11 March 2023: Articles

Heidenhain Variant of Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease with a Variety of Visual Symptoms: A Case Report with Autopsy Study

Challenging differential diagnosis, Rare disease

Yoshio Hisata12ABDEF, Shun Yamashita1ABDEF*, Masaki Tago1ABDEF, Motoi Yoshimura3CDF, Tomotaro Nakashima4ABDF, Tomoyo M. Nishi1ABF, Yoshimasa Oda5ABF, Hiroyuki Honda3CDF, Shu-ichi Yamashita1DEFDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.938654

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e938654

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) is a fatal disease caused by the change of prion protein (PrP). Affected patients present with rapidly progressive cognitive dysfunction, myoclonus, or akinetic mutism. Diagnosing the Heidenhain variant of sCJD, which initially causes various visual symptoms, can be particularly difficult.

CASE REPORT: A 72-year-old woman presented with a 2- to 3-month history of photophobia, blurring vision in both eyes. Seven days previously, she showed visual impairment of 20/2000 in both eyes. Left homonymous hemianopia and restricted downward movement of the left eye were observed with an intact pupillary light reflex and normal fundoscopy. On admission, her visual acuity was light perception. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging revealed no abnormality, and electroencephalography showed no periodic synchronous discharges. Cerebrospinal fluid examination on the sixth hospital day revealed tau and 14-3-3 protein with a positive result of real-time quaking-induced conversion. She thereafter developed myoclonus and akinetic mutism and died. Autopsy revealed thinning and spongiform change of the cerebral cortex of the right occipital lobe. Immunostaining showed synaptic-type deposits of abnormal PrP and hypertrophic astrocytes. Consequently, she was diagnosed with the Heidenhain variant of sCJD with both methionine/methionine type 1 and type 2 cortical form based on the western blot of cerebral tissue and PrP gene codon 129 polymorphism.

CONCLUSIONS: When a patient presents with various progressive visual symptoms, even without typical findings of electroencephalography or cranial magnetic resonance imaging, it is essential to suspect the Heidenhain variant of sCJD and perform appropriate cerebrospinal fluid tests.

Keywords: Autopsy, Cerebrospinal Fluid, Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, Heidenhain Variant, Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, Sporadic, Female, Humans, Aged, Creutzfeldt-Jakob Syndrome, Myoclonus, akinetic mutism, Brain

Background

Prion diseases are rapidly progressive and eventually fatal neurodegenerative disorders caused by accumulation of the transmissible scrapie form of the prion protein (PrPSc) following change of the normal cellular form of the prion protein (PrP) to PrPSc in the central nervous system [1]. Prion diseases are classified into 3 types: hereditary types caused by mutations in the PrP gene (

We herein report an autopsy case of the Heidenhain variant of sCJD with both MM type 1 and MM type 2 cortical forms in a patient who developed a variety of visual symptoms at onset, progressing to akinetic mutism and eventually death 4 months later. We were able to examine tau protein, 14-3-3 protein, and RTQuIC in the CSF while the patient was still alive, leading to the correct diagnosis after death despite the absence of periodic synchronous discharges (PSD) on electroencephalography or pathognomonic findings on cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Case Report

