-94

6.. Peman J, Jarque I, Frasquet J, Unexpected postmortem diagnosis of Acanthamoeba meningoencephalitis following allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation: Am J Transplant, 2008; 8(7); 1562-66

7.. Akpek G, Uslu A, Huebner T, Granulomatous amebic encephalitis: An under-recognized cause of infectious mortality after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Transpl Infect Dis, 2011; 13(4); 366-73

8.. Doan N, Rozansky G, Nguyen HS, Granulomatous amebic encephalitis following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Surg Neurol Int, 2015; 6(Suppl. 18); S459-62

9.. Coven SL, Song E, Steward S, Acanthamoeba granulomatous amoebic encephalitis after pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant: Pediatr Transplant, 2017; 21(8); e13060

10.. Kaul DR, Lowe L, Visvesvara GS, Acanthamoeba infection in a patient with chronic graft-versus-host disease occurring during treatment with voriconazole: Transpl Infect Dis, 2008; 10(6); 437-41

11.. Abd H, Saeed A, Jalal S, Bekassy AN, Sandstrom G, Ante mortem diagnosis of amoebic encephalitis in a haematopoietic stem cell transplanted patient: Scand J Infect Dis, 2009; 41(8); 619-22

12.. Alsam S, Kim KS, Stins M, Acanthamoeba interactions with human brain microvascular endothelial cells: Microb Pathog, 2003; 35(6); 235-41

13.. Khan NA, Siddiqui R, Acanthamoeba affects the integrity of human brain microvascular endothelial cells and degrades the tight junction proteins: Int J Parasitol, 2009; 39(14); 1611-16

14.. Sissons J, Alsam S, Goldsworthy G, Identification and properties of proteases from an Acanthamoeba isolate capable of producing granulomatous encephalitis: BMC Microbiol, 2006; 6; 42

15.. Ong TYY, Khan NA, Siddiqui R, Brain-eating amoebae: Predilection sites in the brain and disease outcome: J Clin Microbiol, 2017; 55(7); 1989-97

16.. Dorlo TP, Balasegaram M, Beijnen JH, de Vries PJ, Miltefosine: A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of leishmaniasis: J Antimicrob Chemother, 2012; 67(11); 2576-97

17.. Schuster FL, Guglielmo BJ, Visvesvara GS: J Eukaryot Microbiol, 2006; 53(2); 121-26

18.. Aichelburg AC, Walochnik J, Assadian O: Emerg Infect Dis, 2008; 14(11); 1743-46

19.. Webster D, Umar I, Kolyvas G, Treatment of granulomatous amoebic encephalitis with voriconazole and miltefosine in an immunocompetent soldier: Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2012; 87(4); 715-18

20.. Brondfield MN, Reid MJ, Rutishauser RL, Disseminated Acanthamoeba infection in a heart transplant recipient treated successfully with a miltefo-sine-containing regimen: Case report and review of the literature: Transpl Infect Dis, 2017; 19(2); e12661

Figures

In Press

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942770

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943214

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943010

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943687

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250