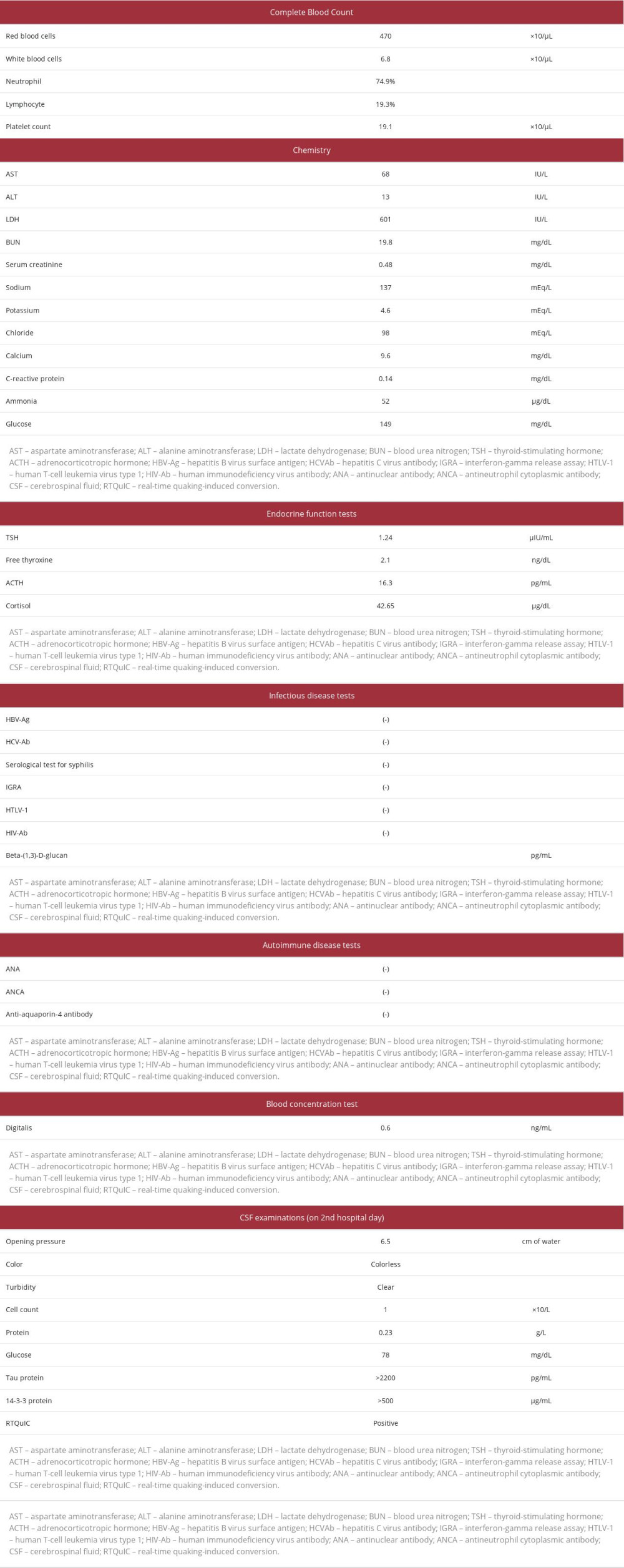

A 72-year-old woman who had no history of transplantation of the dura mater or cornea and who had enough independence in her activities of daily living to drive a car without glasses presented with a 3-month history of photophobia and blurring vision in both eyes. Visual acuity tests performed by her local ophthalmologist had revealed mild cataract and deterioration of unaided vision to 20/63 in the right eye and 20/32 in the left eye. One month later, she developed diplopia, left homonymous hemianopia, and restricted downward movement of her left eye. However, her pupillary light reflex and the findings of ophthalmoscopy and optical coherence tomography angiography were normal. Her visual acuity continued to deteriorate to 20/100 in both eyes 2 months later and 20/2000 at 7 days before admission. She was no longer able to drive a car and required assistance even when transferring to and from a chair, standing up, or maintaining the standing position. Because she also exhibited disorientation with respect to time and place, impairment of word repetition, and difficulty performing simple calculation, she was admitted to our hospital. On admission, her body temperature was 37.1ºC, blood pressure was 159/89 mmHg, pulse rate was 108 beats/min, respiratory rate was 28 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation was 94% on room air. She was emaciated with a body weight of 32.4 kg and body mass index of 14.4 kg/m2. Neurological examination revealed cervical dystonia that caused her neck to remain bent backward, rigidity of the cervical muscles, and deep-tendon hyperreflexia in her right upper and lower extremities with flexor plantar response on toe examination; she had no paralysis or rigidity of her 4 extremities. The sizes of both pupils (3 mm) were normal, and the light reflexes were intact. Her visual acuity and eye movements could not be evaluated because of her disturbance of consciousness. Laboratory findings on admission are presented in Table 1. Only aspar-tate aminotransferase concentration and lactate dehydrogenase concentration were elevated. There were no findings indicating the presence of syphilis or other infectious diseases, autoimmune diseases, or abnormal endocrine functions including thyroid or adrenocortical function.

Because of the patient’s rapidly progressive cognitive dysfunction and deterioration of activities of daily living, sCJD was suspected. Cranial MRI (MAGNETOM 1.5T Avanto Fit; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) on admission, 3 months after onset, using a fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence and diffusion-weighted imaging showed no abnormality (Figure 1). Electroencephalography (NIHON KODEN, Tokyo, Japan) on the second hospital day showed generalized slow waves without PSD, consisting mainly of delta waves (Figure 2). CSF examinations on the second and sixth hospital days showed a normal cell count, protein concentration, and CSF/plasma glucose ratio (Table 1). Residual CSF taken on the sixth hospital day was sent to the laboratory of Nagasaki University, Nagasaki, Japan, for examination of tau protein, 14-3-3 protein, and RTQuIC. Cheyne-Stokes respiration and decorticate rigidity were observed 2 weeks after admission, followed by myoclonus 3 weeks after admission. The patient then rapidly developed akinetic mutism and died 4 weeks after admission (4 months after onset). After her death, the CSF analysis revealed the presence of tau protein and 14-3-3 protein and a positive result of RTQuIC. According to these findings and the clinical symptoms, including a variety of visual symptoms at the onset with rapidly progressive cognitive dysfunction, the probable diagnosis was determined to be the Heidenhain variant of sCJD. A pathological autopsy revealed a brain weight of 1400 g (Figure 3A), enlarged cerebral sulci in the bilateral frontal lobes, and focal atrophy and thinning of the cerebral cortex at the medial basal aspect in the right occipital lobe (Figure 3B). Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the medial basal aspect of the right occipital lobe revealed spongiform changes of the cortex, neuronal loss, and neuropil rarefaction (Figure 4A). Furthermore, in the same area, immunostaining for PrP with 3F4 antibody showed diffuse synaptic-type deposits of abnormal PrP (Figure 4B), and immunohistochemical staining for glial fibrillary acidic protein showed hypertrophic astrocytes (Figure 4C). However, these findings were unclear in the putamen and thalamus. The

Discussion

Pathological findings obtained by brain biopsy or brain autopsy are usually required for a definitive diagnosis of prion diseases, including sCJD [11]. Therefore, pathological examiners must take appropriate preventive measures to avoid infection by PrPSc by recognizing the possibility of sCJD before performing such examinations [12]. Electroencephalography and cranial MRI can be helpful to suspect or diagnose sCJD without brain biopsy or autopsy [13]. The presence of PSD on electroencephalography is a representative finding observed in 67% to 94% of patients with sCJD [14–16]. It is also observed in 77.8% of patients with the Heidenhain variant of sCJD [9]. As for the phenotype of sCJD, such typical findings on electroencephalography are reportedly much more common in patients with MM1 than in those with MM2-costal, MM2-thalamic, MV2, and VV2 subtypes [4,17]. Furthermore, the sensitivity and specificity of cranial MRI for the diagnosis of sCJD are reportedly 92.3% and 93.8%, respectively [18]. Hyperintensity of the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, and thalamus on diffusion-weighted imaging and FLAIR sequences is pathognomonic for sCJD, which can be observed in patients with all sub-types except the MM2-thalamic subtype [4,19]. In addition, a study showed that 55.5% of patients with the Heidenhain variant of sCJD had brain atrophy and white matter degeneration in the occipital lobe, parietal lobe, and basal ganglia [9]. However, only 70% of patients with the Heidenhain variant of sCJD show the typical findings on cranial MRI [9]. Our patient with the Heidenhain variant of sCJD developed a variety of visual symptoms consisting mainly of deterioration of visual acuity without any abnormal findings of her eyeballs, followed by rapidly progressive cognitive dysfunction, consciousness disturbance, akinetic mutism, and eventual death 4 months after onset. Diagnosis of the Heidenhain variant of sCJD was challenging while she was alive because of her rapidly progressive clinical course and the lack of characteristic findings of electroencephalography, especially PSD, or typical findings on cranial MRI, even in the presence of characteristic symptoms of sCJD (including progressive cognitive dysfunction, myoclonus, and akinetic mutism) [1,8]. The lack of typical findings on electroencephalography and cranial MRI in this case may have been because the sCJD was of the Heidenhain variant containing the MM2-constal form.

It is essential to perform examinations for tau protein, 14-3-3 protein, and RTQuIC in the CSF at the earliest stage possible to diagnose the Heidenhain variant of sCJD, especially in a patient with normal electroencephalography or cranial MRI findings, as in the present case. Various positive and negative predictive values for sCJD of 14-3-3 protein in the CSF were reported; 31% and <10%, 35% and 99%, 69% and 88%, 72% and 86%, 76% and 97%, 81% and 68%, 87% and 88%, 87% and 94%, 92% and 98%, and 96% and 76%, respectively [20]. In a study, tau protein and 14-3-3 protein in the CSF were detected in 45.5% and 55.5% of patients with the Heidenhain variant of sCJD, respectively [9]. The World Health Organization diagnostic criteria also indicated that the detection of 14-3-3 protein in CSF at less than 2 years from onset indicates “probable” sCJD [11]. Furthermore, RTQuIC detects abnormal PrP in CSF with a sensitivity of >70% [21]. However, the rapidly progressive clinical course may make it impossible to perform such tests in a timely manner [21]. To avoid failing to perform them at an appropriate time, it is important to know the typical symptoms of the Heidenhain variant of sCJD and suspect it at an earlier stage. The main features of the Heidenhain variant of sCJD are a variety of rapidly progressive visual symptoms as follows: deterioration of visual acuity (27.8–36.4%), blurring vision (27.3–38.9%), and restricted vision (4.5–38.9%) [9,10]. Our patient initially developed photophobia and blurring vision 3 months before admission, followed by diplopia and homonymous hemianopia 1 month later; she eventually presented with visual activity of light perception on admission. The clues to the diagnosis of probable Heidenhain variant of sCJD in this case were the detection of tau protein and 14-3-3 protein and the positive RTQuIC in the CSF examination performed on the sixth hospital day. Knowing these results while the patient is alive could help medical personnel to explain the significance of a definitive diagnosis by autopsy to the patient’s family and avoid the serious risk of becoming infected.

In addition to the above-mentioned visual symptoms, RPD is a major symptom of the Heidenhain variant of sCJD. RPD is mainly caused by central nervous system infections, auto-immune encephalitis or encephalopathy, neurodegenerative disorders, malignant tumors, and cerebrovascular disease; a much less common cause is prion diseases [19]. Prompt diagnosis and treatment of RPD are mandatory because causative diseases can be treatable, and they can be serious public health threats due to their infectivity [22]. While most RPDs commonly progress within 1 or 2 years, RPD due to prion diseases can progress more rapidly, even within several days or weeks [1,22]. Among 22 autopsy cases of patients who presented with RPD and died within 4 years, the largest number of cases [8 (36.3%)] were caused by sCJD. The survival period of those 8 patients was about 1 year, which was shorter than that of the remaining 14 patients with RPD of other causes [23]. Recently, a three-step diagnostic procedure for RPD has also been reported: patient history and clinical examination; standard technical procedures (blood tests, imaging such as CT or MRI, CSF, and electroencephalography); and advanced diagnostics (biomaterials, imaging such as positron emission tomography examination, anti-inflammatory therapy, and brain or leptomeningeal biopsy) [22]. In a patient with rare presentations of an uncommon disease, such as in the present case, the procedure may be useful to rule out other more common diseases. Our patient presented with cognitive dys-function 7 days before admission and died 1 month after admission. This extremely rapid progressive cognitive dysfunction is a useful sign suggesting a possible diagnosis of prion diseases such as sCJD.

Conclusions

When a patient presents with various rapidly progressive visual symptoms, it is essential to suspect the Heidenhain variant of sCJD and examine tau protein, 14-3-3 protein, and RTQuIC in the CSF as soon as possible, even without typical findings on electroencephalography or cranial MRI.

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Laboratory data.

References:

1.. Johnson RT, Gibbs CJ, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and related transmissible spongiform encephalopathies: N Engl J Med, 1998; 339(27); 1994-2004

2.. Uttley L, Carroll C, Wong R, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: A systematic review of global incidence, prevalence, infectivity, and incubation: Lancet Infect Dis, 2020; 20(1); e2-e10

3.. Abrahantes JC, Aerts M, van Everbroeck B, Classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease based on clinical and neuropathological characteristics: Eur J Epidemiol, 2007; 22(7); 457-65

4.. Nozaki I, Hamaguchi T, Sanjo N, Prospective 10-year surveillance of human prion diseases in Japan: Brain, 2010; 133(10); 3043-57

5.. Watson N, Brandel JP, Green A, The importance of ongoing international surveillance for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: Nat Rev Neurol, 2021; 17(6); 362-79

6.. Parchi P, Giese A, Capellari S, Classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease based on molecular and phenotypic analysis of 300 subjects: Ann Neurol, 1999; 46; 224-33

7.. Sanjo N, Mizusawa H, Prion disease-The characteristics and diagnostic points in Japan: Clin Neurol, 2010; 50; 287-300

8.. Kropp S, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ, Finkenstaedt M, The Heidenhain variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: Arch Neurol, 1999; 56(1); 55-61

9.. Baiardi S, Capellari S, Ladogana A, Revisiting the Heidenhain variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: Evidence for prion type variability influencing clinical course and laboratory findings: J Alzheimers Dis, 2016; 50(2); 465-76

10.. Cooper SA, Isolated visual symptoms at onset in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: The clinical phenotype of the “Heidenhain variant”: Br J Ophthalmol, 2005; 89(10); 1341-47

11.. : Global surveillance, diagnosis and therapy of human Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies: Report of a WHO consultation, 1998, WHO

12.. Lenk J, Engellandt K, Terai N, Rapid progressive visual decline and visual field defects in two patients with the Heidenhain variant of Creutzfeld-Jakob disease: J Clin Neurosci, 2018; 50; 135-39

13.. Hermann P, Appleby B, Brandel J-P, Biomarkers and diagnostic guidelines for sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: Lancet Neurol, 2021; 20(3); 235-46

14.. Steinhoff BJ, Räcker S, Herrendorf G, Accuracy and reliability of periodic sharp wave complexes in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: Arch Neurol, 1996; 53(2); 162-66

15.. Nakatani E, Kanatani Y, Kaneda H, Specific clinical signs and symptoms are predictive of clinical course in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: Eur J Neurol, 2016; 23(9); 1455-62

16.. Aoki T, Kobayashi K, Jibiki I, An autopsied case of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease with the lateral geniculate body lesion showing antagonizing correlation between periodic synchronous discharges and photically induced giant evoked responses: Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 1998; 52(3); 333-37

17.. Collins SJ, Sanchez-Juan P, Masters CL, Determinants of diagnostic investigation sensitivities across the clinical spectrum of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: Brain, 2006; 129(Pt 9); 2278-87

18.. Shiga Y, Miyazawa K, Sato S, Diffusion-weighted MRI abnormalities as an early diagnostic marker for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: Neurology, 2004; 63(3); 443-49

19.. Ginsberg SD, Anuja P, Venugopalan V, Rapidly progressive dementia: An eight year (2008–2016) retrospective study: PLoS One, 2018; 13(1); e0189832

20.. Behaeghe O, Mangelschots E, De Vil B, Cras P, A systematic review comparing the diagnostic value of 14-3-3 protein in the cerebrospinal fluid, RTQuIC and RT-QuIC on nasal brushing in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: Acta Neurol Belg, 2018; 118(3); 395-403

21.. Sano K, Satoh K, Atarashi R, Early detection of abnormal prion protein in genetic human prion diseases now possible using real-time QUIC assay: PLoS One, 2013; 8(1); e54915

22.. Hermann P, Zerr I, Rapidly progressive dementias – aetiologies, diagnosis and management: Nat Rev Neurol, 2022; 18(6); 363-76

23.. Josephs KA, Ahlskog JE, Parisi JE, Rapidly progressive neurodegenerative dementias: Arch Neurol, 2009; 66(2); 201-7

Figures

In Press

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942770

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943214

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943010

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943687

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250